The Rise and Possible Demise of Afrikaans As a Public Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prioritizing African Languages: Challenges to Macro-Level Planning for Resourcing and Capacity Building

Prioritizing African Languages: Challenges to macro-level planning for resourcing and capacity building Tristan M. Purvis Christopher R. Green Gregory K. Iverson University of Maryland Center for Advanced Study of Language Abstract This paper addresses key considerations and challenges involved in the process of prioritizing languages in an area of high linguistic di- versity like Africa alongside other world regions. The paper identifies general considerations that must be taken into account in this process and reviews the placement of African languages on priority lists over the years and across different agencies and organizations. An outline of factors is presented that is used when organizing resources and planning research on African languages that categorizes major or crit- ical languages within a framework that allows for broad coverage of the full linguistic diversity of the continent. Keywords: language prioritization, African languages, capacity building, language diversity, language documentation When building language capacity on an individual or localized level, the question of which languages matter most is relatively less complicated than it is for those planning and providing for language capabilities at the macro level. An American anthropology student working with Sierra Leonean refugees in Forecariah, Guinea, for ex- ample, will likely know how to address and balance needs for lan- guage skills in French, Susu, Krio, and a set of other languages such as Temne and Mandinka. An education official or activist in Mwanza, Tanzania, will be concerned primarily with English, Swahili, and Su- kuma. An administrator of a grant program for Less Commonly Taught Languages, or LCTLs, or a newly appointed language authori- ty for the United States Department of Education, Department of Commerce, or U.S. -

Corpus Collection for Under-Resourced Languages with More Than One Million Speakers

Corpus collection for under-resourced languages with more than one million speakers Dirk Goldhahn1, Maciej Sumalvico1, Uwe Quasthoff1,2 Natural Language Processing Group, University of Leipzig, Germany Department of African Languages, University of South Africa, South Africa Email: { dgoldhahn, janicki, quasthoff, }@informatik.uni-leipzig.de Abstract For only 40 of about 350 languages with more than one million speakers, the situation concerning text resources is comfortable. For the remaining languages, the number of speakers indicates a need for both corpora and tools. This paper describes a corpus collection initiative for these languages. While random Web crawling has serious limitations, native speakers with knowledge of web pages in their language are of invaluable help. The aim is to give interested scholars, language enthusiasts the possibility to contribute to corpus creation or extension by simply entering a URL into the Web Interface. Using a Web portal URLs of interest are collected with the help of the respective communities. A standardized corpus processing chain for daily newspaper corpora creation is adapted to append newly added web pages to an increasing corpus. As a result we will be able to collect larger corpora for under-resourced languages by a community effort. These corpora will be made publicly available. Keywords: corpora, under-resourced languages, Web portal, community 1. Introduction links require the execution of JavaScript code by the There are about 350 languages with more than one million crawler which often produces errors. So, if a website speakers1. For about 40 of them, the situation concerning heavily uses JavaScript links and there are no other links text resources is comfortable: there are corpora of pointing to special pages (coming from another website, reasonable size and also tools like POS taggers adapted to for instance), then all but the main page might be these languages. -

Old Frisian, an Introduction To

An Introduction to Old Frisian An Introduction to Old Frisian History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. University of Leiden John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 American National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bremmer, Rolf H. (Rolf Hendrik), 1950- An introduction to Old Frisian : history, grammar, reader, glossary / Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Frisian language--To 1500--Grammar. 2. Frisian language--To 1500--History. 3. Frisian language--To 1550--Texts. I. Title. PF1421.B74 2009 439’.2--dc22 2008045390 isbn 978 90 272 3255 7 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 3256 4 (Pb; alk. paper) © 2009 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P.O. Box 36224 · 1020 me Amsterdam · The Netherlands John Benjamins North America · P.O. Box 27519 · Philadelphia pa 19118-0519 · usa Table of contents Preface ix chapter i History: The when, where and what of Old Frisian 1 The Frisians. A short history (§§1–8); Texts and manuscripts (§§9–14); Language (§§15–18); The scope of Old Frisian studies (§§19–21) chapter ii Phonology: The sounds of Old Frisian 21 A. Introductory remarks (§§22–27): Spelling and pronunciation (§§22–23); Axioms and method (§§24–25); West Germanic vowel inventory (§26); A common West Germanic sound-change: gemination (§27) B. -

Afrikaans FAMILY HISTORY LIBRARY" SALTLAKECITY, UTAH TMECHURCHOF JESUS CHRISTOF Latl'er-Qt.Y SAINTS

GENEALOGICAL WORD LIST ~ Afrikaans FAMILY HISTORY LIBRARY" SALTLAKECITY, UTAH TMECHURCHOF JESUS CHRISTOF LATl'ER-Qt.y SAINTS This list contains Afrikaans words with their English these compound words are included in this list. You translations. The words included here are those that will need to look up each part of the word separately. you are likely to find in genealogical sources. If the For example, Geboortedag is a combination of two word you are looking for is not on this list, please words, Geboorte (birth) and Dag (day). consult a Afrikaans-English dictionary. (See the "Additional Resources" section below.) Alphabetical Order Afrikaans is a Germanic language derived from Written Afrikaans uses a basic English alphabet several European languages, primarily Dutch. Many order. Most Afrikaans dictionaries and indexes as of the words resemble Dutch, Flemish, and German well as the Family History Library Catalog..... use the words. Consequently, the German Genealogical following alphabetical order: Word List (34067) and Dutch Genealogical Word List (31030) may also be useful to you. Some a b c* d e f g h i j k l m n Afrikaans records contain Latin words. See the opqrstuvwxyz Latin Genealogical Word List (34077). *The letter c was used in place-names and personal Afrikaans is spoken in South Africa and Namibia and names but not in general Afrikaans words until 1985. by many families who live in other countries in eastern and southern Africa, especially in Zimbabwe. Most The letters e, e, and 0 are also used in some early South African records are written in Dutch, while Afrikaans words. -

The Pronunciation of English in South Africa by L.W

The Pronunciation of English in South Africa by L.W. Lanham, Professor Emeritus, Rhodes University, 1996 Introduction There is no one, typical South African English accent as there is one overall Australian English accent. The variety of accents within the society is in part a consequence of the varied regional origins of groups of native English speakers who came to Africa at different times, and in part a consequence of the variety of mother tongues of the different ethnic groups who today use English so extensively that they must be included in the English-using community. The first truly African, native English accent in South Africa evolved in the speech of the children of the 1820 Settlers who came to the Eastern Cape with parents who spoke many English dialects. The pronunciation features which survive are mainly those from south-east England with distinct Cockney associations. The variables (distinctive features of pronunciation) listed under A below may be attributed to this origin. Under B are listed variables of probable Dutch origin reflecting close association and intermarriage with Dutch inhabitants of the Cape. There was much contact with Xhosa people in that area, but the effect of this was almost entirely confined to the vocabulary. (The English which evolved in the Eastern and Central Cape we refer to as Cape English.) The next large settlement from Britain took place in Natal between 1848 and 1862 giving rise to pronunciation variables pointing more to the Midlands and north of England (List C). The Natal settlers had a strong desire to remain English in every aspect of identity, social life, and behaviour. -

The Importance of Afrikaans

NOT FOR PUBLICATION INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS .JCB-I September 10, 1961 irst Impressions The Importance 29 Bay View Avenue of Afrikaans Tamboer's Kloof Cape Town, South Africa Mr. Richard Nolte Xnstltute of Current 11orld Affairs 366 Madison Avenue New York 17, New York Dear r. Nolte: I hadn't realized, when I was busy wth Afrikaans records n Vrginia, just how important the language s to an understanding of the Republic of South Africa. Many people, here as well as in the States, have assured me that I needn't bother learning the language. ost afrlkaaners speak at least some English, and it is possible to llve quite comfortably without knowing a word of Afrikaans. It is spoken by a decidedly small portion of the world s population. Outside of a few ex-patrlots now living in the Rhodesias and East Afrlca I would meet very few Afrikaans-speaking people outside the Republic. Learning the language would seem at best to be a courtesy. Today, however, the unt-lngual person n South Africa is mssn the very heart-beat of the country. uch of the lfe of white South Africa Is rooted n the Afrikaans language. It S not a dying language, but very much allve and growing. It is the language of the Coloured as well as the majority of Europeans. With incomvlete knowledge of Afrikaans, I must get my news solely from the ]nglsh Press which s often qute dfferent in Interpretation from its counterpart in the Afrlkaans Press. The recent and much discussed books, Die _Eers_te_Steen, by Adam Small, and ,--by ..G. -

Supported Languages in Déjà Vu X3 Afrikaans Catalan Albanian Central

Supported Languages in Déjà Vu X3 Afrikaans Catalan Albanian Central Kurdish Alsatian Cherokee Amharic Chinese (Hong Kong S.A.R.) Arabic (Algeria) Chinese (Macao S.A.R.) Arabic (Bahrain) Chinese (PRC) Arabic (Egypt) Chinese (Singapore) Arabic (Iraq) Chinese (Taiwan) Arabic (Jordan) Corsican Arabic (Kuwait) Croatian Arabic (Lebanon) Czech Arabic (Libya) Danish Arabic (Morocco) Dari Arabic (Oman) Divehi Arabic (Qatar) Dutch Arabic (Saudi Arabia) Dutch (Belgium) Arabic (Syria) Dzongkha (Bhutan) Arabic (Tunisia) Edo Arabic (U.A.E.) English (Australia) Arabic (Yemen) English (Belize) Armenian English (Canada) Assamese English (Caribbean) Azerbaijani (Cyrillic) English (Hong Kong S.A.R.) Azerbaijani (Latin) English (India) Bangla (Bangladesh) English (Indonesia) Bangla (India) English (Ireland) Bashkir English (Jamaica) Basque English (Malasia) Belarusian English (New Zealand) Bosnian (Cyrillic, Bosnia and Herzegovina) English (Philippines) Bosnian (Latin, Bosnia and Herzegovina) English (Singapore) Breton English (South Africa) Bulgarian English (Trinidad and Tobago) Supported Languages in Déjà Vu X3 English (Unites States) Hausa English (Zimbabwe) Hawaiian Estonian Hebrew Faroese Hindi Filipino Hungarian Finnish Ibibio French Icelandic French (Belgium) Igbo French (Cameron) Indonesian French (Canada) Inuktitut (Latin) French (Congo (DRC)) Inuktitut (Syllabics) French (Cote d'Ivoire) Irish French (Haiti) Italian French (Luxembourg) Italian (Switzerland) French (Mali) Japanese French (Monaco) Kannada French (Morocco) Kanuri French (North Africa) -

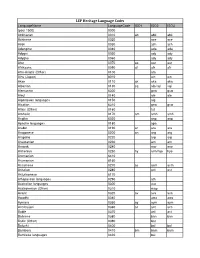

LEP Heritage Language Codes

LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 (post 1500) 0000 Abkhazian 0010 ab abk abk Achinese 0020 ace ace Acoli 0030 ach ach Adangme 0040 ada ada Adygei 0050 ady ady Adyghe 0060 ady ady Afar 0070 aa aar aar Afrikaans 0090 af afr afr Afro-Asiatic (Other) 0100 afa Ainu (Japan) 6010 ain ain Akan 0110 ak aka aka Albanian 0130 sq alb/sqi sqi Alemannic 6300 gsw gsw Aleut 0140 ale ale Algonquian languages 0150 alg Alsatian 6310 gsw gsw Altaic (Other) 0160 tut Amharic 0170 am amh amh Angika 6020 anp anp Apache languages 0180 apa Arabic 0190 ar ara ara Aragonese 0200 an arg arg Arapaho 0220 arp arp Araucanian 0230 arn arn Arawak 0240 arw arw Armenian 0250 hy arm/hye hye Aromanian 6410 Arumanian 6160 Assamese 0270 as asm asm Asturian 0280 ast ast Asturleonese 6170 Athapascan languages 0290 ath Australian languages 0300 aus Austronesian (Other) 0310 map Avaric 0320 av ava ava Awadhi 0340 awa awa Aymara 0350 ay aym aym Azerbaijani 0360 az aze aze Bable 0370 ast ast Balinese 0380 ban ban Baltic (Other) 0390 bat Baluchi 0400 bal bal Bambara 0410 bm bam bam Bamileke languages 0420 bai LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 Banda 0430 bad Bantu (Other) 0440 bnt Basa 0450 bas bas Bashkir 0460 ba bak bak Basque 0470 eu baq/eus eus Batak (Indonesia) 0480 btk Bedawiyet 6180 bej bej Beja 0490 bej bej Belarusian 0500 be bel bel Bemba 0510 bem bem Bengali; ben 0520 bn ben ben Berber (Other) 0530 ber Bhojpuri 0540 bho bho Bihari 0550 bh bih Bikol 0560 bik bik Bilin 0570 byn byn Bini 0580 bin bin Bislama -

Language Shift from Afrikaans to English in “Coloured” Families in Port Elizabeth: Three Case Studies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository LANGUAGE SHIFT FROM AFRIKAANS TO ENGLISH IN “COLOURED” FAMILIES IN PORT ELIZABETH: THREE CASE STUDIES Esterline Fortuin 15221148 Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Intercultural Communication at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Frenette Southwood December 2009 Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained herein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof and that I have not previously, in its entirety or in part, submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 31 August 2009 Copyright © 2009 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Abstract This thesis investigates whether language shift is occurring within the community of the northern areas of Port Elizabeth. These areas are historically predominantly “coloured” and Afrikaans-speaking, and are mixed in terms of the socioeconomic status of their inhabitants. Lately, there is a tendency for many of the younger generation to speak more English. Using the model of another study (Anthonissen and George 2003) done in the Cape Town area, three generations (grandparent, parent and grandchild) of three families were interviewed regarding their use of English and Afrikaans in various domains. The pattern of language shift in this study differs somewhat, but not totally, from that described in Anthonissen and George (2003) and Farmer (2009). In these two studies, there was a shift from predominantly Afrikaans in the older two generations to English in the youngest generation. -

Dutch. a Linguistic History of Holland and Belgium

Dutch. A linguistic history of Holland and Belgium Bruce Donaldson bron Bruce Donaldson, Dutch. A linguistic history of Holland and Belgium. Uitgeverij Martinus Nijhoff, Leiden 1983 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/dona001dutc02_01/colofon.php © 2013 dbnl / Bruce Donaldson II To my mother Bruce Donaldson, Dutch. A linguistic history of Holland and Belgium VII Preface There has long been a need for a book in English about the Dutch language that presents important, interesting information in a form accessible even to those who know no Dutch and have no immediate intention of learning it. The need for such a book became all the more obvious to me, when, once employed in a position that entailed the dissemination of Dutch language and culture in an Anglo-Saxon society, I was continually amazed by the ignorance that prevails with regard to the Dutch language, even among colleagues involved in the teaching of other European languages. How often does one hear that Dutch is a dialect of German, or that Flemish and Dutch are closely related (but presumably separate) languages? To my knowledge there has never been a book in English that sets out to clarify such matters and to present other relevant issues to the general and studying public.1. Holland's contributions to European and world history, to art, to shipbuilding, hydraulic engineering, bulb growing and cheese manufacture for example, are all aspects of Dutch culture which have attracted the interest of other nations, and consequently there are numerous books in English and other languages on these subjects. But the language of the people that achieved so much in all those fields has been almost completely neglected by other nations, and to a degree even by the Dutch themselves who have long been admired for their polyglot talents but whose lack of interest in their own language seems never to have disturbed them. -

Afrikaans and Dutch As Closely-Related Languages: a Comparison to West Germanic Languages and Dutch Dialects

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus, Vol. 47, 2015, 1-18 doi: 10.5842/47-0-649 Afrikaans and Dutch as closely-related languages: A comparison to West Germanic languages and Dutch dialects Wilbert Heeringa Institut für Germanistik, Fakultät III – Sprach- und Kulturwissenschaften, Carl von Ossietzky Universität, Oldenburg, Germany Email: [email protected] Febe de Wet Human Language Technology Research Group, CSIR Meraka Institute, Pretoria, South Africa | Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Stellenbosch University, South Africa Email: [email protected] Gerhard B. van Huyssteen Centre for Text Technology (CTexT), North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa Email: [email protected] Abstract Following Den Besten‟s (2009) desiderata for historical linguistics of Afrikaans, this article aims to contribute some modern evidence to the debate regarding the founding dialects of Afrikaans. From an applied perspective (i.e. human language technology), we aim to determine which West Germanic language(s) and/or dialect(s) would be best suited for the purposes of recycling speech resources for the benefit of developing speech technologies for Afrikaans. Being recognised as a West Germanic language, Afrikaans is first compared to Standard Dutch, Standard Frisian and Standard German. Pronunciation distances are measured by means of Levenshtein distances. Afrikaans is found to be closest to Standard Dutch. Secondly, Afrikaans is compared to 361 Dutch dialectal varieties in the Netherlands and North-Belgium, using material from the Reeks Nederlandse Dialectatlassen, a series of dialect atlases compiled by Blancquaert and Pée in the period 1925-1982 which cover the Dutch dialect area. Afrikaans is found to be closest to the South-Holland dialectal variety of Zoetermeer; this largely agrees with the findings of Kloeke (1950). -

Theories About the Origin of Afrikaans

Hofmeyr Foundation Lectures I THEORIES ABOUT THE ORIGIN OF AFRIKAANS Professor J. J. Smith JOHANNESBURG WITWATERSRAND UNIVERSITY PRESS A 439.3609 5MI NOTE When Professor].]. Smith deliz•ered this lecture, on(y parts of it had been JJ'ritten out in full, and at the time of hi.r death he had not been able to complete the manuscript. I I has been prepared for publication by members of his fami(y, and a member of the audience. Thry cannot claim ab1•qys to present the zmy u•ords spoken in]ohannesbm;f!,, but, U'orkingfrom his notes and recollections of the lecture, they hare tried to reproduce it as exact(y a.r possible. THEORIES ABOUT THE ORIGTK OF AFRIKAANS e all know that there is a great diversity of language in the Wworld. Here in South Africa we are every day reminded of this fact when we hear around us not only English and Afrikaans, but also several varieties of Bantu. We continually hear people jabbering away in tongues which are often to us mere volumes of sound. But it is not only the different languages belonging to different peoples that strike us; even one and the same language becomes a regu lar Proteus as soon as we try to view it at all closely. The English of Britain is certainly very like the English of America; but whoever believes that the two are identical must indeed be very unobservant. Again, each social group speaks its own language, which differs from that of another social group, though both groups believe themselves to be speaking the same language.