Language Shift from Afrikaans to English in “Coloured” Families in Port Elizabeth: Three Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

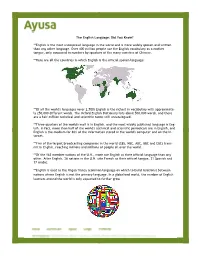

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

Prioritizing African Languages: Challenges to Macro-Level Planning for Resourcing and Capacity Building

Prioritizing African Languages: Challenges to macro-level planning for resourcing and capacity building Tristan M. Purvis Christopher R. Green Gregory K. Iverson University of Maryland Center for Advanced Study of Language Abstract This paper addresses key considerations and challenges involved in the process of prioritizing languages in an area of high linguistic di- versity like Africa alongside other world regions. The paper identifies general considerations that must be taken into account in this process and reviews the placement of African languages on priority lists over the years and across different agencies and organizations. An outline of factors is presented that is used when organizing resources and planning research on African languages that categorizes major or crit- ical languages within a framework that allows for broad coverage of the full linguistic diversity of the continent. Keywords: language prioritization, African languages, capacity building, language diversity, language documentation When building language capacity on an individual or localized level, the question of which languages matter most is relatively less complicated than it is for those planning and providing for language capabilities at the macro level. An American anthropology student working with Sierra Leonean refugees in Forecariah, Guinea, for ex- ample, will likely know how to address and balance needs for lan- guage skills in French, Susu, Krio, and a set of other languages such as Temne and Mandinka. An education official or activist in Mwanza, Tanzania, will be concerned primarily with English, Swahili, and Su- kuma. An administrator of a grant program for Less Commonly Taught Languages, or LCTLs, or a newly appointed language authori- ty for the United States Department of Education, Department of Commerce, or U.S. -

The Best Interests of the Child Are of Paramount

WHERE TO FIND THE FAMILY ADVOCATE IN YOUR AREA: ISSUED 2018 ENGLISH National Office Sibasa Mthatha Adv. C.J Maree Northern Cape George Adv. Petunia Seabi-Mathope Adv. R.D. Ramanenzhe Adv. M.S. Van Pletzen (Senior Family Advocate) Kimberley – Provincial Office Adv. J. Gerber Chief Family Advocate (Family Advocate) (Senior Family Advocate) Tel: 012 323 0760, Fax: 012 323 9566 Adv. P.M Molokwane (Senior Family Advocate) Ms C. Molai (Secretary to the Chief Tel: 015 960 1410 Tel: 047 532 3998, Pretoria [email protected] (Acting Principal Family Advocate) Tel: 044 802 4200, Family Advocate) [email protected] Fax: 047 532 5337 Postal Address: Private Bag X 88, (Senior Family Advocate) Fax: 044 802 4202 OFFICE OF THE FAMILY ADVOCATE Tel: 012 357 8022 Postal Address: Private Bag X 5005 [email protected] Pretoria, 0001. Tel: 053 833 1019/63, [email protected] Fax: 012 357 8043 Thohoyandou 0950. Physical Address: Postal Address: Private Bag X 5255 Physical Address: 4th Floor, Centre Fax: 053 833 1062/69 Postal Address: Private Bag X 6586, [email protected] Thohoyandou Magistrate Court Mthatha 5099. Physical Address: 6th Walk Building, C/o Thabo Sehume [email protected] George, 6530. Physical Address: Postal Address: Private Bag X 6071, THE BEST INTERESTS Postal Address: Private Bag X 81 Floor, Manpower Building, C/o & Pretorius Streets , Pretoria, 0001 Cnr Cradock & Cathedral Street, Pretoria 0001. Physical Address: Mpumalanga Elliot and Madeira Street, Kimberley, 8300. Physical Address: Bateleur Park Building, George, 329 Pretorius Street, Momentum Nelspruit – Provincial Office Mthatha, 5100 Soshanguve 5th Floor, New Public Building OF THE CHILD ARE Building, West Tower, Pretoria Adv. -

Basic Itinerary for 10 Day Golf Tour: Cape Town – Port Elizabeth

www.freewalker.co.za Facebook: Freewalker Adventure Travel 10 day South African Golf Adventure |Cape Town –Eastern Cape via Garden Route This packaged tour starts in Cape Town (voted one of the best Cities to visit in the World),playing at the highly rated Steenberg Golf & Wine Estate and The Royal Cape, which is Africa’s oldest Club. The Tour continues along the World famous Garden Route to Fancourt Resort & Lifestyle Estate for a leisurely experience. The Pezula Golf Course on the Knysna cliffs is the final destination before heading off into our Big 5 Safari region for an abundance of wildlife experiences in the Eastern Cape, the Adventure Province. Basic itinerary for 10 day golf tour: Cape Town – Port Elizabeth Day 1: Arrival in South Africa Met at Cape Town International Airport by Freewalker Guide Check in at Cape Town accommodation (4 nights) Group drinks, dinner & brief at V&A Waterfront Day 2: Steenberg Golf & Wine Estate Breakfast at accommodation or Golf Club 18 holes on Steenberg Golf Course Lunch & drinks at Club house Wine tasting on Estate/Groot Constantia Estate Dinner on the coast of Kalk Bay Day 3: Sight-seeing around the Cape Peninsula Breakfast at accommodation Table Mountain cable car and viewing from the top Cape Point Nature Reserve visit (Southern-most tip of Africa) Lunch at the Two Oceans Restaurant (overlooking the famous False Bay) Peninsula drive via Chapman’s Peak and Hout Bay Sunset drinks and dinner at the cosmopolitan Camps Bay Day 4: Oldest Golf course in Africa day Breakfast at accommodation or Golf -

South Africa Yearbook 2012/13

SOUTH AFRICA YEARBOOK 2012/13 Land and its p Land and its people Situated at the southern tip of Africa, South Africa boasts an amazing variety of natural beauty and an abundance of wildlife, birds, Land and its p plant species and mineral wealth. In addi- tion, its population comprises a unique diversity of people and cultures. The southern tip of Africa is also where archaeologists discovered 2,5-million-year- old fossils of man’s earliest ancestors, as well as 100 000-year-old remains of modern man. The land Stretching latitudinally from 22°S to 35°S and longitudinally from 17°E to 33°E, South Africa’s surface area covers 1 219 602 km2. According to Census 2011, the shift of the national boundary over the Indian Ocean in the north-east corner of KwaZulu-Natal to cater for the Isimangaliso Wetland Park led to the increase in South Africa’s land area. Physical features range from bushveld, grasslands, forests, deserts and majestic mountain peaks, to wide unspoilt beaches and coastal wetlands. The country shares common bound- aries with Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Swaziland, while the Mountain Kingdom of Lesotho is landlocked by South African territory in the south-east. The 3 000-km shoreline stretching from the Mozambican border in the east to the Namibian border in the west is surrounded by the Atlantic and Indian oceans, which meet at Cape Point in the continent’s south- western corner. Prince Edward and Marion islands, annexed by South Africa in 1947, lie some 1 920 km south-east of Cape Town. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the -

German and English Noun Phrases

RICE UNIVERSITY German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach Ward Keith Barrows A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF 3 1272 00675 0689 Master of Arts Thesis Directors signature: / Houston, Texas April, 1971 Abstract: German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach, by Ward Keith Barrows The paper presents a contrastive approach to German and English based on the theory of transformational grammar. In the first chapter, contrastive analysis is discussed in the context of foreign language teaching. It is indicated that contrastive analysis in pedagogy is directed toward the identification of sources of interference for students of foreign languages. It is also pointed out that some differences between two languages will prove more troublesome to the student than others. The second chapter presents transformational grammar as a theory of language. Basic assumptions and concepts are discussed, among them the central dichotomy of competence vs performance. Chapter three then present the structure of a grammar written in accordance with these assumptions and concepts. The universal base hypothesis is presented and adopted. An innovation is made in the componential structire of a transformational grammar: a lexical component is created, whereas the lexicon has previously been considered as part of the base. Chapter four presents an illustration of how transformational grammars may be used contrastively. After a base is presented for English and German, lexical components and some transformational rules are contrasted. The final chapter returns to contrastive analysis, but discusses it this time from the point of view of linguistic typology in general. -

New Zealand English

New Zealand English Štajner, Renata Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2011 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:005306 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Njemačkog jezika i književnosti Renata Štajner New Zealand English Završni rad Prof. dr. sc. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2011 0 Summary ....................................................................................................................................2 Introduction................................................................................................................................4 1. History and Origin of New Zealand English…………………………………………..5 2. New Zealand English vs. British and American English ………………………….….6 3. New Zealand English vs. Australian English………………………………………….8 4. Distinctive Pronunciation………………………………………………………………9 5. Morphology and Grammar……………………………………………………………11 6. Maori influence……………………………………………………………………….12 6.1.The Maori language……………………………………………………………...12 6.2.Maori Influence on the New Zealand English………………………….………..13 6.3.The -

Corpus Collection for Under-Resourced Languages with More Than One Million Speakers

Corpus collection for under-resourced languages with more than one million speakers Dirk Goldhahn1, Maciej Sumalvico1, Uwe Quasthoff1,2 Natural Language Processing Group, University of Leipzig, Germany Department of African Languages, University of South Africa, South Africa Email: { dgoldhahn, janicki, quasthoff, }@informatik.uni-leipzig.de Abstract For only 40 of about 350 languages with more than one million speakers, the situation concerning text resources is comfortable. For the remaining languages, the number of speakers indicates a need for both corpora and tools. This paper describes a corpus collection initiative for these languages. While random Web crawling has serious limitations, native speakers with knowledge of web pages in their language are of invaluable help. The aim is to give interested scholars, language enthusiasts the possibility to contribute to corpus creation or extension by simply entering a URL into the Web Interface. Using a Web portal URLs of interest are collected with the help of the respective communities. A standardized corpus processing chain for daily newspaper corpora creation is adapted to append newly added web pages to an increasing corpus. As a result we will be able to collect larger corpora for under-resourced languages by a community effort. These corpora will be made publicly available. Keywords: corpora, under-resourced languages, Web portal, community 1. Introduction links require the execution of JavaScript code by the There are about 350 languages with more than one million crawler which often produces errors. So, if a website speakers1. For about 40 of them, the situation concerning heavily uses JavaScript links and there are no other links text resources is comfortable: there are corpora of pointing to special pages (coming from another website, reasonable size and also tools like POS taggers adapted to for instance), then all but the main page might be these languages. -

English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate

ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 First published in 1993 by Rhodes University Grahamstown South Africa ©PROF LS WRIGHT -1993 Laurence Wright English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate ISBN: 0-620-03155-7 No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Mr Vice Chancellor, my former teachers, colleagues, ladies and gentlemen: It is a special privilege to be asked to give an inaugural lecture before the University in which my undergraduate days were spent and which holds, as a result, a special place in my affections. At his own "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" in 1866, Thomas Carlyle observed that "the true University of our days is a Collection of Books".1 This definition - beloved of university library committees worldwide - retains a certain validity even in these days of microfiche and e-mail, but it has never been remotely adequate. John Henry Newman supplied the counterpoise: . no book can convey the special spirit and delicate peculiarities of its subject with that rapidity and certainty which attend on the sympathy of mind with mind, through the eyes, the look, the accent and the manner. -

Old Frisian, an Introduction To

An Introduction to Old Frisian An Introduction to Old Frisian History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. University of Leiden John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 American National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bremmer, Rolf H. (Rolf Hendrik), 1950- An introduction to Old Frisian : history, grammar, reader, glossary / Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Frisian language--To 1500--Grammar. 2. Frisian language--To 1500--History. 3. Frisian language--To 1550--Texts. I. Title. PF1421.B74 2009 439’.2--dc22 2008045390 isbn 978 90 272 3255 7 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 3256 4 (Pb; alk. paper) © 2009 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P.O. Box 36224 · 1020 me Amsterdam · The Netherlands John Benjamins North America · P.O. Box 27519 · Philadelphia pa 19118-0519 · usa Table of contents Preface ix chapter i History: The when, where and what of Old Frisian 1 The Frisians. A short history (§§1–8); Texts and manuscripts (§§9–14); Language (§§15–18); The scope of Old Frisian studies (§§19–21) chapter ii Phonology: The sounds of Old Frisian 21 A. Introductory remarks (§§22–27): Spelling and pronunciation (§§22–23); Axioms and method (§§24–25); West Germanic vowel inventory (§26); A common West Germanic sound-change: gemination (§27) B. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL