Introduction to the History of the English Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

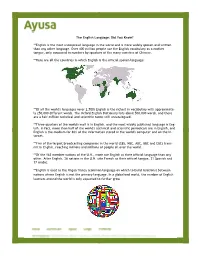

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

Early Modern English

Mrs. Halverson: English 9A Intro to Shakespeare’s Language: Early Modern English Romeo and Juliet was written around 1595, when William Shakespeare was about 31 years old. In Shakespeare's day, England was just barely catching up to the Renaissance that had swept over Europe beginning in the 1400s. But England's theatrical performances soon put the rest of Europe to shame. Everyone went to plays, and often more than once a week. There you were not only entertained but also exposed to an explosion of new phrases and words entering the English language for overseas and from the creative minds of Shakespeare and his contemporaries. The language Shakespeare uses in his plays is known as Early Modern English, and is approximately contemporaneous with the writing of the King James Bible. Believe it or not, much of Shakespeare's vocabulary is still in use today. For instance, Howard Richler in Take My Words noted the following phrases originated with Shakespeare: without rhyme or reason flesh and blood in a pickle with bated breath vanished into thin air budge an inch more sinned against than sinning fair play playing fast and loose brevity is the soul of wit slept a wink foregone conclusion breathing your last dead as a door-nail point your finger the devil incarnate send me packing laughing-stock bid me good riddance sorry sight heart of gold come full circle Nonetheless, Shakespeare does use words or forms of words that have gone out of use. Here are some guidelines: 1) Shakespeare uses some personal pronouns that have become archaic. -

Handout 1: the History of the English Language 1. Proto-Indo-European

Handout 1: The history of the English language Cold climate: they had a word for snow: *sneigwh- (cf. Latin nix, Greek Seminar English Historical Linguistics and Dialectology, Andrew McIntyre niphos, Gothic snaiws, Gaelic sneachta). Words for beech, birch, elm, ash, oak, apple, cherry; bee, bear, beaver, eagle. 1. Proto-Indo-European (roughly 3500-2500 BC) Original location is also deduced from subsequent spread of IE languages. Bronze age technology. They had gold, silver, copper, but not iron. 1.1. Proto-Indo-European and linguistic reconstruction They rode horses and had domesticated sheep, cattle. Cattle a sign of wealth (cf. Most languages in Europe, and others in areas stretching as far as India, are called Indo- fee/German Vieh ‘cattle’, Latin pecunia ‘money’/pecus ‘cattle’) European languages, as they descend from a language called Proto-Indo-European Agriculture: cultivated cereals *gre-no- (>grain, corn), also grinding of corn (PIE). Here ‘proto’ means that there are no surviving texts in the language and thus that *mela- (cf. mill, meal); they also seem to have had ploughs and yokes. linguists reconstructed the language by comparing similarities and systematic differences Wheels and wagons (wheel < kw(e)-kwlo < kwel ‘go around’) between the languages descended from it. Religion: priests, polytheistic with sun worship *deiw-os ‘shine’ cf. Lat. deus, Gk. The table below gives examples of historically related words in different languages which Zeus, Sanskrit deva. Patriarchal, cf. Zeus pater, Iupiter, Sanskr. dyaus pitar. show either similarities in pronunciation, or systematic differences. Example: most IE Trade/exchange:*do- yields Lat. donare ‘give’ and a Hittite word meaning ‘take’, languages have /p/ in the first two lines, suggesting that PIE originally had /p/ in these *nem- > German nehmen ‘take’ but in Gk. -

Influences on the Development of Early Modern English

Influences on the Development of Early Modern English Kyli Larson Wright This article covers the basic social, historical, and linguistic influences that have transformed the English language. Research first describes components of Early Modern English, then discusses how certain factors have altered the lexicon, phonology, and other components. Though there are many factors that have shaped English to what it is today, this article only discusses major factors in simple and straightforward terms. 72 Introduction The history of the English language is long and complicated. Our language has shifted, expanded, and has eventually transformed into the lingua franca of the modern world. During the Early Modern English period, from 1500 to 1700, countless factors influenced the development of English, transforming it into the language we recognize today. While the history of this language is complex, the purpose of this article is to determine and map out the major historical, social, and linguistic influences. Also, this article helps to explain the reasons for their influence through some examples and evidence of writings from the Early Modern period. Historical Factors One preliminary historical event that majorly influenced the development of the language was the establishment of the print- ing press. Created in 1476 by William Caxton at Westminster, London, the printing press revolutionized the current language form by creating a means for language maintenance, which helped English gravitate toward a general standard. Manuscripts could be reproduced quicker than ever before, and would be identical copies. Because of the printing press spelling variation would eventually decrease (it was fixed by 1650), especially in re- ligious and literary texts. -

Usage Patterns of Thou, Thee, Thy and Thine Among Latter-Day Saints

Deseret Language and Linguistic Society Symposium Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 8 4-8-1975 Usage Patterns of Thou, Thee, Thy and Thine Among Latter-day Saints Don Norton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/dlls BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Norton, Don (1975) "Usage Patterns of Thou, Thee, Thy and Thine Among Latter-day Saints," Deseret Language and Linguistic Society Symposium: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/dlls/vol1/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Deseret Language and Linguistic Society Symposium by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 7.1 USAGE PATTERNS OF I.IiQll, mEL Il:IY AND IlilJ:1E Ar·10NG LATTER-DAY SAINTS Don Norton Languages and Linguistics Symposium April 7-8, 1975 Brigham Young University 7.2 USAGE PATTERNS OF Jllill!., IilEL Il:lY. AND IlilliE. Ar10NG LATTER-DAY SAINTS Don Norton Until a couple of years ago, I had always (Selected from Vol. 2, pp. 14-15, Priesthood Manual, assumed that the counsel in the Church to use the pp. 183-4) . respect pronouns thou, thee, thy and thine applied only to converts, children, and a few inattentive Q. Is it important that we use the words adults. On listening more closely, however, I thy, thine, thee, and thou in address find cause for general concern. ing Deity; or is it proper vlhen direc ting our thoughts in prayer to use The illusion that we use these pronouns freely the more common and modern words, you and correctly stems, I think, from the fact that and yours? two of these pronouns, thee and thy, are common usage: thw presents few problems; the object case A. -

The English Language

The English Language Version 5.0 Eala ðu lareow, tæce me sum ðing. [Aelfric, Grammar] Prof. Dr. Russell Block University of Applied Sciences - München Department 13 – General Studies Winter Semester 2008 © 2008 by Russell Block Um eine gute Note in der Klausur zu erzielen genügt es nicht, dieses Skript zu lesen. Sie müssen auch die “Show” sehen! Dieses Skript ist der Entwurf eines Buches: The English Language – A Guide for Inquisitive Students. Nur der Stoff, der in der Vorlesung behandelt wird, ist prüfungsrelevant. Unit 1: Language as a system ................................................8 1 Introduction ...................................... ...................8 2 A simple example of structure ..................... ......................8 Unit 2: The English sound system ...........................................10 3 Introduction..................................... ...................10 4 Standard dialects ................................ ....................10 5 The major differences between German and English . ......................10 5.1 The consonants ................................. ..............10 5.2 Overview of the English consonants . ..................10 5.3 Tense vs. lax .................................. ...............11 5.4 The final devoicing rule ....................... .................12 5.5 The “th”-sounds ................................ ..............12 5.6 The “sh”-sound .................................. ............. 12 5.7 The voiced sounds / Z/ and / dZ / ...................................12 5.8 The -

ETH-2 Requests to Examine Seis.Pub

Request to Examine Statements of Economic Interests Your name Telephone number Email Address Street address City State Zip code I am making this request solely on my own behalf, independent of any other individual or organizaon. OR I am making this request on behalf of the individual or organizaon below. Requested on behalf of the following Individual or organizaon Telephone number Street address City State Zip code Year(s) Filed Name of individuals whose State‐ State agency or office held, or Format Requested (Each SEI covers the ment are requested posion sought previous calendar year) Electronic Printed Connue on the next page and aach addional pages as needed. W. S. §§ 19.48(8) and 19.55(1) require the Ethics Commission to obtain the above informaon and to nofy each offi‐ cial or candidate of the identy of a person examining the filer’s Statement of Economic Interests. I understand that use of a ficous name or address or failure to idenfy the person on whose behalf the request is made is a violaƟon of law. I un‐ derstand that any person who intenonally violates this subchapter is subject to a fine of up to $5,000 and imprisonment for up to one year. W. S. § 19.58(1). In accordance with W. S. § 15.04(1)(m), the Wisconsin Ethics Commission states that no personally idenfiable informaon is likely to be used for purposes other than those for which it is collected. ¥Ý: Statements are $0.15 per printed page (statements are at least four pages, plus any applicable aachments), and elec‐ tronic copies are $0.07 per PDF file. -

Phonetic and Phonological Petit Shifts

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Yamagata University Academic Repository Phonetic and phonological petit shifts TOMITA Kaoru (English phonetics) 山形大学紀要(人文科学)第17巻第3号別刷 平成 24 年(2012)2月 Phonetic and phonological petit shifts Phonetic and phonological petit shifts TOMITA Kaoru (English phonetics) Abstract Studies of language changes and their approaches are surveyed in this study. Among the changes, vowel shifts and consonant shifts observed in the history of language and modern English, and stress shifts in present-day English are introduced and discussed. Phonological studies of these sound changes, generally, present rules or restrictions. On this basis, it is proposed that consonant changes, vowel changes or stress shifts are better observed in several types of language or social contexts. It is especially emphasized that the phenomena of language changes in a real situation are to be found by observing words, phrases, sentences and even paragraphs spoken in quiet or hurried situations. Introduction Phonetic science states that language sound change is depicted as a phonetically conditioned process that originates through the mechanism of speech production. This standpoint is criticized from a large body of empirical evidence that has important consequences. Some propose frequency in use while others propose gender as the factor to explain sound changes. Sociolinguists claim that explanations that put an emphasis on language contexts or social contexts would lead the phonetic and phonological studies into the exploration of language sound changes in real situations. This paper surveys language sound changes, such as historical vowel shifts and consonant shifts, and stress shifts, with an explanation from the phonetic or social standpoints. -

Chapter ETH 26

Published under s. 35.93, Wis. Stats., by the Legislative Reference Bureau. 19 ETHICS COMMISSION ETH 26.02 Chapter ETH 26 SETTLEMENT OFFER SCHEDULE ETH 26.01 Definitions. ETH 26.03 Settlement of lobbying violations. ETH 26.02 Settlement of campaign finance violations. ETH 26.04 Settlement of ethics violations. ETH 26.01 Definitions. In this chapter: (15) “Preelection campaign finance report” includes the cam- (1) “15 day report” means the report referred to in s. 13.67, paign finance reports referred to in ss. 11.0204 (2) (b), (3) (a), (4) Stats. (b), and (5) (a), 11.0304 (2) (b), (3) (a), (4) (b), and (5) (a), 11.0404 (1m) “Business day” means any day Monday to Friday, (2) (b) and (3) (a), 11.0504 (2) (b), (3) (a), (4) (b), and (5) (a), excluding Wisconsin legal holidays as defined in s. 995.20, Stats. 11.0604 (2) (b), (3) (a), (4) (b), and (5) (a), 11.0804 (2) (b), (3) (a), (4) (b), and (5) (a), and 11.0904 (2) (b), (3) (a), (4) (b), and (5) (a), (2) “Commission” means the Wisconsin Ethics Commission. Stats., that are due no earlier than 14 days and no later than 8 days (3) “Continuing report” includes the campaign finance before an election. reports due in January and July referred to in ss. 11.0204 (2) (c), (16) “Preprimary campaign finance report” includes the cam- (3) (b), (4) (c) and (d), (5) (b) and (c), and (6) (a) and (b), 11.0304 paign finance reports referred to in ss. 11.0204 (2) (a) and (4) (a), (2) (c), (3) (b), (4) (c) and (d), and (5) (b) and (c), 11.0404 (2) (c) 11.0304 (2) (a) and (4) (a), 11.0404 (2) (a), 11.0504 (2) (a) and (4) and (d) and (3) (b) and (c), 11.0504 (2) (c), (3) (b), (4) (c) and (d), (a), 11.0604 (2) (a) and (4) (a), 11.0804 (2) (a) and (4) (a), and and (5) (b) and (c), 11.0604 (2) (c), (3) (b), (4) (c) and (d), and (5) 11.0904 (2) (a) and (4) (a), Stats., that are due no earlier than 14 (b) and (c), 11.0704 (2), (3) (a), (4) (a) and (b), and (5) (a) and (b), days and no later than 8 days before a primary. -

The Ideology of American English As Standard English in Taiwan

Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Volume.7 Number.4 December, 2016 Pp. 80 - 96 The Ideology of American English as Standard English in Taiwan Jackie Chang English Department, National Pingtung University Pingtung City, Taiwan Abstract English language teaching and learning in Taiwan usually refers to American English teaching and learning. Taiwan views American English as Standard English. This is a strictly perceptual and ideological issue, as attested in the language school promotional materials that comprise the research data. Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) was employed to analyze data drawn from language school promotional materials. The results indicate that American English as Standard English (AESE) ideology is prevalent in Taiwan. American English is viewed as correct, superior and the proper English language version for Taiwanese people to compete globally. As a result, Taiwanese English language learners regard native English speakers with an American accent as having the greatest prestige and as model teachers deserving emulation. This ideology has resulted in racial and linguistic inequalities in contemporary Taiwanese society. AESE gives Taiwanese learners a restricted knowledge of English and its underlying culture. It is apparent that many Taiwanese people need tore-examine their taken-for-granted beliefs about AESE. Keywords: American English as Standard English (AESE),Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), ideology, inequalities 80 Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Vol.7. No. 4 December 2016 The Ideology of American English as Standard English in Taiwan Chang Introduction It is an undeniable fact that English has become the global lingua franca. However, as far as English teaching and learning are concerned, there is a prevailing belief that the world should be learning not just any English variety but rather what is termed Standard English. -

Germanic Languages an Overview

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42186-7 — The Cambridge Handbook of Germanic Linguistics Edited by Michael T. Putnam , B. Richard Page Excerpt More Information Germanic Languages An Overview B. Richard Page and Michael T. Putnam I.1 Introduction The Germanic languages include some of the world’s most widely spoken and thoroughly researched languages. English has become a global lan- guage that serves as a lingua franca in many parts of the world and has an estimated 1.12 billon speakers (Simons and Fennig 2018). German, Dutch, Icelandic, Swedish, and Norwegian have also been studied and described extensively from both diachronic and synchronic perspectives. In addition to the standard varieties of these languages, there are available descrip- tions of many nonstandard varieties as well as of regional and minority languages, such as Frisian and Low German. There are several possibilities to consider when putting together a handbook of a language family. One would be to have a chapter devoted to each language, as in Ko¨nig and Auwera (1993). This would require the choice of which languages to include and would make cross-linguistic comparisons difficult. In the alternative, one could take a thematic, comparative approach and exam- ine different aspects of the Germanic languages, such as morphology or syntax, as in Harbert (2007). We have chosen the latter approach for this handbook. The advantage of such an approach is that it gives the contri- butors in the volume an opportunity to compare and contrast the broad range of empirical phenomena found across the Germanic languages that have been documented in the literature. -

Reference Guide for the History of English

Reference Guide for the History of English Raymond Hickey English Linguistics Institute for Anglophone Studies University of Duisburg and Essen January 2012 Some tips when using the Reference Guide: 1) To go to a certain section of the guide, press Ctrl-F and enter the name of the section. Alternatively, you can search for an author or the title of a book. 2) Remember that, for reasons of size, the reference guide only includes books. However, there are some subjects for which whole books are not readily available but only articles. In this case, you can come to me for a consultation or of course, you can search yourself. If you are looking for articles on a subject then one way to find some would be to look at a standard book on the (larger) subject area and then consult the bibliography at the back of the book., To find specific contents in a book use the table of contents and also the index at the back which always offers more detailed information. If you are looking for chapters on a subject then an edited volume is the most likely place to find what you need. This is particularly true for the history of English. 3) When you are starting a topic in linguistics the best thing to do is to consult a general introduction (usually obvious from the title) or a collection of essays on the subject, often called a ‘handbook’. There you will find articles on the subareas of the topic in question, e.g. a handbook on varieties of English will contain articles on individual varieties, a handbook on language acquisition will contain information on various aspects of this topic.