Typology and Distribution in Pokhara Lekhnath Metropolitan City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

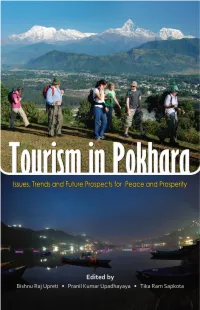

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity 1 Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity Edited by Bishnu Raj Upreti Pranil Kumar Upadhayaya Tikaram Sapkota Published by Pokhara Tourism Council, Pokhara South Asia Regional Coordination Office of NCCR North-South and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research, Kathmandu Kathmandu 2013 Citation: Upreti BR, Upadhayaya PK, Sapkota T, editors. 2013. Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity. Kathmandu: Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), South Asia Regional Coordination Office of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North- South) and Nepal Center for Contemporary Research (NCCR), Kathmandu. Copyright © 2013 PTC, NCCR North-South and NCCR, Kathmandu, Nepal All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-9937-2-6169-2 Subsidised price: NPR 390/- Cover concept: Pranil Upadhayaya Layout design: Jyoti Khatiwada Printed at: Heidel Press Pvt. Ltd., Dillibazar, Kathmandu Cover photo design: Tourists at the outskirts of Pokhara with Mt. Annapurna and Machhapuchhre on back (top) and Fewa Lake (down) by Ashess Shakya Disclaimer: The content and materials presented in this book are of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North-South) and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research (NCCR). Dedication To the people who contributed to developing Pokhara as a tourism city and paradise The editors of the book Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity acknowledge supports of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC) and the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South, co-funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and the participating institutions. -

An Overview of Tourism Diversity in Nepal

Patan Pragya (Volume: 6, Number: 1 2020) Received Date: Jan. 2020 Revised: April 2020 Accepted: June 2020 An Overview of Tourism Diversity in Nepal Minesh Kumar Ghimire Abstract Tourism is the most important service industry of Nepal. It provided big opportunities of national development and income to maintain international harmony. It will argue the more descriptive nature of information. The diversity of tourism has a huge benefit of tourism development. The tourism activities in Nepal are different attractions such as adventure, natural, cultural etc. The Airway is means of Tourist Arrival means of Nepal and Average Length of Stay is 12 days. Key Words: Tourism activities, Tourism Opportunities, diversity, Eco-tourism. Background Tourism is one of the important factors in the economic sector of Nepal. It doesn’t just create employment opportunities but attracts many international tourists which bring in foreign currency. In this regard, to have more international tourist means to be in more foreign currency and as the exchange rate varies, the foreign currency can be a boon for the economic progress of the country. People working in the tourism industry are the direct beneficiary but the people working in agriculture, airlines, hospital, hotels are the indirect beneficiary. The products from the indirect beneficiary can be promoted via tourism and get to the international market as well. It helps people to understand each other and respect each other which helps to maintain harmony in the country and around the world. Various relevant policy documents, proceedings of various seminars, study reports and such other documents can be reviewed for extracting secondary information of tourism and how tourism has been influential in the life of people who are dependent on it. -

![Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7316/wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-cggk-0f-if0f-if-qsf-tgwf-l-jgohgt-wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-2019-127316.webp)

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019 ISBN 978-9937-8522-8-9978-9937-8522-8-9 9 789937 852289 National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project Khumaltar, Lalitpur, Nepal Hariyo Kharka, Pokhara, Kaski, Nepal National Trust for Nature Conservation P.O. Box: 3712, Kathmandu, Nepal P.O. Box: 183, Kaski, Nepal Tel: +977-1-5526571, 5526573, Fax: +977-1-5526570 Tel: +977-61-431102, 430802, Fax: +977-61-431203 Annapurna Conservation Area Project Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.ntnc.org.np Website: www.ntnc.org.np 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Published by © NTNC-ACAP, 2019 All rights reserved Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit NTNC-ACAP. Reviewers Prof. Karan Bahadur Shah (Himalayan Nature), Dr. Naresh Subedi (NTNC, Khumaltar), Dr. Will Duckworth (IUCN) and Yadav Ghimirey (Friends of Nature, Nepal). Compilers Rishi Baral, Ashok Subedi and Shailendra Kumar Yadav Suggested Citation Baral R., Subedi A. & Yadav S.K. (Compilers), 2019. Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area. National Trust for Nature Conservation, Annapurna Conservation Area Project, Pokhara, Nepal. First Edition : 700 Copies ISBN : 978-9937-8522-8-9 Front Cover : Yellow-bellied Weasel (Mustela kathiah), back cover: Orange- bellied Himalayan Squirrel (Dremomys lokriah). -

Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal

IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal Country Name Nepal Official Name Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Regional Bureau Bangkok, Thailand Assessment Assessment Date: From 16 October 2009 To: 6 November 2009 Name of the assessors Rich Moseanko – World Vision International John Jung – World Vision International Rajendra Kumar Lal – World Food Programme, Nepal Country Office Title/position Email contact At HQ: [email protected] 1/105 IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Country Profile....................................................................................................................................................................3 1.1. Introduction / Background.........................................................................................................................................5 1.2. Humanitarian Background ........................................................................................................................................6 1.3. National Regulatory Departments/Bureau and Quality Control/Relevant Laboratories ......................................16 1.4. Customs Information...............................................................................................................................................18 2. Logistics Infrastructure .....................................................................................................................................................33 2.1. Port Assessment .....................................................................................................................................................33 -

Invitation for Bids

Invitation for Bids Government of Nepal (GoN) Rupa Rural Municipality Invitation for Bids for the Supply and Delivery of HDPE Pipe Contract Identification No: NCB/GOODS/RUPA/2075/76-01 Date of publication: 03-03-2019 10:00 1. The Government of Nepal has allocated funds to cover eligible payment under the Contract for Supply and Delivery of HDPE Pipe (IFB No: NCB/GOODS/RUPA/2075/76-01). Bidding is open to all eligible Nepaleses. 2. Rupa Rural Municipality invites electronic bids from eligible bidders for the procurement of Supply and Delivery of HDPE Pipe of Rupa Rural Municipality under National Competitive Bidding procedures. 3. Eligible Bidders may obtain further information and inspect the Bidding Documents at the office of Rupa Rural Municipality Rupa Rural Municipality Rupakot,Kaski Nepal or may visit PPMO website www.bolpatra.gov.np/egp. 4. A complete set of Bidding Documents may be purchased from the following bank/office by eligible Bidders on the submission of a written application, along with the copy of company/firm registration certificate, and upon payment of a non-refundable fee of 3000.0 NRs till 02-04-2019 12:00. If so requested Bidding Documents can also be sent by post/ service upon payment of additional fee for post/courier. However the Employer will not be responsible for delay or non-delivery of the document to sent Name of the Bank: Sunrise Bank Ltd. , POKHARA BRANCH ,Pokhara Kathmandu Name of the Office: Rupa Rural Municipality Office Code no: 47-365-11 Office Account no: 0720518864703001 5. Electronic bids must be submitted to the office Rupa Rural Municipality ,Raupakot,Kaski Rupakot, Kaski Nepal through PPMO website www.bolpatra.gov.np. -

Integrated Lake Basin Management Plan of Lake Cluster of Pokhara Valley, Nepal (2018-2023)

Integrated Lake Basin Management Plan Of Lake Cluster of Pokhara Valley, Nepal (2018-2023) Nepal Valley, Pokhara of Cluster Lake Of Plan Management Basin Lake Integrated INTEGRATED LAKE BASIN MANAGEMENT PLAN OF LAKE CLUSTER OF POKHARA VALLEY, NEPAL (2018-2023) Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-1- 4211567, Fax: +977-1-4211868 Government of Nepal Email: [email protected], Website: www.mofe.gov.np Ministry of Forests and Environment INTEGRATED LAKE BASIN MANAGEMENT PLAN OF LAKE CLUSTER OF POKHARA VALLEY, NEPAL (2018-2023) Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Publisher: Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Citation: MoFE, 2018. Integrated Lake Basin Management Plan of Lake Cluster of Pokhara Valley, Nepal (2018-2023). Ministry of Forests and Environment, Kathmandu, Nepal. Cover Photo Credits: Front cover - Rupa and Begnas Lake © Amit Poudyal, IUCN Back cover – Begnas Lake © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Nabin Baral © Ministry of Forests and Environment, 2018 Acronyms and Abbreviations ACA Annapurna Conservation Area ADB Asian Development Bank ARM Annapurna Rural Municipality BCN Bird Conservation Nepal BLCC Begnas Lake Conservation Cooperative BMP Budhi Bazar Madatko Patan CBD Convention on Biological Diversity CBS Central Bureau of Statistics CF Community Forest CFUG Community Forest User Group CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora DADO District Agriculture Development Office DCC District Coordination -

Water Quality in Pokhara: a Study with Microbiological Aspects

A Peer Reviewed TECHNICAL JOURNAL Vol 2, No.1, October 2020 Nepal Engineers' Association, Gandaki Province ISSN : 2676-1416 (Print) Pp.: 149- 161 WATER QUALITY IN POKHARA: A STUDY WITH MICROBIOLOGICAL ASPECTS Kishor Kumar Shrestha Department of Civil and Geomatics Engineering Pashchimanchal Campus, Pokhara E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Obviously, water management is challenging issue in developing world. Dwellers of Pokhara use water from government supply along with deep borings and other sources as well. Nowadays, people are also showing tendency towards more use of processed water. In spite of its importance, quality analysis of water has been less emphasized by concerned sectors in our cities including Pokhara. The study aimed for qualitative analysis of water in the city with focus on microbiological aspects. For this purpose, results of laboratory examination of water samples from major sources of government supply, deep borings, hospitals, academic institutions as well as key water bodies situated in Pokhara were analyzed. Since water borne diseases are considered quite common in the area, presence of coliform bacteria was considered for the study to assess the question on availability of safe water. The result showed that all the samples during wet seasons of major water sources of water in Pokhara were contaminated by coliform bacteria. Likewise, in all 20 locations of Seti River, the coliform bacteria were recorded. Similar results with biological contamination in all samples were observed after laboratory examination of more than 60 locations of all three lakes: Phewa Lake, Begnas Lake and Rupa Lake in Pokhara. The presence of such bacteria in most of the water samples of main sources during wet seasons revealed the possibilities of spreading water related diseases. -

Prithvi Academic Journal

PRITHVI ACADEMIC JOURNAL Prithvi Academic Journal (A Peer-Reviewed, Open Access International Journal) ISSN 2631-200X (Print); ISSN 2631-2352 (Online) Volume 3; May 2020 Trends of Temperature and Rainfall in Pokhara Upendra Paudel, Associate Professor Department of Geography, Prithvi Narayan Campus Tribhuvan University, Nepal ABSTRACT Climate is an average condition of temperature, humidity, air pressure, wind, precipitation and other meteorological elements. It is a changing phenomenon. Natural processes and human activities have helped change the climate. Temperature is a vital element of climate, which fluctuates in the course of time and leads to change other elements of the whole climate. An attempt has been made to analyze the pattern of temperature and rainfall of Pokhara with the help of the two decades’ temperature and rainfall conditions obtained from the station of Pokhara airport. The increasing trend of temperature and the decreasing trend of rainfall might be the symbol of climatic modification. This trend refers to some changes in the climatic condition that may affect water resources, vegetation, forests and agriculture. KEYWORDS: Adaptation, climate, climatic modification, desertification, environmental problem, fluctuation, greenhouse gases INTRODUCTION Climate is an aggregate of atmospheric conditions including, humidity, air pressure, wind, precipitation and other meteorological elements in a given area over a long period of time (Critchfield, 1990). It is not ever static but a changeable phenomenon. Such type of change occurs in quality and quantity of the components of climate like temperature, air pressure, humidity, rainfall, etc. Natural and man-induced factors are responsible for the modification of climate. It is a global issue faced by every living thing of the world. -

Chitwan District Jail Bharatpur Alt: 240 M Amsl

E v a l u a t i o n o f b i o g a s s a n i t a t i o n s y s t e m s i n N e p a l e s e p r i s o n s S a n d e c Water and Sanitation in Developing Countries E v a l u a t i o n o f b i o g a s s a n i t a t i o n s y s t e m s i n N e p a l e s e p r i s o n s Summary Presentation of Evaluation Results August 09 E v a l u a t i o n o f b i o g a s s a n i t a t i o n s y s t e m s i n N e p a l e s e p r i s o n s T a b l e o f c o n t e n t s 1. Introduction 1. Introduction 1.1 Background 2. Monitoring 1.2 Objectives 1.3 Methodologies 3. Evaluation 2. Monitoring 2.1 Monitored systems 4. Discussion 2.2 Treatment efficiency 2.3 Biogas 3. Evaluation 3.1 Technical 3.2 Organizational 3.3 Economic 3.4 Environmental 3.5 Socio-cultural 3.6 Sanitation/Health 4. Discussion 4.1 Recommendation 4.2 Conclusion E v a l u a t i o n o f b i o g a s s a n i t a t i o n s y s t e m s i n N e p a l e s e p r i s o n s B a c k g r o u n d 1. -

Vulnerability and Impacts Assessment for Adaptation Planning In

VULNERABILITY AND I M PAC T S A SSESSMENT FOR A DA P TAT I O N P LANNING IN PA N C H A S E M O U N TA I N E C O L O G I C A L R E G I O N , N EPAL IMPLEMENTING AGENCY IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS SUPPORTED BY Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation, Department of Forests UNE P Empowered lives. Resilient nations. VULNERABILITY AND I M PAC T S A SSESSMENT FOR A DA P TAT I O N P LANNING IN PA N C H A S E M O U N TA I N E C O L O G I C A L R E G I O N , N EPAL Copyright © 2015 Mountain EbA Project, Nepal The material in this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit uses, without prior written permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. We would appreciate receiving a copy of any product which uses this publication as a source. Citation: Dixit, A., Karki, M. and Shukla, A. (2015): Vulnerability and Impacts Assessment for Adaptation Planning in Panchase Mountain Ecological Region, Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal: Government of Nepal, United Nations Environment Programme, United Nations Development Programme, International Union for Conservation of Nature, German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety and Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-Nepal. ISBN : 978-9937-8519-2-3 Published by: Government of Nepal (GoN), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) and Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-Nepal (ISET-N). -

Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025 Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Strategy Andactionplan2016-2025|Chitwan-Annapurnalandscape,Nepal

Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025 Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Strategy andActionPlan2016-2025|Chitwan-AnnapurnaLandscape,Nepal Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-1- 4211567, 4211936 Fax: +977-1-4223868 Website: www.mfsc.gov.np Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025 Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Publisher: Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Citation: Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation 2015. Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025, Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Cover photo credits: Forest, River, Women in Community and Rhino © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Nabin Baral Snow leopard © WWF Nepal/ DNPWC Rhododendron © WWF Nepal Back cover photo credits: Forest, Gharial, Peacock © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Nabin Baral Red Panda © Kamal Thapa/ WWF Nepal Buckwheat fi eld in Ghami village, Mustang © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Kapil Khanal Women in wetland © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Kashish Das Shrestha © Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Acronyms and Abbreviations ACA Annapurna Conservation Area asl Above Sea Level BZ Buffer Zone BZUC Buffer Zone User Committee CA Conservation Area CAMC Conservation Area Management Committee CAPA Community Adaptation Plans for Action CBO Community Based Organization CBS -

Willingness and Status of Social Health Insurance Among People of Pokhara Lekhnath, Nepal

Willingness And Status Of Social Health Insurance Among People Of Pokhara Lekhnath, Nepal Manju Adhikari ( [email protected] ) La Grandee International College https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7032-5092 Nandram Gahatraj Pokhara University Research article Keywords: Awareness, Nepal, Social Health Insurance, Willingness, Knowledge, health insurance Posted Date: March 18th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-17840/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License WILLINGNESS AND STATUS OF SOCIAL HEALTH INSURANCE AMONG PEOPLE OF POKHARA LEKHNATH, NEPAL Authors: 1st: Manju Adhikari (Student, Master of Public Health, Central Queensland University, Melbourne, Australia) 2nd: Nand Ram Gahatraj (Assist Prof., School of Health and Allied Sciences, Pokhara University, Nepal) 1 ABSTRACT Background: Social health insurance program was implemented in Nepal with the aim to achieve universal health coverage by removing health and financial barriers to access health care. This study was performed to assess the willingness and status of social health insurance among people of Pokhara Lekhnath, Nepal. Methods: A cross-sectional study was performed using mixed method. Quantitative study was conducted among 339 participants using interview schedule and qualitative among 27 participants using focus group discussion guidelines. Quantitative data was entered in Epi-data and descriptive analysis done in Statistical Package for Social Sciences. Chi-square tests was used for quantitative data to explore associations. Qualitative data was analyzed thematically keeping verbatim. Results: Among 339 participants, 51% were willing to pay and 77% were willing to continue, majority were due to the provision of free health services. About quarter enrolled participants were thinking about discontinuation due to lack of quality services.