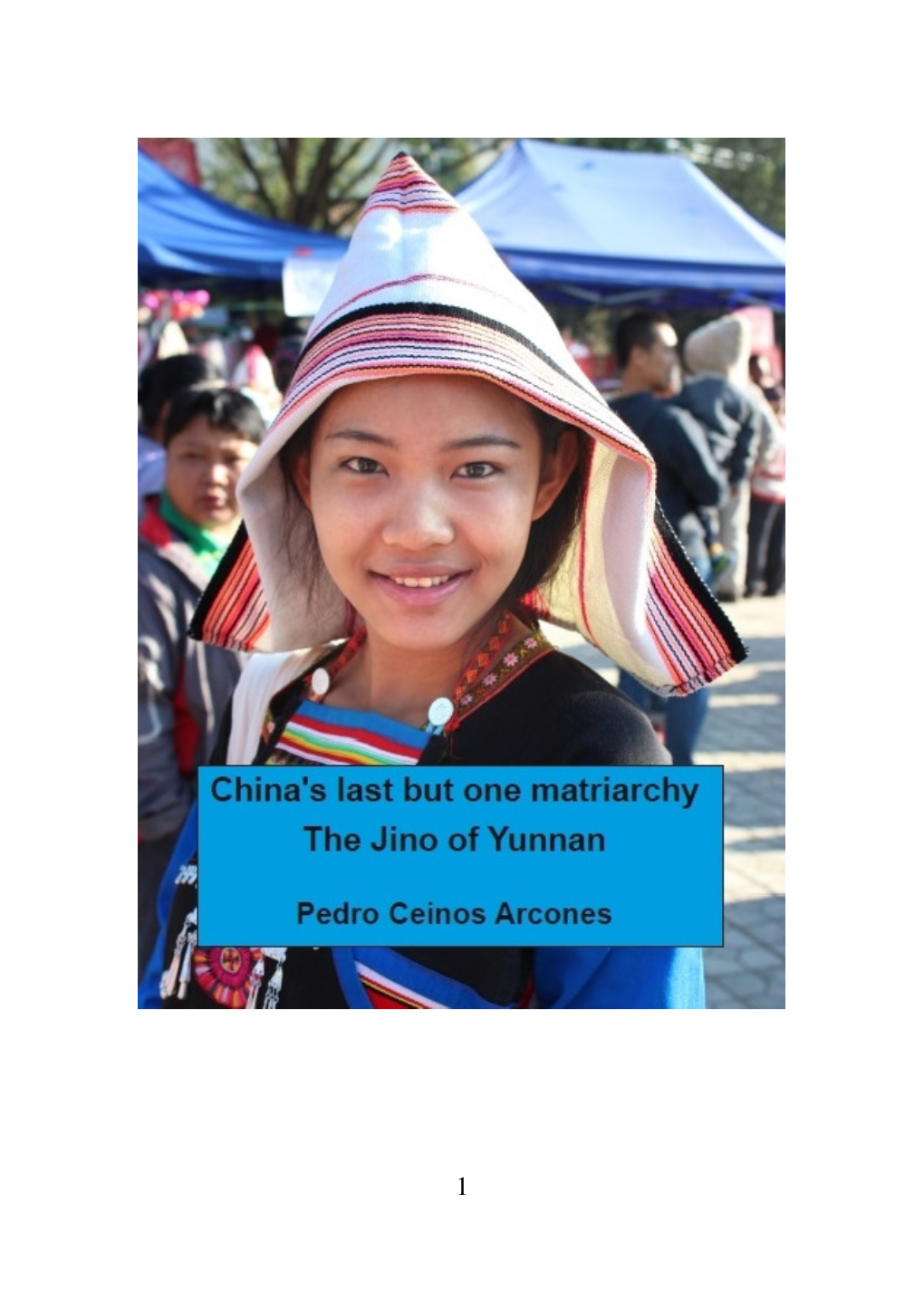

China's Last but One Matriarchy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loanwords in Youle Jino

The 23rd Annual Meeting for Southeast Asian Linguistic Society Chulalongkorn University (Bangkok, Thailand) 29th-31st, May, 2013 Loanwords in Youle Jino Norihiko Hayashi Kobe City University of Foreign Studies [email protected] 1. Introduction 1.1 Language Background [Genealogy]: Lolo-Burmese, Tibeto-Burman, Sino-Tibetan [Area]: Sipsongpanna (Xishuangbanna), Yunnan, China [Population]: 20,899 (2000 census) [Dialects]: Youle (90%), Buyuan (10%) 1.2 Linguistic Situation of Sipsongpanna (Xishuangbanna) Area [Dominant Language] Tai Lue (~1950) > Chinese (1950~) [Linguistic Groups] Chinese Tibeto-Burman: Akha, Akeu, Lahu, Jino, Sangkong, Bisu Tai-Kadai: Tai Lue Miao-Yao: Miao, Yao Mon-Khmer: Wa, Blang, Bit, Khmu Map: Youle Jino villages (adapted from Kato 2000) 1 / 16 1.3 Aim of This Paper a) Describing loanwords in Youle Jino, utilizing my first hand data1 b) Investigating the phonological, morphological and semantic features of Youle Jino loanwords 2. Prevous Works a) Gai, Xingzhi (盖兴之): Gai (1981, 1986) Description of Youle Jino, Comparison between Youle and Buyuan b) Hayashi, Norihiko (林範彦): Hayashi (2009a, b), etc. Descriptive Grammar of Youle Jino (2009a), Historical Development of Youle Jino (2009b), Various Topics in Youle Jino Grammar (2010, 2013, etc.) c) Jiang, Guangyou (蒋光友): Jiang (2010) Descriptive Grammar of Youle Jino ♦Loanwords Haspelmath and Tadmor (2009) 3. Phonology 3.1 Onset ►Onset Inventories p ph t th k kh ts tsh tʃ tʃh tɕ tɕh m m̥ n n̥ ȵ ȵ̥ ŋ ŋ̥ l l̥ f s ʃ ç x v z r j ɣ (w) 1 The fieldworks carried out on Youle Jino commenced from 2000. I wish to express my deepest gratitude to Ms. -

Phonological Sketch of the Sida Language of Luang Namtha, Laos1

Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society JSEALS Vol. 10.1 (2017): 1-15 ISSN: 1836-6821, DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10524/52394 University of Hawaiʼi Press eVols PHONOLOGICAL SKETCH OF THE SIDA LANGUAGE OF 1 LUANG NAMTHA, LAOS Nathan BADENOCH, Kyoto University The Center for Southeast Asian Studies [email protected] HAYASHI Norihiko Kobe City University of Foreign Studies [email protected] Abstract This paper describes the phonology of the Sida language, a Tibeto-Burman language spoken by approximately 3,900 people in Laos and Vietnam. The data presented here are the variety spoken in Luang Namtha province of northwestern Laos, and focuses on a synchronic description of the fundamentals of the Sida phonological systems. Several issues of diachronic interest are also discussed in the context of the diversity of the Southern Loloish group of languages, many of which are spoken in Laos and have not yet been described in detail. Keywords: Sida, Loloish, phonology, Laos ISO 639-3 codes: slt 1 Introduction This paper provides a first overview of the phonology of the Sida language [ISO: slt], a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in Northern Laos and Northern Vietnam. The data presented here are representative of one dialect spoken in Luang Namtha province of Laos. 1.1 The Sida language and its speakers According to the 2015 census of Laos, there are 3,151 ethnic Sida people in Laos, and it is believed that all speak the Sida language. There are Sida speakers in Vietnam as well, and the total of speakers in both countries has been estimated at around 3,900 (Lewis 2014). -

Sanie and Language Loss in China*

Sanie and language loss in China* DAVID BRADLEY Abstract Most of the many languages spoken by the large and widely distributed Yi nationality in China are endangered. One such is Sanie, spoken by about 8,000 people from a group of over 17,000 near Kunming in Yunnan. In surveying the area around Kuming, we located Sanie and a number of other undescribed and in most cases unreported endangered languages. Sanie is remarkable in that in some dialects it preserves velar plus /w/ clusters which have been simplified in all other closely related languages. Such a cluster is found in the group name; this gives us a clearer understanding of the original autonym for the Yi languages as a whole. Therefore, the new name Ngwi for this group of languages is proposed, with etymological justi- fications. Sanie also has a large range of internal di¤erences, suggesting that processes of change are speeded up during the process of language death. However it is shown to be a typical Eastern Yi language, like several of the other endangered languages spoken around Kunming including Sa- mataw and Samei. 1. The Yi nationality1 The Yi are one of China’s 55 minority nationalities, with a population of nearly eight million. They live in the southwest of the country; especially in Yunnan, southwestern Sichuan and western Guizhou Provinces, with a few also in western Guangxi. There are a couple of groups within Yi in south central Yunnan who also spread into northern Vietnam, and one into northeastern Laos. They are extremely heterogeneous but classified together by the Chinese. -

PART I: NAME SEQUENCE Name Sequence

Name Sequence PART I: NAME SEQUENCE A-ch‘ang Abor USE Achang Assigned collective code [sit] Aba (Sino-Tibetan (Other)) USE Chiriguano UF Adi Abaknon Miri Assigned collective code [phi] Miśing (Philippine (Other)) Aborlan Tagbanwa UF Capul USE Tagbanua Inabaknon Abua Kapul Assigned collective code [nic] Sama Abaknon (Niger-Kordofanian (Other)) Abau Abujhmaria Assigned collective code [paa] Assigned collective code [dra] (Papuan (Other)) (Dravidian (Other)) UF Green River Abulas Abaw Assigned collective code [paa] USE Abo (Cameroon) (Papuan (Other)) Abazin UF Ambulas Assigned collective code [cau] Maprik (Caucasian (Other)) Acadian (Louisiana) Abenaki USE Cajun French Assigned collective code [alg] Acateco (Algonquian (Other)) USE Akatek UF Abnaki Achangua Abia Assigned collective code [sai] USE Aneme Wake (South American (Other)) Abidji Achang Assigned collective code [nic] Assigned collective code [sit] (Niger-Kordofanian (Other)) (Sino-Tibetan (Other)) UF Adidji UF A-ch‘ang Ari (Côte d'Ivoire) Atsang Abigar Ache USE Nuer USE Guayaki Abkhaz [abk] Achi Abnaki Assigned collective code [myn] USE Abenaki (Mayan languages) Abo (Cameroon) UF Cubulco Achi Assigned collective code [bnt] Rabinal Achi (Bantu (Other)) Achinese [ace] UF Abaw UF Atjeh Bo Cameroon Acholi Bon (Cameroon) USE Acoli Abo (Sudan) Achuale USE Toposa USE Achuar MARC Code List for Languages October 2007 page 11 Name Sequence Achuar Afar [aar] Assigned collective code [sai] UF Adaiel (South American Indian Danakil (Other)) Afenmai UF Achuale USE Etsako Achuara Jivaro Afghan -

A Phonological Sketch of Akha Buli --- a Lolo-Burmese Language of Muang Sing, Laos

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kobe City University of Foreign Studies Institutional Repository ⚄ᡞᕷእᅜㄒᏛ እᅜᏛ◊✲ ࢪゝㄒㄽྀ A Phonological Sketch of Akha Buli --- A Lolo-Burmese language of Muang Sing, Laos --- HAYASHI Norihiko 1. Introduction The Akha language is a member of the Akoid languages of the Lolo (Yipho)-Burmese branch of Tibeto-Burman linguistic stock (Bradley 1997). It is spoken widely across Mainland Southeast Asia, in areas such as Yunnan Province of China, Northern Thailand, Northern Burma/Myanmar, Northern Laos, and Northern Vietnam. Hansson (2003: 236) states that there are approximately 250,000 in China, 45,000 in Thailand, 200,000 in Burma/Myanmar, 100,000 in Laos, and 7,000 in Vietnam, though population figures are not reliable. The Akha language has many linguistic varieties, like Akha Chicho, Akha Chepya, Akha Ulo, etc. This paper utilizes first-hand data1 to illustrate the basic phonology and lexicon of Akha Buli (Puli),2 which is an Akha variety spoken at Phabaad Noy Village in the district of Muang Sing in Luang Namtha Province, Laos (see Map 1). An orientation to the paper follows. Section 2 introduces previous studies on the Akha Buli language. Sections 3 to 6 describe the synchronic phonology of this language, whereby Section 3 deals with syllable structure, Section 4 illustrates the consonants, Section 5 presents the vowels, and Section 6 outlines the tones. Finally, Section 7 concludes this paper. Moreover, a basic word list is added as Appendix at the last part of this paper. -

Everyday Information Practices of Ethnic Minorities with Small Populations in Yunnan, China

Malaysian Journal of Library & Information Science, Vol. 26, no. 1, April 2021: 1-15 Everyday information practices of ethnic minorities with small populations in Yunnan, China Ming Zhu* and Xizhu Liao School of History and Archive, 2 Cuihu N Rd, Kunming, Yunnan University, 650106, CHINA e-mail: *[email protected] (corresponding author); [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper explores the everyday information practices of ethnic minorities with small populations (EMSP) to identify the conditions that affect their information practices within the context of Chinese culture. A qualitative study was conducted with China’s ethnic minorities, and data were collected through in-depth interviews and observations involving 45 participants. The data were statistically analyzed and processed using three levels of qualitative data coding analysis to identify the conditions that affect their everyday information practices. Findings show that the information needs of EMSP in China are relatively centralized, their sources of information acquisition are relatively fixed, and they do not cross ethnic group boundaries to share information with the outside world. In addition, traditions, customs, lifestyle, and ethnic identity are the conditions that influenced their everyday information practices. These results further the understanding of ethnic characteristics and traditional culture as conditions that can influence everyday information practices. Keywords: Ethnic minorities; Small populations; Everyday information practice; Information needs; Information behaviour. INTRODUCTION Information technologies and theoretical guidance both play important roles in social inclusion and integration for marginalized and minority populations in modern society. Interdisciplinary researchers from library and information science (LIS), sociology, and communication have been investigating how information-seeking, distribution, and use can offset the digital divide and exclusion of underserved and marginalized social groups. -

For Peer Review Only

BMJ Open BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010047 on 29 December 2015. Downloaded from Mutation Screening for Thalassaemia in the Jino Ethnic Minority Population of Yunnan Province, Southwest China ForJournal: peerBMJ Open review only Manuscript ID bmjopen-2015-010047 Article Type: Research Date Submitted by the Author: 20-Sep-2015 Complete List of Authors: Wang, Shiyun; Shanghai Diabetes Institute, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Diabetes Mellitus, Shanghai Clinical Center for Diabetes, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth, Zhang, Rong; Shanghai Diabetes Institute, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Diabetes Mellitus, Shanghai Clinical Center for Diabetes, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth, Xiang, Guangxin; National Engineering Research Center for Beijing Biochip Technology, Li, Yang; National Engineering Research Center for Beijing Biochip Technology, Hou, Xuhong; Shanghai Diabetes Institute, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Diabetes Mellitus, Shanghai Clinical Center for Diabetes, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth, Jiang, Fusong; Shanghai Diabetes Institute, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Diabetes Mellitus, Shanghai Clinical Center for Diabetes, Shanghai Jiao http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ Tong University Affiliated Sixth, Jiang, Feng; Shanghai Diabetes Institute, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Diabetes Mellitus, Shanghai Clinical Center for Diabetes, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth, Hu, Cheng; Shanghai Diabetes Institute, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Diabetes Mellitus, Shanghai Clinical Center for Diabetes, -

Title <Phonology> Notes on the Phonological Development of Menglun Akeu Author(S) HAYASHI Norihiko Citation Grammatical Ph

<Phonology> Notes on the Phonological Development of Title Menglun Akeu Author(s) HAYASHI Norihiko Grammatical Phenomena of Sino-Tibetan Languages 4: Link Citation languages and archetypes in Tibeto-Burman (2021): 1-23 Issue Date 2021-03-20 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/263976 Right Type Book Textversion publisher Kyoto University Nagano Yasuhiko and Ikeda Takumi (eds.) Grammatical Phenomena of Sino-Tibetan Languages 4: 1–23, 2021 Link Languages and Archetypes in Tibeto-Burman Notes on the Phonological Development of Menglun Akeu* Hayashi Norihiko Kobe City University of Foreign Studies Summary This paper attempts to investigate the phonological development of Menglun Akeu, a lesser-known Tibeto-Burman language spoken in Mengla County of Yunnan Province of China. Using the author’s firsthand data of Menglun Akeu and two related languages (Akha Buli and Youle Jino), both segments and suprasegments of the language are com- pared with those of written Burmese and the proto languages reconstructed by David Bradley and James A. Matisoff. The stop and affricate onsets in Menglun Akeu mostly preserve the VOT system of the Proto-Loloish or the Proto-Lolo-Burmese, whereas the fricative in Menglun Akeu corre- sponds to Lolo-Burmese languages in a complicated manner. The medial /-j-/ can be pre- ceded by the velar onsets (/k-, g-/) in Menglun Akeu, which in some cases (‘to steal’ and ‘nine’) corresponds only to Youle Jino in the dataset of this paper. Syllabic nasal /n/ can be found in Menglun Akeu, which is the outcome of deleting the rime. The rime correspondence between Menglun Akeu and other Lolo-Burmese is complex, although there are a few corresponding rules [Menglun Akeu: Proto-Loloish = -i: *-ey/ *-i, -ɛ: -*am, -a: *-a, -u: *-u, etc.]. -

MARC Code List for Languages

MARC Code List for Languages MARC 21 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS ■ 2007 MARC Code List for Languages 2007 Edition Prepared by Network Development and MARC Standards Office Library of Congress LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING DISTRIBUTION SERVICE / WASHINGTON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MARC code list for languages / prepared by Network Development and MARC Standards Office, Library of Congress. — 2007 ed. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-8444-1163-7 1. MARC formats. 2. Language and languages — Code words. I. Library of Congress. Network Development and MARC Standards Office. Z699.35.M28 U79 2007 025.3'16—dc22 2006103410 Available in the U.S.A. and other countries from: Cataloging Distribution Service, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20541-4912 U.S.A. Copyright © 2007 by the Library of Congress except within the U.S.A. This publication may be reproduced without permission provided the source is fully acknowledged. This publication will be reissued from time to time as needed to incorporate revisions. Contents CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.5 PART I: NAME SEQUENCE.11 PART II: CODE SEQUENCE.161 APPENDIX: CHANGES.167 MARC Code List for Languages October 2007 page 3 — page 4 Introduction INTRODUCTION This document contains a list of languages and their associated three-character alphabetic codes. The purpose of this list is to allow the designation of the language or languages in MARC records. The list contains 484 discrete codes, of which 55 are used for groups of languages. CHANGES IN 2007 EDITION This list includes all valid codes and code assignments as of September 2007. There are 27 code additions and 12 changed code captions in this revision. -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & Unreached People Groups of China Source: Joshua Project Data

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups of China Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] I give credit & thanks to Asia Harvest for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer & Devotional Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs of China SUMMARY: 544 total People Groups; (+Hong Kong & Macau) 443 JP Least Reached = LR-UPG = shaded; Downloaded & updated from www.joshuaproject.net in August, 2020 LR-UPG: less than 2% Evangelical & less than 5% total Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." * * * Let's dream God's dreams, and fulfill God's visions -- God dreams of all people groups knowing & loving Him! * * * Revelation 7:9, "After this I looked and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. 3:15! * In the Great Commissions Jesus commands us to reach all peoples in the world, Matt. 28:19-20! * People without Jesus are eternally lost, & Jesus is the only One who can save them, John 14:6! * We have been given "the ministry & message of reconciliation", in Christ, 2 Cor. -

Dynamics of Language Contact in China: Ethnolinguistic Diversity and Variation in Yunnan

University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa PhD Dissertation Dynamics of Language Contact in China: Ethnolinguistic Diversity and Variation in Yunnan Katie B. Gao 2017 A dissertation submitted to the UHM Graduate Division in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics Dissertation committee: Katie Drager, Chairperson Andrea Berez-Kroeker David Bradley Lyle Campbell Everett Wingert 献给纾含和她的家人 For Shuhan and her family Acknowledgments This dissertation is by no means a product of just one person but was made possible by generous funding agencies, patient mentors and research partners, and encouraging friends and family. I am grateful to the following groups who fnancially supported the research that led to this dissertation: the National Science Foundation, for feld research to supplement the Catalogue of Endangered Languages; the Bilinski Educational Foundation, for feld research and proposal development; the UH Mānoa College of Arts and Sciences for feld research; the UH Mānoa College of Languages, Linguistics and Literature, for dissertation development; the UH Mānoa Graduate Student Organization, for conference funding; and the Department of Linguistics for making my graduate student career fnancially feasible. I would like to thank my chair and mentor, Katie Drager, for her practical guidance on papers, professional development, and life in general. I am a better thinker and writer because of your whys and so whats over the years. To the rest of my wonderful committee: Andrea, thank you for being a steady support with your always-sound advice throughout my time at UH ; Lyle, thank you for your willingness to help at any time with any question or issue from theory to funding; David, thank you for being a source of information and encouragement from the beginning of my interest to pursue research in Yunnan; and Ev, thank you for sharing your love of cartographic design through your teaching and stories, you’re a main reason why there are maps in my dissertation. -

2020 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups

2020 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups of China Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] 2020 Daily Prayer & Devotional Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs of China SUMMARY: China: 544 total People Groups; (+HK & Macau) China: 445 JP Least Reached = LR-UPG = shaded; Download & update from www.joshuaproject.net in July, Dec. 2019 LR-UPG: less than 2% Evangelical & less than 5% total Christian Frontier = FR = 0.1% Christian or less I give credit & thanks to Asia Harvest for permission to use their PG photos. Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." * * * Let's dream God's dreams, and fulfill God's visions -- God dreams of all people groups knowing & loving Him! * * * Revelation 7:9, "After this I looked and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb." CHINA -- DAILY PRAYER GUIDE FOR ALL PEOPLE GROUPS & UNREACHED PEOPLE GROUPS Page 1 PRAY PEOPLE GROUP POPULATION % - PERCENT % - PERCENT LR: PRIMARY PRIMARY PHOTOS OF DAILY: NAME: IN CHINA: EVANGELICAL: CHRISTIAN: FR LANGUAGE: RELIGION: PEOPLE GROUPS: 1 Jan. A Che 42,000 0 0 FR Ache Ethnic Religions 2 Jan. A'ou 2,800 0 0 FR A'ou Ethnic Religions 3 Jan. A-Hmao 455,000 75% 80% Miao,LargeFlowery Christianity 4 Jan.