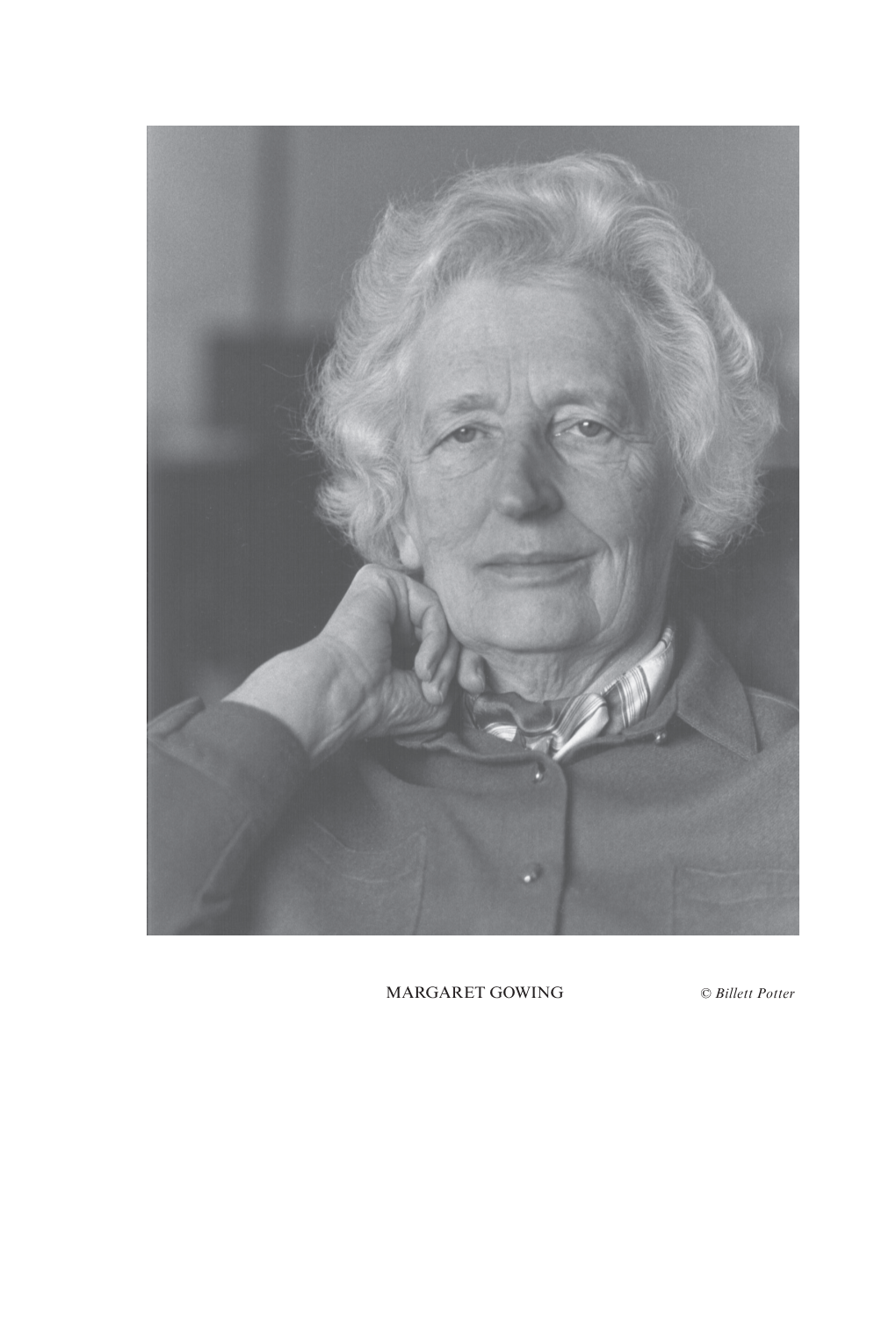

Margaret Mary Gowing1 1921–1998

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Price of Alliance: American Bases in Britain

/ THE PRICE OF ALLIANCE: AMERICAN BASES IN BRITAIN John Saville In 1984 there were 135 American military bases in Britain, most of them operational, some still being planned or built. This total was made up of 25 major operational bases or military headquarters, 35 minor or reserve bases, and 75 facilities used by the US Armed Forces. There were also about 30 housing sites for American personnel and their families. The term 'facility' covers a variety of different functions, and includes intelligence centres, stores, fuel supply points, aircraft weapon ranges and at least fourteen contingency military hospitals. Within this military complex there are five confirmed US nuclear weapon stores in the United Kingdom: at Lakenheath in East Anglia; Upper Heyford in Northampton- shire; Holy Loch and Machrihanish in south-west Scotland; and St. Mawgan in Cornwall. Other bases, notably Woodbridge and Alconbury, are thought to have storage facilities for peacetime nuclear weapons. All this information and much more, is provided in the only compre- hensive published survey of American military power in Britain. This is the volume by Duncan Campbell, The Unsinkable Aircraft Carrier. American Military Power in Britain, published by Michael Joseph in 1984. It is an astonishing story that Campbell unfolds, and the greater part of it-and certainly its significance for the future of the British people- has remained largely unknown or ignored by both politicians and public. The use of British bases by American planes in April 1986 provided the beginnings of a wider awareness of the extent to which the United Kingdom has become a forward operational base for the American Armed Forces within the global strategy laid down by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington; but it would be an exaggeration to believe that there is a general awareness, or unease of living in an arsenal of weapons controlled by an outside power. -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

Nuclear Scholars Initiative a Collection of Papers from the 2013 Nuclear Scholars Initiative

Nuclear Scholars Initiative A Collection of Papers from the 2013 Nuclear Scholars Initiative EDITOR Sarah Weiner JANUARY 2014 Nuclear Scholars Initiative A Collection of Papers from the 2013 Nuclear Scholars Initiative EDITOR Sarah Weiner AUTHORS Isabelle Anstey David K. Lartonoix Lee Aversano Adam Mount Jessica Bufford Mira Rapp-Hooper Nilsu Goren Alicia L. Swift Jana Honkova David Thomas Graham W. Jenkins Timothy J. Westmyer Phyllis Ko Craig J. Wiener Rizwan Ladha Lauren Wilson Jarret M. Lafl eur January 2014 ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK About CSIS For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars are developing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofi t or ga ni za tion headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affi liated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to fi nding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has become one of the world’s preeminent international institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global health and economic integration. Former U.S. senator Sam Nunn has chaired the CSIS Board of Trustees since 1999. -

Parnell and His Times Edited by Joep Leerssen Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49526-4 — Parnell and his Times Edited by Joep Leerssen Frontmatter More Information PARNELL AND HIS TIMES Marked by names such as W. B. Yeats, James Joyce, and Patrick Pearse, the decade – was a period of revolutionary change in Ireland, in literature, politics, and public opinion. What fed the creative and reformist urge besides the circumstances of the moment and a vision of the future? The leading experts in Irish history, literature, and culture assembled in this volume argue that the shadow of the past was also a driving factor: the traumatic, undi- gested memory of the defeat and death of the charismatic national leader Charles Stewart Parnell (–). The authors reassess Parnell’s impact on the Ireland of his time, its cultural, religious, political, and intellectual life, in order to trace his posthumous influence into the early twentieth century in fields such as political activism, memory culture, history-writing, and literature. is Professor of European Studies at the University of Amsterdam. His books Mere Irish and Fíor-Ghael () and Remembrance and Imagination () helped establish the specialism of Irish Studies. His comparative work on national (self-) stereotyp- ing and cultural nationalism earned him the Spinoza Prize in and the Madame de Staël Prize in . He is also the editor of the Encyclopedia of Romantic Nationalism in Europe (). © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49526-4 — Parnell and his Times Edited by Joep Leerssen Frontmatter More Information Parnell memorial by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (; obelisk designed by Henry Bacon), Parnell Square, Dublin. -

The Plutonium Business

WALTER C. PATTERSON for the Nuclear Control Institute The Plutonium Business and the Spread of the Bomb Granada Publishing 1 Paladin Books Granada Publishing Ltd 8 Grafton Street, London WIX MA Published by Paladin Books 1984 Copyright Nuclear Control Institute 1984 ISBN 0-586-08482-7 Reproduced, printed and bound in Great Britain by Hazell Watson & Viney Limited, Aylesbury, Bucks Set in Ehrhardt All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re- sold , hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Walter C. Patterson was born in Canada in 1936. He took a postgraduate degree in nuclear physics at the University of Manitoba. In 1960 he moved to Britain, where he became involved in environmental issues. He joined the staff of Friends of the Earth in London in 1972, was their energy specialist until 1978 and was their lead witness at the Windscale Inquiry. Since 1978 he has been an independent commentator and consultant, dealing with energy and nuclear policy issues. He is energy consultant to Friends of the Earth, and was a witness at the Sizewell Inquiry. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Unpublished Material Clarke, Sabine. ‘Experts, Empire and Development: Fundamental Research for the British Colonies, 1940–1960’. PhD dissertation, University of London, 2006. Heaton, Matthew M. ‘Stark Roving Mad: The Repatriation of Nigerian Mental Patients and the Global Construction of Mental Illness, 1906–1960’. PhD dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, 2008. Pietsch, Tamson. ‘“A Commonwealth of Learning?” Academic Networks and the British World, 1890–1940’. PhD dissertation, University of Oxford, 2009. Worboys, Michael. ‘Science and British Colonial Imperialism, 1895–1940’. PhD dissertation, University of Sussex, 1979. Published Material Alter, Peter. The Reluctant Patron: Science and the State in Britain 1850–1920. Oxford: Berg, 1987. Alvares, Claude. Science, Development and Violence. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1991. Anker, Peder. Imperial Ecology: Environmental Order in the British Empire, 1895–1945. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001. Armitage, David. The Ideological Origins of the British Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Arnold, David (ed.). Imperial Medicine and Indigenous Societies. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988. Arnold, David. Science, Technology and Medicine in Colonial India: The New Cambridge History of India, III, 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Ashton, S.R. and S. Stockwell. Imperial Policy and Colonial Practice, 1925–1945; British Documents on the End of Empire. London: HMSO, 1996. Aslanian, S. ‘Social Capital, “Trust” and the Role of Networks in Julfan Trade: Informal and Semi-formal Institutions at Work’. Journal of Global History 1 (2006): 383–402. Atkinson, Alan. ‘Time, Place and Paternalism: Early Conservative Thinking in New South Wales’. Australian Historical Studies 23 (1988): 1–18. Baber, Zaheer. The Science of Empire: Scientific Knowledge, Civilization, and Colonial Rule in India. -

Ernest Marsden's Nuclear New Zealand

Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, Vol. 139, p. 23–38, 2006 ISSN 0035-9173/06/010023–16 $4.00/1 Ernest Marsden’s Nuclear New Zealand: from Nuclear Reactors to Nuclear Disarmament rebecca priestley Abstract: Ernest Marsden was secretary of New Zealand’s Department of Scientific and Industrial Research from 1926 to 1947 and the Department’s scientific adviser in London from 1947 to 1954. Inspired by his early career in nuclear physics, Marsden had a post-war vision for a nuclear New Zealand, where scientists would create radioisotopes and conduct research on a local nuclear reactor, and industry would provide heavy water and uranium for use in the British nuclear energy and weapons programmes, with all these ventures powered by energy from nuclear power stations. During his retirement, however, Marsden conducted research into environmental radioactivity and the impact of radioactive bomb fallout and began to oppose the continued development and testing of nuclear weapons. It is ironic, given his early enthusiasm for all aspects of nuclear development, that through his later work and influence Marsden may have actually contributed to what we now call a ‘nuclear-free’ New Zealand. Keywords: Ernest Marsden, heavy water, nuclear, New Zealand INTRODUCTION to nuclear weapons development – which he was happy to support in the 1940s and 1950s In the 1990s, Ross Galbreath established Ernest – changed in his later years. By necessity this Marsden as having been the driving force be- article includes some material already covered hind the involvement of New Zealand scientists by Galbreath and Crawford but it also covers on the Manhattan and Montreal projects, the new ground. -

Mark Oliphant Frs and the Birmingham Proton Synchrotron

UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES SCHOOL OF HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY MARK OLIPHANT FRS AND THE BIRMINGHAM PROTON SYNCHROTRON A thesis submitted for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By David Ellyard B.Sc (Hons), Dip.Ed, M.Ed. December 2011 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. 20 December 2011 2 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. -

Historical Group

Historical Group NEWSLETTER and SUMMARY OF PAPERS No. 75 Winter 2019 Registered Charity No. 207890 COMMITTEE Chairman: Dr Peter J T Morris ! Dr Christopher J Cooksey (Watford, 5 Helford Way, Upminster, Essex RM14 1RJ ! Hertfordshire) Secretary: Prof. John W Nicholson !Prof Alan T Dronsfield (Swanwick, 52 Buckingham Road, Hampton, Middlesex, ! Dr John A Hudson (Cockermouth) TW12 3JG [e-mail: [email protected]] !Prof Frank James (Royal Institution) Membership Prof Bill P Griffith !Dr Michael Jewess (Harwell, Oxon) Secretary: Department of Chemistry, Imperial College, ! Dr Fred Parrett (Bromley, London) London, SW7 2AZ [e-mail: [email protected]] ! Prof Henry Rzepa (Imperial College) Treasurer: Prof Richard Buscall Exeter, Devon [e-mail: [email protected]] Newsletter Dr Anna Simmons Editor Epsom Lodge, La Grande Route de St Jean, St John, Jersey, JE3 4FL [e-mail: [email protected]] Newsletter Dr Gerry P Moss Production: School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS [e-mail: [email protected]] https://www.qmul.ac.uk/sbcs/rschg/ http://www.rsc.org/historical/ 1 Contents From the Editor (Anna Simmons) 2 Message from the Incoming Chair (Peter Morris) 3 ROYAL SOCIETY OF CHEMISTRY HISTORICAL GROUP MEETINGS 3 Celebrating the Centenary of IUPAC 3 Joint Meeting of the Institute of Physics History of Physics Group and the RSC Historical Group, Centenary of Transmutation 4 RSCHG NEWS 5 The Historical Group AGM (John Hudson)! ! 5! OBITUARIES 5 The Nearness of the Past: Remembering -

Atomic Assurance a Volume in the Series

Atomic Assurance a volume in the series Cornell Studies in Security Affairs Edited by Robert J. Art, Robert Jervis, and Stephen M. Walt A list of titles in this series is available at cornellpress . cornell . edu. Atomic Assurance The Alliance Politics of Nuclear Proliferation Alexander Lanoszka Cornell University Press Ithaca and London Copyright © 2018 by Cornell University The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. First published 2018 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of Amer i ca Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data Names: Lanoszka, Alexander, author. Title: Atomic assurance : the alliance politics of nuclear proliferation / Alexander Lanoszka. Description: Ithaca [New York] : Cornell University Press, 2018. | Series: Cornell studies in security affairs | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018016356 (print) | LCCN 2018017762 (ebook) | ISBN 9781501729195 (pdf) | ISBN 9781501729201 (ret) | ISBN 9781501729188 | ISBN 9781501729188 (cloth ; alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Nuclear nonproliferation— International cooperation. | Nuclear arms control— International cooperation. | Nuclear arms control—Government policy—United States. | Nuclear nonproliferation— Government policy—United States. | United States— Foreign relations—1945–1989— case studies. Classification: LCC JZ5675 (ebook) | LCC JZ5675 .L36 2018 (print) | DDC 327.1/747— dc23 LC rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2018016356 To my parents Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: The Alliance Politics of Nuclear Proliferation 1 1. -

Thesis Front 2

Nuclear New Zealand: New Zealandʼs nuclear and radiation history to 1987 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History and Philosophy of Science in the University of Canterbury by Rebecca Priestley, BSc (hons) University of Canterbury August 2010 Table of contents Abstract 1 Acknowledgements 2 Chapter 1 Nuclear-free New Zealand: Reality or a myth to be debunked? 3 Chapter 2 The radiation age: Rutherford, New Zealand and the new physics 25 Chapter 3 The public are mad on radium! Applications of the new science 45 Chapter 4 Some fool in a laboratory: The atom bomb and the dawn of the nuclear age 80 Chapter 5 Cold War and red hot science: The nuclear age comes to the Pacific 110 Chapter 6 Uranium fever! Uranium prospecting on the West Coast 146 Chapter 7 Thereʼs strontium-90 in my milk: Safety and public exposure to radiation 171 Chapter 8 Atoms for Peace: Nuclear science in New Zealand in the atomic age 200 Chapter 9 Nuclear decision: Plans for nuclear power 231 Chapter 10 Nuclear-free New Zealand: The forging of a new national identity 257 Chapter 11 A nuclear-free New Zealand? The ideal and the reality 292 Bibliography 298 1 Abstract New Zealand has a paradoxical relationship with nuclear science. We are as proud of Ernest Rutherford, known as the father of nuclear science, as of our nuclear-free status. Early enthusiasm for radium and X-rays in the first half of the twentieth century and euphoria in the 1950s about the discovery of uranium in a West Coast road cutting was countered by outrage at French nuclear testing in the Pacific and protests against visits from American nuclear-powered warships. -

REPORT the History of Science, Medicine and Technology at Oxford

Downloaded from http://rsnr.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on June 10, 2016 Notes Rec. R. Soc. (2006) 60, 69–83 doi:10.1098/rsnr.2005.0129 Published online 18 January 2006 REPORT The history of science, medicine and technology at Oxford Robert Fox*, Faculty of History, University of Oxford, Broad Street, Oxford OX1 3BD, UK The history of science came early to Oxford. Its first champion was Robert T. Gunther, the son of a keeper of zoology at the British Museum and a graduate of Magdalen College who took a first there in the School of Natural Science in 1892, specializing in zoology (figure 1). As tutor in natural science at Magdalen (and subsequently a fellow) from 1894 until his retirement in 1920, at the age of 50, Gunther showed himself to be a fighter, both for the cause of science in the university and for the preservation of Oxford’s scientific heritage. His first work, A history of the Daubeny Laboratory (1904), reflected his devotion to the memory of the laboratory’s founder and Magdalen’s greatest man of science, Charles Daubeny, who had held chairs of chemistry, botany and rural economy at various times, for long periods simultaneously, between 1822 and his death in 1867.1 Supplements, bearing the main title The Daubeny Laboratory register, followed in 1916 and 1924,2 but it was Gunther’s Early science in Oxford, published in 14 substantial volumes between 1920 and 1945, that signalled his definitive move from science to history.3 World War I brought home to Gunther the vulnerability of Oxford’s scientific collections, in particular the many early instruments that survived, largely disregarded, in the colleges.