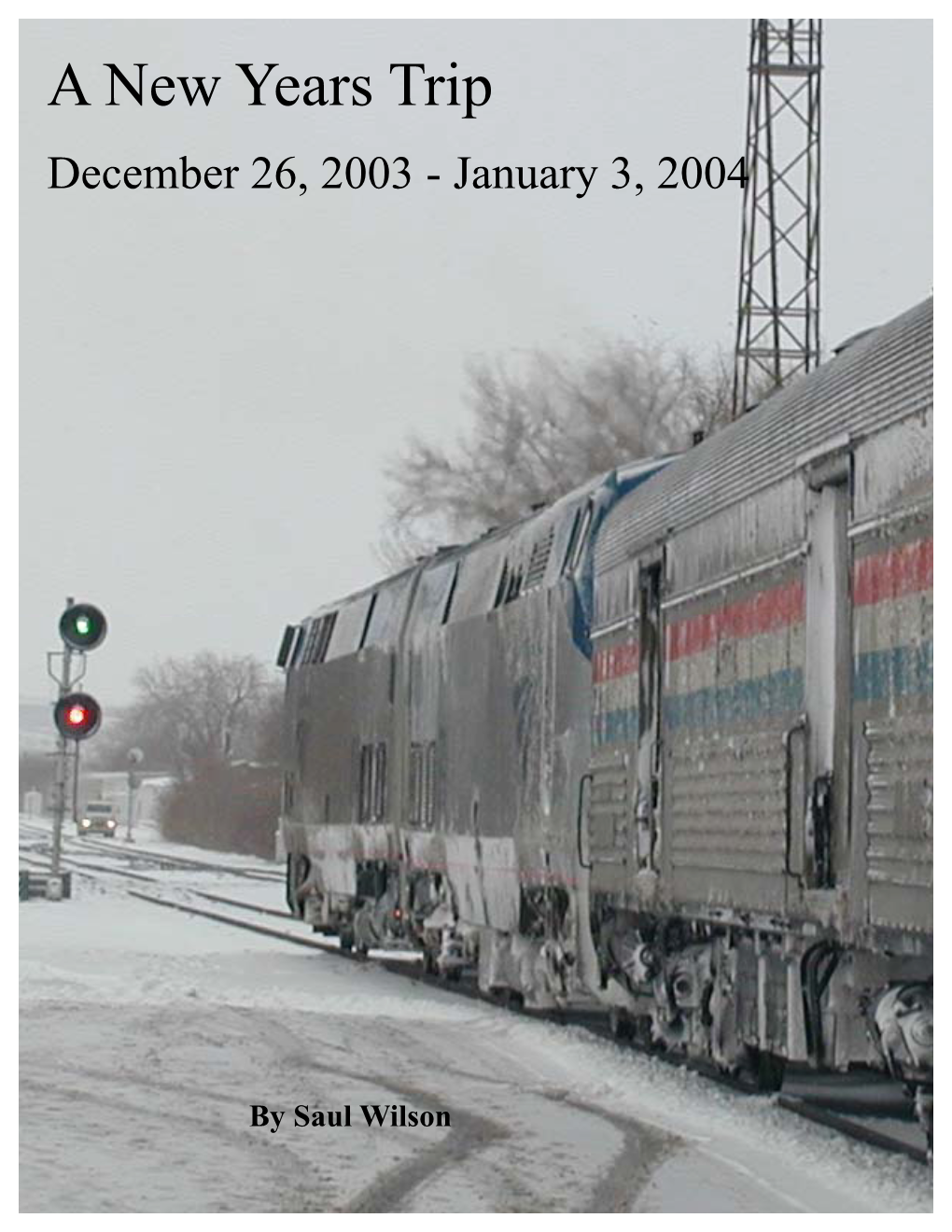

A New Years Tripa New Years Trip December 26, 2003 - January 3, 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Metropolitan Boston Transportation Commission

SENATE No. 686 Cfre Commontocalti) of egasgacbusettg % REPORT OF THE METROPOLITAN BOSTON TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION Created by Chapter 121 of the Resolves op 1957 January 1958 * BOSTON WRIGHT A POTTER PRINTING CO., LEGISLATIVE PRINTERS 32 DERNE STREET 1968 Cl')t CommoniuealtJ) ot spassacimsetts * RESOLVE OF AUTHORIZATION. [Chapter 121] Resolve providing for an investigati )N AND STUDY BY A SPECIAL COMMISSION RELATIVE TO THE CREATION OF A METE DPOLITAN RAPID TRANSIT COMMISSION TO STUDY THE EXTENSION OF RAPID TBANSI' ERVICE THROUGHOUT THE AREA SERVED BY THE METROPOLITAN TRANSIT AUTHO TY AND RELATIVE TO TRANSPORTATION FACILITIES IN THE BOSTON METROPOLI AN AREA Resolved, That an unpaid special comr ion to consist of two members of the senate to be designated by the president thereof, three members of the house of representatives to be designated by the ipeaker thereof, and two persons to be appointed by the governor, is hereby es stablished for the purpose of making an investigation and study of the subject mai tter of current house document numbered 862, relative to providing for the creationn of a metropolitan rapid transit commis- sion to study the extension of rapid transi?it service throughout the area now served by the metropolitan transit authority: and of the investigation proposed by em- rent house document numbered 1736. ulative to transportation facilities in the Boston metropolitan area. Said commission shallbe provided with quarters in the state house or elsewhere, and may expend for clerical and other services and expenses such sums as may be appropriated therefor. Said commission shall report to the general court the re- sults of its investigation and study, and its recommendations, if any, together with drafts of legislation necessary to carry said recommendations into effect, by filing the same with the clerk of the senate on or before the fourth Wednesday of January in the year nineteen hundred and fifty-eight. -

40Thanniv Ersary

Spring 2011 • $7 95 FSharing tihe exr periencste of Fastest railways past and present & rsary nive 40th An Things Were Not the Same after May 1, 1971 by George E. Kanary D-Day for Amtrak 5We certainly did not see Turboliners in regular service in Chicago before Amtrak. This train is In mid April, 1971, I was returning from headed for St. Louis in August 1977. —All photos by the author except as noted Seattle, Washington on my favorite train to the Pacific Northwest, the NORTH back into freight service or retire. The what I considered to be an inauspicious COAST LIMITED. For nearly 70 years, friendly stewardess-nurses would find other beginning to the new service. Even the the flagship train of the Northern Pacific employment. The locomotives and cars new name, AMTRAK, was a disappoint - RR, one of the oldest named trains in the would go into the AMTRAK fleet and be ment to me, since I preferred the classier country, had closely followed the route of dispersed country wide, some even winding sounding RAILPAX, which was eliminat - the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804, up running on the other side of the river on ed at nearly the last moment. and was definitely the super scenic way to the Milwaukee Road to the Twin Cities. In addition, wasn’t AMTRAK really Seattle and Portland. My first association That was only one example of the serv - being brought into existence to eliminate with the North Coast Limited dated to ices that would be lost with the advent of the passenger train in America? Didn’t 1948, when I took my first long distance AMTRAK on May 1, 1971. -

Bilevel Rail Car - Wikipedia

Bilevel rail car - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bilevel_rail_car Bilevel rail car The bilevel car (American English) or double-decker train (British English and Canadian English) is a type of rail car that has two levels of passenger accommodation, as opposed to one, increasing passenger capacity (in example cases of up to 57% per car).[1] In some countries such vehicles are commonly referred to as dostos, derived from the German Doppelstockwagen. The use of double-decker carriages, where feasible, can resolve capacity problems on a railway, avoiding other options which have an associated infrastructure cost such as longer trains (which require longer station Double-deck rail car operated by Agence métropolitaine de transport platforms), more trains per hour (which the signalling or safety in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The requirements may not allow) or adding extra tracks besides the existing Lucien-L'Allier station is in the back line. ground. Bilevel trains are claimed to be more energy efficient,[2] and may have a lower operating cost per passenger.[3] A bilevel car may carry about twice as many as a normal car, without requiring double the weight to pull or material to build. However, a bilevel train may take longer to exchange passengers at each station, since more people will enter and exit from each car. The increased dwell time makes them most popular on long-distance routes which make fewer stops (and may be popular with passengers for offering a better view).[1] Bilevel cars may not be usable in countries or older railway systems with Bombardier double-deck rail cars in low loading gauges. -

20210419 Amtrak Metrics Reporting

NATIONAL RAILROAD PASSENGER CORPORATION 30th Street Station Philadelphia, PA 19104 April 12, 2021 Mr. Michael Lestingi Director, Office of Policy and Planning Federal Railroad Administrator U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20590 Dear Mr. Lestingi: In accordance with the Metrics and Minimum Standards for Intercity Passenger Rail Service final rule published on November 16, 2020 (the “Final Rule”), this letter serves as Amtrak’s report to the Federal Railroad Administration that, as of April 10, 2021, Amtrak has provided the 29 host railroads over which Amtrak currently operates (listed in Appendix A) with ridership data for the prior month consistent with the Final Rule. The following data was provided to each host railroad: . the total number of passengers, by train and by day; . the station-specific number of detraining passengers, reported by host railroad whose railroad right-of-way serves the station, by train, and by day; and . the station-specific number of on-time passengers reported by host railroad whose railroad right- of-way serves the station, by train, and by day. Please let me know if you have any questions. Sincerely, Jim Blair Sr. Director, Host Railroads Amtrak cc: Dennis Newman Amtrak Jason Maga Amtrak Christopher Zappi Amtrak Yoel Weiss Amtrak Kristin Ferriter Federal Railroad Administration Mr. Michael Lestingi April 12, 2021 Page 2 Appendix A Host Railroads Provided with Amtrak Ridership Data Host Railroad1 Belt Railway Company of Chicago BNSF Railway Buckingham Branch Railroad -

Classic Trains' 2014-2015 Index

INDEX TO VOLUMES 15 and 16 All contents of publications indexed © 2013, 2014, and 2015 by Kalmbach Publishing Co., Waukesha, Wis. CLASSIC TRAINS Spring 2014 through Winter 2015 (8 issues) ALL ABOARD! (1 issue) 876 pages HOW TO USE THIS INDEX: Feature material has been indexed three or more times—once by the title under which it was published, again under the author’s last name, and finally under one or more of the subject categories or railroads. Photographs standing alone are indexed (usually by railroad), but photographs within a feature article are not separately indexed. Brief items are indexed under the appropriate railroad and/or category. Most references to people are indexed under the company with which they are commonly identified; if there is no common identification, they may be indexed under the person’s last name. Items from countries from other than the U.S. and Canada are indexed under the appropriate country name. ABBREVIATIONS: Sp = Spring Classic Trains, Su = Summer Classic Trains, Fa = Fall Classic Trains, Wi = Winter Classic Trains; AA! = All Aboard!; 14 = 2014, 15 = 2015. Albany & Northern: Strange Bedfellows, Wi14 32 A Bridgeboro Boogie, Fa15 60 21st Century Pullman, Classics Today, Su15 76 Abbey, Wallace W., obituary, Su14 9 Alco: Variety in the Valley, Sp14 68 About the BL2, Fa15 35 Catching the Sales Pitchers, Wi15 38 Amtrak’s GG1 That Might Have Been, Su15 28 Adams, Stuart: Finding FAs, Sp14 20 Anderson, Barry: Article by: Alexandria Steam Show, Fa14 36 Article by: Once Upon a Railway, Sp14 32 Algoma Central: Herding the Goats, Wi15 72 Biographical sketch, Sp14 6 Through the Wilderness on an RDC, AA! 50 Biographical sketch, Wi15 6 Adventures With SP Train 51, AA! 98 Tracks of the Black Bear, Fallen Flags Remembered, Wi14 16 Anderson, Richard J. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Dr. Benjamin Rush's Journal of a Trip to Carlisle in 1784 YOU know I love to be in the way of adding to my stock of ideas upon all subjects," Benjamin Rush observed to his wife in a letter of 1787. An insatiable gatherer and recorder of facts and observations, Rush kept journals throughout his life—some continuously over many years, like his Commonplace Books recently edited by Dr. George W. Corner as part of Rush's Autobiography; others for brief periods or for special purposes, like his "Quack Recipe Book" in the Library Company of Philadelphia, his Scottish journal in the Indiana University Library, and the present little diary of a journey from Philadelphia to Carlisle and return in April, 1784. This diary consists of twenty-three duodecimo pages stitched at one edge, and is written entirely in Rush's hand. Owned by a suc- cession of Rush's descendants, it at length came to light in the sale of the Alexander Biddle Papers at the Parke-Bernet Galleries in New York in 1943. (It will be found listed in the Biddle Sale Cata- logue, Part I, lot 219.) It was then purchased by the late Josiah C. Trent, M.D., of Durham, North Carolina, who, when he learned that the present writer was investigating Rush's part in the founding of Dickinson College at Carlisle, very kindly furnished a photostatic 443 444 L. H. BUTTERFIELD October copy of the 1784 journal, together with permission to use it in what- ever way seemed best. -

November/December 2020

Nov. – Dec. 2020 Issue Number 865 Editor’s Comments The next Membership meeting will be a virtual Zoom meeting at 7:30 p.m. Thursday, January 7. Inside This Issue If you know someone who wants to view the meeting, either a visiting railfan or an interested person, it is okay to pass the Editor’s Comments 1 link onto them (but please do not send to large groups). Inside This Issue 1 Watch for an email with meeting sign-in details. Club Officers 1 President’s Comments You will notice that this issue is a bit longer than our normal. 2 We decided that it was time to better coordinate the issue Amtrak News 2 month with the calendar, so this issue is a one-time combina- Pictures from Many of the CRRC Steam Trips 3-6 tion of two months of H & M. In January, we will return to our typical monthly issue of 16 pages. In the meantime, Virtual Railfanning in Time of COVID-19 7 please enjoy this month’s articles and its many photos. Santa Fe, Ohio? 8-9 Happy Holidays! Let’s all have a safe and happy New Year! A Visit to Kentucky Steam Heritage Corporation 10-15 Railfan’s Diary 16-21 Do you have thoughts and questions that you’d like to Steam News 22-27 share in future Headlight & Markers? Meeting Notice 28 Send electronic submissions to: [email protected] Perhaps you’ve thought of submitting an article or two --- now would be a great time to do so! Dave Puthoff Club Officers Club Email: [email protected]. -

Amtrak Cascades Fleet Management Plan

Amtrak Cascades Fleet Management Plan November 2017 Funding support from Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Information The material can be made available in an alternative format by emailing the Office of Equal Opportunity at [email protected] or by calling toll free, 855-362-4ADA (4232). Persons who are deaf or hard of hearing may make a request by calling the Washington State Relay at 711. Title VI Notice to Public It is the Washington State Department of Transportation’s (WSDOT) policy to assure that no person shall, on the grounds of race, color, national origin or sex, as provided by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise discriminated against under any of its federally funded programs and activities. Any person who believes his/her Title VI protection has been violated, may file a complaint with WSDOT’s Office of Equal Opportunity (OEO). For additional information regarding Title VI complaint procedures and/or information regarding our non-discrimination obligations, please contact OEO’s Title VI Coordinator at 360-705-7082. The Oregon Department of Transportation ensures compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; 49 CFR, Part 21; related statutes and regulations to the end that no person shall be excluded from participation in or be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance from the U.S. Department of Transportation on the grounds of race, color, sex, disability or national origin. -

Disneyland, 1955: Just Take the Santa Ana Freeway to the American Dream Author(S): Karal Ann Marling Reviewed Work(S): Source: American Art, Vol

Disneyland, 1955: Just Take the Santa Ana Freeway to the American Dream Author(s): Karal Ann Marling Reviewed work(s): Source: American Art, Vol. 5, No. 1/2 (Winter - Spring, 1991), pp. 168-207 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Smithsonian American Art Museum Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3109036 . Accessed: 06/12/2011 16:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Smithsonian American Art Museum are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Art. http://www.jstor.org Disneyland,1955 Just Takethe SantaAna Freewayto theAmerican Dream KaralAnn Marling The opening-or openings-of the new of the outsideworld. Some of the extra amusementpark in SouthernCalifornia "invitees"flashed counterfeit passes. did not go well. On 13 July, a Wednes- Othershad simplyclimbed the fence, day, the day of a privatethirtieth anniver- slippinginto the parkin behind-the-scene saryparty for Walt and Lil, Mrs. Disney spotswhere dense vegetation formed the herselfwas discoveredsweeping the deck backgroundfor a boat ride througha of the steamboatMark Twainas the first make-believeAmazon jungle. guestsarrived for a twilightshakedown Afterwards,they calledit "Black cruise.On Thursdayand Friday,during Sunday."Anything that could go wrong galapreopening tributes to Disney film did. -

W:\Data\DOT\Box 2\12245\12245D.Txt

Word Searchable Version not a True Copy National Transportation Library Section 508 and Accessibility Compliance The National Transportation Library (NTL) both links to and collects electronic documents in a variety of formats from a variety of sources. The NTL makes every effort to ensure that the documents it collects are accessible to all persons in accordance with Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act Amendments of 1998 (29 USC 794d), however, the NTL, as a library and digital repository, collects documents it does not create, and is not responsible for the content or form of documents created by third parties. Since June 21, 2001, all electronic documents developed, procured, maintained or used by the federal government are required to comply with the requirements of Section 508. If you encounter problems when accessing our collection, please let us know by writing to [email protected] or by contacting us at (800) 853- 1351. Telephone assistance is available 9AM to 6:30PM Eastern Time, 5 days a week (except Federal holidays). We will attempt to provide the information you need or, if possible, to help you obtain the information in an alternate format. Additionally, the NTL staff can provide assistance by reading documents, facilitate access to specialists with further technical information, and when requested, submit the documents or parts of documents for further conversion. Document Transcriptions In an effort to preserve and provide access to older documents, the NTL has chosen to selectively transcribe printed documents into electronic format. This has been achieved by making an OCR (optical character recognition) scan of a printed copy. -

ENOCK BROS'. Typewriter

fVEvV MIMSTERS" PRESEN A A Discovery That Hai tlte Appearance of TED. Double Murtlor. cofiiw China's New Minister mid Germany"* First N. 5..A discov¬ Amhanttnilor these MlDDLKTOWN, Y., Sept. Hefore the President, 'Oh, DiBcussion on the Thousands Subjeot May be ery of what has the appearance of a doublo Assemble to Witness Washington. after¬ Revolution nnd n Sept. 5..Yesterday murder, to be as¬ Next in Order, may prove triple Events. noon the conduct of the ense of China in sassination, has just been made at Bur- Yesterday's the negotiations over the law liughuin, at the foot of the exclusion In Shawangunk was ofUcially tukou Advertisements Eating A THOROUGH BEVISION PROBABLE. mountains. The events leading up to tho THE HALF MILE RECORD LOWERED of I has been murders date a little time charge by Yang brought about the supposed back. Yu, the new Chi¬ by Paul a who resides introduction of the A Ulli with Thin End in Holliday, widower, nese whose Cottolene, View Will bo near married a Tim Contest Ilctwecn II. C. of minister, Burliugbam, recently Wheeler, rank iu Iiis own Tire me." new vegetable The Ono of the Four to be Introduced When young woman wlio had been for tho National shortening. working Cycling Association of country is so high discovery of this and the the Homo Finally Adopt* Kb Rules. him. Soon after tho marriage Hollidny's anil product, house and barn America, J. W. Schoflnhl, Champion that it is only four demonstration of its remarkable Senator Cray's View«. were burned and his crip¬ of below that pled son was burned to death in the house. -

Pennvolume1.Pdf

PENNSYLVANIA STATION REDEVELOPMENT PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I: ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Executive Summary ............................................................... 1 ES.1 Introduction ................................................................ 1 ES.2 Purpose and Need for the Proposed Action ......................................... 2 ES.3 Alternatives Considered ....................................................... 2 ES.4 Environmental Impacts ....................................................... 3 ES.4.1 Rail Transportation .................................................... 3 ES.4.2 Vehicular and Pedestrian Traffic .......................................... 3 ES.4.3 Noise .............................................................. 4 ES.4.4 Vibration ........................................................... 4 ES.4.5 Air Quality .......................................................... 4 ES.4.6 Natural Environment ................................................... 4 ES.4.7 Land Use/Socioeconomics ............................................... 4 ES.4.8 Historic and Archeological Resources ...................................... 4 ES.4.9 Environmental Risk Sites ............................................... 5 ES.4.10 Energy/Utilities ...................................................... 5 ES.5 Conclusion Regarding Environmental Impact ...................................... 5 ES.6 Project Documentation Availability .............................................. 5 Chapter 1: Description