Watching the Cavalieri Della Montagna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messner:"L'alpinismo Inizia Dove Finisce Il Turismo" Marta Cassin Sulle Pareti Del Nonno

montagne360° la rivista del Club Alpino Italiano settembre 2012 del Club Alpino Italiano, n. - 9/2012 Sped. – in Post. 45% abb. art. 2 comma 20/b legge 662/96 - Filiale di Milano. Messner:"L'alpinismo inizia dove finisce il turismo" . Rivista mensile Marta Cassin sulle pareti del nonno Speleologia: viaggio dentro le grotte vulcaniche lA montAgnA settembre 2012 unIsCe all’imbrago editoriale ggancio Calz i per a ata er orizzonti e orientamenti orzat gono rinf mica ops co lo n tir ant e a ll-a rou nd co lle ga to a l s is te m a d i a l la c c ia t u r a Il nostro mondo in edicola Il numero di Montagne 360° che avete tra le mani è l’ultimo che sarà inviato solo ai Soci CAI. Da ottobre, infatti, la rivista sarà distribuita anche nelle edicole e sarà a disposizione – al prezzo di € 3,90 - di tutti gli appassionati di montagna, di ambiente, di ar- T a rampicata, di speleologia, di cultura alpina, di sicurezza e di tanti l lo n altri temi legati alle Terre Alte. L’obiettivo è dialogare con i tanti e co n frequentatori e amanti della montagna che (per ora) non sono c us nostri Soci. Ai nuovi lettori offriremo la nostra idea, il nostro ci ne modo di guardare alla montagna. Quell’idea che è tutta nell’Arti- tt o am colo 1 dello Statuto del Club Alpino Italiano, la cui forza e mo- m ort . dernità originale non si è mai indebolita nel corso dei 150 anni izz ta an un di storia del Sodalizio. -

Soccorso Alpino

ISSN 1590-7716 NOTIZIARIO MENSILE FEBBRAIO 2011 LA RIVISTA DEL CLUB ALPINO ITALIANO Scarpone SICUREZZA E COMFORT AD ALTA QUOTA Un UFO? No, è il nuovo, confortevole bivacco Gervasutti sul ghiacciaio di Fréboudze (2835 m) al Monte Bianco S.p.a – Sped.A.P. in – D. L. 353/03 (conv. in L. 27/02/04 n°46) art.Alpino Italiano - Lo 1 comma DCB Milano - La Rivista del Club In un fotomontaggio una contestualizzazione del nuovo bivacco Gervasutti del CAI Torino e una vista dall’interno. Ciò che colpisce è la proiezione verso il paesaggio: una novità per strutture di questo tipo, in genere assai povere di superfici finestrate. Numero 2 - Febbraio 2011 - Mensile - Poste Italiane 2011 - Mensile Poste Numero 2 - Febbraio UNICAI SOCIETÀ SOCCORSO ALPINO Nuova divisa Le escursioni Il CNSAS diventa per tutti “formato famiglia” Sezione nazionale i titolati della SAT del Club alpino Statistiche Il CAI al tempo della crisi Cresce la richiesta di socialità ull’aumento degli iscritti al CAI, che territoriale, vice presi- grande pubblico con il ritor- alla fine del 2010 hanno raggiunto la dente della Sezione di no del termalismo e il boom quota record di 319.056 soci contro i Torino, che nel 2008 è dei resort di benessere, con S315.032 del 2009 (LS 12/2010), è pos- stato tra i relatori al strutture iperboliche in sibile compiere una prima riflessione in Congresso nazionale di mezzo alle montagne, e con attesa di un’analisi approfondita che certa- Predazzo del Club Alpino la reinvenzione, a partire mente emergerà dal rapporto annuale. Più Italiano. -

Trento Film Festival 2017, Programma Completo

2018 I giovani raccontano la montagna Percorri i sentieri delle tue emozioni “Montagnav(v)entura” 11-15: scrivi un racconto come a te piace e mandacelo! “Montagnav(v)entura” 16-26: scegli un genere letterario tra umorismo, fantasy, r@cconto; scrivi un racconto lungo tra i 6000 e i 9000 caratteri e inviacelo. Leggi bene il regolamento completo, lo trovi sul sito www.premioitas.it www.facebook.com/Montagnavventura [email protected] I LUOGHI DEL FESTIVAL AUDITORIUM SANTA CHIARA Via Santa Croce, 67 CAFÈ DE LA PAIX - Passaggio Teatro Osele AULA KESSLER, DIPARTIMENTO DI SOCIOLOGIA E RICERCA SOCIALE - Via Verdi, 26 BOTTEGA MANDACARÙ - Piazza Fiera, 23 CASA DELLA SAT - Via Giannantonio Manci, 57 CASA ITAS - Piazza delle Donne Lavoratrici, 2 Quartiere Le Albere CASTELLO DEL BUONCONSIGLIO Via Bernardo Clesio, 5 CFSI - CENTRO PER LA FORMAZIONE ALLA SOLIDARIETÀ INTERNAZIONALE Vicolo San Marco, 1 DIPARTIMENTO DI LETTERE E FILOSOFIA Aula 7 - Via Tommaso Gar, 14 GALLERIE DI PIEDICASTELLO Piazza Piedicastello IMPACT HUB - Via Sanseverino, 95 LOACKER POINT - Piazza Fiera, 13 MALGONE DI CANDRIAI - Candriai MONDADORI BOOKSTORE - Via S. Pietro, 19 MONTAGNALIBRI - Piazza Fiera MULTISALA G.MODENA Via Francesco d’Assisi, 6 MUSE - Corso del Lavoro e della Scienza, 3 PALAZZO DELLE ALBERE, Via Roberto da Sanseverino PALAZZO LODRON - Piazza Lodron Festival per tutti i gusti! PALAZZO ROCCABRUNA - Via Santa Trinità, 24 LA COLAZIONE E LA MERENDA PALAZZO TRENTINI - Via Giannantonio Manci, 27 Via T. Gar DEL FESTIVAL - Piazza Fiera, 13 PARCO DEI MESTIERI Loacker Store Via San Giovanni Bosco, 1 IL PANINO GOURMET - Piazza DEL Garzetti, FESTIVAL 4 PIAZZA SANTA MARIA MAGGIORE Uva e Menta - Largo Carducci, 55 Il posto di Ste - Piazza Vittoria, 1 SALA CONFERENZE DELLA FONDAZIONE Gusto Giusto BRUNO KESSLER, Via Santa Croce, 77 BAR E RISTORANTE SALA CONFERENZE DELLA FONDAZIONE con piatti tipici- Cortile trentini Centro S. -

Volumi Biblioteca 2020

Volumi inseriti in biblioteca nel 2020 Valli di Lanzo – Le più belle ascensioni classiche e moderne Questo volume edito da Marco Blatto, è stato presentato sabato 5 settembre 2020 a Forno Alpi Graie nell’ambito della manifestazione “Val Grande verticale”. Il libro racchiude tantissime ascensioni relative alle Valli di Lanzo. SOCCORSO su ROCCIA – Tecniche di Base Scuola Nazionale Tecnici Soccorso Alpino Dalla Scuola Nazionale Tecnici Soccorso Alpino, un manuale che descrive le tecniche base di soccorso. Dai nodi alle tecniche di recupero, tutte illustrate con fotografie che ne descrivono i vari passaggi. Uno strumento di lavoro indispensabile per i tecnici del CNSAS ma anche uno strumento destinato a tutti gli alpinisti e frequentatori della montagna L´arte di essere libero Voytek Kurtyka è uno dei più grandi alpinisti di tutti i tempi. Nato nel 1947, è stato uno dei protagonisti dell'età d'oro dell'alpinismo himalayano: un periodo - gli anni 70 e 80 - che ha ridefinito lo stile di scalata sulle grandi montagne dell'Himalaya. Formato sulle mitologiche montagne dei Tatra, il suo approccio visionario verso lo stile alpino sulle grandi montagne della Terra lo ha portato a realizzare ascensioni straordinarie che occupano una posizione di primo piano nella storia dell'alpinismo. Si pensi alla salita della parete ovest del Gasherbrum IV, la "parete lucente", considerata l'ascensione più incredibile di sempre. Come lui, i suoi compagni di cordata - Jerzy Kukuczka, Erhard Loretan, Alex Maclntyre, John Porter e Robert Schauer - erano i miti di quegli anni. Di carattere schivo e riservato, Kurtyka ha declinato per vent'anni innumerevoli inviti ad apparizioni pubbliche e interviste, creando attorno a sé un alone di mistero che ha accresciuto il suo mito. -

Club Alpino Italiano Catalogo Monografie Per Autori UGET Torino

Club Alpino Italiano UGET Torino Biblioteca Catalogo Monografie per Autori Pagina 1 di 74 Biblioteca Cai UGET Torino Abbate , Paolo 1307 Alverà , Sandro 953 Gran Sasso d’Italia / Luca Grazzini. - : , . - ; cm 40 anni di prime salite e soccorsi in montagna degli ** 1. Collana “Guida ai monti d’Italia” 2. Gran Sasso 3. scoiattoli di Cortina / Carlo Gandini. - : , . - ; cm Parco Abruzzo ** 1. Associazioni sportive 2. Soccorso Alpino 3. Cortina d'Ampezzo Acconci , Donatella 444 Cadranno le case dei villaggi / Donatella Acconci . - : , Amateis , Dario 1653 . - ; cm Nuova guida scialpinistica del Canavese / Dario Amateis ** 1. Baite 2. Usi e costumi . - : , . - ; cm ** 1. Scialpinismo 2. Canavese Acutis , Pensiero 345 Dal monte Soglio alle Levanne / Pensiero Acutis . - : , Amin , Mohamed 766 . - ; cm Attraverso il Pakistan / Mohamed Amin . - : , . - ; cm ** 1. Trekking - Guide 2. Alpi Graie ** 1. Viaggi - Diari e memorie 2. Pakistan Affentranger, Irene 172 Amman , Olga 665 Picchi, colli e ghiacciai / Irene Affentranger. - : , . - ; cm Nella terra degli dei / Olga Amman . - : , . - ; cm ** 1. Letteratura - Antologie ** 1. Ascensioni – Europa extra Alpi Affentranger, Irene 1029 Amourous , Charles 292 Pista (la) illuminata / Irene Affentranger. - : , . - ; cm La Haute Maurienne / P. Dompnier. - : , . - ; cm ** 1. Letteratura narrativa ** 1. Guide (libri) 2. Alpi Cozie settentrionali Agnolotti , Giuseppe 423 Amy , Bernard 259 Sarmiento inferno bianco / Giuseppe Agnolotti . - : , . - Les montagnes des autres / Bernard Amy . - : , . - ; cm ; cm ** ** 1. Spedizioni extraeuropee 2. Spedizioni scientifiche 3. Ande 4. Patagonia Amy , Bernard 877 Gli alpinismi: idee forme tecniche / Bernard Amy . - : , Aiely , P. 1518 . - ; cm Escalades dans les Calanques: Marseille Veyre, Vallon ** 1. Alpinismo - Manuali des Aiguilles / P. Aiely . - : , . - ; cm ** 1. Arrampicata palestre 2. Calanques 3. Prealpi di Amy , Bernard 1514 Provenza Guide des escalades de la montagne Sainte Victorie v. -

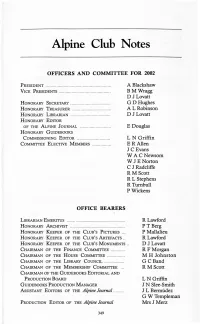

Alpine Club Notes

Alpine Club Notes OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 2002 PRESIDENT .. A Blackshaw VICE PRESIDENTS . BMWragg DJ Lovatt HONORARY SECRETARY . GD Hughes HONORARY TREASURER .. AL Robinson HONORARY LIBRARIAN .. D JLovatt HONORARY EDITOR OF THE ALPINE JOURNAL .. E Douglas HONORARY GUIDEBOOKS COMMISSIONING EDITOR . LN Griffin COMMITTEE ELECTIVE MEMBERS .. E RAllen JC Evans W ACNewsom W JE Norton CJ Radcliffe RM Scott RL Stephens R Tumbull P Wickens OFFICE BEARERS LIBRARIAN EMERITUS .. RLawford HONORARY ARCHIVIST .. .. PT Berg HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S PICTURES . P Mallalieu HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S ARTEFACTS .. RLawford HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S MONUMENTS .. DJ Lovatt CHAIRMAN OF THE FINANCE COMMITTEE RFMorgan CHAIRMAN OF THE HOUSE COMMITTEE .. MH Johnston CHAIRMAN OF THE LIBRARY COUNCIL .. GCBand CHAIRMAN OF THE MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE RM Scott CHAIRMAN OF THE GUIDEBOOKS EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION BOARD LN Griffin GUIDEBOOKS PRODUCTION MANAGER JN Slee-Smith ASSISTANT EDITORS OF THE Alpine Journal JL Bermudez GW Templeman PRODUCTION EDITOR OF THE Alpine Journal Mrs JMerz 349 350 THE ALPINE J OURN AL 2002 ASSISTANT HONORARY SECRETARIES: ANNuAL WINTER DINNER . MHJohnston LECTURES .. MWHDay MEETS . JC Evans MEMBERSHIP . RM Scot! TRUSTEES .. MFBaker JG RHarding S NBeare HONORARY SOLICITOR . PG C Sanders AUDITORS . PKF ASSISTANT SECRETARY (ADMINISTRATION) .. Sheila Harrison ALPINE CLIMBING GROUP PRESIDENT .. D Wilkinson HONORARY SECRETARY . RA Ruddle GENERAL, INFORMAL, AND CLIMBING MEETINGS 2001 9 January General Meeting: Stevan Jackson, British -

Letture Sull'alpinismo

CLUB ALPINO ITALIANO SEZIONE DI BOFFALORA SOPRA TICINO Per Passione Cenni di storia dell’alpinismo attraverso il contesto culturale, l’attrezzatura, le esigenze Boffalora Sopra Ticino presso la sede del Cai sabato 30 aprile 2011 ore 21.00 victoryproject.net Per Passione Cenni di storia dell’alpinismo attraverso il contesto culturale, l’attrezzatura, le esigenze di Lorenzo Merlo NN – Una storia (quasi) senza nomi Introduzione La storia siamo noi. Un luogo comune. Una verità A quelli che sono falliti nelle loro grandi aspirazioni, Ai macchinisti calmi e fedeli - ai viaggiatori ardenti troppo - ai piloti sui loro vascelli, A più d’un nobile canto o dipinto non riconosciuto - un monumento vorrei innalzare, coperto d’alloro, Alto, ben alto su tutto - A quanti vennero anzi tempo rapiti, Da qualche strano spirito di fuoco posseduti, Spenti da morte precoce. Walt Whitman Chiedendo rispettose scuse agli uomini noti e non, alle scuole dimenticate, agli alpinismi lon- tani dalle Alpi, alle montagne, pareti e vie mai prese in considerazione in questa storia dell’al- pinismo e dalle Storie dell’Alpinismo, proviamo ad evidenziare quanto i contesti, le contingen- ze, le esigenze e i materiali hanno impedito o concesso agli uomini che le stavano percorrendo e utilizzando. “Le montagne si scalano perché esistono” (Mallory), è solo una tra le diverse formule che tentano di spiegare l’alpinismo come motto umano. Senza le montagne, nessun alpinismo è possibile. Con le montagne, qualunque uomo è alpinista. Le storie che conosciamo sono – giusta- mente – alpicentriche. Gli altri alpinismi si sono afermati dopo quello alpino pro- priamente detto. Proprio per lo scarto temporale e per i diversi contesti culturali, una sorta di alpicentrismo ha soggiogato le storie dell’alpinismo che conosciamo. -

Biblioteca CAI

Inventario Segnatura Autore Titolo Casa Editrice Anno *Rassegna *internazionale *6. Rassegna internazionale dell'editoria di montagna : [S. l. : s. n.], 1992 dell'*editoria di *montagna <6. ; mostra di libri sulla montagna, le novità 1991-1992 : mostra stampa 1992 1992 ; Trento> di riviste di montagna : Trento, Centro S. Chiara, 13 aprile-3 (Trento : maggio 1992 Grafiche PZZ00017587 CAI AVB 016.91 RAS Artigianelli) Frassati, Luciana La *piccozza di Pier Giorgio / Luciana Frassati Torino : Società 2000 editrice internazionale, stampa 1995 PZZ00017539 CAI AVB 271 FRA Bhaktivedanta Swami, A. C. *Viaggio alla scoperta del sè / sua divina grazia Tavernelle Val di 2003 A.C.Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Pesa : The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, PZZ00017615 CAI AVB 294.5 BHA c2003 La *Bhagavad-gita cosÃ- com'è / con testo sanscrito Firenze : The 1998 originale, traslitterazione in caratteri romani, traduzione Bhaktivedanta letterale, traduzione letteraria e spiegazioni di A. C. book trust, PZZ00017616 CAI AVB 294.5 BHA Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada c1998 *Ecologia : un sos dalla natura / [a cura di Mario Palmieri] Milano : 1974 Selezione dal Reader's digest, PZZ00017677 CAI AVB 304.2 ECO 1974 Calvi, Giacomo *Alta Valle Brembana, un palmo di terra : una valle, una [S. l.] : 1988 storia, il formai de mut / racconto di: Giacomo Calvi ; Consorzio tutela racconto fotografico: Gio. Lodovico Baglioni ; matite: Renata formai de mut, PZZ00017455 CAI AVB 305.5 CAL Besola 1988 Belotti, Giuseppe *Ricordo del senatore Cristoforo Pezzini pioniere e primo Bergamo -

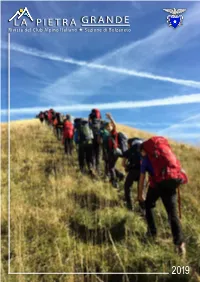

Pietragrande La

LA PIETRA GRANDE Rivista del Club Alpino Italiano « Sezione di Bolzaneto 2019 LA PIETRA GRANDE RIVISTA DEL CLUB ALPINO ITALIANO Sezione di BOLZANETO Via C. Reta 16r - Tel. e Fax 010.740.61.04 - 16162 Genova Da Bologna a Santiago de Compostela....50 www.caibolzaneto.it - [email protected] di Giorgio Trotter Apertura Sede e tesseramento: giovedì ore 21 Api e Vale sull’Alta Via dei Monti Liguri.....52 di Franco Api e Valentina Vinci Un’esperienza di vita...............................54 LA PIETRA GRANDE Rivista del Club Alpino Italiano « Sezione di Bolzaneto di Stefano Camarda Cos’è Alvi Trail?.........................................56 Sommario di Marzia Gelai Capodanno in solitaria notturna..............57 di Marco Ferrando Trek in Portogallo dalla A alla Z...............60 CAI SEZIONE di BOLZANETO.......................2 di Sabrina Poggi e Michela Repetto Il socio agente del corretto rapporto con la Sulla Cima di Nasta..................................64 montagna.................................................3 di Bruna Carrossino di Nadia Benzi CULTURA.............................................68 Anno XII • Numero 12 2019 ALPINISMO.........................................5 Monte Carmo, storia di una croce di La Montagna si sconta... salendo..............5 vetta......................................................68 di Salvatore Gabbe Gargioni di Pietro Pitter Guglieri In copertina: “Verso il blu” 1...8 e 1…9 ma l’Alpinismo non dà i 25 aprile sull’Antola per ricordare Guido Foto di Valentina Vinci numeri!.......................................................7 -

Annuario 2017

annuario CLUB ALPINO ITALIANO SEZIONE DI VARESE 2017 CLUB ALPINO ITALIANO SEZIONE DI VARESE CLUB ALPINO ITALIANO annuario 2017 Annuario 2017 SOMMARIO Pubblicazione di Cultura Montana CLUB ALPINO ITALIANO 02 Relazione del Presidente SEZIONE DI VARESE 04 Titolati e sezionali 2017 21100 VARESE 06 Cariche e incarichi anno 2017 Via Speri della Chiesa Jemoli, 12 Tel. e Fax 0332 289267 07 Cariche e collegamenti presso organismi regionali e nazionali Anno di costituzione 1906 Relazioni e-mail: 09 Scuola di alpinismo e sci-alpinismo “Remo e Renzo Minazzi” – CAI Varese [email protected] 18 Incontri di avvicinamento alla montagna sito web: 23 Gruppo escursionismo www.caivarese.it 30 Relazione gite sciistiche e corso sci discesa Iscritto Registro Operatori 32 Gruppo senior comunicazione n. 22832 37 Gruppo speleologico 41 Incontri di avvicinamento al cicloescursionismo in MTB Comitato di Redazione 49 Alpinismo giovanile 53 Attività culturale Paolo Belloni 55 Ginnastica presciistica Daniela Girola Pietro Macchi 56 Il “Gruppo Sentieri” del CAI Varese Edoardo Tettamanzi Pier Luigi Zanetti Uomini e montagne 59 Ricordo di Laura Roella Bramanti 60 Dedicato ad Attilio Faré Impaginazione e stampa 61 Mount Denali 6190 m Artestampa srl 65 Il “nostro” Eiger Galliate Lombardo, Varese 70 Incontro con Alessandro Gogna 77 In ricordo di un amico, Gino Buscaini Tutto il materiale qui riprodotto 78 L’orso – Tra Val Canali e San Polo di Piave (scritti, fotografie e disegni) è di proprietà 81 La strada per Gressoney… tra realtà, ricordi e fantasia della Sezione di Varese del Cai. 86 La Weissmies (4017 m) da Monza Prima di essere utilizzato per altre pubblicazioni è indispensabile 89 Il Sacro Monte e il Campo dei Fiori ci sono sempre l’autorizzazione della Sezione stessa. -

Programma TFF-2019.Pdf

DOMENICA 5 MAGGIO ORE 18.30 PRESENTAZIONE PUBBLICA VINCITORI EDIZIONE 2019 SALA CARITRO - Via G. Garibaldi 33 PATROCINI PARTNER Associato a Con il patrocinio di SOCI facebook.com/Montagnavventura 0461.891974 | 693 [email protected] www.premioitas.it DIREZIONE BORGO VALSUGANA 60 min I LUOGHI DEL FESTIVAL AREA ARCHEOLOGICA DI PALAZZO LODRON Piazza Lodron AUDITORIUM SANTA CHIARA Teatro e Atrio, Via Santa Croce, 67 BISTROT TRENTO ALTA Str. Alla Funivia, 15, Sardagna BOTTEGA MANDACARÙ - Piazza Fiera 23 CASA DELLA SAT Spazio Alpino, Via Giannantonio Manci, 57 AUDITORIUM CCI - Centro per la Cooperazione SANTA CHIARA Internazionale, Vicolo San Marco, 1 FEDERAZIONE TRENTINA PRO LOCO E LORO CONSORZI - Via Oss Mazzurana 8 FONDAZIONE CASSA DI RISPARMIO DI TRENTO E ROVERETO - Sala Conferenze, Via Giuseppe Garibaldi, 33 GIARDINO BOTANICO ALPINO VIOTE - Località Viote Internazionale - Vicolo San Marco, 1 MULTISALA G. MODENA Via Francesca D’Assisi, 6 MUSE - Corso del Lavoro e della Scienza 3 PALAGHIACCIO - Via Fersina, 15 PALAZZO DELLE ALBERE Via Roberto da Sanseverino PALAZZO GEREMIA - Via Belenzani 20 PALAZZO ROCCABRUNA - Via Santa Trinità, 24 PALAZZO THUN – CORTILE Via Rodolfo Belenzani, 19 38122 Trento TN PALAZZO TRENTINI - Via Giannantonio Manci, 27 PARCO DEI MESTIERI - Via San Giovanni Bosco, 1 PIAZZA DANTE PIAZZA DI PIEDICASTELLO - (Doss Trento) PIAZZA DUOMO RIFUGIO MODERNO DELLA SCIENZA Piazza Lodron SALA DELLA FILARMONICA Festival per tutti i gusti! Via Giuseppe Verdi, 30 CAMPO BASE QUARTIERE SOSAT - Via Malpaga, 17 servizio bar-ristorante, -

Vieni C Ti Farò E Scend Le Parol

Vieni con me, ti farò salire e scendere tra le parole della vita. Premio Itas Foto di Simone Falso dal film “LA PRIMA NEVE” www.premioitas.it EVENTI, INCONTRI, MOSTRE EVENTS, MEETINGS, EXHIBITIONS GIOVEDÌ THURSDAY 24.04 11.00 A seguire INAUGURAZIONE MOSTRA PRESENTAZIONE DEL VOLUME LALLA RAMAZZOTTI LA TRAVERSATA DELLE ALPI. MORASSUTTI. DOLOMITI DA THONON A TRENTO A cura di Valentina Morassutti e di Carlo di Douglas William Freshfield (1845- Marcello Conti. 1934). Prima edizione italiana, a cura di In collaborazione con Fondazione Dolomiti Itinera Alpina, del volume "Across country Unesco. from Thonon to Trento", diario della tra- Palazzo Trentini, Via Manci, 27 versata da Thonon sul Lago di Ginevra a Trento, compiuta tra luglio e agosto 1864. First Italian edition, edited by Itinera 17.00 Alpina, of the volume "Across country INAUGURAZIONE MOSTRA from Thonon to Trent", the diary of a trek CENTOCINQUANTA: across the Alps from Thonon on Lake Ge- neva to Trento in July and August 1864. 1864-2014, LA NASCITA Casa della SAT, via Manci, 57 DELL'ALPINISMO IN TRENTINO Un’iniziativa di Società degli Alpinisti Tridentini-Biblioteca della Montagna, 18.00 Trento Film Festival e Fondazione Acca- PRIMa a… ROCCABRUNA demia della Montagna del Trentino. Inaugurazione Trento Film Festival A cura di Marco Benedetti, Roberto e inaugurazione Mostra Bombarda, Riccardo Decarli e Fabrizio SPARTITI DELLE MONTAGNE. APERTURA MONTAGNALIBRI Torchio. COPERTINE DI MUSICA 28ª RASSEGNA e riviste sulla montagna. INTERNAZIONALE The exhibition brings together and dis- A cura del Museo nazionale della monta- plays the most recently published in- gna di Torino e della Camera di Commercio DELL’EDITORIA DI MONTAGNA ternational books and magazines on the I.A.A di Trento.