A Language on the Back Foot. the Afrikaans Lexicographer's Dilemma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

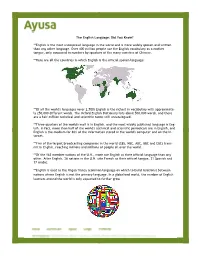

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

Language, Culture, and National Identity

Language, Culture, and National Identity BY ERIC HOBSBAWM LANGUAGE, culture, and national identity is the ·title of my pa per, but its central subject is the situation of languages in cul tures, written or spoken languages still being the main medium of these. More specifically, my subject is "multiculturalism" in sofar as this depends on language. "Nations" come into it, since in the states in which we all live political decisions about how and where languages are used for public purposes (for example, in schools) are crucial. And these states are today commonly iden tified with "nations" as in the term United Nations. This is a dan gerous confusion. So let me begin with a few words about it. Since there are hardly any colonies left, practically all of us today live in independent and sovereign states. With the rarest exceptions, even exiles and refugees live in states, though not their own. It is fairly easy to get agreement about what constitutes such a state, at any rate the modern model of it, which has become the template for all new independent political entities since the late eighteenth century. It is a territory, preferably coherent and demarcated by frontier lines from its neighbors, within which all citizens without exception come under the exclusive rule of the territorial government and the rules under which it operates. Against this there is no appeal, except by authoritarian of that government; for even the superiority of European Community law over national law was established only by the decision of the constituent SOCIAL RESEARCH, Vol. -

Dialects, Standards, and Vernaculars

1 Dialects, Standards, and Vernaculars Most of us have had the experience of sitting in a public place and eavesdropping on conversations taking place around the United States. We pretend to be preoccupied, but we can’t seem to help listening. And we form impressions of speakers based not only on the topic of conversation, but on how people are discussing it. In fact, there’s a good chance that the most critical part of our impression comes from how people talk rather than what they are talking about. We judge people’s regional background, social stat us, ethnicity, and a host of other social and personal traits based simply on the kind of language they are using. We may have similar kinds of reactions in telephone conversations, as we try to associate a set of characteristics with an unidentified speaker in order to make claims such as, “It sounds like a salesperson of some type” or “It sounds like the auto mechanic.” In fact, it is surprising how little conversation it takes to draw conclusions about a speaker’s background – a sentence, a phrase, or even a word is often enough to trigger a regional, social, or ethnic classification. Video: What an accent does Assessments of a complex set of social characteristics and personality traits based on language differences are as inevitable as the kinds of judgments we make when we find out where people live, what their occupations are, where they went to school, and who their friends are. Language differences, in fact, may serve as the single most reliable indicator of social position in our society. -

The Standardisation of African Languages Michel Lafon, Vic Webb

The Standardisation of African Languages Michel Lafon, Vic Webb To cite this version: Michel Lafon, Vic Webb. The Standardisation of African Languages. Michel Lafon; Vic Webb. IFAS, pp.141, 2008, Nouveaux Cahiers de l’Ifas, Aurelia Wa Kabwe Segatti. halshs-00449090 HAL Id: halshs-00449090 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00449090 Submitted on 20 Jan 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Standardisation of African Languages Language political realities CentRePoL and IFAS Proceedings of a CentRePoL workshop held at University of Pretoria on March 29, 2007, supported by the French Institute for Southern Africa Michel Lafon (LLACAN-CNRS) & Vic Webb (CentRePoL) Compilers/ Editors CentRePoL wishes to express its appreciation to the following: Dr. Aurelia Wa Kabwe-Segatti, Research Director, IFAS, Johannesburg, for her professional and material support; PanSALB, for their support over the past two years for CentRePoL’s standardisation project; The University of Pretoria, for the use of their facilities. Les Nouveaux Cahiers de l’IFAS/ IFAS Working Paper Series is a series of occasional working papers, dedicated to disseminating research in the social and human sciences on Southern Africa. -

Prioritizing African Languages: Challenges to Macro-Level Planning for Resourcing and Capacity Building

Prioritizing African Languages: Challenges to macro-level planning for resourcing and capacity building Tristan M. Purvis Christopher R. Green Gregory K. Iverson University of Maryland Center for Advanced Study of Language Abstract This paper addresses key considerations and challenges involved in the process of prioritizing languages in an area of high linguistic di- versity like Africa alongside other world regions. The paper identifies general considerations that must be taken into account in this process and reviews the placement of African languages on priority lists over the years and across different agencies and organizations. An outline of factors is presented that is used when organizing resources and planning research on African languages that categorizes major or crit- ical languages within a framework that allows for broad coverage of the full linguistic diversity of the continent. Keywords: language prioritization, African languages, capacity building, language diversity, language documentation When building language capacity on an individual or localized level, the question of which languages matter most is relatively less complicated than it is for those planning and providing for language capabilities at the macro level. An American anthropology student working with Sierra Leonean refugees in Forecariah, Guinea, for ex- ample, will likely know how to address and balance needs for lan- guage skills in French, Susu, Krio, and a set of other languages such as Temne and Mandinka. An education official or activist in Mwanza, Tanzania, will be concerned primarily with English, Swahili, and Su- kuma. An administrator of a grant program for Less Commonly Taught Languages, or LCTLs, or a newly appointed language authori- ty for the United States Department of Education, Department of Commerce, or U.S. -

Alexander's Empire

4 Alexander’s Empire MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES EMPIRE BUILDING Alexander the Alexander’s empire extended • Philip II •Alexander Great conquered Persia and Egypt across an area that today consists •Macedonia the Great and extended his empire to the of many nations and diverse • Darius III Indus River in northwest India. cultures. SETTING THE STAGE The Peloponnesian War severely weakened several Greek city-states. This caused a rapid decline in their military and economic power. In the nearby kingdom of Macedonia, King Philip II took note. Philip dreamed of taking control of Greece and then moving against Persia to seize its vast wealth. Philip also hoped to avenge the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 B.C. TAKING NOTES Philip Builds Macedonian Power Outlining Use an outline to organize main ideas The kingdom of Macedonia, located just north of Greece, about the growth of had rough terrain and a cold climate. The Macedonians were Alexander's empire. a hardy people who lived in mountain villages rather than city-states. Most Macedonian nobles thought of themselves Alexander's Empire as Greeks. The Greeks, however, looked down on the I. Philip Builds Macedonian Power Macedonians as uncivilized foreigners who had no great A. philosophers, sculptors, or writers. The Macedonians did have one very B. important resource—their shrewd and fearless kings. II. Alexander Conquers Persia Philip’s Army In 359 B.C., Philip II became king of Macedonia. Though only 23 years old, he quickly proved to be a brilliant general and a ruthless politician. Philip transformed the rugged peasants under his command into a well-trained professional army. -

The Resurrection of Alexander Push Kin John Oliver Killens

New Directions Volume 5 | Issue 2 Article 9 1-1-1978 The Resurrection Of Alexander Push kin John Oliver Killens Follow this and additional works at: http://dh.howard.edu/newdirections Recommended Citation Killens, John Oliver (1978) "The Resurrection Of Alexander Push kin," New Directions: Vol. 5: Iss. 2, Article 9. Available at: http://dh.howard.edu/newdirections/vol5/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Directions by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TH[ ARTS Essay every one of the courts of Europe, then 28 The Resurrection of of the 19th century? Here is how it came to pass. Peter felt that he had to have at least Alexander Pushkin one for his imperial court. Therefore, In the early part of the 18th century, in By [ohn Oliver Killens he sent the word out to all of his that sprawling subcontinent that took Ambassadors in Europe: To the majority of literate Americans, up one-sixth of the earth's surface, the giants of Russian literature are extending from the edge of Europe "Find me a Negro!" Tolstoy, Gogol, Dostoevsky and thousands of miles eastward across Meanwhile, Turkey and Ethiopia had Turgenev. Nevertheless, 97 years ago, grassy steppes (plains), mountain ranges been at war, and in one of the skirmishes at a Pushkin Memorial in Moscow, and vast frozen stretches of forest, lakes a young African prince had been cap- Dostoevsky said: "No Russian writer and unexplored terrain, was a land tured and brought back to Turkey and was so intimately at one with the known as the Holy Russian Empire, fore- placed in a harem. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the -

Teaching English with a Pluricentric Approach: a Compilation of Four Upper Secondary Teachers’ Beliefs

Faculty of Education and Society Department of Culture, Languages and Media Degree Project in English Studies and Education 15 Credits, Advanced Level Teaching English with a Pluricentric Approach: a Compilation of Four Upper Secondary Teachers’ Beliefs Att undervisa i engelska med ett pluricentriskt tillvägagångssätt: en sammanställning av fyra gymnasielärares föreställningar Agnes Rauer and Elena Tizzano Master of Arts/Science in Education, 300 Credits Supervisor: Vi Thanh Son 2019-06-09 Examiner: Anna Korshin Wärnsby Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the upper secondary teachers who agreed to participate in our study, without them it would have been no study at all. We also want to thank Malin Reljanovic Glimäng for making us aware of how the English language is used in the globalized world and also for guiding our first steps in this field of research. And last but not least, we would like to thank our supervisor Vi Thanh Son for guiding and supporting us through this writing process. Contribution to the Synthesis This degree project is a result of a collaborative and equally divided effort. The research, collecting of data and the writing has been fairly distributed among the students/writers. The writing was carried out in a process made of virtual, as well as physical meetings, and facilitated by the use of Google Docs. By using this tool it was possible to follow each other’s creative process and give thorough feedback in order to improve the project. The workload was continuously discussed and adjusted throughout the writing-process and we both gained a deep knowledge of the contents of the text. -

Criminal Code

Criminal Code Warning: this is not an official translation. Under all circumstances the original text in Dutch language of the Criminal Code (Wetboek van Strafrecht) prevails. The State accepts no liability for damage of any kind resulting from the use of this translation. Criminal Code (Text valid on: 01-10-2012) Act of 3 March 1881 We WILLEM III, by the grace of God, King of the Netherlands, Prince of Orange-Nassau, Grand Duke of Luxemburg etc. etc. etc. Greetings to all who shall see or hear these presents! Be it known: Whereas We have considered that it is necessary to enact a new Criminal Code; We therefore, having heard the Council of State, and in consultation with the States General, have approved and decreed as We hereby approve and decree, to establish the following provisions which shall constitute the Criminal Code: Book One. General Provisions Part I. Scope of Application of Criminal Law Section 1 1. No act or omission which did not constitute a criminal offence under the law at the time of its commission shall be punishable by law. 2. Where the statutory provisions in force at the time when the criminal offence was committed are later amended, the provisions most favourable to the suspect or the defendant shall apply. Section 2 The criminal law of the Netherlands shall apply to any person who commits a criminal offence in the Netherlands. Section 3 The criminal law of the Netherlands shall apply to any person who commits a criminal offence on board a Dutch vessel or aircraft outside the territory of the Netherlands. -

Anneke Jans' Maternal Grandfather and Great Grandfather

Anneke Jans’ Maternal Grandfather and Great Grandfather By RICIGS member, Gene Eiklor I have been writing a book about my father’s ancestors. Anneke Jans is my 10th Great Grandmother, the “Matriarch of New Amsterdam.” I am including part of her story as an Appendix to my book. If it proves out, Anneke Jans would be the granddaughter of Willem I “The Silent” who started the process of making the Netherlands into a republic. Since the records and info about Willem I are in the hands of the royals and government (the Royals are buried at Delft under the tomb of Willem I) I took it upon myself to send the Appendix to Leiden University at Leiden. Leiden University was started by Willem I. An interesting fact is that descendants of Anneke have initiated a number of unsuccessful attempts to recapture Anneke’s land on which Trinity Church in New York is located. In Chapter 2 – Dutch Settlement, page 29, Anneke Jans’ mother was listed as Tryntje (Catherine) Jonas. Each were identified as my father’s ninth and tenth Great Grandmothers, respectively. Since completion of that and succeeding chapters I learned from material shared by cousin Betty Jean Leatherwood that Tryntje’s husband had been identified. From this there is a tentative identification of Anneke’s Grandfather and Great Grandfather. The analysis, the compilation and the writings on these finds were done by John Reynolds Totten. They were reported in The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Volume LVI, No. 3, July 1925i and Volume LVII, No. 1, January 1926ii Anneke is often named as the Matriarch of New Amsterdam. -

German and English Noun Phrases

RICE UNIVERSITY German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach Ward Keith Barrows A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF 3 1272 00675 0689 Master of Arts Thesis Directors signature: / Houston, Texas April, 1971 Abstract: German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach, by Ward Keith Barrows The paper presents a contrastive approach to German and English based on the theory of transformational grammar. In the first chapter, contrastive analysis is discussed in the context of foreign language teaching. It is indicated that contrastive analysis in pedagogy is directed toward the identification of sources of interference for students of foreign languages. It is also pointed out that some differences between two languages will prove more troublesome to the student than others. The second chapter presents transformational grammar as a theory of language. Basic assumptions and concepts are discussed, among them the central dichotomy of competence vs performance. Chapter three then present the structure of a grammar written in accordance with these assumptions and concepts. The universal base hypothesis is presented and adopted. An innovation is made in the componential structire of a transformational grammar: a lexical component is created, whereas the lexicon has previously been considered as part of the base. Chapter four presents an illustration of how transformational grammars may be used contrastively. After a base is presented for English and German, lexical components and some transformational rules are contrasted. The final chapter returns to contrastive analysis, but discusses it this time from the point of view of linguistic typology in general.