Press Release YAN LI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zhang Hongtu / Hongtu Zhang: an Interview'

An Interview with Zhang Hongtu 281 the roots - Chinese culture - had already become part of my life just as a tail is a part of a dog's body. I'm like a dog: the tail will be with me for 10 ever, no matter where I go. Sure, after nine years away from China, I forget many things, like I forget that when you buy lunch you have to pay Zhang Hongtu / Hongtu Zhang: ration coupons with the money, and how much political pressure there An Interview' was in my everyday life. But because I still keep reading Chinese books and thinking about Chinese culture, and especially because I have the opportunity to see the differences between Chinese culture and the Western culture which I learned about after I left China, my image of Chinese culture has become more clear. Su Dongpo (the poet, I036- Zhang Hongtu was born in Gansu province, in northwest China, in lIOI) said: Bu shi Lushan zhen mianmu / Zhi yuan shen zai si shan I943, but grew up in Beijing. After studies at the Central Academy of zbong, Which means, one can't see the image of Mt. Lu because one is Arts and Crafts in Beijing, he was later assigned to work as a design inside the mountain. Now that I'm outside of the mountain, I can see supervisor in a jewellery company. In I982, he left China to pursue a what the image of the mountain is, so from this point of view I would say career as a painter in New York. -

Joan Lebold Cohen Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT JOAN LEBOLD COHEN Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise Date:31 Oct 2009 Duration: about 2 hours Location: New York Jane DeBevoise (JD): It would be great if you could speak a little bit about how you got to China, when you got to China – with dates specific to the ‘80s, and how you saw the 80’s develop. From your perspective what were some of the key moments in terms of the arts? Joan Lebold Cohen (JC): First of all, I should say that I had been to China three times before the 1980s. I went twice in 1972, once on a delegation in May for over three weeks, which took us to Beijing, Luoyang, Xi’an, and Shanghai and we flew into Nanchang too because there were clouds over Guangzhou and the planes couldn’t fly in. This was a period when, if you wanted to have a meal and you were flying, the airplane would land so that you could go to a restaurant (Laughter). They were old, Russian airplanes, and you sat in folding chairs. The conditions were rather…primitive. But I remember going down to the Shanghai airport and having the most delicious ‘8-precious’ pudding and sweet buns – they were fantastic. I also went to China in 1978. For each trip, I had requested to meet artists and to go to exhibitions, but was denied the privilege. However, there was one time, when I went to an exhibition in May of 1972 and it was one of the only exhibitions that exhibited Cultural Revolution model paintings; it was very amusing. -

Andreas Schmid Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT ANDREAS SCHMID Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise, Anthony Yung Date: 27 Apr 2008 Duration: about 2 hours Location: Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong Question (Q): Why did you go to China? Where you and what were you doing? Who are some of the artists that you encountered and what do you think about them? What were the artists reading and what are your comments on those materials? Andreas Schmid (AS): I graduated from the Art Academy in Stuttgart in 1981, studying painting. My paintings were, at that time, very different from German painters like Kiefer in that they always have free space, and transparency of layers of space in them. I painted with oil and acrylic, and it was different from my colleagues/contemporaries. I became interested in the idea of space, of Chinese Art, classical Chinese art, like Ni Zan [倪赞] in the fourteenth century. Then I went to Cologne and saw a collection of Japanese Buddhist writings collected by Seiko Kono , abbot of the Daian-ji temple in Nara City , Japan. I would like to know the line from another side, because lines played the most important role graphically in my paintings. So I tried contacting organizations that would support me, and they informed me there was only one woman who went to China as an artist from Germany with the support of the German exchange service. I went to see her, and she had studied in Hangzhou one year ago at that time (1980). She studied birds and flowers painting. She told me, if you want to do this, you should go to China, it is interesting. -

Summer 2020 Degrees Conferred

THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Australia Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Fofanah, Osman Ngunnawal 2913 Bachelor of Science in Education THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY OSAS - Analysis and Reporting November 17, 2020 Page 1 of 42 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Bangladesh Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Helal, Abdullah Al Dhaka 1217 Master of Science Alam, Md Shah Comilla 3510 Master of Science THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY OSAS - Analysis and Reporting November 17, 2020 Page 2 of 42 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Bolivia Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Arrueta Antequera, Lourdes Delta El Alto Master of Science THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY OSAS - Analysis and Reporting November 17, 2020 Page 3 of 42 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Brazil Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor dos Santos Marques, Ana Carolina Sao Jose Do Rio Pre 15015 Doctor of Philosophy Marotta Gudme, Erik Rio De Janeiro 22460 Bachelor of Science in Business Administration Magna Cum Laude Pereira da Cruz Benetti, Lucia Porto Alegre 90670 Doctor -

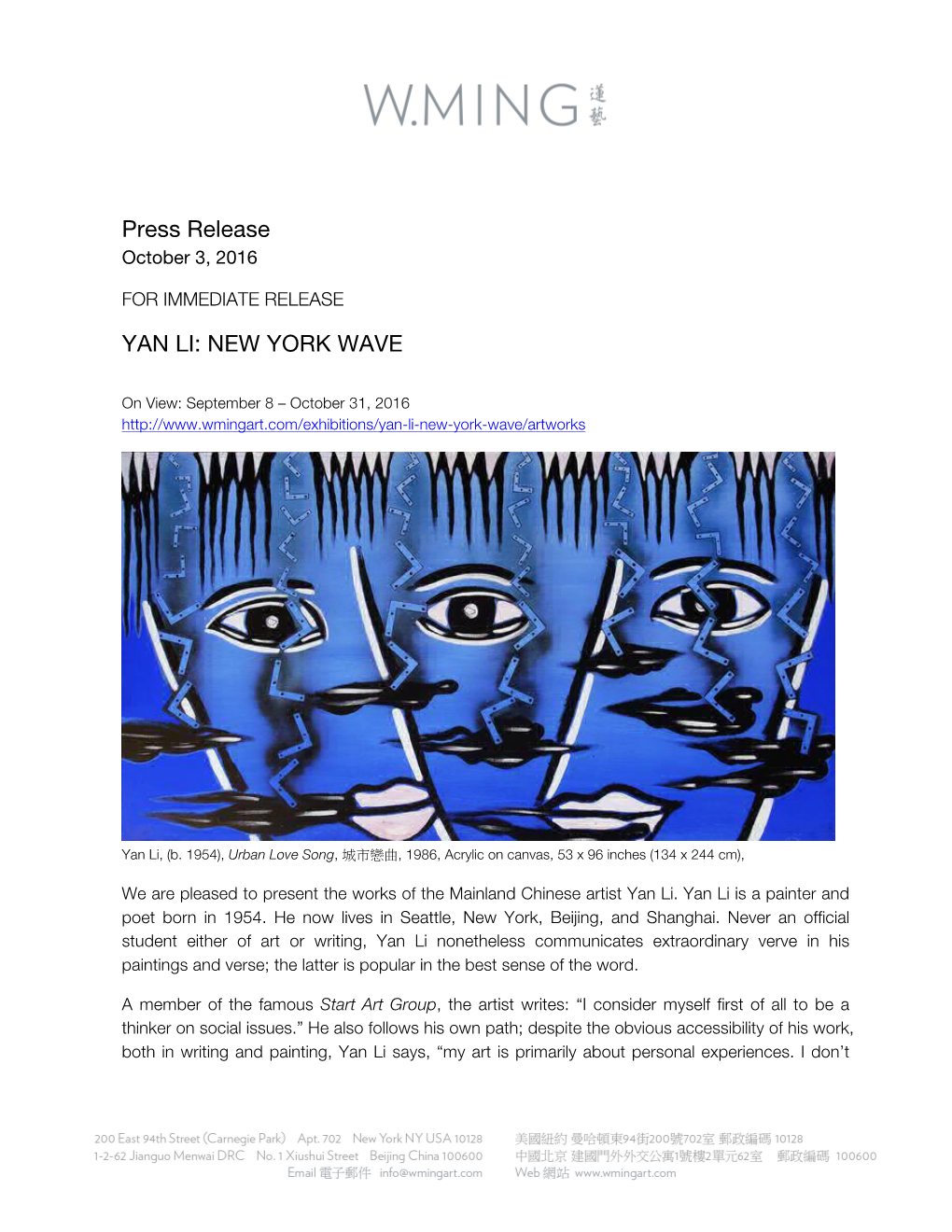

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin

“Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 ABSTRACT “Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 Copyright by Muyun Zhou 2021 Abstract In his world literature lecture series running from 1989 to 1994, the Chinese diasporic writer-painter Mu Xin (1927-2011) provided a puzzling proposition for a group of emerging Chinese artists living in New York: “Art is to sacrifice.” Reading this proposition in tandem with Mu Xin’s other comments on “sacrifice” from the lecture series, this study examines the intricate relationship between aesthetics and ethics in Mu Xin’s project of art. The question of diasporic positionality is inherent in the relationship between aesthetic and ethical discourses, for the two discourses were born in a Western tradition, once foreign to Mu Xin. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Asia Society Hong Kong Center Presents

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Asia Society Hong Kong Center presents Light Before Dawn: Unofficial Chinese Art 1974-1985 On view at Asia Society Gallery (Former Magazine A) May 15 - September 1, 2013 (Hong Kong, May 13, 2013) Asia Society Hong Kong Center today announced that Light Before Dawn: Unofficial Chinese Art 1974 – 1985, will be unveiled to audiences at Asia Society Hong Kong Center from May 15-September 1. The exhibition offers a revealing look into the spectrum of work created by three of China’s most influential contemporary art groups: Wuming (No Name), Xingxing (Stars), and Caocao (Grass Society). Light Before Dawn presents the works of twenty-two artists from the three art groups of Wuming, Xingxing and Caocao, emerged from the Cultural Revolution, who sought artistic truth in the authenticity of human desire, pain and dreams, explored the personal meaning of creativity, and asserted the value of the individuals. Crossing the boundaries of subject matter and style, they questioned, re-evaluated and redefined the forms, the nature of beauty and the art of China. Distinctive in their art approaches, the Wuming group retained an interest in representations of nature, the Xingxing group explored historically Western modes of modernism, absorbing anew, progressive styles developed in Europe and America during the early twentieth century, including surrealism, cubism, and abstract expressionism while the Caocao group, trained in the native medium of ink and color on paper, attempted to shed both the legacy of socialist realism and the burdens of tradition by turning to new forms of abstract ink painting. Although each movement took a distinctly different artistic approach, they were united in their commitment to pushing Chinese art beyond the borders of Socialist Realism. -

Nameless Art in the Mao Era

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2017 Nameless Art in the Mao Era Tianchu Gao College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, and the Modern Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Gao, Tianchu, "Nameless Art in the Mao Era" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1091. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1091 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nameless Art in the Mao Era A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Department of Art and Art History from The College of William and Mary by Tianchu (Jane) Gao 高天楚 Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, Non-Honors) ________________________________________ Xin Wu, Director ________________________________________ Sibel Zandi-Sayek ________________________________________ Charles Palermo ________________________________________ Michael Gibbs Hill Williamsburg, VA May 2, 2017 ABSTRACT This research project focuses on the first generation of No Name (wuming 無名), an underground art group in the Cultural Revolution which secretly practiced art countering the official Socialist Realism because of its non-realist visual language and art-for-art’s-sake philosophy. These artists took advantage of their worker status to learn and practice art legitimately in the Mass Art System of the time. They developed their particular style and vision of art from their amateur art training, forbidden visual and textual sources in the underground cultural sphere, and official theoretical debates on art. -

Chinese Contemporary Art-7 Things You Should Know

Chinese Contemporary Art things you should know By Melissa Chiu Contents Introduction / 4 1 . Contemporary art in China began decades ago. / 14 2 . Chinese contemporary art is more diverse than you might think. / 34 3 . Museums and galleries have promoted Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. / 44 4 . Government censorship has been an influence on Chinese artists, and sometimes still is. / 52 5 . The Chinese artists’ diaspora is returning to China. / 64 6 . Contemporary art museums in China are on the rise. / 74 7 . The world is collecting Chinese contemporary art. / 82 Conclusion / 90 Artist Biographies / 98 Further Reading / 110 Introduction 4 Sometimes it seems that scarcely a week goes by without a newspaper or magazine article on the Chinese contemporary art scene. Record-breaking auction prices make good headlines, but they also confer a value on the artworks that few of their makers would have dreamed possible when those works were originally created— sometimes only a few years ago, in other cases a few decades. It is easy to understand the artists’ surprise at their flourishing market and media success: the secondary auction market for Chinese contemporary art emerged only recently, in 2005, when for the first time Christie’s held a designated Asian Contemporary Art sale in its annual Asian art auctions in Hong Kong. The auctions were a success, including the modern and contemporary sales, which brought in $18 million of the $90 million total; auction benchmarks were set for contemporary artists Zhang Huan, Yan Pei-Ming, Yue Minjun, and many others. The following year, Sotheby’s held its first dedicated Asian Contemporary sale in New York. -

Innovation Und Wandel Durch Chinas Heimgekehrte Akademiker?

Reverse Brain Drain: Innovation und Wandel durch Chinas heimgekehrte Akademiker? Eine Studie zum Einfluss geistes- und sozialwissenschaftlicher Rückkehrer am Beispiel chinesischer Eliteuniversitäten Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades der Doktorin der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Hamburg im Promotionsfach Sinologie vorgelegt von Birte Klemm Hamburg, 2017 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael Friedrich Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Yvonne Schulz Zinda Datum der Disputation: 14. August 2018 游学, 明时势,长志气,扩见闻,增才智, 非游历外国不为功也. 张之洞 1898 年《劝学篇·序》 Danksagung Ohne die Unterstützung einer Vielzahl von Menschen wäre diese Dissertation nicht zustande ge- kommen. Mein besonderer Dank gilt dem Betreuer dieser Arbeit, Prof. Dr. Michael Friedrich, für seine große Hilfe bei den empirischen Untersuchungen und die wertvollen Ratschläge bei der Erstellung der Arbeit. Für die Zweitbegutachtung möchte ich mich ganz herzlich bei Frau Prof. Dr. Yvonne Schulz Zinda bedanken. In der Konzeptionsphase des Projekts haben mich meine ehemaligen Kolleginnen und Kollegen am GIGA Institut für Asien-Studien, vor allem Prof. Dr. Thomas Kern, mit fachkundigen Ge- sprächen unterstützt. Ein großes Dankeschön geht überdies an Prof. Dr. Wang Weijiang und seine ganze Familie, an Prof. Dr. Chen Hongjie, Prof. Dr. Zhan Ru und Prof. Dr. Shen Wenzhong, die mir während meiner empirischen Datenerhebungen in Peking und Shanghai mit überwältigender Gastfreundschaft und Expertise tatkräftig zur Seite standen und viele Türen öffneten. An dieser Stelle möchte ich auch die zahlreichen Teilnehmerinnen und Teilnehmern der empiri- schen Umfragen dieser Studie würdigen. Hervorheben möchte ich die Studierenden der Beida und Fudan, die mir sehr bei der Verteilung der Fragebögen halfen und mir vielfältige Einblicke in das chinesische Hochschulwesen sowie studentische und universitäre Leben ermöglichten. -

Chinese Art Outside China Published by Edizioni Charta

Breakout: Chinese Art Outside China Published by Edizioni Charta. Milano, Italy, 2007 Jonathan Goodman ell conceived and well written, Melissa Chiu’s Breakout: Chinese Art Outside China Wconsiders the Chinese artistic diaspora— painters and sculptors, performance artists and conceptual practitioners who left the Mainland in favour of greater aesthetic freedom in America, Europe, and Australia. After the events on June 4, 1989, at Tian’anmen Square, the democracy movement in China was crushed, and many artists sought to escape what had become a prison house for the intelligentsia. At the same time, however, as Chiu points out in a perceptive introduction, there was a general exodus that had to do with cultural restlessness as much as political oppression. She finds that not everybody wanted to leave; she quotes Ah Xian, Cover of Breakout: Chinese Art Outside China. a ceramic artist who settled in Australia: “Once we had Image: Ah Xian, Human Human—Landscape 1, 00-00. Courtesy Edizioni Charta, Milano. the chance to go overseas, we tried as hard as we could to stay” . And most recently, many Chinese artists have returned to China, including such major figures as Zhang Huan, who never gave up his Chinese passport while working in America, and Xu Bing, who has accepted the post of vice president at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, where he received his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees more than two decades ago. Chiu rightly suggests that the ebb and flow of immigration by Chinese artists is complicated, and much of her book, which is devoted to case studies of individual artists, claims a greater complexity for these figures than what the general perception might assert. -

Mao in Tibetan Disguise History, Ethnography, and Excess

2012 | HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2 (1): 213–245 Mao in Tibetan disguise History, ethnography, and excess Carole MCGRANAHAN, University of Colorado What Does ethnographic theory look like in Dialogue with historical anthropology? Or, what Does that theory contribute to a Discussion of Tibetan images of Mao ZeDong? In this article, I present a renegaDe history told by a Tibetan in exile that Disguises Mao in Tibetan Dress as part of his journeys on the Long March in the 1930s. BeyonD assessing its histori- cal veracity, I consider the social truths, cultural logics, and political claims embeDDeD in this history as examples of the productive excesses inherent in anD generateD by conceptual Disjunctures. KeyworDs: History, Tibet, Mao, Disjuncture, excess In the back room of an antique store in Kathmandu, I heard an unusual story on a summer day in 1994. Narrated by Sherap, the Tibetan man in his 50s who owned the store, it was about when Mao Zedong came to Tibet as part of the communist Long March through China in the 1930s in retreat from advancing Kuomintang (KMT) troops.1 “Mao and Zhu [De],” he said, “were together on the Long March. They came from Yunnan through Lithang and Nyarong, anD then to a place calleD Dapo on the banks of a river, anD from there on to my hometown, Rombatsa. Rombatsa is the site of Dhargye Gonpa [monastery], which is known for always fighting with the Chinese. Many of the Chinese DieD of starvation, anD they haD only grass shoes to wear. Earlier, the Chinese haD DestroyeD lots of Tibetan monasteries.