Book Review: the Fan Who Knew Too Much - WSJ.Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aretha Franklin Discography Torrent Download Aretha Franklin Discography Torrent Download

aretha franklin discography torrent download Aretha franklin discography torrent download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d32277da864db8 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Aretha franklin discography torrent download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d322789d5f4e08 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. -

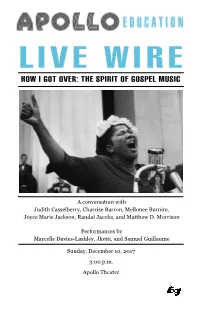

View the Program Book for How I Got Over

A conversation with Judith Casselberry, Charrise Barron, Mellonee Burnim, Joyce Marie Jackson, Randal Jacobs, and Matthew D. Morrison Performances by Marcelle Davies-Lashley, Jhetti, and Samuel Guillaume Sunday, December 10, 2017 3:00 p.m. Apollo Theater Front Cover: Mahalia Jackson; March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 1957 LIVE WIRE: HOW I GOT OVER - THE SPIRIT OF GOSPEL MUSIC In 1963, when Mahalia Jackson sang “How I Got Over” before 250,000 protesters at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, she epitomized the sound and sentiment of Black Americans one hundred years after Emancipation. To sing of looking back to see “how I got over,” while protesting racial violence and social, civic, economic, and political oppression, both celebrated victories won and allowed all to envision current struggles in the past tense. Gospel is the good news. Look how far God has brought us. Look at where God will take us. On its face, the gospel song composed by Clara Ward in 1951, spoke to personal trials and tribulations overcome by the power of Jesus Christ. Black gospel music, however, has always occupied a space between the push to individualistic Christian salvation and community liberation in the context of an unjust society— a declaration of faith by the communal “I”. From its incubation at the turn of the 20th century to its emergence as a genre in the 1930s, gospel was the sound of Black people on the move. People with purpose, vision, and a spirit of experimentation— clear on what they left behind, unsure of what lay ahead. -

I Sing Because I'm Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy For

―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer D. M. A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Yvonne Sellers Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Loretta Robinson, Advisor Karen Peeler C. Patrick Woliver Copyright by Crystal Yvonne Sellers 2009 Abstract ―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer With roots in the early songs and Spirituals of the African American slave, and influenced by American Jazz and Blues, Gospel music holds a significant place in the music history of the United States. Whether as a choral or solo composition, Gospel music is accompanied song, and its rhythms, textures, and vocal styles have become infused into most of today‘s popular music, as well as in much of the music of the evangelical Christian church. For well over a century voice teachers and voice scientists have studied thoroughly the Classical singing voice. The past fifty years have seen an explosion of research aimed at understanding Classical singing vocal function, ways of building efficient and flexible Classical singing voices, and maintaining vocal health care; more recently these studies have been extended to Pop and Musical Theater voices. Surprisingly, to date almost no studies have been done on the voice of the Gospel singer. Despite its growth in popularity, a thorough exploration of the vocal requirements of singing Gospel, developed through years of unique tradition and by hundreds of noted Gospel artists, is virtually non-existent. -

Famous Song-"Precious Lord" Last Updated Saturday, 11 April 2009 15:40

Famous Song-"Precious Lord" Last Updated Saturday, 11 April 2009 15:40 Thomas A. Dorsey In our last issue (3-28-09) this wonderful Story stated that the song’s author was Tommy Dorsey, a band leader in the 30’s and 40’s. Thanks to Holly Lake Ranch resident, Don Teems, we want to give you the rest of the story. It was Thomas A. Dorsey, a black musician, who was the real composer of Precious Lord and hundreds of other gospel hymns. W.C. THE BIRTH OF THE SONG ‘PRECIOUS LORD' ‘Precious Lord, take my hand, Lead me on, let me stand, I am tired, I am weak, I am worn, Through the storm, through the night, Lead me on to the light, Take my hand, Precious Lord, Lead me home.' When my way grows drear, Precious Lord, linger near, When my life is almost gone, Hear my cry, hear my call, Hold my hand lest I fall: Take my hand, Precious Lord, Lead me home. When the darkness appears And the night draws near, And the day is past and gone, At the river I stand, Guide my feet, hold my hand: 1 / 3 Famous Song-"Precious Lord" Last Updated Saturday, 11 April 2009 15:40 Take my hand, Precious Lord, Lead me home.' The Lord gave me these words and melody. He also healed my spirit. I learned that when we are in our deepest grief, when we feel farthest from God, this is when He is closest, and when we are most open to His restoring power. -

Paper for B(&N

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 9 • No. 9 • September 2019 doi:10.30845/ijhss.v9n9p4 Biographies of Two African American Women in Religious Music: Clara Ward and Rosetta Tharpe Nana A. Amoah-Ramey Ph.D. Indiana University Department of African American and African Diaspora Studies College of Arts and Sciences Ballantine Hall 678 Bloomington IN, 47405, USA Abstract This paper‟s focus is to compare the lives, times and musical professions of two prominent African American women— Clara Ward and Rosetta Thorpe — in religious music. The study addresses the musical careers of both women and shows challenges that they worked hard to overcome, and how their relationship with other musicians and the public helped to steer their careers by making them important figures in African American gospel and religious music. In pursuing this objective, I relied on manuscripts, narratives, newspaper clippings, and published source materials. Results of the study points to commonalities or similarities between them. In particular, their lives go a long way to confirm the important contributions they made to religious music of their day and even today. Keywords: African American Gospel and Religious Music, Women, Gender, Liberation, Empowerment Overview This paper is structured as follows: It begins with a brief discussion of the historical background of gospel and sacred music. This is followed by an examination of the musical careers of Clara Ward and Rosetta Thorpe with particular attention to the challenges they faced and the strategies they employed to overcome such challenges; and by so doing becoming major figures performing this genre (gospel and sacred music) of music. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

NEW TEMPLE MISSIONARY BAPTIST CHURCH 8730-8736 South Broadway; 247-259 West 87Th Place CHC-2019-4225-HCM ENV-2019-4226-CE

NEW TEMPLE MISSIONARY BAPTIST CHURCH 8730-8736 South Broadway; 247-259 West 87th Place CHC-2019-4225-HCM ENV-2019-4226-CE Agenda packet includes: 1. Final Determination Staff Recommendation Report 2. City Council Motion 19-0310 3. Commission/ Staff Site Inspection Photos—June 27, 2019 4. Staff Site Inspection Photos—March 27, 2019 5. Categorical Exemption 6. Historic-Cultural Monument Application 7. Letter of Support from Owner Please click on each document to be directly taken to the corresponding page of the PDF. Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2019-4225-HCM ENV-2019-4226-CE HEARING DATE: August 1, 2019 Location: 8730-8736 South Broadway; TIME: 10:00 AM 247-259 West 87th Place PLACE: City Hall, Room 1010 Council District: 8 – Harris-Dawson 200 N. Spring Street Community Plan Area: Southeast Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA 90012 Area Planning Commission: South Los Angeles Neighborhood Council: Empowerment Congress EXPIRATION DATE: August 5, 2019 Southeast Area Legal Description: Tract 337, Lots FR 2, 4, and 6 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the NEW TEMPLE MISSIONARY BAPTIST CHURCH REQUEST: Declare the property an Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER: New Temple Missionary Baptist Church 8734 South Broadway Los Angeles, CA 90003 APPLICANT: City of Los Angeles 221 North Figueroa Street, Suite 1350 Los Angeles, CA 90012 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Declare the subject property an Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.7. 2. Adopt the staff report and findings. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

Black Women in the United States Lady Day to Lizzo: a Century Of

AF21:014:305: Black Women in the United States Lady Day to Lizzo: A Century of Black Women Performers Professor Salamishah Tillet // [email protected] Tuesdays 2:30 - 5:30 pm Office Hours: Wednesdays 4 to 5 and by appt. Teaching Assistant: Esperanza Santos // [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesdays 4 to 5 and by appt. Course Description African American women performers from the blueswoman Bessie Smith to gospel guitarist Rosetta Tharpe, from jazz darling Billie Holiday to megastar star Beyoncé, and from hip hop virtuoso Lauryn Hill to millennial polymath Lizzo, have constantly redefined and expanded American popular music. This course will explore the long century of African American history through Black women performers, who across genres and time, have consciously and sometimes contradictorily navigated the racial and sexual limits of American popular culture in order to assert artistic agency and political freedom. Class Expectations Attendance and active class participation are required. Late assignments will not be accepted except in cases of proven emergency. If you know that you will be absent on a on a particular day, plan ahead and give your feedback to the class accordingly. We are ALL required to follow the University’s Policy on Academic Integrity, which falls under the Code of Student Conduct. The policy and the consequences of violating it are 1 outlined here: http://www.ncas.rutgers.edu/office-dean-student-affairs/academic-integrity-policy. Disabilities Rutgers University welcomes students with disabilities into all of the University's educational programs. In order to receive consideration for reasonable accommodations, a student with a disability must contact the appropriate disability services office at the campus where you are officially enrolled, participate in an intake interview, and provide documentation: https://ods.rutgers.edu/students/documentation-guidelines. -

Coronet 1956-1962

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS THE CORONET LABEL 1956–1962 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER OCTOBER 2019 CORONET, 1956–1962 THE CORONET LABEL MADE ITS DEBUT IN JANUARY 1956. PRIOR TO ITS ACQUISITION BY A.R.C., TITLES FROM THE U.S. COLUMBIA CATALOGUE WERE RELEASED IN AUSTRALIA THROUGH PHILIPS RECORDS. CORONET KLC CLASSICAL 12” AND KGC 7” EP’S ARE NOT LISTED HERE CORONET KP SERIES 78’S KP-001 BIBLE TELLS ME SO / SATISFIED MIND MAHALIA JACKSON 2.56 KP-002 OOH BANG JIGGILY JANG / JIMMY UNKNOWN DORIS DAY 1.56 KP-003 MAYBELLINE / THIS BROKEN HEART OF MINE MARTY ROBBINS 1.56 KP-004 I WISH I WAS A CAR / REMEMB'RING PETER LIND HAYES 4.56 KP-005 BONNIE BLUE GAL / BEL SANTE MITCH MILLER AND HIS ORCHESTRA 3.56 KP-006 SIXTEEN TONS / WALKING THE NIGHT AWAY FRANKIE LAINE 1.56 KP-007 PIZZICATO WALTZ / SKIDDLES GEORGE LIBERACE & HIS ORCHESTRA 2.56 KP-008 HEY THERE! / WAKE ME ROSEMARY CLOONEY KP-009 HEY THERE! / HERNANDO'S HIDEAWAY JOHNNIE RAY KP-010 BAND OF GOLD / RUMBLE BOOGIE DON CHERRY 3.56 KP-011 MEMORIES OF YOU / IT'S BAD FOR ME ROSEMARY CLOONEY KP-012 LEARNING TO LOVE / SONG OF SEVENTEEN PEGGY KING KP-013 TELL ME THAT YOU LOVE ME / HOW CAN I REPLACE YOU TONY BENNETT 2.56 KP-014 TOUCH OF LOVE / WITH ALL MY HEART VAL VALENTE 1.56 KP-015 WHO'S SORRY NOW? / A HEART COMES IN HANDY JOHNNIE RAY 2.56 KP-016 TAKE MY HAND / HAPPINESS IS A THING CALLED JOE JERRI ADAMS 6.56 KP-017 JOHNNIE'S COMIN' HOME / LOVE, LOVE, LOVE JOHNNIE RAY 1.56 KP-018 LET IT RING / LOVE'S LITTLE ISLAND DORIS DAY KP-019 LAND OF THE PHARAOHS / THE WORLD IS MINE PERCY FAITH AND HIS ORCHESTRA -

Aretha Franklin: Aretha Karriereumspannendes Boxset Deckt Nahezu 60 Jahre Ab

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] ARETHA FRANKLIN: ARETHA KARRIEREUMSPANNENDES BOXSET DECKT NAHEZU 60 JAHRE AB 4-CD- und digitale Sammlung widmet sich mit 81 Tracks der Queen Of Soul, darunter 19 zuvor unveröffentlichte alternative Versionen, Demos, Raritäten, und besondere Live-Performances 2-LP und 1-CD Versionen mit Highlights vom Boxset; alle Formate ab dem 20. November über Rhino erhältlich ARETHA FRANKLIN ARETHA Tracklisting Disc One 1. “Never Grow Old” 2. “You Grow Closer” 3. “Today I Sing The Blues” 4. “Won’t Be Long” 5. “Are You Sure” 6. “Operation Heartbreak” 7. “Skylark” 8. “Runnin’ Out Of Fools” 9. “One Step Ahead” 10. “(No, No) I’m Losing You” 11. “Cry Like A Baby” 12. “A Little Bit Of Soul” 13. “My Kind Of Town (Detroit Is)” – Demo * 14. “Try A Little Tenderness” – Demo * 15. “I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Love You)” 16. “Do Right Woman – Do Right Man” 17. “Respect” 18. “A Change Is Gonna Come” 19. “Chain Of Fools” – Alternate Version 20. “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” – UK Single Version 21. “(Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've Been Gone” 22. “Ain’t No Way” 23. “My Song” 24. “You Send Me” 25. “The House That Jack Built” 26. “Tracks Of My Tears” Disc Two 1. “Baby I Love You” – Live 2. “Son Of A Preacher Man” 3. “Call Me” – Alternate Version * 4. “Let It Be” 5. “Young, Gifted And Black” – Alternate Longer Take * 6. “Bridge Over Troubled Water” – Long Version 7. -

ARETHA FRANKLIN the Queen of Soul 4-CD Boxset 87 Klassiker Von Der Königin Des Soul

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] ARETHA FRANKLIN The Queen Of Soul 4-CD Boxset 87 Klassiker von der Königin des Soul Disc One 1. “I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Love You)” 2. “Do Right Woman - Do Right Man” 3. “Respect” 4. “Drown In My Own Tears” 5. “Soul Serenade” 6. “Don’t Let Me Lose This Dream” 7. “Baby, Baby, Baby” 8. “Dr. Feelgood (Love Is A Serious Business)” 9. “Good Times” 10. “Save Me” 11. “Baby, I Love You” 12. “Satisfaction” 13. “You Are My Sunshine” 14. “Never Let Me Go” 15. “Prove It” 16. “I Wonder” 17. “Ain’t Nobody (Gonna Turn Me Around)” 18. “It Was You” (Aretha Arrives Outtake) 19. “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” 20. “Chain Of Fools” 21. “People Get Ready” 22. “Come Back Baby” 23. “Good To Me As I Am To You” 24. “Since You’ve Been Gone (Sweet Sweet Baby)” 25. “Ain’t No Way” Disc Two 1. “Think” 2. “You Send Me” 3. “I Say A Little Prayer” 4. “The House That Jack Built” 5. “You’re A Sweet Sweet Man” 6. “I Take What I Want” 7. “A Change” 8. “See Saw” 9. “My Song” 10. “I Can’t See Myself Leaving You” 11. “Night Life” (Live) 12. “Ramblin’” 13. “Today I Sing The Blues” 14. “River’s Invitation” 15. “Pitiful” 16. “Talk To Me, Talk To Me” (Soul ‘69 Outtake) 17. “Tracks Of My Tears” 18. “The Weight” 19.