Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Review: the Fan Who Knew Too Much - WSJ.Com

Book Review: The Fan Who Knew Too Much - WSJ.com http://online.wsj.com/article/SB1000142405270230390150457... Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit www.djreprints.com See a sample reprint in PDF format. Order a reprint of this article now BOOKSHELF Updated June 29, 2012, 5:30 p.m. ET The Queen of Soul's Long Reign By EDDIE DEAN One of the more indelible moments from the Obama inauguration was the spectacle of Aretha Franklin singing her gospel rendition of "My Country, 'Tis of Thee," as poignant to watch as it was painful to hear. Bundled in an overcoat, gloves and a Sunday-go-to-meeting hat with a jumbo ribbon bow, she struggled in the raw winter cold to kindle her time-ravaged voice, once one of the wonders of the modern world. The performance was less about hitting the high notes than striking a chord with the flock: Here was America's Church Lady come to bless her children. It's a role that the 70-year-old Ms. Franklin plays quite well at ceremonies of state and funerals and whenever the occasion demands. But she also enjoys a Saturday night out as the reigning Queen of Soul, as when she regaled a stadium crowd at WrestleMania 23 in 2007 in her hometown of Detroit. Such cameos run the risk of making her a kind of caricature—someone who has overstayed her welcome on the pop-culture stage and become, like Orson Welles in his later years, the honorary emblem of antiquated if revered Americana. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Rocking My Life Away Writing About Music and Other Matters by Anthony Decurtis Rock Critic Lectures on Music

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Rocking My Life Away Writing about Music and Other Matters by Anthony DeCurtis Rock critic lectures on music. 'Rolling Stone' editor Anthony DeCurtis visited Kelly Writers House, but got mixed reviews. By Rebecca Blatt The Daily Pennsylvanian February 22, 2002. Another acclaimed writer visited the Kelly Writers House this week. But this one was not there to discuss poetry or prose -- he was there for rock and roll. On Tuesday afternoon, music critic Anthony DeCurtis spoke to about 25 people in the front room of the Writers House. The crowd included Penn students, professors and local music lovers. DeCurtis is an editor of Rolling Stone magazine, host of an internet music show and the author of Rocking My Life Away: Writing About Music and Other Matters. He won a Grammy Award for his essay accompanying Eric Clapton's Crossroads box set and contributes to many other publications as well. DeCurtis appeared very prepared for the lecture. He took the podium armed with a pad of notes and a pitcher of water. However, some felt that DeCurtis's speech lacked focus. College sophomore Daniel Kaplan was so disappointed with DeCurtis that he left the event early. "He was a writer so pleased with himself and his accomplishments that he seemed to forget that speeches are supposed to be coherent," Kaplan said. Philadelphia resident Hop Wechsler, however, was a little bit more forgiving. "I guess I was expecting more about how he got where he is," Wechsler said. "But what I got was fun for what it was." English Department Chairman David Wallace introduced DeCurtis. -

Kathy Sledge Press

Web Sites Website: www.kathysledge.com Website: http: www.brightersideofday.com Social Media Outlets Facebook: www.facebook.com/pages/Kathy-Sledge/134363149719 Twitter: www.twitter.com/KathySledge Contact Info Theo London, Management Team Email: [email protected] Kathy Sledge is a Renaissance woman — a singer, songwriter, author, producer, manager, and Grammy-nominated music icon whose boundless creativity and passion has garnered praise from critics and a legion of fans from all over the world. Her artistic triumphs encompass chart-topping hits, platinum albums, and successful forays into several genres of popular music. Through her multi-faceted solo career and her legacy as an original vocalist in the group Sister Sledge, which included her lead vocals on worldwide anthems like "We Are Family" and "He's the Greatest Dancer," she's inspired millions of listeners across all generations. Kathy is currently traversing new terrain with her critically acclaimed show The Brighter Side of Day: A Tribute to Billie Holiday plus studio projects that span elements of R&B, rock, and EDM. Indeed, Kathy's reached a fascinating juncture in her journey. That journey began in Philadelphia. The youngest of five daughters born to Edwin and Florez Sledge, Kathy possessed a prodigious musical talent. Her grandmother was an opera singer who taught her harmonies while her father was one-half of Fred & Sledge, the tapping duo who broke racial barriers on Broadway. "I learned the art of music from my father and my grandmother. The business part of music was instilled through my mother," she says. Schooled on an eclectic array of artists like Nancy Wilson and Mongo Santamaría, Kathy and her sisters honed their act around Philadelphia and signed a recording contract with Atco Records. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Download Showbook

SWEET SOUL MUSIC REVUE A Change Is Gonna Come It is August 1955 in Mississippi and a 14-year-old African American, Emmet Louis Till, is being dragged out of his bed by white men. They brutally torture and then drown the boy, because Emmet had whistled at the white village beauty queen and called Bye, bye babe after her. The court acquits the murderers. On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks, an elderly African American lady, refuses to give up her seat on a bus to a white man. She is arrested and taken to court for violating segregation laws. These events in 1955 mark the beginning of the African American Civil Rights Movement, which will grow into a proud political force under the leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King. By 1968 it will have put an end to arbitrary injustice caused by racial segregation in the U.S. There have been times that I thought I couldn‘t last for long / But now I think I‘m able to carry on / It‘s been a long time coming, but I know a change is gonna come – This soul anthem, composed by Sam Cooke in 1963, speaks of the hope for change during these times. Sam himself had been arrested for offences against the laws relating to civil disorders and rioting, because he and his band had tried to check in to a “whites only” motel. Closely linked to the Civil Rights Movement, soul music delivers the soundtrack for this period of political change and upheaval in the United States. -

Aretha Franklin Discography Torrent Download Aretha Franklin Discography Torrent Download

aretha franklin discography torrent download Aretha franklin discography torrent download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d32277da864db8 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Aretha franklin discography torrent download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d322789d5f4e08 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. -

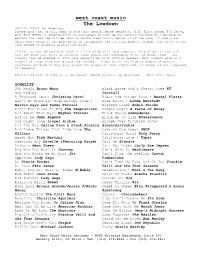

The Lowdown Songlist

west coast music The Lowdown SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need to have your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, F/D Dance, etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm the band will be able to perform the song and will be able to locate sheet music, mp3 or CD of the song. If some cases where sheet music is not printed or an arrangement for the full band is needed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. If you desire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we would ask for a minimum 80 requests. Please feel free to call us at the office should you have any questions. – West Coast Music SONGLIST: 24K Magic Bruno Mars Black Horse And A Cherry Tree KT 90s Medley Tunstall A Thousand Years Christina Perri Bless the Broken Road – Rascal Flatts Ain’t No Mountain High Enough (Duet) Blue Bayou – Linda Ronstadt Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Ain’t Too Proud To Beg The Temptations Boogie Oogie A Taste Of Honey All About That Bass Meghan Trainor Brick House Commodores All Of Me John Legend Bring Me To Life Evanescence All Night Long Lionel Richie Bridge Over Troubled -

URMC V118n83 20091210.Pdf (9.241Mb)

THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN Fort Collins, Colorado COLLEGIAN Volume 118 | No. 8 T D THE STUDENT VOICE OF COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1891 B ASCS ICE, ICE, BABY BOG Leg. a airs director wants student voice on governing board B KIRSTEN SIVEIRA The Rocky ountain Collegian After CSU’s governing board decided to ban concealed weapons on campus, spark- TODAYS IG ing intense controversy student leaders said Wednesday that there must be a student vot- 25 degrees ing member on the board because its mem- bers refuse to listen to students. So far this season, CSU To secure that voting member, Associ- has received a total of 44.2 ated Students of CSU Director of Legislative inches of snow with fi ve full YEAR SEASONA Affairs Matt Worthington drafted a resolu- months of the snow season TOTA IN INCES tion that would allow state leaders to appoint still ahead, according to re- a student to vote on the CSU System Board search from the Department 1 9 9 9 - 2 0 0 0 : 3 . of Governors. The ASCSU Senate moved his of Atmospheric Science. 2 0 0 0 - 2 0 0 1 : 5 resolution to committee Wednesday night. Even if the city receives 2 0 0 1 - 2 0 0 2 : 4 4 .1 ASCSU President Dan Gearhart and CSU- no more snow this winter, 2 0 0 2 - 2 0 0 3 : 1. Pueblo student government President Steve Fort Collins has already re- 2 0 0 3 - 2 0 0 4 : 9 .1 Titus both currently sit on the BOG as non- ceived more snow than in six 2 0 0 4 - 2 0 0 5 : 5 . -

A Change Is Gonna Come

A CHANGE IS GONNA COME: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BENEFITS OF MUSICAL ACTIVISM IN THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT By ERIN NICOLE NEAL A Capstone submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Liberal Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Stuart Z. Charmé And approved by ____________________________________ Dr. Stuart Z. Charmé Camden, New Jersey January 2021 CAPSTONE ABSTRACT A Change Is Gonna Come: A Critical Analysis Of The Benefits Of Musical Activism In The Civil Rights Movement by ERIN NICOLE NEAL Capstone Director: Dr. Stuart Z. Charmé The goal of this Capstone project is to understand what made protest music useful for political activists of the Civil Rights Movement. I will answer this question by analyzing music’s effect on activists through an examination of the songs associated with the movement, regarding lyrical content as well as its musical components. By examining the lyrical content, I will be evaluating how the lyrics of protest songs were useful for the activists, as well as address criticisms of the concrete impact of song lyrics of popular songs. Furthermore, examining musical components such as genre will assist in determining if familiarity in regards to the genre were significant. Ultimately, I found that music was psychologically valuable to political activists because music became an outlet for emotions they held within, instilled within listeners new emotions, became a beacon for psychological restoration and encouragement, and motivated listeners to carry out their activism. Furthermore, from a political perspective, the lyrics brought attention to the current socio-political problems and challenged social standards, furthered activists’ political agendas, persuaded the audience to take action, and emphasized blame on political figures by demonstrating that socio-political problems citizens grappled with were due to governmental actions as well as their inactions. -

Whose Blues?" with Author Adam Gussow November 14, 5Pm ET on TBS Facebook Page

November 2020 www.torontobluessociety.com Published by the TORONTO BLUES SOCIETY since 1985 [email protected] Vol 36, No 11 Sugar Brown (aka Ken Kawashima) will discuss "Whose Blues?" with author Adam Gussow November 14, 5pm ET on TBS Facebook Page CANADIAN PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT #40011871 MBA Nominees Announced Loose Blues News Whose Blues? Blues Reviews Remembering John Valenteyn Blues Events TORONTO BLUES SOCIETY 910 Queen St. W. Ste. B04 Toronto, Canada M6J 1G6 Tel. (416) 538-3885 Toll-free 1-866-871-9457 Email: [email protected] Website: www.torontobluessociety.com MapleBlues is published monthly by the Toronto Blues Society ISSN 0827-0597 2020 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Derek Andrews (President), Janet Alilovic, Jon Arnold, Ron Clarkin (Treasurer), Lucie Dufault (Vice-President), Carol Flett (Secretary), Sarah French, Lori Murray, Ed Parsons, Jordan Safer (Executive), Paul Sanderson, Mike Smith Musicians Advisory Council: Brian Blain, Alana Bridgewater, Jay Douglas, Ken Kawashima, Gary Kendall, Dan McKinnon, Lily Sazz, Mark Stafford, Dione Taylor, Julian Taylor, Jenie Thai, Suzie Vinnick,Ken Whiteley Volunteer & Membership Committee: Lucie Dufault, Rose Ker, Mike Smith, Ed Parsons, Carol Flett Grants Officer: Barbara Isherwood Office Manager: Hüma Üster Marketing & Social Media Manager: Meg McNabb Publisher/Editor-in-Chief: Derek Andrews Many thanks to Betty Jackson and Geoff Virag for their help at the Managing Editor: Brian Blain Toronto Blues Society Talent Search. [email protected] Contributing Editors: Janet Alilovic, Hüma Üster, Carol Flett Listings Coordinator: Janet Alilovic Attention TBS Members! Mailing and Distribution: Ed Parsons Due to COVID-19 pandemic, TBS is unable to deliver a physical Advertising: Dougal Bichan [email protected] copy of the MapleBlues November issue. -

Selective Tradition and Structure of Feeling in the 2008 Presidential Election: a Genealogy of “Yes We Can Can”

Selective Tradition and Structure of Feeling in the 2008 Presidential Election: A Genealogy of “Yes We Can Can” BRUCE CURTIS Abstract I examine Raymond Williams’s concepts “structure of feeling” and “selective tradition” in an engagement with the novel technical-musical-cultural politics of the 2008 Barack Obama presidential election campaign. Williams hoped structure of feeling could be used to reveal the existence of pre-emergent, counter-hegemonic cultural forces, forces marginalized through selective tradition. In a genealogy of the Allen Toussaint composition, “Yes We Can Can,” which echoed a key campaign slogan and chant, I detail Toussaint’s ambiguous role in the gentrification of music and dance that descended from New Orleans’s commerce in pleasure. I show that pleasure commerce and struggles against racial segregation were intimately connected. I argue that Toussaint defanged rough subaltern music, but he also promoted a shift in the denotative and connotative uses of language and in the assignments of bodily energy, which Williams held to be evidence of a change in structure of feeling. It is the question of the counter-hegemonic potential of subaltern musical practice that joins Raymond Williams’s theoretical concerns and the implication of Allen Toussaint’s musical work in cultural politics. My address to the question is suggestive and interrogative rather than declarative and definitive. Barack Obama’s 2008 American presidential election and the post-election celebrations were the first to be conducted under the conditions of “web 2.0,” whose rapid spread from the mid-2000s is a historic “cultural break” similar in magnitude and consequence to the earlier generalization of print culture.1 In Stuart Hall’s terms, such breaks are moments in which the cultural conditions of political hegemony change.2 They are underpinned by changes in technological forces, in relations of production and communication. -

Your Free Copy

YOUR FREE COPY THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO LIFE, TRAVEL & ENTERTAINMENT IN ICELAND Issue 01 – January 8 - February 4 – 2010 www.grapevine.is + COMPLETE CITY LISTINGS - INSIDE! The Reykjavík Grapevine Issue 01 — 2010 2 Editorial | Haukur S Magnússon 2009 in Pictures JULIA STAPLES Art Director: Hörður Kristbjörnsson YOUR FREE COPY THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO LIFE, TRAVEL & ENTERTAINMENT IN ICELAND www.grapevine.is + Issue 01 – January 8 - February 4 – 2010 COMPLETE CITY LISTINGS - INSIDE! [email protected] Design: Jóhannes Kjartansson [email protected] Photographers: Hörður Sveinsson / hordursveinsson.com Julia Staples / juliastaples.com Sales Director: Aðalsteinn Jörundsson Cover llustration by: [email protected] Hugleikur Dagsson Guðmundur Rúnar Svansson [email protected] Printed by Landsprent ehf. in 25.000 copies. Distribution: [email protected] The Reykjavík Grapevine Proofreader: Hafnarstræti 15, 101 Reykjavík Jim Rice www.grapevine.is [email protected] Press releases: Published by Fröken ehf. [email protected] www.froken.is Submissions inquiries: Member of the Icelandic Travel Industry [email protected] Association - www.saf.is These images are from a series titled "Home". Subscription inquiries: +354 540 3605 / [email protected] They summon up feelings about a distant Editorial: General inquiries: [email protected] idea of home and one that is deteriorating. +354 540 3600 / [email protected] Haukur’s 19th Editorial They are all taken this past summer in Advertising: Founders: “No comment” Rhode Island, USA, one of the places that +354 540 3605 / [email protected] Hilmar Steinn Grétarsson, Publisher: was home to me in my adolescence. Hörður Kristbjörnsson, I have nothing to say for now. There +354 540 3601 / [email protected] Jón Trausti Sigurðarson, is enough editorialising in this issue JS Oddur Óskar Kjartansson, Publisher: Valur Gunnarsson already.