I Sing Because I'm Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Review: the Fan Who Knew Too Much - WSJ.Com

Book Review: The Fan Who Knew Too Much - WSJ.com http://online.wsj.com/article/SB1000142405270230390150457... Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit www.djreprints.com See a sample reprint in PDF format. Order a reprint of this article now BOOKSHELF Updated June 29, 2012, 5:30 p.m. ET The Queen of Soul's Long Reign By EDDIE DEAN One of the more indelible moments from the Obama inauguration was the spectacle of Aretha Franklin singing her gospel rendition of "My Country, 'Tis of Thee," as poignant to watch as it was painful to hear. Bundled in an overcoat, gloves and a Sunday-go-to-meeting hat with a jumbo ribbon bow, she struggled in the raw winter cold to kindle her time-ravaged voice, once one of the wonders of the modern world. The performance was less about hitting the high notes than striking a chord with the flock: Here was America's Church Lady come to bless her children. It's a role that the 70-year-old Ms. Franklin plays quite well at ceremonies of state and funerals and whenever the occasion demands. But she also enjoys a Saturday night out as the reigning Queen of Soul, as when she regaled a stadium crowd at WrestleMania 23 in 2007 in her hometown of Detroit. Such cameos run the risk of making her a kind of caricature—someone who has overstayed her welcome on the pop-culture stage and become, like Orson Welles in his later years, the honorary emblem of antiquated if revered Americana. -

Faces of Praise!: Photos and Gospel Inspirations to Encourage and Uplift (Hardback)

QQMH6WOLB25R // Book < Faces of Praise!: Photos and Gospel Inspirations to Encourage and Uplift (Hardback) Faces of Praise!: Ph otos and Gospel Inspirations to Encourage and Uplift (Hardback) Filesize: 1020.26 KB Reviews These sorts of pdf is the greatest publication readily available. It can be rally intriguing throgh looking at time. You can expect to like how the blogger publish this book. (Prof. Eric Kuvalis II) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GKVFEUMMYTQ5 // Book // Faces of Praise!: Photos and Gospel Inspirations to Encourage and Uplift (Hardback) FACES OF PRAISE!: PHOTOS AND GOSPEL INSPIRATIONS TO ENCOURAGE AND UPLIFT (HARDBACK) To download Faces of Praise!: Photos and Gospel Inspirations to Encourage and Upli (Hardback) PDF, make sure you follow the web link beneath and download the file or have accessibility to additional information which might be in conjuction with FACES OF PRAISE!: PHOTOS AND GOSPEL INSPIRATIONS TO ENCOURAGE AND UPLIFT (HARDBACK) ebook. Time Warner Trade Publishing, United States, 2017. Hardback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. This full-color photo gi book that turns chart-topping contemporary gospel music into Bible-based devotions is a three-way blessing for readers: a perfect companion to favorite gospel recordings, an encouraging daily devotional and a unique photo collection.Here are never-before-seen four-color images of the top 60 contemporary gospel artists taken on stage, as they led worship concerts. B. Jerey Grant-Clark met with, worked alongside, and photographed all these gospel icons-- Donnie McClurkin, CeCe Winans, Kirk Franklin, the award winning duo Mary Mary and many more--during his decades-long music career. He joins author Carol M. -

Southern Black Gospel Music: Qualitative Look at Quartet Sound

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN BLACK GOSPEL MUSIC: QUALITATIVE LOOK AT QUARTET SOUND DURING THE GOSPEL ‘BOOM’ PERIOD OF 1940-1960 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY BY BEATRICE IRENE PATE LYNCHBURG, V.A. April 2014 1 Abstract The purpose of this work is to identify features of southern black gospel music, and to highlight what makes the music unique. One goal is to present information about black gospel music and distinguishing the different definitions of gospel through various ages of gospel music. A historical accounting for the gospel music is necessary, to distinguish how the different definitions of gospel are from other forms of gospel music during different ages of gospel. The distinctions are important for understanding gospel music and the ‘Southern’ gospel music distinction. The quartet sound was the most popular form of music during the Golden Age of Gospel, a period in which there was significant growth of public consumption of Black gospel music, which was an explosion of black gospel culture, hence the term ‘gospel boom.’ The gospel boom period was from 1940 to 1960, right after the Great Depression, a period that also included World War II, and right before the Civil Rights Movement became a nationwide movement. This work will evaluate the quartet sound during the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s, which will provide a different definition for gospel music during that era. Using five black southern gospel quartets—The Dixie Hummingbirds, The Fairfield Four, The Golden Gate Quartet, The Soul Stirrers, and The Swan Silvertones—to define what southern black gospel music is, its components, and to identify important cultural elements of the music. -

OAG Hearing on Interactions Between NYPD and the General Public Submitted Written Testimony

OAG Hearing on Interactions Between NYPD and the General Public Submitted Written Testimony Tahanie Aboushi | New York, New York I am counsel for Dounya Zayer, the protestor who was violently shoved by officer D’Andraia and observed by Commander Edelman. I would like to appear with Dounya to testify at this hearing and I will submit written testimony at a later time but well before the June 15th deadline. Thank you. Marissa Abrahams | South Beach Psychiatric Center | Brooklyn, New York As a nurse, it has been disturbing to see first-hand how few NYPD officers (present en masse at ALL peaceful protests) are wearing the face masks that we know are preventing the spread of COVID-19. Demonstrators are taking this extremely seriously and I saw NYPD literally laugh in the face of a protester who asked why they do not. It is negligent and a blatant provocation -especially in the context of the over-policing of Black and Latinx communities for social distancing violations. The complete disregard of the NYPD for the safety of the people they purportedly protect and serve, the active attacks with tear gas and pepper spray in the midst of a respiratory pandemic, is appalling and unacceptable. Aaron Abrams | Brooklyn, New York I will try to keep these testimonies as precise as possible since I know your office likely has hundreds, if not thousands to go through. Three separate occasions highlighted below: First Incident - May 30th - Brooklyn - peaceful protestors were walking from Prospect Park through the streets early in the day. At one point, police stopped to block the street and asked that we back up. -

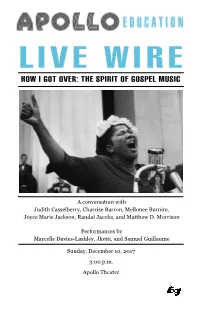

View the Program Book for How I Got Over

A conversation with Judith Casselberry, Charrise Barron, Mellonee Burnim, Joyce Marie Jackson, Randal Jacobs, and Matthew D. Morrison Performances by Marcelle Davies-Lashley, Jhetti, and Samuel Guillaume Sunday, December 10, 2017 3:00 p.m. Apollo Theater Front Cover: Mahalia Jackson; March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 1957 LIVE WIRE: HOW I GOT OVER - THE SPIRIT OF GOSPEL MUSIC In 1963, when Mahalia Jackson sang “How I Got Over” before 250,000 protesters at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, she epitomized the sound and sentiment of Black Americans one hundred years after Emancipation. To sing of looking back to see “how I got over,” while protesting racial violence and social, civic, economic, and political oppression, both celebrated victories won and allowed all to envision current struggles in the past tense. Gospel is the good news. Look how far God has brought us. Look at where God will take us. On its face, the gospel song composed by Clara Ward in 1951, spoke to personal trials and tribulations overcome by the power of Jesus Christ. Black gospel music, however, has always occupied a space between the push to individualistic Christian salvation and community liberation in the context of an unjust society— a declaration of faith by the communal “I”. From its incubation at the turn of the 20th century to its emergence as a genre in the 1930s, gospel was the sound of Black people on the move. People with purpose, vision, and a spirit of experimentation— clear on what they left behind, unsure of what lay ahead. -

Simply Folk Sing-Along 2018 If I Had a Hammer If I Had a Hammer, I'd Hammer in the Morning, I'd Hammer in the Evening, All Over

Simply Folk Sing-Along 2018 If I Had a Hammer If I had a hammer, I'd hammer in the morning, I'd hammer in the evening, all over this land I'd hammer out danger, I'd hammer out a warning I'd hammer out love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land If I had a bell, I'd ring it in the morning, I'd ring it in the evening, all over this land I'd ring out danger, I'd ring out a warning I'd ring out love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land If I had a song, I'd sing it in the morning, I'd sing it in the evening, all over this land I'd sing out danger, I'd sing out a warning I'd sing out love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land Well I've got a hammer, and I've got a bell, and I've got a song to sing, all over this land It's the hammer of justice, it's the bell of freedom It's the song about love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land You Are My Sunshine The other night dear as I lay sleeping, I dreamed I held you in my arms, But when I woke dear I was mistaken, and I hung my head and I cried You are my sunshine, my only sunshine, you make me happy when skies are gray, You'll never know dear, how much I love you, please don't take my sunshine away I'll always love you and make you happy, if you will only say the same, But if you leave me and love another, you’ll regret it all someday You told me once dear, you really loved me, and no one could come between, But now you've left me to love another, you have shattered all of my dreams In all my dreams, dear, you seem to leave me; when I awake my poor heart pains So won’t you come back and make me happy, I’ll forgive, dear, I’ll take all the blame City of New Orleans Riding on the City of New Orleans, Illinois Central Monday morning rail Fifteen cars and fifteen restless riders, three conductors and twenty-five sacks of mail. -

The Production of Gospel Music: an Ethnographic Study of Studio-Recorded Music in Bellville, Cape Town

The production of gospel music: An ethnographic study of studio-recorded music in Bellville, Cape Town A mini thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology Robin L. Thompson Department of Anthropology and Sociology University of the Western Cape November 2015 Supervisor: Professor Heike Becker Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................ ......................................................... i Declaration ................................................................ ................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................... iii CHAPTER 1: Introduction ...........................................................................................................................1 1.1 The prevalence of Pentecostalism and music in Christian households, churches and media in Cape Town .............................................................................................................................................................4 1.2 Rethinking the idea of genre through ‘Pentecospel’ music ....................................................................8 1.3 Going forth ............................................................................................................................................10 1.4 Chapter Outline -

Conflict in Pentecostal Churches: the Case of Christian Church International, Kiria-Ini Town, Murang`A County, Kenya by Daniel M

CONFLICT IN PENTECOSTAL CHURCHES: THE CASE OF CHRISTIAN CHURCH INTERNATIONAL, KIRIA-INI TOWN, MURANG`A COUNTY, KENYA BY DANIEL MAINA GATHUKI C50/CE/11020/06 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY NOVEMBER 2015 ii DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University or any other award. ……………………………… ………………………… Signature Date Daniel Maina Gathuki (C50/CE/11020/06) Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies SUPERVISORS This thesis has been submitted with our approval as University Supervisors. …………………………… ………………………… Signature Date Dr. Margaret Gecaga Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies ……………………………… ……………………… Signature Date Dr. Josephine Gitome Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies iii DEDICATION To my wife Mary Waithera Maina and our children Morris, Mark and Maxwell for their unwavering love and support. Their endurance was a great encouragement. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT To God be the glory. His grace was sufficient throughout this study. This study would not have come to fruition without the guidance, suggestions, insights and inspirations from my dedicated supervisors Dr. Margaret Gecaga and Dr. Josephine Gitome. I thank them for their tireless effort, patience and contribution to this work. I am equally thankful to Dr. Zacharia Samita for his rich academic input into this work: He referred me to relevant sources that enriched this study. Special thanks go to my research assistant Mr. Paul W. Kariuki for his diligence and patience that saw me collect the required data. I am also greatly indebted to all my respondents, especially Bishop Duncan Mbogo (General Secretary of Christian Church International Kenya), Rev. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

The Formation and Early Development of the Church of God in Christ

THE INTERDENOMINATIONAL THEOLOGICAL CENTER THE FORMATION AND EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF THE CHURCH OF GOD IN CHRIST BY OLIVER J. HANEY, JR. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Divinity degree Dr. Thomas J. Pugh, Advisor Date, April 12, 1969 TABLE OP CONTENTS Page No. 1. Introduction 11. The Founding Fathers 111. Events Incidental in the Beginning of the Church of God in Christ 10 IV. The Formation of the Church of God in Christ 14 V. The Emerging Church of God in Christ 23 VI. Summary and Conclusion 27 Vll. Bibliography Dedication To my wife, LaVerne, for her devotion and assistance during my Seminary career. - f^.i,i%S, Preface The Church of God in Christ was organized in the latter 1880's. Since that time, it has grown tremendously. It has also made an outstanding contribution to the development of a sense of moral duty and spiritual responsibility in the people of the world, and it takes its place among other Protestant denominations of the world. Even though the above cannot be denied, I find it astonishing and disappointing that the truth about the Church of God in Christ as to it's historical beginning, practices and its doctrines are actually known by so few. Therefore, I feel it necessary for me to make known the history of the Church of God in Christ, and have assumed that task in the essay. It is hoped that many of the misunderstandings about the Church can be made clear. It is also my aim that those who do not know about the Church,may through this essay become ac quainted with it, and that those who are already familiar with it, may be further enlightened. -

Pg0140 Layout 1

New Releases HILLSONG UNITED: LIVE IN MIAMI Table of Contents Giving voice to a generation pas- Accompaniment Tracks . .14, 15 sionate about God, the modern Bargains . .20, 21, 38 rock praise & worship band shares 22 tracks recorded live on their Collections . .2–4, 18, 19, 22–27, sold-out Aftermath Tour. Includes 31–33, 35, 36, 38, 39 the radio single “Search My Heart,” “Break Free,” “Mighty to Save,” Contemporary & Pop . .6–9, back cover “Rhythms of Grace,” “From the Folios & Songbooks . .16, 17 Inside Out,” “Your Name High,” “Take It All,” “With Everything,” and the Gifts . .back cover tour theme song. Two CDs. Hymns . .26, 27 $ 99 KTCD23395 Retail $14.99 . .CBD Price12 Inspirational . .22, 23 Also available: Instrumental . .24, 25 KTCD28897 Deluxe CD . 19.99 15.99 KT623598 DVD . 14.99 12.99 Kids’ Music . .18, 19 Movie DVDs . .A1–A36 he spring and summer months are often New Releases . .2–5 Tpacked with holidays, graduations, celebra- Praise & Worship . .32–37 tions—you name it! So we had you and all your upcoming gift-giving needs in mind when we Rock & Alternative . .10–13 picked the products to feature on these pages. Southern Gospel, Country & Bluegrass . .28–31 You’ll find $5 bargains on many of our best-sell- WOW . .39 ing albums (pages 20 & 21) and 2-CD sets (page Search our entire music and film inventory 38). Give the special grad in yourConGRADulations! life something unique and enjoyable with the by artist, title, or topic at Christianbook.com! Class of 2012 gift set on the back cover. -

Final Nominations List

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. FINAL NOMINATIONS LIST THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. Final Nominations List 60th Annual GRAMMY® Awards For recordings released during the Eligibility Year October 1, 2016 through September 30, 2017 Note: More or less than 5 nominations in a category is the result of ties. General Field Category 1 Category 2 Record Of The Year Album Of The Year Award to the Artist and to the Producer(s), Recording Engineer(s) Award to Artist(s) and to Featured Artist(s), Songwriter(s) of new material, and/or Mixer(s) and mastering engineer(s), if other than the artist. Producer(s), Recording Engineer(s), Mixer(s) and Mastering Engineer(s) credited with at least 33% playing time of the album, if other than Artist. 1. REDBONE Childish Gambino 1. "AWAKEN, MY LOVE!" Childish Gambino Donald Glover & Ludwig Goransson, producers; Donald Donald Glover & Ludwig Goransson, producers; Bryan Carrigan, Glover, Ludwig Goransson, Riley Mackin & Ruben Rivera, Chris Fogel, Donald Glover, Ludwig Goransson, Riley Mackin & engineers/mixers; Bernie Grundman, mastering engineer Ruben Rivera, engineers/mixers; Donald Glover & Ludwig 2. DESPACITO Goransson, songwriters; Bernie Grundman, mastering engineer Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Featuring Justin Bieber 2. 4:44 Josh Gudwin, Mauricio Rengifo & Andrés Torres, JAY-Z producers; Josh Gudwin, Jaycen Joshua, Chris ‘TEK’ JAY-Z & No I.D., producers; Jimmy Douglass & Gimel "Young O’Ryan, Mauricio Rengifo, Juan G Rivera “Gaby Music,” Guru" Keaton, engineers/mixers; Shawn Carter & Dion Wilson, Luis “Salda” Saldarriaga & Andrés Torres, songwriters; Dave Kutch, mastering engineer engineers/mixers; Dave Kutch, mastering engineer 3.