Paper for B(&N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

Mahalia Jackson (B

Mahalia Jackson (b. 10/26/11, d. 1/27/72) was born Mahala Jackson in the Uptown neighborhood of New Orleans, Louisiana, and began singing at the Mount Mariah Baptist Church there at the age of 4. She grew up in a very poor household, which contained thirteen people and a dog in a three-room dwelling. Her stage name “Mahalia” stems from her childhood nickname “Halie”. In 1927, at the age of 16 she moved to Chicago, Illinois in the midst of the Great Migration. She intended to study nursing, but after joining a local church she became a member of the Johnson Gospel Singers. She performed with the group for a number of years. She then started working with Thomas A. Dorsey, the gospel composer of “Precious Lord, Take My Hand”, and the two performed around the U.S., which helped tremendously in cultivating a future audience for her. While she made some recordings in the 1930’s, her first major success came with “Move On Up A Little Higher” in 1947, which sold millions of copies and became the highest selling gospel single in history. Her career blossomed, and on October 4, 1950 she became the first gospel singer to perform at Carnegie Hall, and she did so to a racially integrated audience. Also in the 1950’s she became an international star, being especially popular in France and Norway. Back at home, she made her debut on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1956, and appeared with Duke Ellington and his Orchestra at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1958. -

Book Review: the Fan Who Knew Too Much - WSJ.Com

Book Review: The Fan Who Knew Too Much - WSJ.com http://online.wsj.com/article/SB1000142405270230390150457... Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit www.djreprints.com See a sample reprint in PDF format. Order a reprint of this article now BOOKSHELF Updated June 29, 2012, 5:30 p.m. ET The Queen of Soul's Long Reign By EDDIE DEAN One of the more indelible moments from the Obama inauguration was the spectacle of Aretha Franklin singing her gospel rendition of "My Country, 'Tis of Thee," as poignant to watch as it was painful to hear. Bundled in an overcoat, gloves and a Sunday-go-to-meeting hat with a jumbo ribbon bow, she struggled in the raw winter cold to kindle her time-ravaged voice, once one of the wonders of the modern world. The performance was less about hitting the high notes than striking a chord with the flock: Here was America's Church Lady come to bless her children. It's a role that the 70-year-old Ms. Franklin plays quite well at ceremonies of state and funerals and whenever the occasion demands. But she also enjoys a Saturday night out as the reigning Queen of Soul, as when she regaled a stadium crowd at WrestleMania 23 in 2007 in her hometown of Detroit. Such cameos run the risk of making her a kind of caricature—someone who has overstayed her welcome on the pop-culture stage and become, like Orson Welles in his later years, the honorary emblem of antiquated if revered Americana. -

The Attucks Theater September 4, 2020 | Source: Theater/ Words by Penny Neef

Spotlight: The Attucks Theater September 4, 2020 | Source: http://spotlightnews.press/index.php/2020/09/04/spotlight-the-attucks- theater/ Words by Penny Neef. Images as credited. Feature image by Mike Penello. In the early 20th century, segregation was a fact of life for African Americans in the South. It became a matter of law in 1926. In 1919, a group of African Americans from Norfolk and Portsmouth met to develop a cultural/business center in Norfolk where the black community “could be treated with dignity and respect.” The “Twin Cities Amusement Corporation” envisioned something like a modern-day town center. The businessmen obtained funding from black owned financial institutions in Hampton Roads. Twin Cities designed and built a movie theater/ retail/ office complex at the corner of Church Street and Virginia Beach Boulevard in Norfolk. Photo courtesy of the family of Harvey Johnson The businessmen chose 25-year-old architect Harvey Johnson to design a 600-seat “state of the art” theater with balconies and an orchestra pit. The Attucks Theatre is the only surviving theater in the United States that was designed, financed and built by African Americans. The Attucks was named after Crispus Attucks, a stevedore of African and Native American descent. He was the first patriot killed in the Revolutionary War at the Boston Massacre of 1770. The theatre featured a stage curtain with a dramatic depiction of the death of Crispus Attucks. Photo by Scott Wertz. The Attucks was an immediate success. It was known as the “Apollo Theatre of the South.” Legendary performers Cab Calloway, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn, Nat King Cole, and B.B. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Women, Gender, and Music During Wwii a Thesis

EDINBORO UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PITCHING PATRIARCHY: WOMEN, GENDER, AND MUSIC DURING WWII A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, POLITICS, LANGUAGES, AND CULTURES FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS SOCIAL SCIENCES-HISTORY BY SARAH N. GAUDIOSO EDINBORO, PENNSYLVANIA APRIL 2018 1 Pitching Patriarchy: Women, Music, and Gender During WWII by Sarah N. Gaudioso Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Master of Social Sciences in History ApprovedJjy: Chairperson, Thesis Committed Edinbqro University of Pennsylvania Committee Member Date / H Ij4 I tg Committee Member Date Formatted with the 8th Edition of Kate Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses and Dissertations. i S C ! *2— 1 Copyright © 2018 by Sarah N. Gaudioso All rights reserved ! 1 !l Contents INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: HISTORIOGRAPHY 5 CHAPTER 2: WOMEN IN MUSIC DURING WORLD WAR II 35 CHAPTER 3: AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN AND MUSIC DURING THE WAR.....84 CHAPTER 4: COMPOSERS 115 CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSIONS 123 BIBLIOGRAPHY 128 Gaudioso 1 INTRODUCTION A culture’s music reveals much about its values, and music in the World War II era was no different. It served to unite both military and civilian sectors in a time of total war. Annegret Fauser explains that music, “A medium both permeable and malleable was appropriated for numerous war related tasks.”1 When one realizes this principle, it becomes important to understand how music affected individual segments of American society. By examining women’s roles in the performance, dissemination, and consumption of music, this thesis attempts to position music as a tool in perpetuating the patriarchal gender relations in America during World War II. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

Southern Black Gospel Music: Qualitative Look at Quartet Sound

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN BLACK GOSPEL MUSIC: QUALITATIVE LOOK AT QUARTET SOUND DURING THE GOSPEL ‘BOOM’ PERIOD OF 1940-1960 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY BY BEATRICE IRENE PATE LYNCHBURG, V.A. April 2014 1 Abstract The purpose of this work is to identify features of southern black gospel music, and to highlight what makes the music unique. One goal is to present information about black gospel music and distinguishing the different definitions of gospel through various ages of gospel music. A historical accounting for the gospel music is necessary, to distinguish how the different definitions of gospel are from other forms of gospel music during different ages of gospel. The distinctions are important for understanding gospel music and the ‘Southern’ gospel music distinction. The quartet sound was the most popular form of music during the Golden Age of Gospel, a period in which there was significant growth of public consumption of Black gospel music, which was an explosion of black gospel culture, hence the term ‘gospel boom.’ The gospel boom period was from 1940 to 1960, right after the Great Depression, a period that also included World War II, and right before the Civil Rights Movement became a nationwide movement. This work will evaluate the quartet sound during the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s, which will provide a different definition for gospel music during that era. Using five black southern gospel quartets—The Dixie Hummingbirds, The Fairfield Four, The Golden Gate Quartet, The Soul Stirrers, and The Swan Silvertones—to define what southern black gospel music is, its components, and to identify important cultural elements of the music. -

Aint Gonna Study War No More / Down by the Riverside

The Danish Peace Academy 1 Holger Terp: Aint gonna study war no more Ain't gonna study war no more By Holger Terp American gospel, workers- and peace song. Author: Text: Unknown, after 1917. Music: John J. Nolan 1902. Alternative titles: “Ain' go'n' to study war no mo'”, “Ain't gonna grieve my Lord no more”, “Ain't Gwine to Study War No More”, “Down by de Ribberside”, “Down by the River”, “Down by the Riverside”, “Going to Pull My War-Clothes” and “Study war no more” A very old spiritual that was originally known as Study War No More. It started out as a song associated with the slaves’ struggle for freedom, but after the American Civil War (1861-65) it became a very high-spirited peace song for people who were fed up with fighting.1 And the folk singer Pete Seeger notes on the record “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy and Other Love Songs”, that: "'Down by the Riverside' is, of course, one of the oldest of the Negro spirituals, coming out of the South in the years following the Civil War."2 But is the song as we know it today really as old as it is claimed without any sources? The earliest printed version of “Ain't gonna study war no more” is from 1918; while the notes to the song were published in 1902 as music to a love song by John J. Nolan.3 1 http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/grovemusic/spirituals,_hymns,_gospel_songs.htm 2 Thanks to Ulf Sandberg, Sweden, for the Pete Seeger quote. -

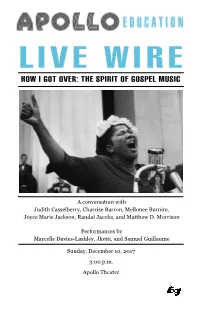

View the Program Book for How I Got Over

A conversation with Judith Casselberry, Charrise Barron, Mellonee Burnim, Joyce Marie Jackson, Randal Jacobs, and Matthew D. Morrison Performances by Marcelle Davies-Lashley, Jhetti, and Samuel Guillaume Sunday, December 10, 2017 3:00 p.m. Apollo Theater Front Cover: Mahalia Jackson; March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 1957 LIVE WIRE: HOW I GOT OVER - THE SPIRIT OF GOSPEL MUSIC In 1963, when Mahalia Jackson sang “How I Got Over” before 250,000 protesters at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, she epitomized the sound and sentiment of Black Americans one hundred years after Emancipation. To sing of looking back to see “how I got over,” while protesting racial violence and social, civic, economic, and political oppression, both celebrated victories won and allowed all to envision current struggles in the past tense. Gospel is the good news. Look how far God has brought us. Look at where God will take us. On its face, the gospel song composed by Clara Ward in 1951, spoke to personal trials and tribulations overcome by the power of Jesus Christ. Black gospel music, however, has always occupied a space between the push to individualistic Christian salvation and community liberation in the context of an unjust society— a declaration of faith by the communal “I”. From its incubation at the turn of the 20th century to its emergence as a genre in the 1930s, gospel was the sound of Black people on the move. People with purpose, vision, and a spirit of experimentation— clear on what they left behind, unsure of what lay ahead. -

From King Records Month 2018

King Records Month 2018 = Unedited Tweets from Zero to 180 Aug. 3, 2018 Zero to 180 is honored to be part of this year's celebration of 75 Years of King Records in Cincinnati and will once again be tweeting fun facts and little known stories about King Records throughout King Records Month in September. Zero to 180 would like to kick off things early with a tribute to King session drummer Philip Paul (who you've heard on Freddy King's "Hideaway") that is PACKED with streaming audio links, images of 45s & LPs from around the world, auction prices, Billboard chart listings and tons of cool history culled from all the important music historians who have written about King Records: “Philip Paul: The Pulse of King” https://www.zeroto180.org/?p=32149 Aug. 22, 2018 King Records Month is just around the corner - get ready! Zero to 180 will be posting a new King history piece every 3 days during September as well as October. There will also be tweeting lots of cool King trivia on behalf of Xavier University's 'King Studios' historic preservation collaborative - a music history explosion that continues with this baseball-themed celebration of a novelty hit that dominated the year 1951: LINK to “Chew Tobacco Rag” Done R&B (by Lucky Millinder Orchestra) https://www.zeroto180.org/?p=27158 Aug. 24, 2018 King Records helped pioneer the practice of producing R&B versions of country hits and vice versa - "Chew Tobacco Rag" (1951) and "Why Don't You Haul Off and Love Me" (1949) being two examples of such 'crossover' marketing. -

Announcing the 2019 Scholastic Art & Writing

ANNOUNCING THE 2019 SCHOLASTIC ART & WRITING AWARDS NATIONAL MEDALISTS! Student & Educator National Medalists: Please log into your account at artandwriting.org/login to review required next steps to accept your award(s). Important Note for Educators: If one of your students is a National Medalist listed below, but you do not have a Scholastic Awards account or you do not see any information about your student's Award in your account, please email [email protected]. In your email, be sure to include the title and work ID number as listed on this document. The following list is sorted by the student's school state and then by last name. Last First Grade School City State Title National Awards Work ID Category Carr Sally 12 Home School Wasilla AK Portraiture Silver Medal with 13183357 Art Portfolio Distinction Carr Sally 12 Home School Wasilla AK Elizabeth Gold Medal, 13387176 Ceramics & Glass American Visions Medal Laird Anna J. 11 Home School Cordova AK Blood of Mary Silver Medal 13224628 Short Story Altubuh Dalia 12 Bob Jones High School Madison AL Me As Human Silver Medal 13199019 Digital Art Altubuh Dalia 12 Bob Jones High School Madison AL LITTLE BOY and FAT MAN Silver Medal 13223746 Poetry Brown Maggie 10 Bob Jones High School Madison AL Kintsugi and Other Poems Gold Medal 13098325 Poetry Dewberry Lauryn- 11 Alabama School of Fine Arts Birmingham AL My Grandparents, In Love Silver Medal 13082772 Poetry Elizabeth Fernandez Kristine 11 Sparkman High School Harvest AL Masked Silver Medal 13082442 Photography Gardner Abigail 11 Alabama