Steve Waksman [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

B2 Woodstock – the Greatest Music Event in History LIU030

B2 Woodstock – The Greatest Music Event in History LIU030 Choose the best option for each blank. The Woodstock Festival was a three-day pop and rock concert that turned out to be the most popular music (1) _________________ in history. It became a symbol of the hippie (2) _________________ of the 1960s. Four young men organized the festival. The (3) _________________ idea was to stage a concert that would (4) _________________ enough money to build a recording studio for young musicians at Woodstock, New York. Young visitors on their way to Woodstock At first many things went wrong. People didn't want Image: Ric Manning / CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) any hippies and drug (5) _________________ coming to the original location. About 2 months before the concert a new (6) _________________ had to be found. Luckily, the organizers found a 600-acre large dairy farm in Bethel, New York, where the concert could (7) _________________ place. Because the venue had to be changed not everything was finished in time. The organizers (8) _________________ about 50,000 people, but as the (9) _________________ came nearer it became clear that far more people wanted to be at the event. A few days before the festival began hundreds of thousands of pop and rock fans were on their (10) _________________ to Woodstock. There were not enough gates where tickets were checked and fans made (11) _________________ in the fences, so lots of people just walked in. About 300,000 to 500,000 people were at the concert. The event caused a giant (12) _________________ jam. -

Universidade Federal Do Rio De Janeiro Centro De Filosofia E Ciências Humanas Escola De Comunicação

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO CENTRO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO A ECONOMIA DA EXPERIÊNCIA NO CONTEXTO DOS FESTIVAIS DE MÚSICA Inacio Faulhaber Martins Martinelli Rio de Janeiro/RJ 2013 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO CENTRO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO A ECONOMIA DA EXPERIÊNCIA NO CONTEXTO DOS FESTIVAIS DE MÚSICA Inacio Faulhaber Martins Martinelli Monografia de graduação apresentada à Escola de Comunicação da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Bacharel em Comunicação Social, Habilitação em Publicidade e Propaganda. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Micael Maiolino Herschmann Rio de Janeiro/RJ 2013 MARTINELLI, Inacio Faulhaber Martins. A Economia da Experiência no Contexto dos Festivais de Música/ Inacio Faulhaber Martins Martinelli – Rio de Janeiro; UFRJ/ECO, 2013. xi, 63 f. Monografia (graduação em Comunicação) – Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Escola de Comunicação, 2013. Orientação: Micael Maiolino Herschmann 1. Festivais de música. 2. Economia da Experiência. 3. Entretenimento. I. HERSCHMANN, Micael Maiolino II. ECO/UFRJ III. Publicidade e Propaganda IV. A Economia da Experiência no Contexto dos Festivais de Música. Dedico essa monografia aos meus pais, Ivan e Leci, por se esforçarem ao máximo para que os seus quatro filhos tivessem uma educação de qualidade. AGRADECIMENTO Gostaria de agradecer, primeiramente, à minha família, pelo apoio incondicional sempre que eu precisei. Meus pais, Ivan e Leci, além de meus três irmãos, Ivan, Isabel e Italo, não sei o que seria de mim sem vocês. Ao professor Micael Herschmann, um “muito obrigado” pela colaboração nesse desgastante processo e por abraçar a minha idéia desde o princípio. -

Grunge Is Dead Is an Oral History in the Tradition of Please Kill Me, the Seminal History of Punk

THE ORAL SEATTLE ROCK MUSIC HISTORY OF GREG PRATO WEAVING TOGETHER THE DEFINITIVE STORY OF THE SEATTLE MUSIC SCENE IN THE WORDS OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE THERE, GRUNGE IS DEAD IS AN ORAL HISTORY IN THE TRADITION OF PLEASE KILL ME, THE SEMINAL HISTORY OF PUNK. WITH THE INSIGHT OF MORE THAN 130 OF GRUNGE’S BIGGEST NAMES, GREG PRATO PRESENTS THE ULTIMATE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO A SOUND THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER. THE GRUNGE MOVEMENT MAY HAVE THRIVED FOR ONLY A FEW YEARS, BUT IT SPAWNED SOME OF THE GREATEST ROCK BANDS OF ALL TIME: PEARL JAM, NIRVANA, ALICE IN CHAINS, AND SOUNDGARDEN. GRUNGE IS DEAD FEATURES THE FIRST-EVER INTERVIEW IN WHICH PEARL JAM’S EDDIE VEDDER WAS WILLING TO DISCUSS THE GROUP’S HISTORY IN GREAT DETAIL; ALICE IN CHAINS’ BAND MEMBERS AND LAYNE STALEY’S MOM ON STALEY’S DRUG ADDICTION AND DEATH; INSIGHTS INTO THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT AND OFT-OVERLOOKED BUT HIGHLY INFLUENTIAL SEATTLE BANDS LIKE MOTHER LOVE BONE, THE MELVINS, SCREAMING TREES, AND MUDHONEY; AND MUCH MORE. GRUNGE IS DEAD DIGS DEEP, STARTING IN THE EARLY ’60S, TO EXPLAIN THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT GAVE WAY TO THE MUSIC. THE END RESULT IS A BOOK THAT INCLUDES A WEALTH OF PREVIOUSLY UNTOLD STORIES AND FRESH INSIGHT FOR THE LONGTIME FAN, AS WELL AS THE ESSENTIALS AND HIGHLIGHTS FOR THE NEWCOMER — THE WHOLE UNCENSORED TRUTH — IN ONE COMPREHENSIVE VOLUME. GREG PRATO IS A LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, WHO REGULARLY WRITES FOR ALL MUSIC GUIDE, BILLBOARD.COM, ROLLING STONE.COM, RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE, AND CLASSIC ROCK MAGAZINE. -

ANDERTON Music Festival Capitalism

1 Music Festival Capitalism Chris Anderton Abstract: This chapter adds to a growing subfield of music festival studies by examining the business practices and cultures of the commercial outdoor sector, with a particular focus on rock, pop and dance music events. The events of this sector require substantial financial and other capital in order to be staged and achieve success, yet the market is highly volatile, with relatively few festivals managing to attain longevity. It is argued that these events must balance their commercial needs with the socio-cultural expectations of their audiences for hedonistic, carnivalesque experiences that draw on countercultural understanding of festival culture (the countercultural carnivalesque). This balancing act has come into increased focus as corporate promoters, brand sponsors and venture capitalists have sought to dominate the market in the neoliberal era of late capitalism. The chapter examines the riskiness and volatility of the sector before examining contemporary economic strategies for risk management and audience development, and critiques of these corporatizing and mainstreaming processes. Keywords: music festival; carnivalesque; counterculture; risk management; cool capitalism A popular music festival may be defined as a live event consisting of multiple musical performances, held over one or more days (Shuker, 2017, 131), though the connotations of 2 the word “festival” extend much further than this, as I will discuss below. For the purposes of this chapter, “popular music” is conceived as music that is produced by contemporary artists, has commercial appeal, and does not rely on public subsidies to exist, hence typically ranges from rock and pop through to rap and electronic dance music, but excludes most classical music and opera (Connolly and Krueger 2006, 667). -

Open'er Festival

SHORTLISTED NOMINEES FOR THE EUROPEAN FESTIVAL AWARDS 2019 UNVEILED GET YOUR TICKET NOW With the 11th edition of the European Festival Awards set to take place on January 15th in Groningen, The Netherlands, we’re announcing the shortlists for 14 of the ceremony’s categories. Over 350’000 votes have been cast for the 2019 European Festival Awards in the main public categories. We’d like to extend a huge thank you to all of those who applied, voted, and otherwise participated in the Awards this year. Tickets for the Award Ceremony at De Oosterpoort in Groningen, The Netherlands are already going fast. There are two different ticket options: Premium tickets are priced at €100, and include: • Access to the cocktail hour with drinks from 06.00pm – 06.45pm • Three-course sit down Dinner with drinks at 07.00pm – 09.00pm • A seat at a table at the EFA awards show at 09.30pm – 11.15pm • Access to the after-show party at 00.00am – 02.00am – Venue TBD Tribune tickets are priced at €30 and include access to the EFA awards show at 09.30pm – 11.15pm (no meal or extras included). Buy Tickets Now without further ado, here are the shortlists: The Brand Activation Award Presented by: EMAC Lowlands (The Netherlands) & Rabobank (Brasserie 2050) Open’er Festival (Poland) & Netflix (Stranger Things) Øya Festivalen (Norway) & Fortum (The Green Rider) Sziget Festival (Hungary) & IBIS (IBIS Music) Untold (Romania) & KFC (Haunted Camping) We Love Green (France) & Back Market (Back Market x We Love Green Circular) European Festival Awards, c/o YOUROPE, Heiligkreuzstr. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. August 3, 2020 to Sun. August 9, 2020

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. August 3, 2020 to Sun. August 9, 2020 Monday August 3, 2020 7:30 PM ET / 4:30 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Rock Legends TrunkFest with Eddie Trunk Cream - Fronted by Eric Clapton, Cream was the prototypical power trio, playing a mix of blues, Sturgis Motorycycle Rally - Eddie heads to South Dakota for the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally at the rock and psychedelia while focusing on chunky riffs and fiery guitar solos. In a mere three years, Buffalo Chip. Special guests George Thorogood and Jesse James Dupree join Eddie as he explores the band sold 15 million records, played to SRO crowds throughout the U.S. and Europe, and one of America’s largest gatherings of motorcycle enthusiasts. redefined the instrumentalist’s role in rock. 8:30 AM ET / 5:30 AM PT Premiere Rock & Roll Road Trip With Sammy Hagar 8:00 PM ET / 5:00 PM PT Mardi Gras - The “Red Rocker,” Sammy Hagar, heads to one of the biggest parties of the year, At Home and Social Mardi Gras. Join Sammy Hagar as he takes to the streets of New Orleans, checks out the Nuno Bettencourt & Friends - At Home and Social presents exclusive live performances, along world-famous floats, performs with Trombone Shorty, and hangs out with celebrity chef Emeril with intimate interviews, fun celebrity lifestyle pieces and insightful behind-the-scenes anec- Lagasse. dotes from our favorite music artists. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT Premiere The Big Interview Special Edition 9:00 PM ET / 6:00 PM PT Keith Urban - Dan catches up with country music superstar Keith Urban on his “Ripcord” tour. -

II «Grande Crollo » Di Lira E Borsa

UNIPOL ASSICURAZIONI Sicuramente con te Sicuramente con te ANNO 71. N. 190 SPED. IN ABB. POST. - 50% - ROMA SABATO 13 AGOSTO 1994 - L 1.300 MULL zm La nostra moneta fino a 1.030 sul marco. Il Cavaliere: sono in guerra. I Progressisti: venga subito in Parlamento II «grande crollo » di lira e Borsa L'esponente Berlusconi: va tutto bene Confindustria Fumagalli: «Non c'è Dini attacca Bankitalia fiducia nell'Italia» m Lira, Borsa, titoli di stato in ca duta libera. La peggiore giornata . BRUNO dai tempi della «tempesta moneta UGOLINI ria» di due anni fa. Mentre Berlu A PAGINA 2 Il problema Due anni sconi preparava il suo «messaggio di ottimismo» agli italiani sui mer cati finanziari l'azienda Italia ha • buttati via combattuto e perso una sanguino sa battaglia. Il marco è volato a 1.030,5 lire, per finire poi nella «fo Vicepresidente tografia» di. Bankitalia a quota Cariplo LUIQIBERLINGUER VINCENZO VISCO 1.026,8: record negativo assoluto. La Borsa ha chiuso per l'ottava vol Talamona: UELCHE .sta OLO POCHI gior ta consecutiva in calo, perdendo succedendo in ni fa, nel corso di oltre il 3%; il Btp decennale è'sceso «La crisi questi giorni in una conferenza di oltre il 2%. Il ministro del Tesoro Italia è di asso stampa tenuta as Dini ha parole gelide per Bankita ha cause luta gravità. La sieme . al Partito lia: il rialzo del tasso di sconto è lira perde terre S•—— popolare italiano politiche» no toccando record storici, la per illustrare la posizione del . «sgradevole», non servono misure £ d'emergenza. -

Live Music Matters Scottish Music Review

Live Music Matters Simon Frith Tovey Professor of Music, University of Edinburgh Scottish Music Review Abstract Economists and sociologists of music have long argued that the live music sector must lose out in the competition for leisure expenditure with the ever increasing variety of mediated musical goods and experiences. In the last decade, though, there is evidence that live music in the UK is one of the most buoyant parts of the music economy. In examining why this should be so this paper is divided into two parts. In the first I describe why and how live music remains an essential part of the music industry’s money making strategies. In the second I speculate about the social functions of performance by examining three examples of performance as entertainment: karaoke, tribute bands and the Pop Idol phenomenon. These are, I suggest, examples of secondary performance, which illuminate the social role of the musical performer in contemporary society. 1. The Economics of Performance Introduction It has long been an academic commonplace that the rise of mediated music (on record, radio and the film soundtrack) meant the decline of live music (in concert hall, music hall and the domestic parlour). For much of the last 50 years the UK’s live music sector, for example, has been analysed as a sector in decline. Two kinds of reason are adduced for this. On the one hand, economists, following the lead of Baumol and Bowen (1966), have assumed that live music can achieve neither the economies of scale nor the reduction of labour costs to compete with mass entertainment media. -

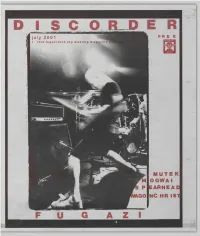

I S C O R D E R Free

I S C O R D E R FREE IUTE K OGWAI ARHEAD NC HR IS1 © "DiSCORDER" 2001 by the Student Radio Society of the University of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circuldtion 1 7,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance, to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN elsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money orders payable to DiSCORDER Mag azine. DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the August issue is July 14th. Ad space is available until July 21st and ccn be booked by calling Maren at 604.822.3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. DiS CORDER is not responsible for loss, damage, or any other injury to unsolicited mcnuscripts, unsolicit ed drtwork (including but not limited to drawings, photographs and transparencies), or any other unsolicited material. Material can be submitted on disc or in type. As always, English is preferred. Send e-mail to DSCORDER at [email protected]. From UBC to Langley and Squamish to Bellingham, CiTR can be heard at 101.9 fM as well as through all major cable systems in the Lower Mainland, except Shaw in White Rock. Call the CiTR DJ line at 822.2487, our office at 822.301 7 ext. 0, or our news and sports lines at 822.3017 ext. 2. Fax us at 822.9364, e-mail us at: [email protected], visit our web site at http://www.ams.ubc.ca/media/citr or just pick up a goddamn pen and write #233-6138 SUB Blvd., Vancouver, BC. -

Um Modelo Conceitual De Megaeventos Musicais

CULTUR, ano 09 - nº 02 – Jun/2015 www.uesc.br/revistas/culturaeturismo Licença Copyleft: Atribuição-Uso não Comercial-Vedada a Criação de Obras Derivadas UM MODELO CONCEITUAL DE MEGAEVENTOS MUSICAIS A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR MUSIC MEGA EVENTS Recebido em 13/04/2015 Fabrício Silva Barbosa1 Aprovado em 28/05/2015 1 Doutorando em Engenharia de Produção e Sistemas. Mestre em Turismo e Hotelaria. Coordenador do Curso Superior de Tecnologia em Gestão do Turismo Instituto Federal Farroupilha. RESUMO Os eventos em geral cada vez mais se encontram inseridos no cenário econômico de grandes destinações, sejam elas turísticas ou não. Por meio da implementação da produção e consumo da música, os eventos alavancam a economia local e contribuem significativamente no desenvolvimento das localidades nas quais se encontram inseridos. A presente pesquisa objetivou propor um modelo conceitual a ser utilizado no planejamento estratégico de megaeventos, analisando a sua estrutura desde a concepção, perpassando sua preparação e realização, até o encerramento total das atividades envolvidas. O resultado deste estudo aponta para a elaboração de um modelo conceitual com a finalidade de ilustrar as diferentes fases dos eventos que têm a música como facilitador da indústria do entretenimento. PALAVRAS CHAVE Gestão de Serviços. Evento. Entretenimento. Música. ABSTRACT Events are increasingly embedded in the economic scenario of large allocations, whether tourist or not. Through the implementation of production and consumption of music, events influence the local economy and contribute significantly to the development of the areas in which they are inserted. This research aimed to propose a conceptual model to be used in strategic planning for mega events, based on the supply chain of music, analyzing its structure from conception, passing their preparation and holding until the complete closure of the activities involved. -

Computational Models of Music Similarity and Their Applications In

Die approbierte Originalversion dieser Dissertation ist an der Hauptbibliothek der Technischen Universität Wien aufgestellt (http://www.ub.tuwien.ac.at). The approved original version of this thesis is available at the main library of the Vienna University of Technology (http://www.ub.tuwien.ac.at/englweb/). DISSERTATION Computational Models of Music Similarity and their Application in Music Information Retrieval ausgef¨uhrt zum Zwecke der Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der technischen Wissenschaften unter der Leitung von Univ. Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. techn. Gerhard Widmer Institut f¨urComputational Perception Johannes Kepler Universit¨atLinz eingereicht an der Technischen Universit¨at Wien Fakult¨atf¨urInformatik von Elias Pampalk Matrikelnummer: 9625173 Eglseegasse 10A, 1120 Wien Wien, M¨arz 2006 Kurzfassung Die Zielsetzung dieser Dissertation ist die Entwicklung von Methoden zur Unterst¨utzung von Anwendern beim Zugriff auf und bei der Entdeckung von Musik. Der Hauptteil besteht aus zwei Kapiteln. Kapitel 2 gibt eine Einf¨uhrung in berechenbare Modelle von Musik¨ahnlich- keit. Zudem wird die Optimierung der Kombination verschiedener Ans¨atze beschrieben und die gr¨oßte bisher publizierte Evaluierung von Musik¨ahnlich- keitsmassen pr¨asentiert. Die beste Kombination schneidet in den meisten Evaluierungskategorien signifikant besser ab als die Ausgangsmethode. Beson- dere Vorkehrungen wurden getroffen um Overfitting zu vermeiden. Um eine Gegenprobe zu den Ergebnissen der Genreklassifikation-basierten Evaluierung zu machen, wurde ein H¨ortest durchgef¨uhrt.Die Ergebnisse vom Test best¨a- tigen, dass Genre-basierte Evaluierungen angemessen sind um effizient große Parameterr¨aume zu evaluieren. Kapitel 2 endet mit Empfehlungen bez¨uglich der Verwendung von Ahnlichkeitsmaßen.¨ Kapitel 3 beschreibt drei Anwendungen von solchen Ahnlichkeitsmassen.¨ Die erste Anwendung demonstriert wie Musiksammlungen organisiert and visualisiert werden k¨onnen,so dass die Anwender den Ahnlichkeitsaspekt,¨ der sie interessiert, kontrollieren k¨onnen.