Gerri Hirshey and Anthony Bozza

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legends in Concert

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 31, 2020 CONTACT: DeAnn Lubell-Ames – (760) 831-3090 Note: Photos available at http://mccallumtheatre.com/index.php/media Legends In Concert: The Divas Tributes To Barbra Streisand, Celine Dion, Whitney Houston And Aretha Franklin McCallum Theatre Thursday – February 27 – 3:00 Pm And 8:00pm Palm Desert, CA – Through the generosity of Harold Matzner, the McCallum Theatre presents Legends in Concert—The Divas, featuring tributes to Barbra Streisand, Celine Dion, Whitney Houston and Aretha Franklin, for two shows: at 3:00pm and 8:00pm, Thursday, Feb. 27. Legends in Concert is the longest-running show in Las Vegas history, and after 35 years is still voted the No. 1 tribute show in the city. The internationally acclaimed and award-winning production is known as the pioneer of live tribute shows, and possesses the greatest collection of live tribute artists in the world. These incredible artists have pitch-perfect live vocals, signature choreography, and stunningly similar appearances to the legends they portray. Jazmine (Whitney Houston) draws her musical inspiration from her Cuban heritage while speaking and singing in both English and Spanish. After deciding to pursue her music career on the European music scene, she earned immediate success. After signing a one-album deal with Finland's K-TEL Records, Jazmine's first single achieved international success: In January 1996, "Love Like Never Before" rose to No. 1 on the French dance chart, dropping Madonna to No. 2 and passing same-week entries from Michael Jackson, Bon Jovi and Whitney Houston. She has appeared on the WB television show Pop Stars and on several episodes of the Dick Clark Productions show Your Big Break. -

Tony Winner Linda Lavin Headlines a Stellar Month of Entertainement This March at Aventura Arts & Cultural Center

February 23, 2017 Media Contact: Savannah Whaley Pierson Grant Public Relations 954/776-1999 ext. 225 Jeff Kiltie, Aventura Arts & Cultural Center 305/466-8006 TONY WINNER LINDA LAVIN HEADLINES A STELLAR MONTH OF ENTERTAINEMENT THIS MARCH AT AVENTURA ARTS & CULTURAL CENTER AVENTURA, Fla. – Tony and Golden Globe winner Linda Lavin headlines the month of March at Aventura Arts & Cultural Center, where entertainment offerings include rock and roll, nostalgic musical tributes, classical piano, electrifying illusion, dramatic film and breathtaking dance. This month begins with Presley, Perkins, Lewis & Cash on Friday, March 3 at 8 p.m., a tribute to four of music’s giants: Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis and Johnny Cash. This rock and roll royalty jam session begins with “Perkins” and “Lewis” together on stage, followed by “Cash” and “Presley” performing all the hits including “Blue Suede Shoes,” “Hound Dog,” “Great Balls of Fire” and “I Walk the Line.” Tickets are $40 and $45. Arts Ballet Theatre of Florida’s Chipollino will be staged in two shows, on Saturday, March 4 at 7 p.m. and Sunday, March 5 at 3 p.m. Choreographed by Ballet Master Vladimir Issaev to the music of Russian composer K. Katchaturian, the charming two- act ballet is based on Gianni Rodari's tale about the adventures of vegetable and fruit characters that live in the town of Limonia, centering on a naughty "green onion" by the name of Chipollino. Through music and dance, Chipollino not only tells the story of a fanciful folk tale, but also expresses a much deeper political statement. -

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Township Senior Center Adjusts, Stays Flexible During COVID

JUNE 2021 A PUBLICATION OF THE ANDERSON TOWNSHIP SENIOR CENTER Anderson Township Senior Center is back in operation and we hope to see you soon! Township Senior Center Adjusts, Stays Flexible During COVID Recovery Phase Greetings to all our members and friends! We are thrilled to While there have been so many changes this past year, our be sending you an update about the latest happenings and commitment to serve the members of our community has news at the Anderson Township Senior Center. gotten stronger. THIS HAS NOT CHANGED. As Donna Summer sang, “We will survive” and that we did! Hybrid programs will continue with Zoom experiences and The garden grew, we enjoyed the vegetables, we offered in-person events and classes. Zoom sessions and reopened our doors in November. We have issued membership cards and membership is As we reopened, ZERO required to enter. cases of COVID were linked Don’t forget as you return, to the senior center. Our lunch is served daily 11:30 a.m. team worked diligently and to 12:30 p.m. Reservations are creatively to manage all required by 10 a.m. the day operations and to engage prior. Call 474-3100 to make a members in meaningful reservation. activities as much as possible. We look forward to seeing you During this COVID recovery soon! phase, the staff encourages your return to the center. Anderson Township Senior Center 7970 Beechmont Ave. Anderson Township, OH 45255 www.andersontownship.org/senior-center June Events 2021 COVID Recovery Phase Card-making Class with Beth Music by Seldom the Same Dean, Dave & Karen Thursday, June 3 Time: 10:45 A.M. -

Book Review: the Fan Who Knew Too Much - WSJ.Com

Book Review: The Fan Who Knew Too Much - WSJ.com http://online.wsj.com/article/SB1000142405270230390150457... Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit www.djreprints.com See a sample reprint in PDF format. Order a reprint of this article now BOOKSHELF Updated June 29, 2012, 5:30 p.m. ET The Queen of Soul's Long Reign By EDDIE DEAN One of the more indelible moments from the Obama inauguration was the spectacle of Aretha Franklin singing her gospel rendition of "My Country, 'Tis of Thee," as poignant to watch as it was painful to hear. Bundled in an overcoat, gloves and a Sunday-go-to-meeting hat with a jumbo ribbon bow, she struggled in the raw winter cold to kindle her time-ravaged voice, once one of the wonders of the modern world. The performance was less about hitting the high notes than striking a chord with the flock: Here was America's Church Lady come to bless her children. It's a role that the 70-year-old Ms. Franklin plays quite well at ceremonies of state and funerals and whenever the occasion demands. But she also enjoys a Saturday night out as the reigning Queen of Soul, as when she regaled a stadium crowd at WrestleMania 23 in 2007 in her hometown of Detroit. Such cameos run the risk of making her a kind of caricature—someone who has overstayed her welcome on the pop-culture stage and become, like Orson Welles in his later years, the honorary emblem of antiquated if revered Americana. -

Deana Carter Danny Myrick

Deana Carter DEANA CARTER, the daughter of famed studio guitarist and producer Fred Carter, Jr., grew up surrounded by musical greats, including Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan, Waylon Jennings, and Simon & Garfunkel. She developed her songwriting skills at writer’s nights throughout Nashville, but her real break came when one of her demo tapes fell into the hands of Willie Nelson, who remembered Deana as a child. Impressed with how she’d grown as a songwriter, Nelson asked Deana to perform along with John Mellencamp, Kris Kristofferson, and Neil Young, as the only female solo artist to appear at Farm Aid VII in 1994. Her 1996 debut album Did I Shave My Legs for This? quickly climbed to the top of both the country and pop charts, quickly achieving multi-platinum status. "Strawberry Wine,” the first single from the album, was awarded CMA's 1997 Single of the Year. Seven albums and a decade later, Deana is still writing and producing for both the pop/rock and country markets when not on the road touring. Her superstar success continues to be evident. Her chart topper “You & Tequila,” co-written with Matraca Berg and recorded by Kenny Chesney, was nominated in 2011 as CMA’s “Song of the Year” and received two Grammy nods. Carter also recently co-wrote and produced a new album for recording artist Audra Mae while putting the finishing touches on her own Southern Way of Life that hit the shelves last December. Danny Myrick DANNY MYRICK is an award winning songwriter and musician based here in Nashville. -

Backlash Over Blair's School Revolution

Section:GDN BE PaGe:1 Edition Date:050912 Edition:01 Zone:S Sent at 11/9/2005 19:33 cYanmaGentaYellowblack Chris Patten: How the Tories lost the plot This Section Page 32 Lady Macbeth, four-letter needle- work and learning from Cate Blanchett. Judi Dench in her prime Simon Schama: G2, page 22 Amy Jenkins: America will never The me generation be the same again is now in charge G2 Page 8 G2 Page 2 £0.60 Monday 12.09.05 Published in London and Manchester guardian.co.uk Bad’day mate Aussies lose their grip Column five Backlash over The shape of things Blair’s school to come revolution Alan Rusbridger elcome to the Berliner Guardian. No, City academy plans condemned we won’t go on calling it that by ex-education secretary Morris for long, and Wyes, it’s an inel- An acceleration of plans to reform state education authorities as “commissioners egant name. education, including the speeding up of of education and champions of stan- We tried many alternatives, related the creation of the independently funded dards”, rather than direct providers. either to size or to the European origins city academy schools, will be announced The academies replace failing schools, of the format. In the end, “the Berliner” today by Tony Blair. normally on new sites, in challenging stuck. But in a short time we hope we But the increasingly controversial inner-city areas. The number of acade- can revert to being simply the Guardian. nature of the policy was highlighted when mies will rise to between 40 and 50 by Many things about today’s paper are the former education secretary Estelle next September. -

Aint Gonna Study War No More / Down by the Riverside

The Danish Peace Academy 1 Holger Terp: Aint gonna study war no more Ain't gonna study war no more By Holger Terp American gospel, workers- and peace song. Author: Text: Unknown, after 1917. Music: John J. Nolan 1902. Alternative titles: “Ain' go'n' to study war no mo'”, “Ain't gonna grieve my Lord no more”, “Ain't Gwine to Study War No More”, “Down by de Ribberside”, “Down by the River”, “Down by the Riverside”, “Going to Pull My War-Clothes” and “Study war no more” A very old spiritual that was originally known as Study War No More. It started out as a song associated with the slaves’ struggle for freedom, but after the American Civil War (1861-65) it became a very high-spirited peace song for people who were fed up with fighting.1 And the folk singer Pete Seeger notes on the record “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy and Other Love Songs”, that: "'Down by the Riverside' is, of course, one of the oldest of the Negro spirituals, coming out of the South in the years following the Civil War."2 But is the song as we know it today really as old as it is claimed without any sources? The earliest printed version of “Ain't gonna study war no more” is from 1918; while the notes to the song were published in 1902 as music to a love song by John J. Nolan.3 1 http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/grovemusic/spirituals,_hymns,_gospel_songs.htm 2 Thanks to Ulf Sandberg, Sweden, for the Pete Seeger quote. -

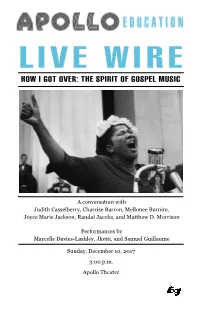

View the Program Book for How I Got Over

A conversation with Judith Casselberry, Charrise Barron, Mellonee Burnim, Joyce Marie Jackson, Randal Jacobs, and Matthew D. Morrison Performances by Marcelle Davies-Lashley, Jhetti, and Samuel Guillaume Sunday, December 10, 2017 3:00 p.m. Apollo Theater Front Cover: Mahalia Jackson; March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 1957 LIVE WIRE: HOW I GOT OVER - THE SPIRIT OF GOSPEL MUSIC In 1963, when Mahalia Jackson sang “How I Got Over” before 250,000 protesters at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, she epitomized the sound and sentiment of Black Americans one hundred years after Emancipation. To sing of looking back to see “how I got over,” while protesting racial violence and social, civic, economic, and political oppression, both celebrated victories won and allowed all to envision current struggles in the past tense. Gospel is the good news. Look how far God has brought us. Look at where God will take us. On its face, the gospel song composed by Clara Ward in 1951, spoke to personal trials and tribulations overcome by the power of Jesus Christ. Black gospel music, however, has always occupied a space between the push to individualistic Christian salvation and community liberation in the context of an unjust society— a declaration of faith by the communal “I”. From its incubation at the turn of the 20th century to its emergence as a genre in the 1930s, gospel was the sound of Black people on the move. People with purpose, vision, and a spirit of experimentation— clear on what they left behind, unsure of what lay ahead. -

Fréhel and Bessie Smith

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 9-18-2018 Fréhel and Bessie Smith: A Cross-Cultural Study of the French Realist Singer and the African American Classic Blues Singer Tiffany Renée Jackson University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Jackson, Tiffany Renée, "Fréhel and Bessie Smith: A Cross-Cultural Study of the French Realist Singer and the African American Classic Blues Singer" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1946. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1946 Fréhel and Bessie Smith: A Cross-Cultural Study of the French Realist Singer and the African American Classic Blues Singer Tiffany Renée Jackson, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 ABSTRACT In this dissertation I explore parallels between the lives and careers of the chan- son réaliste singer Fréhel (1891-1951), born Marguerite Boulc’h, and the classic blues singer Bessie Smith (1894-1937), and between the genres in which they worked. Both were tragic figures, whose struggles with love, abuse, and abandonment culminated in untimely ends that nevertheless did not overshadow their historical relevance. Drawing on literature in cultural studies and sociology that deals with feminism, race, and class, I compare the the two women’s formative environments and their subsequent biographi- cal histories, their career trajectories, the societal hierarchies from which they emerged, and, finally, their significance for developments in women’s autonomy in wider society. Chanson réaliste (realist song) was a French popular song category developed in the Parisian cabaret of the1880s and which attained its peak of wide dissemination and popularity from the 1920s through the 1940s. -

![Morgenstern, Dan. [Record Review: Earl Coleman: Love Song] Down](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6109/morgenstern-dan-record-review-earl-coleman-love-song-down-536109.webp)

Morgenstern, Dan. [Record Review: Earl Coleman: Love Song] Down

Records a re reviewed by Chris Albertson, Don DeMicheal, Gilbert M. Erskine, Ira Giller, Alan Heineman, Lawrence Kart, John Litweiler, Bill Mathieu , Marian McPartlond, Don Morgenstern, Don Nelse n, Harvey Pe kar , William Ruuo, Harvey Siders, Carol Sloane , and Pete Welding, Reviews are signed by the writers. Ratings ore: * * * * * exce llent, * * * * very good, * * * good, * * fair, * poor. When two cata log numbers ore listed, the flrst is mono, and the second is dereo . Richard Abrams ---------• comes hoa rse with excitement, and a quite accurate imitations of bird call!. LEVELS AND DEGREES OF LIGHT - Del• grace[u l manner of phrasing. He can play mark DS-4t3: Uv,is a,ut Degrees of Light; My Within this aviary there is an impassiorrd Thoughls ,sre l\fy Fu/ure-Now and Fort11er: The at a spee d about one-third slower than the duet between Braxton and Mclnlyr~. Bird Snug. basic pulse and then grad ually accelerate Personne l : Abrams. cl arinet, piano; An rhooy Extra-musica l factors make this a d.ffi. Braxton, aho saxop hon e; Maurice McIntyre, rcnor until he matches the pulse of the rhythm cult album to rate. I don't know wheille1 saxophone; Gordon Emmanuel, vibraharp (tracks section (Co ltran e does this during his My 1. 2); Leroy Jenkins, violin (crack 3 only); to blame Abrams , a&r man Bob Koe,1e: Charles Clark , bass: Leonard Jones. bass (crack Fa vorite Things solo on Coltrane L ive at the engineer, or all three, but the alb1111 3 only); Thurman Barker, drums: Penelop e Tay• the Village Vanguard Again). -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 69, 1949-1950

FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF SYMPHONY HALL BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HI SIXTY-NINTH SEASON 1949- 1950 Tuesday Evening Series BAYARD TUCKERMAN, Jr. ARTHUR J. ANDERSON ROBERT J. DUNKLE, Jr. ROBERT T. FORREST JULIUS F. HALLER ARTHUR J. ANDERSON. Jr. HERBERT SEARS TUCKERMAN OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description "A Good Reputation Does Not Just Happen It Must Be Earned." Boston, Mass. Los Angeles, California 108 Water Street 3275 Wilshire Blvd. Telephone Lafayette 3-5700 Dunkirk 8-3316 SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 6-1492 SIXTY-NINTH SEASON, 1949-1950 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra CHARLES MUNCH, Conductor Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot . President Jacob J. Kaplan . Vice-President Richard C. Paine . Treasurer Philip R. Ai len M. A. De Wolfe Howe John Nicholas Brown Charles D. Jackson Theodore P. Ferris Lewis Perry Alvan T. Fuller Edward A. Taft N. Penrose Hallowell Raymond S. Wtlkins Francis W. Hatch Oliver Wolcott George E. Judd, Manager T D. Perry, Jr. N. S. Shirk, Assistant Managers [»] Only you can decide Whether your property is large or small, it rep- resents the security for your family's future. Its ulti- mate disposition is a matter of vital concern to those you love. To assist you in considering that future, the Shaw- mut Bank has a booklet: "Should I Make a Will?" It outlines facts that everyone with property should know, and explains the many services provided by this Bank as Executor and Trustee.