RCAPS Working Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018 Laporan Tahunan 2018

Inovasi dan Digitalisasi: Menciptakan Nilai untuk Tumbuh Secara Berkelanjutan Innovation and Digitalization: Creating Value to Sustain Growth PT Astra International Tbk Laporan Tahunan 2018 Annual Report Laporan Tahunan 2018 Annual Report Innovation and Digitalization: Creating Value to Sustain Growth Amidst challenges in the economy and business throughout 2018, Astra Group maintained the sustainability of its business by continuing to build its capabilities focusing on four core areas: continuous innovation, developing globally oriented employees, being an agile organization, and being a partner of choice. Also, in the face of massive, rapid and unpredictable changes in the business landscape, Astra Group has stepped-up its digitalization initiatives to drive more effective business processes, optimize market penetration capability, and introduce various innovations and new services on digital platforms. By building digital capabilities while continuing to encourage the creation of added value for its customers, employees, business partners, shareholders and the people of Indonesia, Astra Group moves forward in its strategic journey towards the Pride of the Nation. Laporan Tahunan 2018 Annual Report ASTRA 1 Highlights Management Reports Company Profile Human Capital Management Discussion and Analysis Corporate Governance Corporate Social Responsibility Consolidated Financial Statements 2018 Inovasi dan Digitalisasi: Menciptakan Nilai untuk Tumbuh Secara Berkelanjutan Di tengah berbagai tantangan perekonomian dan bisnis sepanjang tahun -

Laporan Tahunan Annual Report KINERJA UNGGUL TAHUN 2017 KEY PERFORMANCE in 2017

Laporan Tahunan Annual Report KINERJA UNGGUL TAHUN 2017 KEY PERFORMANCE IN 2017 Laba Tahun Berjalan Pertumbuhan Aset Net Income Asset Growth mencatat kenaikan (YoY) mencatat kenaikan recorded an increase recorded an increase 12% 11% Peluncuran produk/layanan terbaru di 2017 The latest product/service launched in 2017 IMFI melakukan diversifikasi dengan meluncurkan produk pembiayaan microfinancing, yang ditopang dengan aplikasi pembiayaan "IMFI Microfinancing". IMFI diversified its business by launching microfinancing financing products, which are supported by mobile application "IMFI Microfinancing". Penghargaan Bank Indonesia 2017 Bank Indonesia Award 2017 Korporasi Pengelola Utang Luar Negeri Terbaik Best Offshore Loan Management Corporation PRAWACANA PREFACE PT Indomobil Finance Indonesia 2017 Annual Report 1 Sebagai sebuah entitas terkemuka di industri jasa pembiayaan Nasional yang telah berkiprah lebih dari 2 (dua) dekade, PT Indomobil Finance Indonesia (IMFI) senantiasa menjaga kepercayaan para stakeholders dalam menjalankan usahanya yang ditunjukkan melalui performa bisnis yang semakin baik di setiap tahunnya. Didukung oleh fundamental bisnis yang positif serta sinergi yang kuat bersama Grup Indomobil, Perseroan senantiasa menunjukkan komitmen kuat dalam menjaga reputasinya baik di mata publik maupun di mata dunia internasional. Hal tersebut terbukti dengan diperolehnya pinjaman sindikasi yang ke-7 dari beberapa institusi perbankan internasional dengan nilai sebesar USD250 juta. Guna menjamin pertumbuhan bisnis di industri jasa -

State-Owned Enterprise Governance and Privatization Program

Completion Report Project Number: 32517 Loan Number: 1866 November 2008 Indonesia: State-Owned Enterprise Governance and Privatization Program CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – rupiah (Rp) At Appraisal At Program Completion (28 February 2000) (7 October 2005) Rp1.00 = $0.000137 $0.000097 $1.00 = Rp7,305 Rp10,305 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank MOF – Ministry of Finance MSOE – Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development PPP – public-private partnership PSO – public service obligation SCI – statement of corporate intent SOE – state-owned enterprise TA – technical assistance NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government ends on 31 December. “FY” before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends. (ii) In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. Vice President C. Lawrence Greenwood, Jr., Operations Group 2 Director General A. Thapan, Southeast Asia Department (SERD) Director J. Ahmed, Governance, Finance, and Trade Division, SERD Team leader K.-P. Kriegsmann, Senior Financial Sector Specialist, SERD CONTENTS Page BASIC DATA i I. PROGRAM DESCRIPTION 1 II. EVALUATION OF DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION 2 A. Relevance of Design and Formulation 2 B. Program Outputs 3 C. Program Costs and Disbursements 10 D. Program Schedule 10 E. Implementation Arrangements 10 F. Conditions and Covenants 11 G. Related Technical Assistance 11 H. Consultant Recruitment and Procurement 12 I. Performance of Consultants, Contractors, and Suppliers 12 J. Performance of the Borrower and the Executing Agency 12 K. Performance of the Asian Development Bank 12 III. EVALUATION OF PERFORMANCE 13 A. Relevance 13 B. Effectiveness in Achieving Outcome 13 C. Efficiency in Achieving Outcome and Outputs 14 D. -

Memberdayakan Keunggulan Internal Building up Our Natural Capabilities Building up Our Natural Capabilities

Laporan Tahunan Annual Report 2017 MEMBERDAYAKAN KEUNGGULAN INTERNAL BUILDING UP OUR NATURAL CAPABILITIES BUILDING UP OUR NATURAL CAPABILITIES The year 2017 is an important milestone as Astra commemorated the 60th year anniversary since it was first established in 1957. In Astra’s six decades of journey to aspire to “Prosper with the Nation”, Astra has transformed to become an Indonesian group company with more than 210,000 employees spread across more than 200 companies throughout Indonesia. Amid the various business challenges in 2017, Astra made breakthroughs by focusing on building our natural capabilities, such as our technical and non-technical competencies, solid company culture, established management system, wide network, strong customers’ trust and high value of Astra brand. The result was Astra generated outstanding operational and business performance in 2017. With this, Astra continue its course to reach its 2020 Goal, to be “Pride of the Nation”. 1 MEMBERDAYAKAN KEUNGGULAN INTERNAL Tahun 2017 merupakan tonggak penting perjalanan Astra yang telah mencapai usia 60 tahun sejak didirikan pada tahun 1957. Dalam perjalanan enam dasawarsa Astra dalam menginspirasi negeri sekaligus mewujudkan cita-cita “Sejahtera Bersama Bangsa”, Astra telah bertransformasi menjadi satu grup perusahaan di Indonesia yang menaungi lebih dari 210.000 karyawan yang tersebar di lebih dari 200 perusahaan di seluruh tanah air. Dalam menghadapi berbagai tantangan bisnis sepanjang tahun 2017, Astra melakukan terobosan-terobosan yang memfokuskan pada pendayagunaan kapabilitas internal berupa kompetensi teknikal dan non-teknikal yang mumpuni, budaya organisasi yang kokoh, sistem manajemen yang mapan, jaringan yang luas, kepercayaan pelanggan yang kuat dan brand value Astra yang tinggi. Hasilnya, Astra meraih kinerja operasional dan bisnis yang menggembirakan di tahun 2017. -

MNCS Compendium / III / September 2018 1

MNCS Compendium / III / September 2018 1 MNCS Compendium / III / September 2018 2 MNCS Compendium / III / September 2018 Contents 04 Kata Sambutan Direktur Utama Analisis Emiten MNC Group MNC Sekuritas 06 Analisis Makroekonomi 55 PT Adaro Energy Tbk 71 MNC College Wisnu Wardana 57 PT Astra International Tbk 99 PT MNC Land Tbk 10 Investment Strategy 59 PT Bank Central Asia Tbk 61 PT Bank Tabungan Negara Tbk 13 Bond Market Update 63 PT XL Axiata Tbk Appendixes 65 PT Gudang Garam Tbk 17 SGX Indonesia Equity Futures 67 PT Indofood CBP Sukses Makmur Tbk 103 MNCS Stock Universe 69 PT Japfa Comfeed Indonesia Tbk 104 Data Obligasi 75 PT Arwana Citramulia Tbk 105 Heat Map dan Nilai Tukar Analisis Sektoral 77 PT Blue Bird Tbk 106 Kalender Ekonomi 80 PT GMF Aero Asia Tbk 21 Sektor Consumer 107 Special Thanks 83 PT Buyung Poetra Sembada Tbk 24 Sektor Telecommunication 85 PT Hartadinata Abadi Tbk 27 Sektor Metal Mining 87 PT London Sumatra Indonesia Tbk 30 Sektor Automotive 89 PT Industri Jamu dan Farmasi 35 Sektor Banking Sidomuncul Tbk 38 Sektor Coal Mining 91 PT Waskita Beton Precast Tbk 41 Sektor Plantation 44 Sektor Construction 47 Sektor Cement 50 Sektor Property 53 HARA - Empowering Billions 94 Expert Talks Session Daniel Nainggolan 73 Expert Talks Session 97 Tips & Tricks from Investment Figure 102 Learn from Millenials Adrianto Djokosoetono Sukarto Bujung LastDay Production 3 MNCS Compendium / III / September 2018 Sambutan Direktur Utama MNCS Compendium Para nasabah MNC Sekuritas yang terhormat, Tidak terasa tahun 2018 akan segera berlalu. Semangat nasionalisme terasa semakin kental setelah Indonesia sukses menjadi tuan rumah dalam kompetisi olahraga Asian Games 2018. -

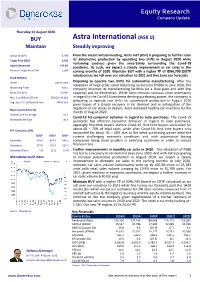

Astra International (ASII IJ) Maintain Steadily Improving

Equity Research Company Update Thursday,13 August 2020 BUY Astra International (ASII IJ) Maintain Steadily improving Last price (IDR) 5,400 From the recent virtual meeting, Astra Int’l (ASII) is preparing to further raise Target Price (IDR) 6,700 its automotive production by operating two shifts in August 2020 while remaining cautious given the uncertainty surrounding the Covid-19 Upside/Downside +24.1% pandemic. As such, we expect a steady improvement in car sales in the Previous Target Price (IDR) 5,600 coming months of 2020. Maintain BUY with a higher TP of IDR6,700 (SOTP valuation) as we roll over our valuation to 2021 and fine tune our forecasts. Stock Statistics Sector Automotive Preparing to operate two shifts for automotive manufacturing. After the relaxation of large-scale social distancing restrictions (PSBB) in June 2020, the Bloomberg Ticker ASII IJ company resumed its manufacturing facilities (at a slow pace and with low No of Shrs (mn) 40,484 capacity) and its dealerships. While Astra remains cautious amid uncertainty Mkt. Cap (IDRbn/USDmn) 218,611/14,811 in regard to the Covid-19 pandemic denting purchasing power, the company is preparing to operate two shifts for automotive production in August 2020 Avg. daily T/O (IDRbn/USDmn) 244.6/16.6 given hopes of a steady recovery in car demand and in anticipation of the Major shareholders (%) depletion of car stocks at dealers. Astra indicated healthy car inventory for the month of August 2020. Jardine Cycle & Carriage 50.1 Covid-19 hit consumer behavior in regard to auto purchases. The Covid-19 Estimated free float 49.9 pandemic has affected consumer behavior in regard to auto purchases, especially first-time buyers. -

The Material Handling Sector in South East Asia

Material Handling in South East Asia Prepared for Invest Northern Ireland July 2018 © 2018 Orissa International The Material Handling Sector Singapore | Malaysia | Indonesia | Thailand | Philippines Prepared for INVEST NORTHEN IRELAND July 2018 Orissa International Pte Ltd 1003 Bukit Merah Central #05-06 Inno Center, Singapore 159836 Tel: +65 6225 8667 | Fax: +65 6271 9791 [email protected] Disclaimer: All information contained in this publication has been researched and compiled from sources believed to be accurate and reliable at the time of publishing. Orissa International Pte Ltd accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss or damage resulting from errors, inaccuracies or omissions affecting any part of the publication. All information is provided without warranty, and Orissa International Pte Ltd makes no representation of warranty of any kind as to the accuracy or completeness of any information hereto contained. Copyright Notice: © 2018 Orissa International. All Rights Reserved. Permission to Reproduce is Required. Material Handling in South East Asia – July 2018 Table of Contents 1.0 KEY TRENDS IN THE MATERIAL HANDLING EQUIPMENT SECTOR .............................. 9 2.0 SINGAPORE .............................................................................................. 15 2.1 Singapore Country Profile ....................................................................................... 15 2.2 Overview of the Infrastructure / Building & Construction Sector .............................. 16 2.3 Overview of the -

Financial Information 1.1MB

Financial Information as of March 31, 2019 (The English translation of the “Yukashoken-Houkokusho” for the year ended March 31, 2019) Nissan Motor Co., Ltd. Table of Contents Page Cover .......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Part I Information on the Company .......................................................................................................... 2 1. Overview of the Company ......................................................................................................................... 2 1. Key financial data and trends ........................................................................................................................ 2 2. History .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Description of business ................................................................................................................................. 6 4. Information on subsidiaries and affiliates ..................................................................................................... 7 5. Employees................................................................................................................................................... 13 2. Business Overview ..................................................................................................................................... -

ASIAN AUTOMOTIVE NEWSLETTER ISSUE 16, December 1999 a Bimonthly Newsletter of Developments in the Auto and Auto Components Markets

BDA Business Development Asia ASIA IS A BUSINESS IMPERATIVE NOW MORE THAN EVER ASIAN AUTOMOTIVE NEWSLETTER ISSUE 16, December 1999 A bimonthly newsletter of developments in the auto and auto components markets CONTENTS CHINA/HK INTRODUCTION .............................................. 1 Ami Doduco, a unit of Technitrol Company of CHINA / HONG KONG ................................. 1 the US and a global leader in electrical contacts, has INDIA ..................................................................... 2 agreed to acquire Tianjin Electrical Metal Works INDONESIA ........................................................ 2 (TEM), an electrical contacts business based in JAPAN ..................................................................... 3 Tianjin, from Tianjin XinHao Investment Devel- KOREA ................................................................... 3 opment Company. Ami Doduco has established a MALAYSIA ............................................................ 4 wholly-owned enterprise in Tianjin City and obtained SINGAPORE ........................................................ 5 all approvals necessary to manufacture and sell sil- THAILAND .......................................................... 5 ver-based electrical contact products used in the ap- VIETNAM ............................................................. 5 pliance, automotive and construction industries. (No- FOCUS: Fast Fit Market in Asia ....................... 6 vember 10, 1999) Daewoo Motor Co has opened three car component JV plants -

Vanguard FTSE International Index Funds Annual

Annual Report | October 31, 2020 Vanguard FTSE International Index Funds Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US Index Fund Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US Small-Cap Index Fund See the inside front cover for important information about access to your fund’s annual and semiannual shareholder reports. Important information about access to shareholder reports Beginning on January 1, 2021, as permitted by regulations adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission, paper copies of your fund’s annual and semiannual shareholder reports will no longer be sent to you by mail, unless you specifically request them. Instead, you will be notified by mail each time a report is posted on the website and will be provided with a link to access the report. If you have already elected to receive shareholder reports electronically, you will not be affected by this change and do not need to take any action. You may elect to receive shareholder reports and other communications from the fund electronically by contacting your financial intermediary (such as a broker-dealer or bank) or, if you invest directly with the fund, by calling Vanguard at one of the phone numbers on the back cover of this report or by logging on to vanguard.com. You may elect to receive paper copies of all future shareholder reports free of charge. If you invest through a financial intermediary, you can contact the intermediary to request that you continue to receive paper copies. If you invest directly with the fund, you can call Vanguard at one of the phone numbers on the back cover of this report or log on to vanguard.com. -

RENAULT-NISSAN ALLIANCE 2004 Alliancegbguy 13/09/04 18:06 Page 2

allianceGBGuy 13/09/04 18:06 Page 1 RENAULT-NISSAN ALLIANCE 2004 allianceGBGuy 13/09/04 18:06 Page 2 CONTENTS 1 - RENAULT-NISSAN ALLIANCE BASICS 04 2 - COOPERATION IN ALL MAJOR AREAS 12 3 - THE ALLIANCE CHARTER: PRINCIPLES AND VALUES 36 4 - ALLIANCE VISION - DESTINATION 38 5-FIVE YEARS OF THE ALLIANCE 40 6 - MANAGEMENT STRUCTURES AND GOVERNANCE OF THE ALLIANCE 46 7 - OVERVIEW OF RENAULT AND NISSAN 50 8 - RENAULT AND NISSAN PRODUCT LINE-UP 52 allianceGBGuy 13/09/04 18:06 Page 4 1. RENAULT-NISSAN ALLIANCE BASICS RENAULT-NISSAN ALLIANCE THE ALLIANCE BOARD Signed on March 27, 1999, the Renault-Nissan Alliance is the first of The Alliance Board steers the Alliance’s medium- and long-term its kind involving a Japanese and a French company, each with its strategy and coordinates joint activities on a worldwide scale. own distinct corporate culture and brand identity. Both companies Renault and Nissan run their operations under their respective share a single joint strategy of profitable growth and a community of Executive Committees, accountable to their Board of Directors, and interests. To promote this shared objective, the Renault-Nissan remain individually responsible for their day-to-day management. Alliance set up joint project structures as early as June 1999 covering most of both companies’ activities. President of the Alliance Board: Louis Schweitzer Vice-President of the Alliance Board: Carlos Ghosn ALLIANCE MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE To define a common strategy and manage synergies, an Alliance strategic management company, Renault-Nissan bv*, was founded on March 28, 2002. Renault-Nissan bv is jointly and equally owned by Renault and Nissan and hosts the Alliance Board, which met for the first time on May 29, 2002, and holds monthly meetings. -

Hand-In-Hand 2008

2008 Foreword Promoting the Sound Development of the ASEAN Automotive Industry The history of steadily expanding cooperative The past several years have seen the motor ties between member companies of the Japan industries in ASEAN neighboring countries Automobile Manufacturers Association (JAMA) increasing their competitive strength, which and their ASEAN partners is now close to half a underscores the urgency of greater global century old. competitiveness for ASEAN's automotive sector. With this goal in mind, there are high hopes that Those years were marked by some difficult ASEAN will further promote regional integration times―the Asian economic crisis of 1997, for at the earliest possible time. example―but throughout, JAMA members remained firmly committed to ASEAN, ASEAN is making bold moves to surmount the consistently striving, through automobile hurdles on the path to greater growth. Such production, sales, and exports, to advance moves include the abolition of regional tariffs, investment, create jobs, and transfer technology. harmonization of automotive technical This booklet outlines the more recent activities of regulations, mutual recognition of certification, JAMA and its member companies in the ASEAN the streamlining of customs procedures and region. distribution systems, the fostering of supporting industries and human resources, the promotion In 2007, new vehicle sales in the ASEAN market of safety, greater environmental protection, and (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, other strategies aimed at promoting