Magic and Disbelief in Carolingian Lyon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sirocco Manual

SIROCCO INSTALLATION PROPER INSTALLATION IS IMPORTANT. IF YOU NEED ASSISTANCE, CONSULT A CONTRACTOR ELECTRICIAN OR TELEVISION ANTENNA INSTALLER (CHECK WITH YOUR LOCAL BUILDING SUPPLY, OR HARDWARE STORE FOR REFERRALS). TO PROMOTE CONFIDENCE, PERFORM A TRIAL WIRING BEFORE INSTALLATION. Determine where you are going to locate both the 1 rooftop sensor and the read-out. Feed the terminal lug end of the 2-conductor cable through 2 2-CONDUCTOR WIND SPEED the rubber boot and connect the lugs to the terminals on the bottom CABLE SENSOR of the wind speed sensor. (Do NOT adjust the nuts that are already BOOT on the sensor). The polarity does not matter. COTTER PIN 3 Slide the stub mast through the rubber boot and insert the stub mast into the bottom of the wind speed sensor. Secure with the cotter pin. Coat all conections with silicone sealant and slip the boot over the sensor. STRAIGHT STUB MAST Secure the sensor and the stub mast to your antenna 2-CONDUCTOR mast (not supplied) with the two hose clamps. Radio CABLE 4 Shack and similar stores have a selection of antenna HOSE CLAMPS masts and roof mounting brackets. Choose a mount that best suits your location and provides at least eight feet of vertical clearance above objects on the roof. TALL MAST EVE 8 FEET 5 Follow the instructions supplied with the antenna MOUNT VENT-PIPE mount and secure the mast to the mount. MOUNT CABLE WALL CHIMNEY Secure the wire to the building using CLIPS TRIPOD MOUNT MOUNT MOUNT 6 CAULK cable clips (do not use regular staples). -

Tornado Safety Q & A

TORNADO SAFETY Q & A The Prosper Fire Department Office of Emergency Management’s highest priority is ensuring the safety of all Prosper residents during a state of emergency. A tornado is one of the most violent storms that can rip through an area, striking quickly with little to no warning at all. Because the aftermath of a tornado can be devastating, preparing ahead of time is the best way to ensure you and your family’s safety. Please read the following questions about tornado safety, answered by Prosper Emergency Management Coordinator Kent Bauer. Q: During s evere weather, what does the Prosper Fire Department do? A: We monitor the weather alerts sent out by the National Weather Service. Because we are not meteorologists, we do not interpret any sort of storms or any sort of warnings. Instead, we pass along the information we receive from the National Weather Service to our residents through social media, storm sirens and Smart911 Rave weather warnings. Q: What does a Tornado Watch mean? A: Tornadoes are possible. Remain alert for approaching storms. Watch the sky and stay tuned to NOAA Weather Radio, commercial radio or television for information. Q: What does a Tornado Warning mean? A: A tornado has been sighted or indicated by weather radar and you need to take shelter immediately. Q: What is the reason for setting off the Outdoor Storm Sirens? A: To alert those who are outdoors that there is a tornado or another major storm event headed Prosper’s way, so seek shelter immediately. I f you are outside and you hear the sirens go off, do not call 9-1-1 to ask questions about the warning. -

Imagine2014 8B3 02 Gehrke

Loss Adjustment via Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) – Experiences and Challenges for Crop Insurance Thomas Gehrke, Regional Director Berlin, Resp. for International Affairs Loss Adjustment via UAS - Experiences and 20.10.2014 1 Challenges for Crop Insurance Structure 1. Introduction – Demo 2. Vereinigte Hagel – Market leader in Europe 3. Precision Agriculture – UAS 4. Crop insurance – Loss adjustment via UAS 5. Challenges and Conclusion Loss Adjustment via UAS - Experiences and Challenges for Crop Insurance 20.10.2014 2 Introduction – Demo Short film (not in pdf-file) Loss Adjustment via UAS - Experiences and Challenges for Crop Insurance 20.10.2014 3 Structure 1. Introduction – Demo 2. Vereinigte Hagel – Market leader in Europe 3. Precision Agriculture – UAS 4. Crop insurance – Loss adjustment via UAS 5. Challenges and Conclusion Loss Adjustment via UAS - Experiences and Challenges for Crop Insurance 20.10.2014 4 190 years of experience Secufarm® 1 Hail * Loss Adjustment via UAS - Experiences and Challenges for Crop Insurance 20.10.2014 5 2013-05-09, Hail – winter barley Loss Adjustment via UAS - Experiences and Challenges for Crop Insurance 20.10.2014 6 … and 4 weeks later Loss Adjustment via UAS - Experiences and Challenges for Crop Insurance 20.10.2014 7 Our Line of MPCI* Products PROFESSIONAL RISK MANAGEMENT is crucial part of modern agriculture. With Secufarm® products, farmers can decide individually which agricultural Secufarm® 6 crops they would like to insure against ® Fire & Drought which risks. Secufarm 4 Frost Secufarm® 3 Storm & Intense Rain Secufarm® 1 certain crop types are eligible Hail only for Secufarm 1 * MPCI: Multi Peril Crop Insurance Loss Adjustment via UAS - Experiences and Challenges for Crop Insurance 20.10.2014 8 Insurable Damages and their Causes Hail Storm Frost WEATHER RISKS are increasing further. -

PROTECT YOUR PROPERTY from STORM SURGE Owning a House Is One of the Most Important Investments Most People Make

PROTECT YOUR PROPERTY FROM STORM SURGE Owning a house is one of the most important investments most people make. Rent is a large expense for many households. We work hard to provide a home and a future for ourselves and our loved ones. If you live near the coast, where storm surge is possible, take the time to protect yourself, your family and your belongings. Storm surge is the most dangerous and destructive part of coastal flooding. It can turn a peaceful waterfront into a rushing wall of water that floods homes, erodes beaches and damages roadways. While you can’t prevent a storm surge, you can minimize damage to keep your home and those who live there safe. First, determine the Base Flood Elevation (BFE) for your home. The BFE is how high floodwater is likely to rise during a 1%-annual-chance event. BFEs are used to manage floodplains in your community. The regulations about BFEs could affect your home. To find your BFE, you can look up your address on the National Flood Hazard Layer. If you need help accessing or understanding your BFE, contact FEMA’s Flood Mapping and Insurance eXchange. You can send an email to FEMA-FMIX@ fema.dhs.gov or call 877 FEMA MAP (877-336-2627). Your local floodplain manager can help you find this information. Here’s how you can help protect your home from a storm surge. OUTSIDE YOUR HOME ELEVATE While it is an investment, elevating your SECURE Do you have a manufactured home and want flood insurance YOUR HOME home is one of the most effective ways MANUFACTURED from the National Flood Insurance Program? If so, your home to mitigate storm surge effects. -

February 2021 Historical Winter Storm Event South-Central Texas

Austin/San Antonio Weather Forecast Office WEATHER EVENT SUMMARY February 2021 Historical Winter Storm Event South-Central Texas 10-18 February 2021 A Snow-Covered Texas. GeoColor satellite image from the morning of 15 February, 2021. February 2021 South Central Texas Historical Winter Storm Event South-Central Texas Winter Storm Event February 10-18, 2021 Event Summary Overview An unprecedented and historical eight-day period of winter weather occurred between 10 February and 18 February across South-Central Texas. The first push of arctic air arrived in the area on 10 February, with the cold air dropping temperatures into the 20s and 30s across most of the area. The first of several frozen precipitation events occurred on the morning of 11 February where up to 0.75 inches of freezing rain accumulated on surfaces in Llano and Burnet Counties and 0.25-0.50 inches of freezing rain accumulated across the Austin metropolitan area with lesser amounts in portions of the Hill Country and New Braunfels area. For several days, the cold air mass remained in place across South-Central Texas, but a much colder air mass remained stationary across the Northern Plains. This record-breaking arctic air was able to finally move south into the region late on 14 February and into 15 February as a strong upper level low-pressure system moved through the Southern Plains. As this system moved through the region, snow began to fall and temperatures quickly fell into the single digits and teens. Most areas of South-Central Texas picked up at least an inch of snow with the highest amounts seen from Del Rio and Eagle Pass extending to the northeast into the Austin and San Antonio areas. -

Agobard of Lyon, Empire, and Adoptionism Reusing Heresy to Purify the Faith

Agobard of Lyon, Empire, and Adoptionism Reusing Heresy to Purify the Faith Rutger Kramer Institute for Medieval Research, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, Austria ABSTRACT — In the late eighth century, the heterodox movement Adoptionism emerged at the edge of the Carolingian realm. Initially, members of the Carolingian court considered it a threat to the ecclesiastical reforms they were spearheading, but they also used the debate against Adoptionism as an opportunity to extend their influence south of the Pyrenees. While they thought the movement had been eradicated around the turn of the ninth century, Archbishop Agobard of Lyon claimed to have found a remnant of this heresy in his diocese several decades later, and decided to alert the imperial court. This article explains some of his motives, and, in the process, reflects on how these early medieval rule-breakers (real or imagined) could be used in various ways by those making the rules: to maintain the purity of Christendom, to enhance the authority of the Empire, or simply to boost one’s career at the Carolingian court. 1 Alan H. Goldman, “Rules and INTRODUCTION Moral Reasoning,” Synthese 117 (1998/1999), 229-50; Jim If some rules are meant to be broken, others are only formulated once their Leitzel, The Political Economy of Rule Evasion and Policy Reform existence satisfies a hitherto unrealized need. Unspoken rules are codified – and (London: Routledge, 2003), 8-23. thereby become institutions – once they have been stretched to their breaking 8 | journal of the lucas graduate conference rutger Kramer point and their existence is considered morally right or advantageous to those in a 2 Alan Segal, “Portnoy’s position to impose them.1 Conversely, the idea that rules can be broken at all rests Complaint and the Sociology of Literature,” The British Journal on the assumption that they reflect some kind of common interest; if unwanted of Sociology 22 (1971), 257-68; rules are simply imposed on a group by an authority, conflict may ensue and be see also Warren C. -

Climatic Information of Western Sahel F

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Clim. Past Discuss., 10, 3877–3900, 2014 www.clim-past-discuss.net/10/3877/2014/ doi:10.5194/cpd-10-3877-2014 CPD © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 10, 3877–3900, 2014 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Climate of the Past (CP). Climatic information Please refer to the corresponding final paper in CP if available. of Western Sahel V. Millán and Climatic information of Western Sahel F. S. Rodrigo (1535–1793 AD) in original documentary sources Title Page Abstract Introduction V. Millán and F. S. Rodrigo Conclusions References Department of Applied Physics, University of Almería, Carretera de San Urbano, s/n, 04120, Almería, Spain Tables Figures Received: 11 September 2014 – Accepted: 12 September 2014 – Published: 26 September J I 2014 Correspondence to: F. S. Rodrigo ([email protected]) J I Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Back Close Full Screen / Esc Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 3877 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract CPD The Sahel is the semi-arid transition zone between arid Sahara and humid tropical Africa, extending approximately 10–20◦ N from Mauritania in the West to Sudan in the 10, 3877–3900, 2014 East. The African continent, one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change, 5 is subject to frequent droughts and famine. One climate challenge research is to iso- Climatic information late those aspects of climate variability that are natural from those that are related of Western Sahel to human influences. -

Severe Thunderstorms and Tornadoes Toolkit

SEVERE THUNDERSTORMS AND TORNADOES TOOLKIT A planning guide for public health and emergency response professionals WISCONSIN CLIMATE AND HEALTH PROGRAM Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health dhs.wisconsin.gov/climate | SEPTEMBER 2016 | [email protected] State of Wisconsin | Department of Health Services | Division of Public Health | P-01037 (Rev. 09/2016) 1 CONTENTS Introduction Definitions Guides Guide 1: Tornado Categories Guide 2: Recognizing Tornadoes Guide 3: Planning for Severe Storms Guide 4: Staying Safe in a Tornado Guide 5: Staying Safe in a Thunderstorm Guide 6: Lightning Safety Guide 7: After a Severe Storm or Tornado Guide 8: Straight-Line Winds Safety Guide 9: Talking Points Guide 10: Message Maps Appendices Appendix A: References Appendix B: Additional Resources ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Wisconsin Severe Thunderstorms and Tornadoes Toolkit was made possible through funding from cooperative agreement 5UE1/EH001043-02 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the commitment of many individuals at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS), Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health (BEOH), who contributed their valuable time and knowledge to its development. Special thanks to: Jeffrey Phillips, RS, Director of the Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health, DHS Megan Christenson, MS,MPH, Epidemiologist, DHS Stephanie Krueger, Public Health Associate, CDC/ DHS Margaret Thelen, BRACE LTE Angelina Hansen, BRACE LTE For more information, please contact: Colleen Moran, MS, MPH Climate and Health Program Manager Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health 1 W. Wilson St., Room 150 Madison, WI 53703 [email protected] 608-266-6761 2 INTRODUCTION Purpose The purpose of the Wisconsin Severe Thunderstorms and Tornadoes Toolkit is to provide information to local governments, health departments, and citizens in Wisconsin about preparing for and responding to severe storm events, including tornadoes. -

The Heirs of Alcuin: Education and Clerical Advancement in Ninth-Century Carolingian Europe

The Heirs of Alcuin: Education and Clerical Advancement in Ninth-Century Carolingian Europe Darren Elliot Barber Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Institute for Medieval Studies December 2019 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. iii Acknowledgements I wish to thank my supervisors, Julia Barrow and William Flynn, for their sincere encouragement and dedication to this project. Heeding their advice early on made this research even more focused, interesting, and enjoyable than I had hoped it would be. The faculty and staff of the Institute for Medieval Studies and the Brotherton Library have been very supportive, and I am grateful to Melanie Brunner and Jonathan Jarrett for their good advice during my semesters of teaching while writing this thesis. I also wish to thank the Reading Room staff of the British Library at Boston Spa for their friendly and professional service. Finally, I would like to thank Jonathan Jarrett and Charles West for conducting such a gracious viva examination for the thesis, and Professor Stephen Alford for kindly hosting the examination. iv Abstract During the Carolingian renewal, Alcuin of York (c. 740–804) played a major role in promoting education for children who would later join the clergy, and encouraging advanced learning among mature clerics. -

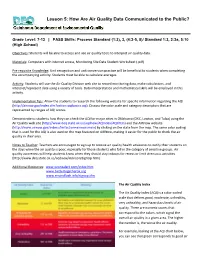

Lesson 5: How Are Air Quality Data Communicated to the Public?

Lesson 5: How Are Air Quality Data Communicated to the Public? Grade Level: 7-12 | PASS Skills: Process Standard (1:3), 3, (4:2-5, 8)/ Standard 1:3, 2:2a, 5:10 (High School) Objectives: Students will be able to access and use air quality tools to interpret air quality data. Materials: Computers with internet access, Monitoring Site Data Student Worksheet (.pdf) Pre‐requisite Knowledge: Unit recognition and unit conversion practice will be beneficial to students when completing the accompanying activity. Students must be able to calculate averages. Activity: Students will use the Air Quality Division web site to record monitoring data, make calculations, and interpret/represent data using a variety of tools. Data interpretation and mathematical skills will be employed in this activity. Implementation Tips: Allow the students to research the following website for specific information regarding the AQI (http://airnow.gov/index.cfm?action=aqibasics.aqi). Discuss the color scale and category descriptors that are represented by ranges of AQI scores. Demonstrate to students how they can check the AQI for major cities in Oklahoma (OKC, Lawton, and Tulsa) using the Air Quality web site (http://www.deq.state.ok.us/aqdnew/AQIndex/AQI.htm) and the AIRNow website (http://www.airnow.gov/index.cfm?action=airnow.main) by clicking on the state from the map. The same color coding that is used for the AQI is also used on the map featured on AIRNow, making it easier for the public to check the air quality in their area. Notes to Teacher: Teachers are encouraged to sign up to receive air quality health advisories to notify their students on the days when the air quality is poor, especially for those students who fall in the category of sensitive groups. -

North American Notes

268 NORTH AMERICAN NOTES NORTH AMERICAN NOTES BY KENNETH A. HENDERSON HE year I 967 marked the Centennial celebration of the purchase of Alaska from Russia by the United States and the Centenary of the Articles of Confederation which formed the Canadian provinces into the Dominion of Canada. Thus both Alaska and Canada were in a mood to celebrate, and a part of this celebration was expressed · in an extremely active climbing season both in Alaska and the Yukon, where some of the highest mountains on the continent are located. While much of the officially sponsored mountaineering activity was concentrated in the border mountains between Alaska and the Yukon, there was intense activity all over Alaska as well. More information is now available on the first winter ascent of Mount McKinley mentioned in A.J. 72. 329. The team of eight was inter national in scope, a Frenchman, Swiss, German, Japanese, and New Zealander, the rest Americans. The successful group of three reached the summit on February 28 in typical Alaskan weather, -62° F. and winds of 35-40 knots. On their return they were stormbound at Denali Pass camp, I7,3oo ft. for seven days. For the forty days they were on the mountain temperatures averaged -35° to -40° F. (A.A.J. I6. 2I.) One of the most important attacks on McKinley in the summer of I967 was probably the three-pronged assault on the South face by the three parties under the general direction of Boyd Everett (A.A.J. I6. IO). The fourteen men flew in to the South east fork of the Kahiltna glacier on June 22 and split into three groups for the climbs. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere.