Guru Nanak. at Another Place He Refers to the Sadhan-I-Nanak Shahl, Without Indicating Whether They Were Ramdasi Or Udasl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Mesolithic Site in the Thal Desert of Punjab (Pakistan)

Asian Archaeology https://doi.org/10.1007/s41826-019-00024-z FIELD WORK REPORT Mahi Wala 1 (MW-1): a Mesolithic site in the Thal desert of Punjab (Pakistan) Paolo Biagi 1 & Elisabetta Starnini2 & Zubair Shafi Ghauri3 Received: 4 April 2019 /Accepted: 12 June 2019 # Research Center for Chinese Frontier Archaeology (RCCFA), Jilin University and Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2019 1Preface considered by a few authors a transitional period that covers ca two thousand years between the end of the Upper The problem of the Early Holocene Mesolithic hunter-gatherers Palaeolithic and the beginning of the Neolithic food producing in the Indian Subcontinent is still a much debated topic in the economy (Misra 2002: 112). The reasons why our knowledge prehistory of south Asia (Lukacs et al. 1996; Sosnowska 2010). of the Mesolithic period in the Subcontinent in general is still Their presence often relies on knapped stone assemblages insufficiently known is due mainly to 1) the absence of a de- characterised by different types of geometric microlithic arma- tailed radiocarbon chronology to frame the Mesolithic com- tures1 (Kajiwara 2008: 209), namely lunates, triangles and tra- plexes into each of the three climatic periods that developed pezes, often obtained with the microburin technique (Tixier at the beginning of the Holocene and define a correct time-scale et al. 1980; Inizan et al. 1992; Nuzhniy 2000). These tools were for the development or sequence of the study period in the area first recorded from India already around the end of the (Misra 2013: 181–182), 2) the terminology employed to de- nineteenth century (Carleyle 1883; Black 1892; Smith scribe the Mesolithic artefacts that greatly varies author by au- 1906), and were generically attributed to the beginning thor (Jayaswal 2002), 3) the inhomogeneous criteria adopted of the Holocene some fifty years later (see f.i. -

Caste, Trade Or Class: Historical Transition in Stratification Structure in Rural Punjab

Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society Volume: 34, No. 01, January – June 2021 Ayesha Farooq * Caste, Trade or Class: Historical Transition in Stratification Structure in Rural Punjab Abstract Dynamics of caste have modified over time due to occupational changes, economic positions and religious enlightenment. However, it is not entirely replaced by any new stratification structure, resulting in much confusion regarding the adopted caste titles in the community. The present research has been conducted in a village named Mohla in the Punjab, Pakistan. Findings revealed resistance of young generation towards the existing caste system and they were recognized by trades of their forefather. Economic factor found important for such differences, besides education and migration. There has been fluidity of caste perception over generation and across social strata; young, educated, economically better off craftsmen and women condemned caste division whereas most of the landowners emphasized the importance of caste system. Shift in basis of social differentiation, role of chieftain has become negligible as majority of them tend to resolve their issues by themselves and go to police or courts. Keywords: Caste system, Class structure, social stratification, intergenerational differences, economics, migration, infrastructure. Introduction The present paper aims to assess stratification system in a rural community named Mohla, situated in District Gujrat of Punjab, Pakistan. Implications of caste on various aspects of social life are also observed. Eglar studied this village five decades ago and found caste stratification as foremost aspect in determining social status and life opportunities.1 In this study, we intend to look into the differences between old and young villager’s perception regarding caste system. -

Know Your Heritage Introductory Essays on Primary Sources of Sikhism

KNOW YOUR HERIGAGE INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS ON PRIMARY SOURCES OF SIKHISM INSTITUTE OF S IKH S TUDIES , C HANDIGARH KNOW YOUR HERITAGE INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS ON PRIMARY SOURCES OF SIKHISM Dr Dharam Singh Prof Kulwant Singh INSTITUTE OF S IKH S TUDIES CHANDIGARH Know Your Heritage – Introductory Essays on Primary Sikh Sources by Prof Dharam Singh & Prof Kulwant Singh ISBN: 81-85815-39-9 All rights are reserved First Edition: 2017 Copies: 1100 Price: Rs. 400/- Published by Institute of Sikh Studies Gurdwara Singh Sabha, Kanthala, Indl Area Phase II Chandigarh -160 002 (India). Printed at Adarsh Publication, Sector 92, Mohali Contents Foreword – Dr Kirpal Singh 7 Introduction 9 Sri Guru Granth Sahib – Dr Dharam Singh 33 Vars and Kabit Swiyyas of Bhai Gurdas – Prof Kulwant Singh 72 Janamsakhis Literature – Prof Kulwant Singh 109 Sri Gur Sobha – Prof Kulwant Singh 138 Gurbilas Literature – Dr Dharam Singh 173 Bansavalinama Dasan Patshahian Ka – Dr Dharam Singh 209 Mehma Prakash – Dr Dharam Singh 233 Sri Gur Panth Parkash – Prof Kulwant Singh 257 Sri Gur Partap Suraj Granth – Prof Kulwant Singh 288 Rehatnamas – Dr Dharam Singh 305 Know your Heritage 6 Know your Heritage FOREWORD Despite the widespread sweep of globalization making the entire world a global village, its different constituent countries and nations continue to retain, follow and promote their respective religious, cultural and civilizational heritage. Each one of them endeavours to preserve their distinctive identity and take pains to imbibe and inculcate its religio- cultural attributes in their younger generations, so that they continue to remain firmly attached to their roots even while assimilating the modern technology’s influence and peripheral lifestyle mannerisms of the new age. -

Neighboring Risk BOOK

Neighboring Risk An Alternative Approach to Understanding and Responding to Hazards and Vulnerability in Pakistan Neighboring Risk: An Alternative Approach to Understanding and Responding to Hazards and Vulnerability in Pakistan Published by: Rural Development Policy Institute (RDPI), Islamabad Copyright © 2010 Rural Development Policy Institute Office 6, Ramzan Plaza, G 9 Markaz, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: +92 51 285 6623, +92 51 285 4523 Fax: +92 51 285 4783 URL: www.rdpi.org.pk This publication is produced by RDPI with financial support from Plan Pakistan. Citation is encouraged. Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non- commercial purpose is authorized without prior written permission from RDPI, provided the source is fully acknowledged.Production, resale or other commercial purposes are prohibited without prior written permission from RDPI, Islamabad, Pakistan. Citation: RDPI, Neighboring Risk, Islamabad, 2010 Authored by: Abdul Shakoor Sindhu Research Team: Beenish Kulsoom, Saqib Shehzad, Tariq Chishti, Tailal Masood, Gulzar Habib, Abida Nasren, Qaswer Abbas Text Editing: Masood Alam Cover & Layout Design: Abdul Shakoor Sindhu Photos: Abdul Shakoor Sindhu, Saqib Shehzad, Beenish Kulsoom, Tariq Chishti, Asif Khattak Printed by: Khursheed Printers, 15-Khayaban-e-Suhrawardy, Aabpara, Islamabad. Ph: 051-2277399 Available from: Rural Development Policy Institute Office 6, Ramzan Plaza, G-9 Markaz, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: +92 51 285 6623, +92 51 285 4523 Fax: +92 51 285 4783 Website: www.rdpi.org.pk Be a part of it Rural Development Policy Institute (RDPI) is a civil 'Plan' is an international organization working in initiative aimed to stimulate public dialogue on policies, Pakistan since 1997. Plan's activities focus on safe inform public action, and activate social regrouping to motherhood and child survival, children's access to celebrate capacities and address vulnerabilities of quality education, water and sanitation, community resource-poor rural communities in Pakistan. -

The Titles of the Naqshbandi Golden Chain

For more books visit Facebook Group ‘SUFI LITERATURE’ or Click on the link https://m.facebook.com/groups/14641 63117130957 PDF made by ZAHID HUSSAIN DAR Email: [email protected] The Titles of the Naqshbandi Golden Chain The designation of the Naqshbandi Golden Chain has changed from century to century. From the time of Abu Bakr as-Siddiq (r) to the time of Bayazid al- Bistami (r) it was called as-Siddiqiyya. From the time of Bayazid to the time of Sayyidina Abdul Khaliq al-Ghujdawani it was called at-Tayfuriyya. From the time of Sayyidina ‘Abdul Khaliq al-Ghujdawan to the time of Shah Naqshband it was called the Khwajaganiyya. From the time of Shah Naqshband through the time of Sayyidina Ubaidullah al-Ahrar and Sayyidina Ahmad Faruqi, it was called Naqshbandiyya. Naqshbandiyya means to “tie the Naqsh very well.” The Naqsh is the perfect engraving of Allah’s Name in the heart of the murid. From the time of Sayyidina Ahmad al-Faruqi to the time of Shaikh Khalid al-Baghdadi it was called Naqshbandi-Mujaddidiyya. From the time of Sayyidina Khalid al- Baghdadi until the time of Sayiddina Shaikh Ismail Shirwani it was called the Naqshbandiyya-Khalidiyya. From the time of Sayyidina Isma’il Shirwani until the time of Sayyidina Shaikh ‘Abdullah ad-Daghestani, it was called Naqshbandi-Daghestaniyya. And today it is known by the name Naqshbandiyya-Haqqaniyya. The Chain Chapters: The Naqshbandi Sufi Way: History and Guidebook of the Saints of the Golden Chain© by Shaykh Muhammad Hisham Kabbani Prophet Muhammad ibn Abd Allah Abu Bakr as-Siddiq, -

Administrative Atlas , Punjab

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 PUNJAB ADMINISTRATIVE ATLAS f~.·~'\"'~ " ~ ..... ~ ~ - +, ~... 1/, 0\ \ ~ PE OPLE ORIENTED DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, PUNJAB , The maps included in this publication are based upon SUNey of India map with the permission of the SUNeyor General of India. The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of twelve nautical miles measured from the appropriate base line. The interstate boundaries between Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Meghalaya shown in this publication are as interpreted from the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971 but have yet to be verified. The state boundaries between Uttaranchal & Uttar Pradesh, Bihar & Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh & Madhya Pradesh have not been verified by government concerned. © Government of India, Copyright 2006. Data Product Number 03-010-2001 - Cen-Atlas (ii) FOREWORD "Few people realize, much less appreciate, that apart from Survey of India and Geological Survey, the Census of India has been perhaps the largest single producer of maps of the Indian sub-continent" - this is an observation made by Dr. Ashok Mitra, an illustrious Census Commissioner of India in 1961. The statement sums up the contribution of Census Organisation which has been working in the field of mapping in the country. The Census Commissionarate of India has been working in the field of cartography and mapping since 1872. A major shift was witnessed during Census 1961 when the office had got a permanent footing. For the first time, the census maps were published in the form of 'Census Atlases' in the decade 1961-71. Alongwith the national volume, atlases of states and union territories were also published. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN 98, MAULANA AZAD AND Andaman & ROAD, PORT BLAIR, NICOBAR Nicobar State 744101, ANDAMAN & 943428146 ISLAND ANDAMAN Coop Bank Ltd NICOBAR ISLAND PORT BLAIR HDFC0CANSCB 0 - 744656002 HDFC BANK LTD. 201, MAHATMA ANDAMAN GANDHI ROAD, AND JUNGLIGHAT, PORT NICOBAR BLAIR ANDAMAN & 98153 ISLAND ANDAMAN PORT BLAIR NICOBAR 744103 PORT BLAIR HDFC0001994 31111 ANDHRA HDFC BANK LTD6-2- 022- PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD 57,CINEMA ROAD ADILABAD HDFC0001621 61606161 SURVEY NO.109 5 PLOT NO. 506 28-3- 100 BELLAMPALLI ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH BELLAMPAL 99359 PRADESH ADILABAD BELLAMPALLI 504251 LI HDFC0002603 03333 NO. 6-108/5, OPP. VAGHESHWARA JUNIOR COLLEGE, BEAT BAZAR, ANDHRA LAXITTIPET ANDHRA LAKSHATHI 99494 PRADESH ADILABAD LAXITTIPET PRADESH 504215 PET HDFC0003036 93333 - 504240242 18-6-49, AMBEDKAR CHOWK, MUKHARAM PLAZA, NH-16, CHENNUR ROAD, MANCHERIAL - MANCHERIAL ANDHRA ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH MANCHERIY 98982 PRADESH ADILABAD PRADESH 504208 AL HDFC0000743 71111 NO.1-2-69/2, NH-7, OPPOSITE NIRMAL ANDHRA BUS DEPO, NIRMAL 98153 PRADESH ADILABAD NIRMAL PIN 504106 NIRMAL HDFC0002044 31111 #5-495,496,Gayatri Towers,Iqbal Ahmmad Ngr,New MRO Office- THE GAYATRI Opp ANDHRA CO-OP URBAN Strt,Vill&Mdl:Mancheri MANCHERIY 924894522 PRADESH ADILABAD BANK LTD al:Adilabad.A.P AL HDFC0CTGB05 2 - 504846202 ANDHRA Universal Coop Vysya Bank Road, MANCHERIY 738203026 PRADESH ADILABAD Urban Bank Ltd Mancherial-504208 AL HDFC0CUCUB9 1 - 504813202 11-129, SREE BALAJI ANANTHAPUR - RESIDENCY,SUBHAS -

Judicial System in India During Mughal Period with Special Reference to Persian Sources

Judicial System in India during Mughal Period with Special Reference to Persian Sources (Nezam-e-dadgahi-e-Hend der ahd-e-Gorkanian bewizha-e manabe-e farsi) For the Award ofthe Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submitted by Md. Sadique Hussain Under the Supervision of Dr. Akhlaque Ahmad Ansari Center Qf Persian and Central Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi -110067. 2009 Center of Persian and Central Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi -110067. Declaration Dated: 24th August, 2009 I declare that the work done in this thesis entitled "Judicial System in India during Mughal Period with special reference to Persian sources", for the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy, submitted by me is an original research work and has not been previously submitted for any other university\Institution. Md.Sadique Hussain (Name of the Scholar) Dr.Akhlaque Ahmad Ansari (Supervisor) ~1 C"" ~... ". ~- : u- ...... ~· c "" ~·~·.:. Profess/~ar Mahdi 4 r:< ... ~::.. •• ~ ~ ~ :·f3{"~ (Chairperson) L~.·.~ . '" · \..:'lL•::;r,;:l'/ [' ft. ~ :;r ':1 ' . ; • " - .-.J / ~ ·. ; • : f • • ~-: I .:~ • ,. '· Attributed To My Parents INDEX Acknowledgment Introduction 1-7 Chapter-I 8-60 Chapter-2 61-88 Chapter-3 89-131 Chapter-4 132-157 Chapter-S 158-167 Chapter-6 168-267 Chapter-? 268-284 Chapter-& 285-287 Chapter-9 288-304 Chapter-10 305-308 Conclusion 309-314 Bibliography 315-320 Appendix 321-332 Acknowledgement At first I would like to praise God Almighty for making the tough situations and conditions easy and favorable to me and thus enabling me to write and complete my Ph.D Thesis work. -

Pincode Officename Statename Minisectt Ropar S.O Thermal Plant

pincode officename districtname statename 140001 Minisectt Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Thermal Plant Colony Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Ropar H.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Morinda S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140101 Bhamnara B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Rattangarh Ii B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Saheri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Dhangrali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Tajpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Lutheri S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Rollumajra B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Kainaur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Makrauna Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Samana Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Barsalpur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Chaklan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Dumna B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140103 Kurali S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Allahpur B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Burmajra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Chintgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Dhanauri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Jhingran Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Kalewal B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Kaishanpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Mundhon Kalan B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sihon Majra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Singhpura B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sotal B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Sahauran B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140108 Mian Pur S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Pathreri Jattan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Rangilpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Sainfalpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Singh Bhagwantpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Kotla Nihang B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140108 Behrampur Zimidari B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Ballamgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Purkhali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140109 Khizrabad West S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140109 Kubaheri B.O Mohali PUNJAB -

The Dayanand Anglo-Vedic School of Lahore: a Study of Educational Reform in Colonial Punjab, Ca

The Dayanand Anglo-Vedic School of Lahore: A Study of Educational Reform in Colonial Punjab, ca. 1885-1925. Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Heidelberg vorgelegt von: Ankur Kakkar Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Gita Dharampal-Frick Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Rahul Mukherji Heidelberg, April 2021 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... 5 LIST OF MAPS AND TABLES ................................................................................................. 8 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 11 CHAPTER 1: EDUCATION POLICY IN COLONIAL INDIA. A HISTORICAL BACKGROUND, CA. 1800-1880 ........................................................................................................................ 33 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 33 ‘INDIGENOUS’ INDIAN EDUCATION : A COLONIAL SURVEY, CA. 1820-1830 ......................................... 34 Madras ........................................................................................................................... 38 Bombay .......................................................................................................................... 42 Bengal ........................................................................................................................... -

Branches of Ubl to Collect Board's Dues

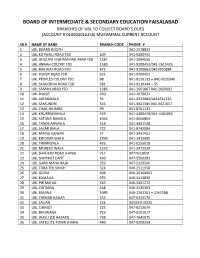

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE & SECONDARY EDUCATION FAISALABAD BRANCHES OF UBL TO COLLECT BOARD’S DUES (ACCOUNT # 010901016256) MUKAMMAL CURRENT ACCOUNT SR.# NAME OF BANK BRANCH CODE PHONE. # 1 UBL BOARD BOOTH - 041-2578833 2 UBL KOTWALI ROAD FSD 109 041-9200453 3 UBL GHULAM MUHAMMAD ABAD FSD 1287 041-2694655 4 UBL JINNAH COLONY FSD 1580 041-9200452/041-2615425 5 UBL RAILWAY ROAD FSD 472 041-9200662/0419200884 6 UBL DIJKOT ROAD FSD 531 041-9200451 7 UBL PEOPLES COLONY FSD 98 041-9220133 – 041-9220346 8 UBL SARGODHA ROAD FSD 581 041-9210344 – 35 9 UBL SAMAN ABAD FSD 1286 041-2661867 041-2660092 10 UBL DIJKOT 260 041-2670031 11 UBL JARANWALA 36 041-4312983/0414311126 12 UBL SAMUNDRI 326 041-3421585 041-3421657 13 UBL CHAK JHUMRA 99 041-8761131 14 UBL KHURRIANWALA 429 041-4360429/041-4364050 15 UBL SATANA BANGLA 1066 041-4600804 16 UBL TANDLIANWALA 518 041-3441548 17 UBL SALAR WALA 722 041-8742084 18 UBL MAMU KANJAN 37 041-3431452 19 UBL KHIDDAR WALA 1590 041-3413005 20 UBL THIKRIWALA 433 041-0255018 21 UBL MUREED WALA 1332 041-3472529 22 UBL SHAHEED ROAD JHANG 217 0477613829 23 UBL SHORKOT CANT 430 047-5500281 24 UBL GARH MAHA RAJA 359 047-5320506 25 UBL TOBA TEK SINGH 324 046-2511958 26 UBL GOJRA 404 046-35160062 27 UBL KAMALIA 970 046-3413830 28 UBL PIR MAHAL 545 046-3361272 29 UBL CHITIANA 668 046-2545363 30 UBL RAJANA 1093 046-2262201 – 2261588 31 UBL CHENAB NAGAR 153 047-6334576 32 UBL LALIAN 154 04533-610225 33 UBL CHINIOT 225 047-6213676 34 UBL BHOWANA 726 047-6201017 35 UBL WASU (18 HAZARI) 738 047-7645075 36 UBL SATELLITE TOWN JHANG 440 047-9200254 BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE & SECONDARY EDUCATION FAISALABAD BRANCHES OF MCB TO COLLECT BOARD’S DUES (ACCOUNT # (0485923691000100) PK 365 GOLD SR.# NAME OF BANK BRANCH CODE PHONE. -

Annexure I LIST of DESIGNATED BRANCHES

Annexure I LIST OF DESIGNATED BRANCHES Sr. Branch Branch Name Branch Address Province City No. Code 1 0001 Multan Main 126-C, Old Bahawalpur Road, Multan Punjab Multan 2 0002 Lahore Main 87-Shahrah-e-Quaid-e-Azam, Lahore Punjab Lahore 3 0003 Faisalabad Bank Square, Outside Kutchary Bazar, Faisalabad. Punjab Faisalabad Plot / Property No. B1-16S-3A, Opposite Telephone Exchange 4 0005 Sialkot Punjab Sialkot Office, Paris Road Sialkot. 5 0009 Sahiwal Plot 271, Block 2, High Street, Jinnah Road, Sahiwal. Punjab Sahiwal 6 0010 Sheikhupura B-IX-64-95/A, Near Sharif Plaza, Sargodha Road. Sheikhupura. Punjab Sheikhupra 7 0011 Gulberg 23 A / K, Gulberg-II, Lahore. Punjab Lahore Ground Floor, Soufi Hotel, Adjacent Faisal Cinema, G.T.Road, 8 0012 Gujrat Punjab Gujrat Gujrat. 9 0014 Galla Mandi , Multan 135/C, Ghalla Mandi, Vehari Road, Multan. Punjab Multan 10 0016 Rahim Yar Khan Shahi Road, Rahim Yar Khan Punjab Rahim Yar Khan 897-898 Block D, Moulana Shoukat Ali Road, Faisal Town, Peco 11 0018 Peco Road Punjab Lahore Road, Lahore 51,S-E Vohra Building , Outside Akbari Gate, Circular Road 12 0019 Circular Road Punjab Lahore Lahore. 13 0022 Defence 82 Y Commercial Phase III, Defence Housing Authority, Lahore Punjab Lahore 14 0024 Dera Ghazi Khan 83-New College Road, Block# 10, D.G.Khan. Punjab D.G Khan 15 0025 Sadiqabad Plot No. 24-25, Allama Iqbal Road, Sadiqabad Punjab Sadiqabad 16 0027 Khanpur Plot # 362-B Model Town Kutchery Road Khanpur. Punjab Khanpur 17 0028 Burewala 67/F, Vehari Bazar, Vehari Road, Burewala Punjab Burewala Plot No.