German Attitude Toward the Vatican 1933-1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8079K See Change Briefing Paper

CatholicCatholicTheThe ChurchChurch atat thetheUnitedUnited NationsNations Church or ?State? The Catholic It is the world’s smallest “city-state” at 108.7 acres. It houses the infrastructure of the Roman church at the UN: Catholic church: the pope’s palace, St. Peter’s A religion or a state? Basilica, offices and administrative services and libraries and archives.2 Vatican City was created Many questions have been raised about the role in 1929 under a treaty signed between Benito of the Catholic church at the United Nations Mussolini and Pietro Cardinale Gasparri, as a result of its high-profile and controversial secretary of state to Pope Pius XI.The Lateran role at international conferences. Participating Treaty was designed to compensate the pope as a full-fledged state actor in these for the 1870 annexation of the Papal States, conferences, the Holy See often goes against which consisted of 17,218 square miles in the overwhelming consensus of member states central Italy, and to guarantee the “indisputable “The Holy See is and seeks provisions in international documents sovereignty” of the Holy See by granting it a TheThe “See“See Change”Change” that would limit the health and rights of all not a state, but is physical territory.3 According to Archbishop Campaign people, but especially of women. How did the accepted as being Campaign Hyginus Eugene Cardinale, a former Vatican Holy See, the government of the Roman on the same footing Hundreds of organizations and thousands of people diplomat who wrote the authoritative work on Catholic -

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

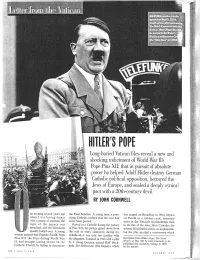

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Pius XII on Trial

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Pius XII on Trial Katherine M. Campbell University of Maine - Main, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Katherine M., "Pius XII on Trial" (2014). Honors College. 159. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/159 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PIUS XII ON TRIAL by Katherine M. Campbell A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology and Political Science) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: Henry Munson, Professor of Anthropology Alexander Grab, Professor of History Mark D. Brewer, Associate Professor of Political Science Richard J. Powell, Associate Professor of Political Science, Leadership Studies Sol Goldman, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science Copyright 2014 Katherine M. Campbell Abstract: Scholars have debated Pope Pius XII’s role in the Holocaust since the 1960s. Did he do everything he could and should have done to save Jews? His critics say no because of antisemitism rooted in the traditional Catholic views. His defenders say yes and deny that he was an antisemite. In my thesis, I shall assess the arguments on both sides in terms of the available evidence. I shall focus both on what Pius XII did do and what he did not do and on the degree to which he can be held responsible for the actions of low-level clergy. -

Learning from the Aftermath of the Holocaust G

Learning From The Aftermath Of The Holocaust G. Short, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, United Kingdom International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research [IJHLTR], Volume 14, Number 2 – Spring/Summer 2017 Historical Association of Great Britain www.history.org.uk ISSN: 14472-9474 Abstract: In this article I seek to encourage those involved in Holocaust education in schools to engage not just with the Holocaust but also with its aftermath. I conceptualise the latter in terms of two questions; namely, what happened to those Jews who survived the Nazi onslaught and what became of the perpetrators? British researchers in the field of Holocaust education have largely ignored these questions, discovering only that many schools ignore them too. I argue that students are able to benefit in a number of ways from learning about the aftermath of the Holocaust, for the topic provides a sense of closure, allows for a more sophisticated understanding of the fate of European Jewry between 1933 and 1945 and also has the potential to promote responsible citizenship. Keywords: Citizenship, Curriculum, Holocaust Aftermath, Learning, Teaching INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HISTORICAL LEARNING, TEACHING AND RESEARCH Vol. 14.2 LEARNING FROM THE AFTERMATH OF THE HOLOCAUST G. Short, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, United Kingdom Abstract: In this article I seek to encourage those involved in Holocaust education in schools to engage not just with the Holocaust but also with its aftermath. I conceptualise the latter in terms of two questions; namely, what happened to those Jews who survived the Nazi onslaught and what became of the perpetrators? British researchers in the field of Holocaust education have largely ignored these questions, discovering only that many schools ignore them too. -

GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, and the RECONSTRUCTION of CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented In

NEW CITIZENS: GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alison Clark Efford, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Professor John L. Brooke, Adviser Approved by Professor Mitchell Snay ____________________________ Adviser Professor Michael L. Benedict Department of History Graduate Program Professor Kevin Boyle ABSTRACT This work explores how German immigrants influenced the reshaping of American citizenship following the Civil War and emancipation. It takes a new approach to old questions: How did African American men achieve citizenship rights under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments? Why were those rights only inconsistently protected for over a century? German Americans had a distinctive effect on the outcome of Reconstruction because they contributed a significant number of votes to the ruling Republican Party, they remained sensitive to European events, and most of all, they were acutely conscious of their own status as new American citizens. Drawing on the rich yet largely untapped supply of German-language periodicals and correspondence in Missouri, Ohio, and Washington, D.C., I recover the debate over citizenship within the German-American public sphere and evaluate its national ramifications. Partisan, religious, and class differences colored how immigrants approached African American rights. Yet for all the divisions among German Americans, their collective response to the Revolutions of 1848 and the Franco-Prussian War and German unification in 1870 and 1871 left its mark on the opportunities and disappointments of Reconstruction. -

Switzerland 4Th Periodical Report

Strasbourg, 15 December 2009 MIN-LANG/PR (2010) 1 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Fourth Periodical Report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter SWITZERLAND Periodical report relating to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages Fourth report by Switzerland 4 December 2009 SUMMARY OF THE REPORT Switzerland ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (Charter) in 1997. The Charter came into force on 1 April 1998. Article 15 of the Charter requires states to present a report to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe on the policy and measures adopted by them to implement its provisions. Switzerland‘s first report was submitted to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in September 1999. Since then, Switzerland has submitted reports at three-yearly intervals (December 2002 and May 2006) on developments in the implementation of the Charter, with explanations relating to changes in the language situation in the country, new legal instruments and implementation of the recommendations of the Committee of Ministers and the Council of Europe committee of experts. This document is the fourth periodical report by Switzerland. The report is divided into a preliminary section and three main parts. The preliminary section presents the historical, economic, legal, political and demographic context as it affects the language situation in Switzerland. The main changes since the third report include the enactment of the federal law on national languages and understanding between linguistic communities (Languages Law) (FF 2007 6557) and the new model for teaching the national languages at school (—HarmoS“ intercantonal agreement). -

Europe in the Year 2030: “Digital Technology, Active Citizenship, and the Society of the Future” (Berlin, 4Th - 9Th January 2011)

- Cultural Diplomacy in Europe - A Forum for Young Leaders - Europe in the Year 2030: “Digital Technology, Active Citizenship, and the Society of the Future” (Berlin, 4th - 9th January 2011) A program of lectures and workshops exploring: • The Political Composition of the European Union in 2030: New Members, Former Members? • The Role of Digital Technology in the Society of the Future • The Use of Soft Power and Cultural Diplomacy by National States and the European Union • Bridging the Gap Between EU Institutions and the General Public: Active Citizenship ***** Participants of the program will also take part in: "The Future of EU Foreign Policy: An International Conference on the Political, Economic and Cultural Dimensions of EU Foreign Policy" (Berlin, 4th - 6th January 2011/ www.icd-euforeignpolicy.org) Speakers for the Conference include: Ana Trisic Babic; Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Bosnia & Herzegovina Prof. Dr. Davorin Kračun; Former Minister for Economic Relations and Development of Slovenia, Former Foreign Minister, Former Deputy Prime Minister Dr. Emil Constantinescu; Former President of Romania Erna Hennicot Schoepges; Former Luxembourgian Minister of Culture and Religious Affairs Dr. Erhard Busek; Former Vice-Chancellor of Austria, Former Minister for Education & Cultural Affairs Gerassimos D. Arsenis; Former Minister of Economics of Greece, Former Minister of Education and Former Minister of Defence Dr. Jacques F. Poos; Former Deputy Prime Minister of Luxembourg, Minister of Foreign Affairs Jytte Hilden; Former Minister of Culture of Denmark Prof. Dr. Lufter Xhuveli; Former Albanian Minister of Environment Mirko Tomassoni; Former Captain Regent of San Marino Prof. Dr. Ulrich Brückner; Jean Monnet Professor for European Studies, Stanford University in Berlin Prof. -

Welcome to the Heart of Europe Find out | Invest | Reap the Benefits More Than 2,800 Advertising Boards in 16 German Cities Promoted Erfurt in 2014/2015

Welcome to the heart of Europe Find out | Invest | Reap the benefits More than 2,800 advertising boards in 16 German cities promoted Erfurt in 2014/2015. The confident message of this campaign? Erfurt is growing and continues to develop at a rapid pace. Inhalt Contents A city at the heart of the action. Erfurt is growing 2 In the heart of Germany. Location and transport links 4 A growing city. Projects for the future 6 Reinventing the heart of the city. ICE-City Erfurt 8 On fertile soil. Industry in Erfurt 10 Already bearing fruit. Leading companies 12 A region ready for take-off. The Erfurt economic area 16 A meeting place in the heart of Europe. Conferences and conventions 18 A passion for teaching and research. Campus Thuringia 20 A city to capture your heart. Life in Erfurt 24 Welcome to Erfurt. Advice and contact details 28 | 1 Erfurt is growing A city at the heart of the action. Land area of Erfurt: 269 km2 2 | Erfurt is growing Erfurt is going places! It’s not for nothing that the Cologne Insti- Most of the old town has been restored The many companies that have moved tute for Economic Research named Erfurt and combines medieval charm with the to Erfurt in recent years are making this among the ten most dynamic cities in buzz of an urban centre. possible. Germany in its 2014 rankings. You can see Erfurt, the regional capital of Thuringia, the changes everywhere and sense a spirit is a prime hotspot for development and, ‘Erfurt is growing’ is therefore the confi- of dynamism: all kinds of housing projects as such, offers the many young people who dent message that is currently being heard are being built across the city, new hotels choose to settle here excellent prospects all over Germany. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

When Die Zeit Published Its Review of Decision Before Dawn

At the Front: common traitors in West German war films of the 1950s Article Accepted Version Wölfel, U. (2015) At the Front: common traitors in West German war films of the 1950s. Modern Language Review, 110 (3). pp. 739-758. ISSN 0026-7937 doi: https://doi.org/10.5699/modelangrevi.110.3.0739 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/40673/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5699/modelangrevi.110.3.0739 Publisher: Modern Humanities Research Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online AT THE FRONT: COMMON TRAITORS IN WEST GERMAN WAR FILMS OF THE 1950s Erst im militärischen Geheimnis kommt das Staatsgeheimnis zu sich selbst; da der Krieg als permanenter und totaler Zustand vorausgesetzt wird, läßt sich jeder beliebige Sachverhalt unter militärische Kategorien subsumieren: dem Feind gegenüber hat alles als Geheimnis und jeder Bürger als potentieller Verräter zu gelten. (HANS MAGNUS ENZENSBERGER) Die alten Krieger denken immer an die Kameraden, die gefallen sind, und meinen, ein Deserteur sei einer, der sie verraten hat. (LUDWIG BAUMANN) Introduction Margret Boveri, in the second volume of her treatise on Treason in the 20th Century, notes with respect to German resistance against National Socialism that the line between ethically justified and unethical treason is not easily drawn.1 She cites the case of General Hans Oster, deputy head of the Abwehr under Admiral Canaris. -

Saint Petersburg State University Joint Seed Money Funding Scheme

Call for Proposals 2018 Freie Universität Berlin – Saint Petersburg State University Joint Seed Money Funding Scheme With the goal of facilitating cooperation in the framework of a strategic partnership, Freie Universität Berlin (FUB) and Saint Petersburg State University (SPSU) have established a joint seed money funding scheme. The funding shall enable FUB and SPSU faculty and researchers to identify complementary strengths, facilitate the use of synergies, increase joint research, high level publications, academic mobility, and promote the development of outstanding future research projects. The joint funding scheme with an annual budget of € 40.000 (equivalent in roubles, respectively) aims at supporting the first steps of research collaboration. The following formats are possible: • Intensive research workshops • Short term research stays (for young as well as established researchers) • Research-oriented teaching / short intensive graduate seminars • Mobility for the preparation of joint research proposals The supported activities should have a clearly defined focus and serve as a catalyst for the development of new joint projects. The activities can take place in Berlin or in Saint Petersburg; participants should include both senior and junior faculty/researchers of FUB and SPSU. Maximum funding per proposal is € 10.000 (equivalent in roubles respectively). The motivation for holding the activity should be clearly explained, including how the involved FUB and SPSU institutes or departments can profit long term from this cooperation and what synergies can arise. Inclusion of German non-university research institutions such as Max Planck Institutes, Helmholtz Centers, and others as well as Russian institutions, is encouraged, however, the additional costs must be covered by these partners themselves.