American Catholicism and the Political Origins of the Cold War/ Thomas M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of St. Joseph's Seminary, Dunwoodie

2021 BULLETIN ST.JOSEPH’S SEMINARY DUNWOODIE A Message from the Rector s St. Joseph’s Seminary enters its 125th anniversary year, communion, proclaiming the A it is a special joy to share with you information about Word of God with imagination our programs of priestly formation and theological study. “We and fidelity to the teachings of stand on the shoulders of giants,” as the old saying goes. But the Church and shepherding today we also work alongside faithful men and women, highly local communities with ad- competent scholars who utilize the best delivery systems to ministrative competence and a open up the vast resources of the Catholic intellectual tradition capacity to welcome people of for our students. As an auxiliary bishop of one of the partici- all backgrounds into their local communities. pating dioceses of the St. Charles Borromeo Inter-diocesan Our priestly formation program includes seminarians from Partnership, I am grateful to Cardinal Timothy Michael Dolan the three partnership dioceses, the Dioceses of Bridgeport, CT. (Archbishop of New York), Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio (Dio- and Camden, NJ, the Ukrainian Eparchy of Stamford, and cese of Brooklyn) and Bishop John Barres (Diocese of Rockville candidates from religious communities and societies of apos- Centre) for their collaboration in training our future priests, tolic life. The presence of Franciscan Friars of the Renewal, permanent deacons and lay leaders and catechists for the local Idente Missionaries and Piarist Fathers and Brothers allows churches over which they preside. For the past nine years, St. for a sharing of charisms that deepens our appreciation of the Joseph’s Seminary has offered graduate programs in theology Church’s missionary agenda. -

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania Chapter 1. The Origin of the Polish Nation.................................3 Chapter 2. The Piast Dynasty...................................................4 Chapter 3. Lithuania until the Union with Poland.........................7 Chapter 4. The Personal Union of Poland and Lithuania under the Jagiellon Dynasty. ..................................................8 Chapter 5. The Full Union of Poland and Lithuania. ................... 11 Chapter 6. The Decline of Poland-Lithuania.............................. 13 Chapter 7. The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania : The Napoleonic Interlude............................................................. 16 Chapter 8. Divided Poland-Lithuania in the 19th Century. .......... 18 Chapter 9. The Early 20th Century : The First World War and The Revival of Poland and Lithuania. ............................. 21 Chapter 10. Independent Poland and Lithuania between the bTwo World Wars.......................................................... 25 Chapter 11. The Second World War. ......................................... 28 Appendix. Some Population Statistics..................................... 33 Map 1: Early Times ......................................................... 35 Map 2: Poland Lithuania in the 15th Century........................ 36 Map 3: The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania ........................... 38 Map 4: Modern North-east Europe ..................................... 40 1 Foreword. Poland and Lithuania have been linked together in this history because -

David Goldstein and Martha Moore Avery Papers 1870-1958 (Bulk 1917-1940) MS.1986.167

David Goldstein and Martha Moore Avery Papers 1870-1958 (bulk 1917-1940) MS.1986.167 http://hdl.handle.net/2345/4438 Archives and Manuscripts Department John J. Burns Library Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill 02467 library.bc.edu/burns/contact URL: http://www.bc.edu/burns Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Biographical note: David Goldstein .............................................................................................................. 6 Biographical note: Martha Moore Avery ...................................................................................................... 7 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................... 11 I: David Goldstein -

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

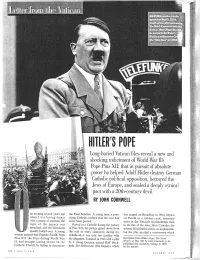

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Katholisches Wort in Die Zeit 45. Jahr März 2014

Prof. Dr. Konrad Löw: Pius XII.: „Bleibt dem katholischen Glauben treu!“ 68 Gerhard Stumpf: Reformer und Wegbereiter in der Kirche: Klemens Maria Hofbauer 76 Franz Salzmacher: Europa am Scheideweg 82 Katholisches Wort in die Zeit 45. Jahr März 2014 DER FELS 3/2014 65 Formen von Sexualität gleich- Liebe Leser, wertig sind. Eine Vorgeschichte hat weiterhin die Insolvenz des kircheneigenen Unternehmens der Karneval ist in der katho- „Weltbild“. Das wirtschaftliche lischen Welt zuhause, wo sich Desaster ist darauf zurückzufüh- der Rhythmus des Lebens auch ren, dass die Geschäftsführung im Kirchenjahr widerspiegelt. zu spät auf das digitale Geschäft Die Kirche kennt eben die Natur gesetzt hat. Hinzu kommt die INHALT des Menschen und weiß, dass er Sortimentsausrichtung, die mit auch Freude am Leben braucht. Esoterik, Pornographie und sa- tanistischer Literatur, trotz vie- Papst Franziskus: Lebensfreude ist nicht gera- Das Licht Christi in tiefster Finsternis ....67 de ein Zeichen, das unsere Zeit ler Hinweise über Jahrzehnte, charakterisiert. Die zunehmen- keineswegs den Anforderungen Prof. Dr. Konrad Löw: : den psychischen Erkrankungen eines kircheneigenen Medien- Pius XII.: „Bleibt dem sprechen jedenfalls nicht dafür. unternehmens entsprach. Eine katholischen Glauben treu!“ .................68 „Schwermut ist die Signatur der Vorgeschichte hat schließlich die Gegenwart geworden“, lautet geistige Ausrichtung des ZDK Raymund Fobes: der Titel eines Artikels, der die- und der sie tragenden Großver- Seid das Salz der Erde ........................72 ser Frage nachgeht (Tagespost, bände wie BDKJ, katholische 1.2.14). Frauenverbände etc. Prälat Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Lothar Roos: Die Menschen erleben heute, Die selbsternannten „Refor- „Ein Licht für das Leben mer“ der deutschen Ortskirche in der Gesellschaft“ (Lumen fidei) .........74 dass sie mit verdrängten Prob- lemen immer mehr in Tuchfüh- ereifern sich immer wieder ge- Gerhard Stumpf: lung kommen. -

Pius XII on Trial

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Pius XII on Trial Katherine M. Campbell University of Maine - Main, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Katherine M., "Pius XII on Trial" (2014). Honors College. 159. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/159 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PIUS XII ON TRIAL by Katherine M. Campbell A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology and Political Science) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: Henry Munson, Professor of Anthropology Alexander Grab, Professor of History Mark D. Brewer, Associate Professor of Political Science Richard J. Powell, Associate Professor of Political Science, Leadership Studies Sol Goldman, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science Copyright 2014 Katherine M. Campbell Abstract: Scholars have debated Pope Pius XII’s role in the Holocaust since the 1960s. Did he do everything he could and should have done to save Jews? His critics say no because of antisemitism rooted in the traditional Catholic views. His defenders say yes and deny that he was an antisemite. In my thesis, I shall assess the arguments on both sides in terms of the available evidence. I shall focus both on what Pius XII did do and what he did not do and on the degree to which he can be held responsible for the actions of low-level clergy. -

Ursulines of the Eastern Province SPRING 2011

Ursulines of the Eastern Province SPRING 2011 BylinesIn March 2010, I spent CARRYING ON: time in the English Province Archives WORLD WAR II AND outside London, reading the later diaries THE URSULINES IN ROME of Mother Magdalen Martha Counihan, OSU who had been born in 1891, an Anglican in India. She converted uring World War II, like many other to Catholicism as a Roman institutions and convents, the young woman, was DUrsuline community at the Generalate a suffragette, then Ilford Archives, Photo courtesy English Province in Rome provided sanctuary to hunted Jews and worked in British Mother Magdalen Bellasis, OSU political dissidents. I spent a fall sabbatical from Intelligence during my ministry as Archivist and Special Collections WWI (for which she Librarian at the College of New Rochelle in received the prestigious award of Member of the British research on this topic. Empire), and entered the Ursulines at the age of 28. My interest had begun when I read the typescript Magdalen was a gifted person. Soon after profession in of the English Ursuline, Mother Magdalen Bellasis, 1922, she was sent to Oxford where she received both a who was the prioress of the community in Rome BA and an MA. She served as a school headmistress and from 1935-1945. The general government was in then novice mistress in England before going to Rome exile in the U.S.; few letters could be sent, and for tertianship in 1934. A year later she was appointed fewer arrived. The nuns were cut off from one prioress of the generalate community. -

Chapter 18: Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1933-1939

Roosevelt and the New Deal 1933–1939 Why It Matters Unlike Herbert Hoover, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was willing to employ deficit spending and greater federal regulation to revive the depressed economy. In response to his requests, Congress passed a host of new programs. Millions of people received relief to alleviate their suffering, but the New Deal did not really end the Depression. It did, however, permanently expand the federal government’s role in providing basic security for citizens. The Impact Today Certain New Deal legislation still carries great importance in American social policy. • The Social Security Act still provides retirement benefits, aid to needy groups, and unemployment and disability insurance. • The National Labor Relations Act still protects the right of workers to unionize. • Safeguards were instituted to help prevent another devastating stock market crash. • The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation still protects bank deposits. The American Republic Since 1877 Video The Chapter 18 video, “Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal,” describes the personal and political challenges Franklin Roosevelt faced as president. 1928 1931 • Franklin Delano • The Empire State Building 1933 Roosevelt elected opens for business • Gold standard abandoned governor of New York • Federal Emergency Relief 1929 Act and Agricultural • Great Depression begins Adjustment Act passed ▲ ▲ Hoover F. Roosevelt ▲ 1929–1933 ▲ 1933–1945 1928 1931 1934 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ 1930 1931 • Germany’s Nazi Party wins • German unemployment 1933 1928 107 seats in Reichstag reaches 5.6 million • Adolf Hitler appointed • Alexander Fleming German chancellor • Surrealist artist Salvador discovers penicillin Dali paints Persistence • Japan withdraws from of Memory League of Nations 550 In this Ben Shahn mural detail, New Deal planners (at right) design the town of Jersey Homesteads as a home for impoverished immigrants. -

Blessed Sacrament Church "I Am the Living Bread Come Down from Heaven

Blessed Sacrament Church "I am the Living Bread come down from Heaven. If any man eats of this Bread, he shall live forever; and the Bread I will give, is My Flesh." John 6:51-52 SCHEDULE OF MASSES LORD’S DAY: Saturday: 4:00 p.m. Sunday: 8:00 and 10:30 a.m. HOLYDAYS: Vigil: 6:00 p.m. Holyday: 7:00 a.m. & 9:00 a.m. WEEKDAYS: 9:00 a.m. SATURDAYS: First Saturdays only: 8:00 a.m. SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION: Saturday 2:45 to 3:30 p.m. and by appointment BAPTISM: As part of the preparation process an interview with the Pastor and two instructional sessions are required. Please contact the rectory to schedule. ENGAGED COUPLES: Arrangements for your marriage must be made at least nine months in advance of the marriage date. NEW PARISHIONERS: We welcome you and ask that you register at the Rectory. We want to know and serve you! We hope that you will favor your parish with your prayers, your presence and your talents. Pastor Rev. Timothy J. Campoli Church Rectory 221 Federal Street 182 High Street Greenfield, MA 01301 Greenfield, MA 01301 blessedsacramentgreenfieldma.org (413) 773-3311 Deacons Deacon John Leary Deacon George Nolan (413) 219-2734 (C) (508) 304-2763 (C) [email protected] [email protected] Director of Organist Religious Education Choir Director Laurie Tilton Stephen Glover 774-2918 772-0532 [email protected] Alternatives Pregnancy Ctr. Calvary Cemetery Pregnancy Tests, Counseling, Support Wisdom Way Post Abortion Support Greenfield (413) 774-6010 773-3311 “Whosoever shall eat this Bread, or drink this Hispanic Ministry Sr. -

Kenneth A. Merique Genealogical and Historical Collection BOOK NO

Kenneth A. Merique Genealogical and Historical Collection SUBJECT OR SUB-HEADING OF SOURCE OF BOOK NO. DATE TITLE OF DOCUMENT DOCUMENT DOCUMENT BG no date Merique Family Documents Prayer Cards, Poem by Christopher Merique Ken Merique Family BG 10-Jan-1981 Polish Genealogical Society sets Jan 17 program Genealogical Reflections Lark Lemanski Merique Polish Daily News BG 15-Jan-1981 Merique speaks on genealogy Jan 17 2pm Explorers Room Detroit Public Library Grosse Pointe News BG 12-Feb-1981 How One Man Traced His Ancestry Kenneth Merique's mission for 23 years NE Detroiter HW Herald BG 16-Apr-1982 One the Macomb Scene Polish Queen Miss Polish Festival 1982 contest Macomb Daily BG no date Publications on Parental Responsibilities of Raising Children Responsibilities of a Sunday School E.T.T.A. BG 1976 1981 General Outline of the New Testament Rulers of Palestine during Jesus Life, Times Acts Moody Bible Inst. Chicago BG 15-29 May 1982 In Memory of Assumption Grotto Church 150th Anniversary Pilgrimage to Italy Joannes Paulus PP II BG Spring 1985 Edmund Szoka Memorial Card unknown BG no date Copy of Genesis 3.21 - 4.6 Adam Eve Cain Abel Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 4.7- 4.25 First Civilization Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 4.26 - 5.30 Family of Seth Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 5.31 - 6.14 Flood Cainites Sethites antediluvian civilization Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 9.8 - 10.2 Noah, Shem, Ham, Japheth, Ham father of Canaan Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 10.3 - 11.3 Sons of Gomer, Sons of Javan, Sons -

Religious Basis of U.S. Law Uader Attack, Expert Warns

Moscow Chapel fo Get Flag From U.S. Capitol Religious Basis of U.S. Law Washington.—An American hope for all people who yearn flag that has flown over the for tre^om . It is more than CapiUd Jbuildi^ will adorn a a challenge to those who seek Catholic chapel in Moscow. to dominate and control the The reqi^est was made by Fa lives and souls of men. “To you, to the personnel of Uader Attack, Expert Warns ther Joseph Richard, A.A., at the American Embassy, and a meeting with U.S. Sen. Hu to the people of the Soviet New York.—“A powerful, well-financed bert Humphrey (Minn.), be- Union, I send this flag with group in America” is “seeking by court action to Bishop Shoon Soys fmre leaving for Moscow to as the wish that it be seen as a a a /waaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaau sume bis duties as chapiain at a symbol of America’s love destroy every moral support whidh the state now the Uil. Embassy. for freedom, America’s quest bestows on religion,” charged Father Robert F. In a letter to the chaplain, for peace, and America’s con Senator Humphrey said: cern for the progress of all Drinan, S.J., dean of Boston College Law School. Softening “This flag is a message of peoples.” In a sermon at the 33rd annual Red M*ass sponsored by the New York Supplement to the Denver Catholic Register Guild of Catholic Lawyers, Fa Of Morality ther Drinan warned that this N atio n al group is attempting to persuade National the judiciary that America must Seen in d.S. -

An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church Under Communism Kathryn Burns Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2013 More Catholic than the Pope: An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church under Communism Kathryn Burns Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the European History Commons Recommended Citation Burns, Kathryn, "More Catholic than the Pope: An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church under Communism" (2013). Honors Theses. 638. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/638 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “More Catholic than the Pope”: An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church under Communism By Kathryn Burns ******************** Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE June 2013 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………..........................................1 Chapter I. The Roman Catholic Church‟s Influence in Poland Prior to World War II…………………………………………………………………………………………………...4 Chapter II. World War II and the Rise of Communism……………….........................................38 Chapter III. The Decline and Demise of Communist Power……………….. …………………..63 Chapter IV. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….76 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..78 ii Abstract Poland is home to arguably the most loyal and devout Catholics in Europe. A brief examination of the country‟s history indicates that Polish society has been subjected to a variety of politically, religiously, and socially oppressive forces that have continually tested the strength of allegiance to the Catholic Church.