Pius XII on Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John XXIII & Idea of a Council

POPE JOHN XXIII AND THE IDEA OF AN ECUMENICAL COUNCIL Joseph A. Komonchak On January 25, 1959, just three months after he had assumed the papacy, Pope John XXIII informed a group of Cardinals at St. Paul's outside the Walls that he intended to convoke an ecumenical council. The announcement appeared towards the end of a speech closing that year's celebration of the Chair of Unity Octave, which the Pope used in order to comment on his initial experiences as Pope and to meet the desire to know the main lines his pontificate would follow.1 The first section offered what might be called a pastoral assessment of the challenges he faced both as Bishop of Rome and as supreme Pastor of the universal Church. The reference to his responsibilities as Bishop of Rome is already significant, given that this local episcopal role had been greatly eclipsed in recent centuries, most of the care for the city having been assigned to a Cardinal Vicar, while the pope focused on universal problems. Shortly after his election, Pope John had told Cardinal Tardini that he intended to be Pope "quatenus episcopus Romae, as Bishop of Rome." With regard to the city, the Pope noted all the changes that had taken place since in the forty years since he had worked there as a young priest. He noted the great growth in the size and population of Rome and the new challenges it placed on those responsible for its spiritual well-being. Turning to the worldwide situation, the Pope briefly noted that there was much to be joyful about. -

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

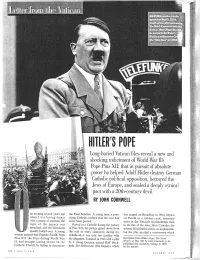

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Download the History Book In

GHELLA Five Generations of Explorers and Dreamers Eugenio Occorsio in collaboration with Salvatore Giuffrida 1 2 Ghella, Five Generations of Explorers and Dreamers chapter one 1837 DOMENICO GHELLA The forefather Milan, June 1837. At that time around 500,000 people live in At the head of the city there is a new mayor, Milan, including the suburbs in the peripheral belt. Gabrio Casati. One of these is Noviglio, a rural hamlet in the south of the city. He was appointed on 2 January, the same day that Alessandro Manzoni married his second wife Teresa Borri, following the death of Enrichetta Blondel. The cholera epidemic of one year ago, which caused It is here, that on June 26 1837 Domenico Ghella more than 1,500 deaths, is over and the city is getting is born. Far away from the centre, from political life back onto its feet. In February, Emperor Ferdinand and the salon culture of the aristocracy, Noviglio is I of Austria gives the go-ahead to build a railway known for farmsteads, rice weeders, and storks which linking Milan with Venice, while in the city everyone come to nest on the church steeples from May to is busy talking about the arrival of Honoré de Balzac. July. A rural snapshot of a few hundred souls, living He is moving into the Milanese capital following an on the margins of a great city. Here Dominico spends inheritance and apparently, to also escape debts his childhood years, then at the age of 13 he goes to accumulated in Paris. France, to Marseille, where he will spend ten long years working as a miner. -

Mystici Corporis Christi

MYSTICI CORPORIS CHRISTI ENCYCLICAL OF POPE PIUS XII ON THE MISTICAL BODY OF CHRIST TO OUR VENERABLE BRETHREN, PATRIARCHS, PRIMATES, ARCHBISHOPS, BISHIOPS, AND OTHER LOCAL ORDINARIES ENJOYING PEACE AND COMMUNION WITH THE APOSTOLIC SEE June 29, 1943 Venerable Brethren, Health and Apostolic Benediction. The doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, which is the Church,[1] was first taught us by the Redeemer Himself. Illustrating as it does the great and inestimable privilege of our intimate union with so exalted a Head, this doctrine by its sublime dignity invites all those who are drawn by the Holy Spirit to study it, and gives them, in the truths of which it proposes to the mind, a strong incentive to the performance of such good works as are conformable to its teaching. For this reason, We deem it fitting to speak to you on this subject through this Encyclical Letter, developing and explaining above all, those points which concern the Church Militant. To this We are urged not only by the surpassing grandeur of the subject but also by the circumstances of the present time. 2. For We intend to speak of the riches stored up in this Church which Christ purchased with His own Blood, [2] and whose members glory in a thorn-crowned Head. The fact that they thus glory is a striking proof that the greatest joy and exaltation are born only of suffering, and hence that we should rejoice if we partake of the sufferings of Christ, that when His glory shall be revealed we may also be glad with exceeding joy. -

The Mediation of the Church in Some Pontifical Documents Francis X

THE MEDIATION OF THE CHURCH IN SOME PONTIFICAL DOCUMENTS FRANCIS X. LAWLOR, SJ. Weston College N His recent encyclical letter, Hurnani generis, of Aug. 12, 1950, the I Holy Father reproves those who "reduce to a meaningless formula the necessity of belonging to the true Church in order to achieve eternal salvation."1 In the light of the Pope's insistence in the same encyclical letter on the ordinary, day-by-day teaching office of the Roman Pontiffs, it will be useful to select from the infra-infallible but authentic teaching of the Popes some of the abundant material touching the question of the mediatorial function of the Church in the order of salvation. The Popes, to be sure, do not speak and write after the manner of theo logians but as pastors of souls, and it is doubtless not always easy to transpose to a theological level what is contained in a pastoral docu ment and expressed in a pastoral method of approach. Yet the authentic teaching of the Popes is both a guide to, and a source of, theological thinking. The documents cited are of varying solemnity and doctrinal importance; an encyclical letter is clearly of greater magisterial value than, let us say, an occasional epistle to some prelate. It is not possible here to situate each citation in its documentary context; but the force and point of a quotation, removed from its documentary perspective, is perhaps as often lessened as augmented. Those who wish may read them in their context, if they desire a more careful appraisal of evidence. -

Myron Charles Taylor Papers

Myron Charles Taylor Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Prepared by Anita L. Nolen Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2012 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2012 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms012159 Collection Summary Title: Myron Charles Taylor Papers Span Dates: 1928-1953 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1940-1950) ID No.: MSS42390 Creator: Taylor, Myron Charles, 1874-1959 Extent: 1250 items ; 8 containers ; 2.8 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Industrialist, diplomat, and lawyer. Correspondence, reports, and other papers documenting Taylor's activities as the president's personal representative to Pope Pius XII. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Cicognani, Amleto Giovanni, 1883-1973. Dibelius, Otto, 1880-1967. John XXIII, Pope, 1881-1963. Maglione, Luigi, 1877-1944. Oxnam, G. Bromley (Garfield Bromley), 1891-1963. Paul VI, Pope, 1897-1978. Pius XII, Pope, 1876-1958. Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 1882-1945. Tardini, Domenico, 1888-1961. Taylor, Myron Charles, 1874-1959. Truman, Harry S., 1884-1972. Organizations Catholic Church--Foreign relations--United States. Subjects Diplomatic and consular service, American--Vatican City. Places United States--Foreign relations--Catholic Church. Vatican City--History. Occupations Diplomats. Industrialists. Lawyers. -

Learning from the Aftermath of the Holocaust G

Learning From The Aftermath Of The Holocaust G. Short, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, United Kingdom International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research [IJHLTR], Volume 14, Number 2 – Spring/Summer 2017 Historical Association of Great Britain www.history.org.uk ISSN: 14472-9474 Abstract: In this article I seek to encourage those involved in Holocaust education in schools to engage not just with the Holocaust but also with its aftermath. I conceptualise the latter in terms of two questions; namely, what happened to those Jews who survived the Nazi onslaught and what became of the perpetrators? British researchers in the field of Holocaust education have largely ignored these questions, discovering only that many schools ignore them too. I argue that students are able to benefit in a number of ways from learning about the aftermath of the Holocaust, for the topic provides a sense of closure, allows for a more sophisticated understanding of the fate of European Jewry between 1933 and 1945 and also has the potential to promote responsible citizenship. Keywords: Citizenship, Curriculum, Holocaust Aftermath, Learning, Teaching INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HISTORICAL LEARNING, TEACHING AND RESEARCH Vol. 14.2 LEARNING FROM THE AFTERMATH OF THE HOLOCAUST G. Short, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, United Kingdom Abstract: In this article I seek to encourage those involved in Holocaust education in schools to engage not just with the Holocaust but also with its aftermath. I conceptualise the latter in terms of two questions; namely, what happened to those Jews who survived the Nazi onslaught and what became of the perpetrators? British researchers in the field of Holocaust education have largely ignored these questions, discovering only that many schools ignore them too. -

PRECONCILIAR VOTA and THEIR BACKGROUND 1. The

CHAPTER ONE PRECONCILIAR VOTA AND THEIR BACKGROUND 1. Th e Antepreparatory Vota Post recitationem epistulae ex parte Commissionis Antepraeparatoriae Concilii receptae, E. Decanus instanter petit ut singuli professores suas de rebus in Concilio propositiones notam faciant.1 Th ese words are to be found in the report of the Faculty Council meeting of Leuven’s Faculty of Th eology and Canon Law dated October 9, 1959. While it may appear to have little signifi cance, it serves nevertheless as an interesting point of departure for our study of the preparatory phases of Vatican II. A closer examination of the notes taken on the occasion by dean Joseph Coppens2 reveals that a circular letter from Cardinal Domenico Tardini3 had apparently been addressed to the rectors of the Catholic universities. Leuven’s rector van Waeyenbergh4 did little more than pass the letter—which invited the theological faculties of the Roman Catholic universities to make their wishes known to the Antepre- paratory Conciliar Commission5—on to the dean of the Th eology 1 CSVII ASFT, 1957–62, p. 44. 2 Joseph Coppens (1896–1981), priest of the diocese of Ghent, professor of Biblical Exegesis at the Leuven Th eological Faculty and dean of the Faculty. See Gustave ils,Th et al., ‘In Memoriam Monseigneur J. Coppens, 1896–1981,’ ETL 57 (1981), 227–340. 3 Domenico Tardini (1888–1961), Italian cardinal, appointed Vatican Secretary of State in 1958, and thus responsible for Extroardinary Ecclesiastical Aff airs. Tardini sent the circular letter as president of the Antepreparatory Commission. See Vincenzo Carbone, ‘Il cardinale Tardini e la preparazione del Concilio Vaticano II,’ RSCI 45 (1991), 42–88. -

Catholicism and the Holocaust

Catholicism and the Holocaust Books Aarons. Mark and John Loftus. Unholy Trinity: How the Vatican's Nazi Networks Betrayed Western Intelligence to the Soviets. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992. Chadwick, Owen. Britain and the Vatican During the Second World War. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988. Cianfarra, Camille Maximilian. The Vatican and the War. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1944. Delzell, Charles, ed. The Papacy and Totalitarianism between the Two World Wars. New York: Wiley, 1974. Dietrich, Donald J. Catholic Citizens in the Third Reich: Psycho-Social Principles and Moral Reasoning. New Brunswick, NJ : Transaction Books, 1988. Ehler, Sidney Z. and John B. Morrall, eds. Church and State Through the Centuries: A Collection of Historic Documents with Commentaries. New York: Biblo and Tannen, 1954. Falconi, Carlo. The Popes in the Twentieth Century: From Pius X to John XXIII. Boston: Little, Brown, 1967. Falconi, Carlo. The Silence of Pius XII. Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1965. Friedlander, Saul. Pius XII and the Third Reich: A Documentation. New York: Octagon Books, 1980. Graham, Robert A. Pius XII's Defense of Jews and Others: 1944-45 in Pius XII and the Holocaust: A Reader. Milwaukee: Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights, 1988. Holmes, J. Derek. The Papacy in the Modern World. New York: Crossroad, 1981. Jewish Federation for the Righteous. Voices and Views. Kent Peter C. and John F. Pollard, eds. Papal Diplomacy in the Modern Age. Westport, CT: Pareger, 1994. Lapide, Pinchas E. Three Popes and the Jews. New York: Hawthorne, 1967. Lehmann, Leo Hubert. Vatican Policy in the Second World War. -

American Catholicism and the Political Origins of the Cold War/ Thomas M

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1991 American Catholicism and the political origins of the Cold War/ Thomas M. Moriarty University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Moriarty, Thomas M., "American Catholicism and the political origins of the Cold War/" (1991). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1812. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1812 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN CATHOLICISM AND THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by THOMAS M. MORI ARTY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 1991 Department of History AMERICAN CATHOLICISM AND THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by THOMAS M. MORIARTY Approved as to style and content by Loren Baritz, Chair Milton Cantor, Member Bruce Laurie, Member Robert Jones, Department Head Department of History TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. "SATAN AND LUCIFER 2. "HE HASN'T TALKED ABOUT ANYTHING BUT RELIGIOUS FREEDOM" 25 3. "MARX AMONG THE AZTECS" 37 4. A COMMUNIST IN WASHINGTON'S CHAIR 48 5. "...THE LOSS OF EVERY CATHOLIC VOTE..." 72 6. PAPA ANGEL I CUS 88 7. "NOW COMES THIS RUSSIAN DIVERSION" 102 8. "THE DEVIL IS A COMMUNIST" 112 9. -

FORUM Holocaust Scholarship and Politics in the Public Sphere: Reexamining the Causes, Consequences, and Controversy of the Historikerstreit and the Goldhagen Debate

Central European History 50 (2017), 375–403. © Central European History Society of the American Historical Association, 2017 doi:10.1017/S0008938917000826 FORUM Holocaust Scholarship and Politics in the Public Sphere: Reexamining the Causes, Consequences, and Controversy of the Historikerstreit and the Goldhagen Debate A Forum with Gerrit Dworok, Richard J. Evans, Mary Fulbrook, Wendy Lower, A. Dirk Moses, Jeffrey K. Olick, and Timothy D. Snyder Annotated and with an Introduction by Andrew I. Port AST year marked the thirtieth anniversary of the so-called Historikerstreit (historians’ quarrel), as well as the twentieth anniversary of the lively debate sparked by the pub- Llication in 1996 of Daniel J. Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. To mark the occasion, Central European History (CEH) has invited a group of seven specialists from Australia, Germany, Great Britain, and the United States to comment on the nature, stakes, and legacies of the two controversies, which attracted a great deal of both scholarly and popular attention at the time. To set the stage, the following introduction provides a brief overview of the two debates, followed by some personal reflections. But first a few words about the participants in the forum, who are, in alphabetical order: Gerrit Dworok, a young German scholar who has recently published a book-length study titled “Historikerstreit” und Nationswerdung: Ursprünge und Deutung eines bundesrepublika- nischen Konflikts (2015); Richard J. Evans, a foremost scholar -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss .