When Die Zeit Published Its Review of Decision Before Dawn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

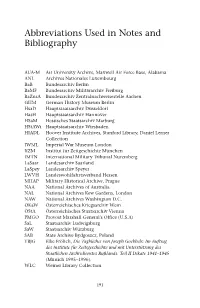

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

United States of America V. Erhard Milch

War Crimes Trials Special List No. 38 Records of Case II United States of America v. Erhard Milch National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, Washington, D.C. 1975 Special List No. 38 Nuernberg War Crimes Trials Records of Case II United States of America v. Erhard Milch Compiled by John Mendelsohn National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1975 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data United States. National Archives and Records Service. Nuernberg war crimes trial records. (Special list - National Archives and Records Service; no. 38) Includes index. l. War crime trials--N emberg--Milch case,l946-l947. I. Mendelsohn, John, l928- II. Title. III. Series: United States. National Archives and Records Service. Special list; no.38. Law 34l.6'9 75-6l9033 Foreword The General Services Administration, through the National Archives and Records Service, is· responsible for administering the permanently valuable noncurrent records of the Federal Government. These archival holdings, now amounting to more than I million cubic feet, date from the <;lays of the First Continental Congress and consist of the basic records of the legislative, judicial, and executive branches of our Government. The presidential libraries of Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson contain the papers of those Presidents and of many of their - associates in office. These research resources document significant events in our Nation's history , but most of them are preserved because of their continuing practical use in the ordinary processes of government, for the protection of private rights, and for the research use of scholars and students. -

Ilse Stöbe (1911 - 1942) Im Widerstand Gegen Das „Dritte Reich“

Ilse Stöbe (1911 - 1942) im Widerstand gegen das „Dritte Reich“. Berlin, den 27. August 2013 (korrigierte Fassung vom 20. September 2013) Dieses Gutachten wurde vom Institut für Zeitgeschichte, München-Berlin, im Auftrag des Auswärtigen Amtes erstellt. Gemäß dem von beiden Seiten am 21. Juni 2012 geschlossenen Vertrag erstreckt sich der Gegenstand dieses Gutachtens auf: 1. Ermittlung und Darstellung aller Handlungen, Tätigkeiten und Leistungen von Frau Ilse Stöbe, die sie als Vertreterin des Widerstandes gegen das „Dritte Reich“ ausweisen. 2. biografische Einzelheiten, die für eine persönliche Verstrickung von Ilse Stöbe in Unrechtstaten sprechen, bzw. biografische Einzelheiten, die dagegen sprechen könnten, dass das Auswärtige Amt künftig Ilse Stöbe in besonderer Weise als Widerständlerin gegen den Nationalsozialismus würdigt und an sie erinnert. Einleitung Ilse Stöbe wurde am 14. Dezember 1942 vom Reichskriegsgericht wegen Landesverrats zum Tode verurteilt und am 22. Dezember 1942, nachdem Hitler persönlich eine Begnadigung abgelehnt hatte, im Gefängnis Plötzensee mit dem Fallbeil hingerichtet. Ilse Stöbe hatte tatsächlich die sowjetische Militäraufklärung mit Informationen beliefert. Ihre sterblichen Reste wurden aller Wahrscheinlichkeit nach zu Forschungszwecken freigegeben, ein Grab existiert nicht. Die nutzbare Forschungsliteratur und Publizistik ist nicht sehr umfänglich und offenbart im Hinblick auf die Person Ilse Stöbes große Lücken. Die vorliegenden Darstellungen sind disparat und widersprechen sich teilweise in den Fakten -

The Abwehr : from German Espionage Agency, to Centre of Resistance Against Hitler Student: Greg Elder Sponsor: Dr

The Abwehr : From German espionage agency, to centre of resistance against Hitler Student: Greg Elder Sponsor: Dr. Vasilis Vourkoutiotis The Project: About the Abwehr: My research for Dr. Vourkoutiotis has mainly involved searching the microfilmed finding-aids for the German The name “Abwehr” in German can be translated literally as Captured Records archive located in Washington, D.C. The task requires me to scan the microfilmed data sheets “defence.” However, despite its name, the Abwehr became one of for information relevant to the project, and then summarize that info for the Professor. The process has greatly the forefront intelligence gathering establishments in Nazi Germany. familiarized me with the everyday work of a professional historian, and some of the necessary research steps for The organization was tasked with gathering information on the a historical monograph. The project has also furthered my knowledge of German history, especially regarding country’s enemies, primarily using field-based agents. The Abwehr the different espionage organizations at work during World War II. fell under the administration of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Supreme Command of the Armed Forces) and interacted heavily This work is in preparation for Dr. Vourkoutiotis’s eventual trip to the archives in Washington D.C. where he will with other German espionage agencies such as the locate the important documents relating to the Abwehr. The research completed by myself in Ottawa will enable Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service of the SS and Nazi Party). him to visit the archives already aware of what relevant documents exist, and where to begin in his search for primary sources. -

Responsibility for Future Generations (PDF)

THE POLITICAL RESPONSIBILITY OF THE CHURCH Responsibility for Future Generations PRIMING THE PUMP: When you think about the future the children of St. Andrew face, what fills you with foreboding? INTRODUCTION: “AFTER TEN YEARS” 1 1. Written at Christmas 1942, a few months prior to arrest on April 5, 1943 2. Addressed to co-conspirators a. Eberhard Bethge: student, confessing partner, and dear friend b. Hans von Dohnanyi: brother-in-law and mastermind of conspiracy c. Hans Oster: chief of Central Section in Military Intelligence Office 3. Included as Prologue in Letters and Papers from Prison a. Bridges gap between final months of freedom and imprisonment b. “New Year’s” reflection, taking stock of events of events and issues EXPOSING THE MASQUERADE OF EVIL 1. Nazis clothed themselves in “garb of relative historical and social justice” 2 2. In extreme situation like Nazi Germany may have to stand firm with truthful/responsible deeds rather than words 3. Failed attempts to stand firm a. Reasonable people: reason will fix things b. Fanatical people: attack evil with purity of principle c. People of conscience: torn apart by conflicting ethical factors d. Dutiful people: obey commands of those in authority e. People of freedom: value necessary deed more highly than untarnished conscience and reputation f. Privately virtuous: close eyes to injustices around them 4. Standing firm by engaging in responsible/truthful action a. Ultimate not reason, principles, conscience, duty, freedom, virtue b. Obedient and responsible action toward God and other humans c. Critiques any approach focused too exclusively on consequences, motives, or any one ethical factor d. -

Kirchubel on Citino, 'The Wehrmacht's Last Stand: the German Campaigns of 1944-1945'

H-War Kirchubel on Citino, 'The Wehrmacht's Last Stand: The German Campaigns of 1944-1945' Review published on Saturday, May 5, 2018 Robert M. Citino. The Wehrmacht's Last Stand: The German Campaigns of 1944-1945. Modern War Studies Series. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2017. Illustrations, maps. 632 pp. $34.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-7006-2494-2. Reviewed by Robert Kirchubel (Purdue University)Published on H-War (May, 2018) Commissioned by Margaret Sankey (Air War College) Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=51318 Robert M. Citino, presently at the National WWII Museum, has again teamed up with the University Press of Kansas for his latest installment on modern German military history. The Wehrmacht’s Last Stand investigates Germany’s final battles against the Soviet Union and the Western Allies to its east, south, and west. As we have come to expect from Citino, the book is thoroughly researched, clearly narrated, and tightly argued. While Wehrmacht’s Last Stand synthesizes a great number of secondary materials—a review of its bibliography reveals only a couple pre-1945 German military journals that could be considered primary sources—it is full of new insights and thought-provoking interpretations of key events in late World War II.[1] Citino takes military historians to school by demonstrating how operational history should be written, at a time when elements of the academy consider that subdiscipline passé and of doubtful utility. The Wehrmacht had a good run during the first two years of the war, then a couple years of transition (notably against the USSR), but in Wehrmacht’s Last Stand it is reeling backward on every front. -

Religious and Secular Responses to Nazism: Coordinated and Singular Acts of Opposition

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition Kathryn Sullivan University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Sullivan, Kathryn, "Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 891. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/891 RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR RESPONSES TO NAZISM COORDINATED AND SINGULAR ACTS OF OPPOSITION by KATHRYN M. SULLIVAN B.A. University of Central Florida, 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2006 © 2006 Kathryn M. Sullivan ii ABSTRACT My intention in conducting this research is to satisfy the requirements of earning a Master of Art degree in the Department of History at the University of Central Florida. My research aim has been to examine literature written from the 1930’s through 2006 which chronicles the lives of Jewish and Gentile German men, women, and children living under Nazism during the years 1933-1945. -

Mommsen, Hans, Germans Against Hitler

GERMANS AGAINST HITLER HANS MOMMSEN GERMANSGERMANSGERMANS AGAINSTAGAINST HITLERHITLER THE STAUFFENBERG PLOT AND RESISTANCE UNDER THE THIRD REICH Translated and annotated by Angus McGeoch Introduction by Jeremy Noakes New paperback edition published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com First published in hardback in 2003 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd as Alternatives to Hitler. Originally published in 2000 as Alternative zu Hitler – Studien zur Geschichte des deutschen Widerstandes. Copyright © Verlag C.H. Beck oHG, Munchen, 2000 Translation copyright © I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd, 2003, 2009 The translation of this work has been supported by Inter Nationes, Bonn. The right of Hans Mommsen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 978 1 84511 852 5 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library Project management by Steve Tribe, Andover Printed and bound in India by Thomson Press India Ltd ContentsContentsContents Preface by Hans Mommsen vii Introduction by Jeremy Noakes 1 1. Carl von Ossietzky and the concept of a right to resist in Germany 9 2. German society and resistance to Hitler 23 3. -

USAFA Harmon Memorial Lecture #27 Military Planning and National Policy: German Overtures to Two World Wars Harold C

'The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Air Force, Department of Defense or the US Government.'" USAFA Harmon Memorial Lecture #27 Military Planning and National Policy: German Overtures to Two World Wars Harold C. Deutsch, 1984 The celebrated dictum of Carl von Clausewitz that war is the continuation of policy has bred variants which, although not necessarily contradictory, approach the problem of war and peace rather differently. Social revolutionists, notably Lenin, like to switch emphasis by perceiving peace as a moderated form of conflict. Our concern here, the interplay between military planning and preparation for war with the form and con duct of national policy, has less to do with maxims than with actuality in human affairs. The backgrounds of the two world wars of our century tell us much about this problem. They also indicate how greatly accidents of circumstance and personality may play a role in the course of events. This was notably true of Germany whose fate provides the central thread for the epoch of the two world conflicts. At some future time they may yet be known historically as "the German Wars." This is not to infer that, had Germany not existed as a nation, and, let us say, France and Russia had been geographic neighbors, the first half of our century would have been an era of peace. Some of the factors that led to international stress would have been at work in any event. But the reality of Germany's existence largely determined the nature and sequence of affairs as they appeared to march inexorably toward disaster. -

Final Report NATO Research Fellowship Prof. Dr. Holger H

Final Report NATO Research Fellowship Prof. Dr. Holger H. Herwig The University of Calgary Aggression Contained? The Federal Republic of Germany and International Security1 Two years ago, when I first proposed this topic, I had some trepidation about its relevance to current NATO policy. Forty-eight months of work on the topic and the rush of events especially in Central and East Europe since that time have convinced me both of its timeliness and of its relevance. Germany's role in SFOR in Bosnia since 1996, the very positive deployment of the German Army (Bundeswehr) in flood-relief work along the Oder River on the German- Polish border in the summer of 1997, and even the most recent revelations of neo-Nazi activity within the ranks of the Bundeswehr, have served only to whet my appetite for the project. For, I remain convinced that the German armed forces, more than any other, can be understood only in terms of Germany's recent past and the special military culture out of which the Bundeswehr was forged. Introduction The original proposal began with a scenario that had taken place in Paris in 1994. On that 14 July, the day that France annually sets aside as a national holiday to mark its 1789 Revolution, 189 German soldiers of the 294th Tank-Grenadier Battalion along with their twenty- four iron-crossed armoured personnel carriers for the first time since 1940 had marched down the Champs-Elysées in Paris. General Helmut Willmann's men had stepped out not to the tune of "Deutschland, 1 The research for this report was made possible by a NATO Research Fellowship. -

An Analysis of the Effect of Civil-Military Relations in the Third Reich on the Conduct of the German Campaign in the West in 1940

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 6-1-1964 An analysis of the effect of civil-military relations in the Third Reich on the conduct of the German campaign in the West in 1940 John Ogden Shoemaker University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Shoemaker, John Ogden, "An analysis of the effect of civil-military relations in the Third Reich on the conduct of the German campaign in the West in 1940" (1964). Student Work. 374. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/374 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF THE EFFECT OF CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN THE THIRD REICH ON THE CONDUCT OF THE GERMAN CAMPAIGN IN THE WEST IN 1940 by John Ogden Shoemaker A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the Department of History University of Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts June 1964 UMI Number: EP73012 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. DissertationPublishing UMI EP73012 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

Admiral Canaris of the Abwehr and WWII Spies in Lisbon by N.L

Admiral Canaris of the Abwehr and WWII Spies in Lisbon by N.L. Taylor German Spy Rings MI5, MI6, SOE are common household names for most English speakers, especially for fans of John Le Carré, the mastermind of spy stories and a member of the Intelligence and Counter-Intelligence clique himself. The British spy network during WWII has indeed been much-documented in newsreels, books, and spy films. On the other hand, the German spy network in Britain was limited, despite certain Nazi sympathies in high places during the War. Spying on the British, on home-ground, was directed from the German Legations in Dublin, Lisbon, and Oslo as well as from Hamburg. The number of German agents in Britain itself was small, their information unreliable and most of their communications were under strict surveillance. It was Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, the diminutive Head of the Abwehr, the German Intelligence Service, who had hand-picked six European capitals for developing the German spy-ring: Madrid, Lisbon, Berne, Ankara, Oslo, and Budapest. He felt that these were worth building up as a long-term investment, because it seemed unlikely that any of these cities would be occupied by either the Germans or the Allies and that, consequently, the diplomatic bags would continue to fly, officials would continue to come and businessmen continue to go. He added to their number the Vatican, which had its own sovereign status, its own ciphers, and its own representatives all over the world. Brussels, Warsaw, Sofia, Bucharest, the Hague, and Paris were mere short-term options, which he knew would be isolated when Germany declared war.1 Admiral Wilhelm Canaris Before the War began, the Abwehr had built a wide range of contacts worldwide.