History Extension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction After Totalitarianism – Stalinism and Nazism Compared

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89796-9 - Beyond Totalitarianism: Stalinism and Nazism Compared Michael Geyer and Sheila Fitzpatrick Excerpt More information 1 Introduction After Totalitarianism – Stalinism and Nazism Compared Michael Geyer with assistance from Sheila Fitzpatrick The idea of comparing Nazi Germany with the Soviet Union under Stalin is not a novel one. Notwithstanding some impressive efforts of late, however, the endeavor has achieved only limited success.1 Where comparisons have been made, the two histories seem to pass each other like trains in the night. That is, while there is some sense that they cross paths and, hence, share a time and place – if, indeed, it is not argued that they mimic each other in a deleterious war2 – little else seems to fit. And this is quite apart from those approaches which, on principle, deny any similarity because they consider Nazism and Stalinism to be at opposite ends of the political spectrum. Yet, despite the very real difficulties inherent in comparing the two regimes and an irreducible political resistance against such comparison, attempts to establish their commonalities have never ceased – not least as a result of the inclination to place both regimes in opposition to Western, “liberal” traditions. More often than not, comparison of Stalinism and Nazism worked by way of implicating a third party – the United States.3 Whatever the differences between them, they appeared small in comparison with the chasm that separated them from liberal-constitutional states and free societies. Since a three-way comparison 1 Alan Bullock, Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives (London: HarperCollins, 1991); Ian Kershaw and Moshe Lewin, eds., Stalinism and Nazism: Dictatorships in Comparison (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977); Henry Rousso, ed., Stalinisme et nazisme: Histoire et memoire´ comparees´ (Paris: Editions´ Complexe, 1999); English translation by Lucy Golvan et al., Stalinism and Nazism (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004); Richard J. -

DISCUSSION the Goldhagen Controversy

DISCUSSION The Goldhagen Controversy: Agonizing Problems, Scholarly Failure and the Downloaded from Political Dimension’ Hans-Ulrich Wehler (BieZefeZd) http://gh.oxfordjournals.org/ When a contentious book with a provoca1.ive message has aroused lively, not to say passionate, controversy, it is desirable that any new contribution to the debate should strive to provide as sober and clear a cost-benefit analysis as possible. It is best, moreover, to attend first to the book’s merits and achieve- ments, before giving an equal airing to its faults and limitations. In the case of Daniel Goldhagen’s Hiller’s Willing Executioners such a procedure is parti- cularly advisable, since the response in the American and German media to at Serials Department on February 18, 2015 this six-hundred-page study of ‘ordinary Germans and the Holocaust’ has not only been rather speedier than that of the academic world-though scholarly authorities have also, uncharacteristically, been quick off the mark-but has impaired the debate by promptly giving respectability to a number of stereo- types and misconceptions. The enthusiastic welcome that the book has received from journalists and opinion-formers in America is a problem in its own right, and we shall return to it later. But here in Germany there is no cause for complacency either, since the reaction in the public media has been far from satisfactory. With dismaying rapidity, and with a spectacular self-confidence that has frequently masked an ignorance of the facts, a counter-consensus has emerged. The book, we are repeatedly told, contains no new empirical data, since everything of significance on the subject has long been known; nor does it raise any stimulating new questions. -

Conservative Parties and the Birth of Democracy

Conservative Parties and the Birth of Democracy How do democracies form and what makes them die? Daniel Ziblatt revisits this timely and classic question in a wide-ranging historical narrative that traces the evolution of modern political democracy in Europe from its modest beginnings in 1830s Britain to Adolf Hitler’s 1933 seizure of power in Weimar Germany. Based on rich historical and quantitative evidence, the book offers a major reinterpretation of European history and the question of how stable political democracy is achieved. The barriers to inclusive political rule, Ziblatt finds, were not inevitably overcome by unstoppable tides of socioeconomic change, a simple triumph of a growing middle class, or even by working class collective action. Instead, political democracy’s fate surprisingly hinged on how conservative political parties – the historical defenders of power, wealth, and privilege – recast themselves and coped with the rise of their own radical right. With striking modern parallels, the book has vital implications for today’s new and old democracies under siege. Daniel Ziblatt is Professor of Government at Harvard University where he is also a resident fellow of the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies. He is also currently Fernand Braudel Senior Fellow at the European University Institute. His first book, Structuring the State: The Formation of Italy and Germany and the Puzzle of Federalism (2006) received several prizes from the American Political Science Association. He has written extensively on the emergence of democracy in European political history, publishing in journals such as American Political Science Review, Journal of Economic History, and World Politics. -

When Die Zeit Published Its Review of Decision Before Dawn

At the Front: common traitors in West German war films of the 1950s Article Accepted Version Wölfel, U. (2015) At the Front: common traitors in West German war films of the 1950s. Modern Language Review, 110 (3). pp. 739-758. ISSN 0026-7937 doi: https://doi.org/10.5699/modelangrevi.110.3.0739 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/40673/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5699/modelangrevi.110.3.0739 Publisher: Modern Humanities Research Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online AT THE FRONT: COMMON TRAITORS IN WEST GERMAN WAR FILMS OF THE 1950s Erst im militärischen Geheimnis kommt das Staatsgeheimnis zu sich selbst; da der Krieg als permanenter und totaler Zustand vorausgesetzt wird, läßt sich jeder beliebige Sachverhalt unter militärische Kategorien subsumieren: dem Feind gegenüber hat alles als Geheimnis und jeder Bürger als potentieller Verräter zu gelten. (HANS MAGNUS ENZENSBERGER) Die alten Krieger denken immer an die Kameraden, die gefallen sind, und meinen, ein Deserteur sei einer, der sie verraten hat. (LUDWIG BAUMANN) Introduction Margret Boveri, in the second volume of her treatise on Treason in the 20th Century, notes with respect to German resistance against National Socialism that the line between ethically justified and unethical treason is not easily drawn.1 She cites the case of General Hans Oster, deputy head of the Abwehr under Admiral Canaris. -

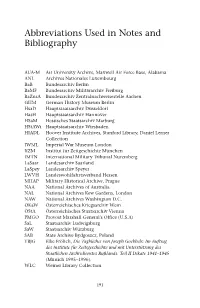

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

The Abwehr : from German Espionage Agency, to Centre of Resistance Against Hitler Student: Greg Elder Sponsor: Dr

The Abwehr : From German espionage agency, to centre of resistance against Hitler Student: Greg Elder Sponsor: Dr. Vasilis Vourkoutiotis The Project: About the Abwehr: My research for Dr. Vourkoutiotis has mainly involved searching the microfilmed finding-aids for the German The name “Abwehr” in German can be translated literally as Captured Records archive located in Washington, D.C. The task requires me to scan the microfilmed data sheets “defence.” However, despite its name, the Abwehr became one of for information relevant to the project, and then summarize that info for the Professor. The process has greatly the forefront intelligence gathering establishments in Nazi Germany. familiarized me with the everyday work of a professional historian, and some of the necessary research steps for The organization was tasked with gathering information on the a historical monograph. The project has also furthered my knowledge of German history, especially regarding country’s enemies, primarily using field-based agents. The Abwehr the different espionage organizations at work during World War II. fell under the administration of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Supreme Command of the Armed Forces) and interacted heavily This work is in preparation for Dr. Vourkoutiotis’s eventual trip to the archives in Washington D.C. where he will with other German espionage agencies such as the locate the important documents relating to the Abwehr. The research completed by myself in Ottawa will enable Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service of the SS and Nazi Party). him to visit the archives already aware of what relevant documents exist, and where to begin in his search for primary sources. -

Totalitarianism 1 Totalitarianism

Totalitarianism 1 Totalitarianism Totalitarianism (or totalitarian rule) is a political system where the state holds total authority over the society and seeks to control all aspects of public and private life wherever necessary.[1] The concept of totalitarianism was first developed in a positive sense in the 1920's by the Italian fascists. The concept became prominent in Western anti-communist political discourse during the Cold War era in order to highlight perceived similarities between Nazi Germany and other fascist regimes on the one hand, and Soviet communism on the other.[2][3][4][5][6] Aside from fascist and Stalinist movements, there have been other movements that are totalitarian. The leader of the historic Spanish reactionary conservative movement called the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right declared his intention to "give Spain a true unity, a new spirit, a totalitarian polity..." and went on to say "Democracy is not an end but a means to the conquest of the new state. Moloch of Totalitarianism – memorial of victims of repressions exercised by totalitarian regimes, When the time comes, either parliament submits or we will eliminate at Levashovo, Saint Petersburg. it."[7] Etymology The notion of "totalitarianism" a "total" political power by state was formulated in 1923 by Giovanni Amendola who described Italian Fascism as a system fundamentally different from conventional dictatorships.[8] The term was later assigned a positive meaning in the writings of Giovanni Gentile, Italy’s most prominent philosopher and leading theorist of fascism. He used the term “totalitario” to refer to the structure and goals of the new state. -

The Origins of Chancellor Democracy and the Transformation of the German Democratic Paradigm

01-Mommsen 7/24/07 4:38 PM Page 7 The Origins of Chancellor Democracy and the Transformation of the German Democratic Paradigm Hans Mommsen History, Ruhr University Bochum The main focus of the articles presented in this special issue is the international dimension of post World War II German politics and the specific role filled by the first West German chancellor, Konrad Adenauer. Adenauer’s main goal was the integration of the emerg- ing West German state into the West European community, while the reunification of Germany was postponed. In his view, any restoration of the former German Reich depended upon the cre- ation of a stable democratic order in West Germany. Undoubtedly, Adenauer contributed in many respects to the unexpectedly rapid rise of West Germany towards a stable parliamentary democratic system—even if most of the credit must go to the Western Allies who had introduced democratic structures first on the state level, and later on paved the way to the establishment of the Federal Republic with the fusion of the Western zones and the installment of the Economic Council in 1948. Besides the “economic miracle,” a fundamental shift within the West German political culture occurred, which gradually overcame the mentalities and prejudices of the late Weimar years that had been reactivated during the immediate aftermath of the war. While the concept of a specific “German path” (Sonderweg) had been more or less eroded under the impact of the defeat of the Nazi regime, the inherited apprehensiveness toward Western political traditions, symptomatic of the constitutional concepts of the German bourgeois resistance against Hitler, began to be replaced by an increasingly German Politics and Society, Issue 82 Vol. -

Responsibility for Future Generations (PDF)

THE POLITICAL RESPONSIBILITY OF THE CHURCH Responsibility for Future Generations PRIMING THE PUMP: When you think about the future the children of St. Andrew face, what fills you with foreboding? INTRODUCTION: “AFTER TEN YEARS” 1 1. Written at Christmas 1942, a few months prior to arrest on April 5, 1943 2. Addressed to co-conspirators a. Eberhard Bethge: student, confessing partner, and dear friend b. Hans von Dohnanyi: brother-in-law and mastermind of conspiracy c. Hans Oster: chief of Central Section in Military Intelligence Office 3. Included as Prologue in Letters and Papers from Prison a. Bridges gap between final months of freedom and imprisonment b. “New Year’s” reflection, taking stock of events of events and issues EXPOSING THE MASQUERADE OF EVIL 1. Nazis clothed themselves in “garb of relative historical and social justice” 2 2. In extreme situation like Nazi Germany may have to stand firm with truthful/responsible deeds rather than words 3. Failed attempts to stand firm a. Reasonable people: reason will fix things b. Fanatical people: attack evil with purity of principle c. People of conscience: torn apart by conflicting ethical factors d. Dutiful people: obey commands of those in authority e. People of freedom: value necessary deed more highly than untarnished conscience and reputation f. Privately virtuous: close eyes to injustices around them 4. Standing firm by engaging in responsible/truthful action a. Ultimate not reason, principles, conscience, duty, freedom, virtue b. Obedient and responsible action toward God and other humans c. Critiques any approach focused too exclusively on consequences, motives, or any one ethical factor d. -

Kirchubel on Citino, 'The Wehrmacht's Last Stand: the German Campaigns of 1944-1945'

H-War Kirchubel on Citino, 'The Wehrmacht's Last Stand: The German Campaigns of 1944-1945' Review published on Saturday, May 5, 2018 Robert M. Citino. The Wehrmacht's Last Stand: The German Campaigns of 1944-1945. Modern War Studies Series. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2017. Illustrations, maps. 632 pp. $34.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-7006-2494-2. Reviewed by Robert Kirchubel (Purdue University)Published on H-War (May, 2018) Commissioned by Margaret Sankey (Air War College) Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=51318 Robert M. Citino, presently at the National WWII Museum, has again teamed up with the University Press of Kansas for his latest installment on modern German military history. The Wehrmacht’s Last Stand investigates Germany’s final battles against the Soviet Union and the Western Allies to its east, south, and west. As we have come to expect from Citino, the book is thoroughly researched, clearly narrated, and tightly argued. While Wehrmacht’s Last Stand synthesizes a great number of secondary materials—a review of its bibliography reveals only a couple pre-1945 German military journals that could be considered primary sources—it is full of new insights and thought-provoking interpretations of key events in late World War II.[1] Citino takes military historians to school by demonstrating how operational history should be written, at a time when elements of the academy consider that subdiscipline passé and of doubtful utility. The Wehrmacht had a good run during the first two years of the war, then a couple years of transition (notably against the USSR), but in Wehrmacht’s Last Stand it is reeling backward on every front. -

Religious and Secular Responses to Nazism: Coordinated and Singular Acts of Opposition

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition Kathryn Sullivan University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Sullivan, Kathryn, "Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 891. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/891 RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR RESPONSES TO NAZISM COORDINATED AND SINGULAR ACTS OF OPPOSITION by KATHRYN M. SULLIVAN B.A. University of Central Florida, 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2006 © 2006 Kathryn M. Sullivan ii ABSTRACT My intention in conducting this research is to satisfy the requirements of earning a Master of Art degree in the Department of History at the University of Central Florida. My research aim has been to examine literature written from the 1930’s through 2006 which chronicles the lives of Jewish and Gentile German men, women, and children living under Nazism during the years 1933-1945. -

Mommsen, Hans, Germans Against Hitler

GERMANS AGAINST HITLER HANS MOMMSEN GERMANSGERMANSGERMANS AGAINSTAGAINST HITLERHITLER THE STAUFFENBERG PLOT AND RESISTANCE UNDER THE THIRD REICH Translated and annotated by Angus McGeoch Introduction by Jeremy Noakes New paperback edition published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com First published in hardback in 2003 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd as Alternatives to Hitler. Originally published in 2000 as Alternative zu Hitler – Studien zur Geschichte des deutschen Widerstandes. Copyright © Verlag C.H. Beck oHG, Munchen, 2000 Translation copyright © I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd, 2003, 2009 The translation of this work has been supported by Inter Nationes, Bonn. The right of Hans Mommsen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 978 1 84511 852 5 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library Project management by Steve Tribe, Andover Printed and bound in India by Thomson Press India Ltd ContentsContentsContents Preface by Hans Mommsen vii Introduction by Jeremy Noakes 1 1. Carl von Ossietzky and the concept of a right to resist in Germany 9 2. German society and resistance to Hitler 23 3.