Admiral Canaris of the Abwehr and WWII Spies in Lisbon by N.L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

Title: Daring Missions of World War II Author: William B. Breuer ISBN: 0-471-40419-5 Introduction World war ii, the mightiest endeavor that history has known, was fought in many arenas other than by direct confrontation between opposing forces. One of the most significant of these extra dimensions was a secret war-within-a-war that raged behind enemy lines, a term that refers to actions taken a short dis- tance to the rear of an adversary’s battlefield positions or as far removed as a foe’s capital or major headquarters. Relentlessly, both sides sought to penetrate each other’s domain to dig out intelligence, plant rumors, gain a tactical advantage, spread propaganda, create confusion, or inflict mayhem. Many ingenious techniques were employed to infiltrate an antagonist’s territory, including a platoon of German troops dressed as women refugees and pushing baby carriages filled with weapons to spearhead the invasion of Belgium. Germans also wore Dutch uniforms to invade Holland. The Nazi attack against Poland was preceded by German soldiers dressed as civilians and by others wearing Polish uniforms. In North Africa, British sol- diers masqueraded as Germans to strike at enemy airfields, and both sides dressed as Arabs on occasion. One British officer in Italy disguised himself as an Italian colonel to get inside a major German headquarters and steal vital information. In the Pacific, an American sergeant of Japanese descent put on a Japan- ese officer’s uniform, sneaked behind opposing lines, and brought back thir- teen enemy soldiers who had obeyed his order to lay down their weapons. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Dokumentation Das Letzte Duell. Die

Dokumentation Horst Mühleisen Das letzte Duell. Die Auseinandersetzungen zwischen Heydrich und Canaris wegen der Revision der »Zehn Gebote« I. Die Bedeutung der Dokumente Admiral Wilhelm Franz Canaris war als Chef der Abwehr eine der Schlüsselfigu- ren des Zweiten Weltkrieges. Rätselhaftes umgibt noch heute, mehr als fünfzig Jah- re nach seinem gewaltsamen Ende, diesen Mann. Für Erwin Lahousen, einen sei- ner engsten Mitarbeiter, war Canaris »eine Person des reinen Intellekts«1. Die Qua- lifikationsberichte über den Fähnrich z.S. im Jahre 1907 bis zum Kapitän z.S. im Jahre 1934 bestätigen dieses Urteü2. Viele Biographen versuchten, dieses abenteu- erliche und schillernde Leben zu beschreiben; nur wenigen ist es gelungen3. Un- 1 Vgl. die Aussage des Generalmajors a.D. Lahousen Edler von Vivremont (1897-1955), Dezember 1938 bis 31.7.1943 Chef der Abwehr-Abteilung II, über Canaris' Charakter am 30.11.1945, in: Der Prozeß gegen die Hauptkriegsverbrecher vor dem Internationalen Mi- litärgerichtshof (International Military Tribunal), Nürnberg, 14.11.1945-1.10.1946 (IMT), Bd 2, Nürnberg 1947, S. 489. Ders., Erinnerungsfragmente von Generalmajor a.D. Erwin Lahousen über das Amt Ausland/Abwehr (Canaris), abgeschlossen am 6.4.1948, in: Bun- desarchiv-Militärarchiv (BA-MA) Freiburg, MSg 1/2812, S. 64. Vgl. auch Ernst von Weiz- säcker, Erinnerungen, München, Leipzig, Freiburg i.Br. 1952, S. 175. 2 Vgl. Personalakte Wilhelm Canaris, in: BA-MA, Pers 6/105, fol. 1Γ-105Γ, teilweise ediert von Helmut Krausnick, Aus den Personalakten von Canaris, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (VfZG), 10 (1962), S. 280-310. Eine weitere Personalakte, eine Nebenakte, in: BA-MA, Pers 6/2293. -

A Counterintelligence Reader, Volume 2 Chapter 1, CI in World

CI in World War II 113 CHAPTER 1 Counterintelligence In World War II Introduction President Franklin Roosevelts confidential directive, issued on 26 June 1939, established lines of responsibility for domestic counterintelligence, but failed to clearly define areas of accountability for overseas counterintelligence operations" The pressing need for a decision in this field grew more evident in the early months of 1940" This resulted in consultations between the President, FBI Director J" Edgar Hoover, Director of Army Intelligence Sherman Miles, Director of Naval Intelligence Rear Admiral W"S" Anderson, and Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A" Berle" Following these discussions, Berle issued a report, which expressed the Presidents wish that the FBI assume the responsibility for foreign intelligence matters in the Western Hemisphere, with the existing military and naval intelligence branches covering the rest of the world as the necessity arose" With this decision of authority, the three agencies worked out the details of an agreement, which, roughly, charged the Navy with the responsibility for intelligence coverage in the Pacific" The Army was entrusted with the coverage in Europe, Africa, and the Canal Zone" The FBI was given the responsibility for the Western Hemisphere, including Canada and Central and South America, except Panama" The meetings in this formative period led to a proposal for the organization within the FBI of a Special Intelligence Service (SIS) for overseas operations" Agreement was reached that the SIS would act -

Full List of Files Released L C P First Date Last Date Scope/Content

Full list of files released L C P First Date Last Date Scope/Content Former Ref Note KV 2 WORLD WAR II KV 2 German Intelligence Agents and Suspected Agents KV 2 3386 06/03/1935 18/08/1953 Greta Lydia OSWALD: Swiss. Imprisoned in PF 45034 France on grounds of spying for Germany in 1935, OSWALD was said to be working for the Gestapo in 1941 KV 2 3387 12/11/1929 12/01/1939 Oscar Vladimirovich GILINSKY alias PF 46098 JILINSKY, GILINTSIS: Latvian. An arms dealer VOL 1 in Paris, in 1937 GILINSKY was purchasing arms for the Spanish Popular Front on behalf of the Soviet Government. In November 1940 he was arrested by the Germans in Paris but managed to obtain an exit permit. He claimed he achieved this by bribing individual Germans but, after ISOS material showed he was regarded as an Abwehr agent, he was removed in Trinidad from a ship bound for Buenos Aires and brought to Camp 020 for interrogation. He was deported in 1946 KV 2 3388 13/01/1939 16/02/1942 Oscar Vladimirovich GILINSKY alias PF 46098 JILINSKY, GILINTSIS: Latvian. An arms dealer VOL 2 in Paris, in 1937 GILINSKY was purchasing arms for the Spanish Popular Front on behalf of the Soviet Government. In November 1940 he was arrested by the Germans in Paris but managed to obtain an exit permit. He claimed he achieved this by bribing individual Germans but, after ISOS material showed he was regarded as an Abwehr agent, he was removed in Trinidad from a ship bound for Buenos Aires and brought to Camp 020 for interrogation. -

When Die Zeit Published Its Review of Decision Before Dawn

At the Front: common traitors in West German war films of the 1950s Article Accepted Version Wölfel, U. (2015) At the Front: common traitors in West German war films of the 1950s. Modern Language Review, 110 (3). pp. 739-758. ISSN 0026-7937 doi: https://doi.org/10.5699/modelangrevi.110.3.0739 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/40673/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5699/modelangrevi.110.3.0739 Publisher: Modern Humanities Research Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online AT THE FRONT: COMMON TRAITORS IN WEST GERMAN WAR FILMS OF THE 1950s Erst im militärischen Geheimnis kommt das Staatsgeheimnis zu sich selbst; da der Krieg als permanenter und totaler Zustand vorausgesetzt wird, läßt sich jeder beliebige Sachverhalt unter militärische Kategorien subsumieren: dem Feind gegenüber hat alles als Geheimnis und jeder Bürger als potentieller Verräter zu gelten. (HANS MAGNUS ENZENSBERGER) Die alten Krieger denken immer an die Kameraden, die gefallen sind, und meinen, ein Deserteur sei einer, der sie verraten hat. (LUDWIG BAUMANN) Introduction Margret Boveri, in the second volume of her treatise on Treason in the 20th Century, notes with respect to German resistance against National Socialism that the line between ethically justified and unethical treason is not easily drawn.1 She cites the case of General Hans Oster, deputy head of the Abwehr under Admiral Canaris. -

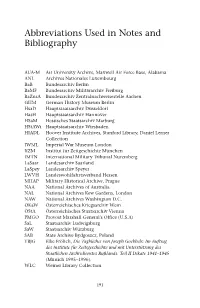

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

The Round Tablette October 2006

The Round Tablette November 2006 Volume 15 Number 3 Published by WW II History Roundtable a glowing report to his government after Edited by Jim Gerber meeting Oshima, the designated military attaché to Germany, in March 1934. Colonel Welcome to the November meeting of Oshima “belongs to the inner circle of the Dr. Harold C. Deutsch World War Two Japan’s military…and therefore is very well History Roundtable. As is our usual practice, informed about everything connected with tonight is the annual Dr. Deutsch lecture. the militarists and their plans for the Tonight’ guest speaker is author Carl Boyd. future.” Oshima arrived in Berlin in May His topic is: The Relations Between Nazi 1934 to take up his post. Germany and Imperial Japan. Oshima initially started working with The following overview is taken from Wilhelm Canaris, head of the German material provided by Mr. Boyd. central military intelligence service, but soon exceeded his military orders by becoming Relations Between Nazi Germany and secretly engaged in political discussions Imperial Japan. leading to the highest levels in the German government. These discussions included What could possibly enable such two Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s personal decidedly different societies as Japan and ambassador at large, in the spring of 1935, Germany to come together in an axis alliance and Hitler himself in the autumn of 1935, by and fight on the same side during the Second which point Oshima was a major general. World War? They were, after all, on opposite sides of the globe; furthermore, they The growing military climate in were separated by racial differences, major Japan was eroding the influence of civilian religious differences, vast cultural forces in government. -

Critical Analysis of German Operational Intelligence Part II

UNCLASSIFIED Critical Analysis of German Operational Intelligence Part II Sources of Intelligence work, and many German field orders stress the impor tance of the capture, preservation, and quick evalua The study of sources and types of intelligence tion of enemy documents; but they paid scant atten available to the Germans shows clearly how the inher tion to adequate training of personnel, and no ent weaknesses· of their intelligence system extended outstanding work seems to have been done. During the to their detailed work. The insufficient importance second half of the war, the amount of captured they attributed to intelligence meant that all its documents in German hands decreased, owing to the branches suffered from shortage of personnel and nature of their defensive warfare, and the opportunity equipment; and, although in some fields there was an for good document work became fewer. approach to German thoroughness, in the main the That the Germans were capable of good detailed lack of attention to detail was surprising. work is shown by their practice in the Internment The interrogation of prisoners of war, which they Center for Captured Air Force Personnel at Oberursel, regarded as one of their most fruitful sources of where all Allied air crews were first interrogated. The information, is a good example. In the beginning of German specialists here realized the value of combined the war, their need for detailed and comprehensive document and interrogation work, and devised an interrogation was small; but even later, a standard excellent system of analysis. In order to identify the OKH questionnaire was still being used and at no time units of their prisoners - a matter of the highest was much initiative shown on the part of interrogators. -

The Abwehr : from German Espionage Agency, to Centre of Resistance Against Hitler Student: Greg Elder Sponsor: Dr

The Abwehr : From German espionage agency, to centre of resistance against Hitler Student: Greg Elder Sponsor: Dr. Vasilis Vourkoutiotis The Project: About the Abwehr: My research for Dr. Vourkoutiotis has mainly involved searching the microfilmed finding-aids for the German The name “Abwehr” in German can be translated literally as Captured Records archive located in Washington, D.C. The task requires me to scan the microfilmed data sheets “defence.” However, despite its name, the Abwehr became one of for information relevant to the project, and then summarize that info for the Professor. The process has greatly the forefront intelligence gathering establishments in Nazi Germany. familiarized me with the everyday work of a professional historian, and some of the necessary research steps for The organization was tasked with gathering information on the a historical monograph. The project has also furthered my knowledge of German history, especially regarding country’s enemies, primarily using field-based agents. The Abwehr the different espionage organizations at work during World War II. fell under the administration of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Supreme Command of the Armed Forces) and interacted heavily This work is in preparation for Dr. Vourkoutiotis’s eventual trip to the archives in Washington D.C. where he will with other German espionage agencies such as the locate the important documents relating to the Abwehr. The research completed by myself in Ottawa will enable Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service of the SS and Nazi Party). him to visit the archives already aware of what relevant documents exist, and where to begin in his search for primary sources. -

Transkribierte Fassung

Die Seelen der Gerechten sind in Gottes Hand und des Todes Qual berührt sie nicht. Den Augen der Toren schienen sie zu sterben. Als Unglück wurde ihr Ende angesehen, ihr Scheiden von uns als Untergang: Sie aber sind in Frieden. Wenn sie auch bei den Menschen Qualen erlitten, so ist doch ihre Hoffnung voll der Unsterblichkeit. Ein wenig nur wurden sie gepeinigt, aber viel Herrliches wird ihnen widerfahren. Denn Gott hat sie geprüft und er fand sie seiner wert. Wie Gold im Ofen hat er sie geprüft und wie ein Brandopfer sie angenommen. Zu seiner Zeit wird man nach ihnen schauen. Sie werden die Völker richten und über die Nationen herrschen und der Herr wird ihr König sein in Ewigkeit. (Buch der Weisheit Salomonis 3, 1–8) † Nach Gottes heiligem Willen und in der Kraft ihres Glaubens starben den Heldentod im freien, ehrenvolle Kampfe für Wahrheit und Recht, für des Deutschen Volkes Freiheit, für der Deutschen Waffen Reinheit und Ehre, als bewußte Sühne für das vor Gott verübte Unrecht unseres Volkes die Führer der aktiven Widerstands-Bewegung des 20. Juli 1944: Ludwig Beck, Generaloberst, erschossen 20. Juli 1944 Dr. Karl Goerdeler, vorm. Oberbürgerm., erhängt 1. Febr. 1945 Graf Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg, Oberst i. G., erschossen 20. Juli 1944 Erwin v. Witzleben, Generalfeldmarschall, erhängt 8. Aug. 1944 – zusammen mit zahlreichen Kameraden aus der Armee und aus allen Stämmen, Ständen und Parteien des Deutschen Volkes – namentlich: ╬ Robert Bernardis, Oberstleutnant † 8. Aug. 1944 Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff, Botschaftsrat † 23. April 1945 Hans-Jürgen Graf v. Blumenthal, Major i. G. † 13. Okt. 1944 Hasso von Boehmer, Oberstleutnant i. -

Die Canaris-Tagebücher - Legenden Und Wirklichkeit

Dokumentation Horst Mühleisen Die Canaris-Tagebücher - Legenden und Wirklichkeit Kein Historiker hat sie je gesehen. Forscher, Journalisten und Staatsanwälte suchten sie nach dem Ende der nationalsozialistischen Herrschaft vergebens: die verschol- lenen Tagebücher des Admirals Wilhelm Canaris (1887-1945), für nicht wenige der Fahnder »eine ungeheuere historische Quelle«1, die Auskünfte über die Natur die- ses außergewöhnlichen, von Geheimnissen und Rätseln umgebenen Mannes hätten geben können, der einst als Chef des Amtes Ausland/Abwehr von November 1939 bis Februar 1944 Beschützer des konservativen Widerstandes gewesen war. Das Schicksal der Canaris-Papiere beschäftigt die historische Forschung, seit ein SS-Standgericht im Konzentrationslager Flossenbürg den ehemaligen Abwehr- chef am 8. April 1945 wegen angeblichen Hochverrats zum Tode verurteilte und ihn in den frühen Morgenstunden des folgenden Tages erhängen ließ. Mit dem Ende von Canaris verlor sich auch die Spur seiner geheimen Tagebücher und Reise- berichte, die Walter Huppenkothen, Ankläger von Canaris im Prozess, führender Funktionär der Geheimen Staatspolizei, restlos verbrannt hat, wenn man seine Aussagen glauben will. Einige, meist Canaris' Getreue der einstigen Abwehr, taten es nicht. Sie glaubten hartnäckig daran, dass ihr listiger Chef doch Wege gefunden hatte, eine bis dahin unbekannte Kopie seiner Tagebücher an einem entlegenen Ort in Sicherheit zu bringen; und das rasch aufkommende Gerücht, die Geheime Staatspolizei habe keineswegs alle Canaris-Papiere verbrannt, bestärkte