Dirven Palmyrenes in Hatra S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

EASO Rapport D'information Sur Les Pays D'origine Iraq Individus Pris

European Asylum Support Office EASO Rapport d’information sur les pays d’origine Iraq Individus pris pour cible Mars 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Rapport d’information sur les pays d’origine Iraq Individus pris pour cible Mars 2019 D’autres informations sur l’Union européenne sont disponibles sur l’internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-051-5 doi: 10.2847/95098 © European Asylum Support Office 2019 Sauf indication contraire, la reproduction est autorisée, moyennant mention de la source. Pour les contenus reproduits dans la présente publication et appartenant à des tierces parties, se référer aux mentions relatives aux droits d’auteur desdites tierces parties. Photo de couverture: © Joel Carillet, un drapeau iraquien flotte sur le toit de l’église syro- orthodoxe Saint-Ephrem de Mossoul (Iraq), qui a été fortement endommagée, quelques mois après que ce quartier de Mossoul a été repris à l’EIIL. L’emblème de l’EIIL était peint sur la façade du bâtiment durant l’occupation de Mossoul par l’EIIL. EASO RAPPORT D’INFORMATION SUR LES PAYS D’ORIGINE IRAQ: INDIVIDUS PRIS POUR CIBLE — 3 Remerciements Le présent rapport a été rédigé par des experts du centre de recherche et de documentation (Cedoca) du bureau belge du Commissariat général aux réfugiés et aux apatrides. Par ailleurs, les services nationaux d’asile et de migration suivants ont procédé à une relecture du présent rapport, en concertation avec l’EASO: Pays-Bas, Bureau des informations sur les pays et de l’analyse linguistique, ministère de la justice Danemark, service danois de l’immigration La révision apportée par les départements, experts ou organisations susmentionnés contribue à la qualité globale du rapport, mais ne suppose pas nécessairement leur approbation formelle du rapport final, qui relève pleinement de la responsabilité de l’EASO. -

IDP and Refugee Camp Locations - As of January 2017

For Humanitarian Purposes Only IRAQ Production date: 01 February 2017 IDP and Refugee Camp Locations - As of January 2017 Za k ho T U R K E Y Darkar ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑⛳⚑Bersive II Chamishku Bersive I Dawudiya ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Am e di Bajet Kandala ² Rwanga Dahuk Community Me r ga s ur Da h uk Su m el So r an !PDahuk Kabrato I+II Ak r e Khanke ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Shariya S Y R I A ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Sh i kh a n Domiz I+II Essian Akre ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Sheikhan Amalla ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Garmawa ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑Mamrashan ⛳⚑ Mamilian ⛳⚑Nargizlia Ch o ma n 1 + 2 Tel af ar Ti lk a if Qaymawa ⛳⚑ Basirma ⛳⚑ Bardarash Darashakran ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Sh a ql a w a Si n ja r Hasansham M2 Gawilan Kawergosk Mosul!P ⛳⚑ I R A N Hasansham U3 ⛳⚑⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Baharka ⛳⚑ Ps h da r Ha m da n iy a Khazer M1 Ra n ia Harsham ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Erbil Ankawa 2 !P Erbil Mo s ul Ninewa Er b il Ko i sn j aq Qushtapa ⛳⚑ Do k an Debaga 1 ⛳⚑ Debaga 4 ⛳⚑⛳⚑ Surdesh Debaga Debaga 2 ⛳⚑ Stadium Ba 'a j Hasiyah ⛳⚑ Tina ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Qayyarah-Jad'ah Sh a rb a zh e r Pe n jw i n Ma k hm u r Ki r ku k Da b es Sulaymaniyah !P Barzinja Kirkuk ⛳⚑ Su l ay m an i y ah Ha t ra !P Arbat IDP ⛳⚑ Sh i rq a t ⛳⚑ Ashti IDP Nazrawa ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑Arbat Refugee Yahyawa ⛳⚑⛳⚑ Laylan 1 Sulaymaniyah Ha w ig a Kirkuk Da r ba n d ih k an Daquq ⛳⚑ Ch a mc h a ma l Laylan 2 ⛳⚑ Ha l ab j a Da q uq Ka l ar Hajjaj Camp ⛳⚑ Al-Alam ⛳⚑⛳⚑2 (MoMD) Ba i ji Al Alam 1 To oz (UNHCR) Tik r it Tazade ⛳⚑Al Safyh ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Tikrit Ru 'u a University Qoratu ⛳⚑ Al Obaidi Ki f ri ⛳⚑ Salah al-Din Da u r Ka 'i m Al Wand 1 Al Wand 2⛳⚑ Ha d it h a Sa m ar r a Al Abassia Al-Hawesh ⛳⚑ Kh a na q in ⛳⚑ !P Samarra Al-Iraq Al-Hardania Al-Muahad ⛳⚑ Diyala ⛳⚑ -

Social, Economic and Political Studies of the Middle East and Asia (S.E.P.S.M.E.A.)

SEPS-93-meouchy.qxd 10/20/2003 11:03 AM Page i THE BRITISH AND FRENCH MANDATES IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVES / LES MANDATS FRANÇAIS ET ANGLAIS DANS UNE PERSPECTIVE COMPARATIVE SEPS-93-meouchy.qxd 10/20/2003 11:03 AM Page ii SOCIAL, ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL STUDIES OF THE MIDDLE EAST AND ASIA (S.E.P.S.M.E.A.) (Founding editor: C.A.O. van Nieuwenhuijze) Editor REINHARD SCHULZE Advisory Board Dale Eickelman (Dartmouth College) Roger Owen (Harvard University) Judith Tucker (Georgetown University) Yann Richard (Sorbonne Nouvelle) VOLUME 93 SEPS-93-meouchy.qxd 10/20/2003 11:03 AM Page iii THE BRITISH AND FRENCH MANDATES IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVES / LES MANDATS FRANÇAIS ET ANGLAIS DANS UNE PERSPECTIVE COMPARATIVE EDITED BY / EDITÉ PAR NADINE MÉOUCHY and/et PETER SLUGLETT WITH/AVEC LA COLLABORATION AMICALE DE GÉRARD KHOURY and/et GEOFFREY SCHAD BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 SEPS-93-meouchy.qxd 10/20/2003 11:03 AM Page iv This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The British and French mandates in comparative perspectives / edited by Nadine Méouchy and Peter Sluglett ; with Gérard Khoury and Geoffrey Schad = Les mandats français et anglais dans une perspective comparative / édité par Nadine Méouchy et Peter Sluglett ; avec la collaboration amicale de Gérard Khoury et Geoffrey Schad. p. cm. — (Social, economic, and political studies of the Middle East and Asia, ISSN 1385-3376 ; v. 93) Proceedings of a conference held in Aix-en-Provence, June 2001. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 90-04-13313-5 (alk. paper) 1. -

A NOTE on SYRIA and the UNITED ARAB REPUBLIC by Alan W.Horton

NORTHEAST AFRICA SERIES Vol. M No. 1 (United Arab Republic) A NOTE ON SYRIA AND THE UNITED ARAB REPUBLIC by Alan W.Horton Reports This Report is one of a continuing series on current developments in world affairs written by Associates of the American Universities Field Staff. It is distributed to subscribers to the AUFS Reports Service as a useful addition to the American fund of information on for- eign affairs. ALAN W. HORTON has The writer is associated with the AUFS on a full-time since 1947 rcsidcd in the hlid- basis, spending long periods abroad and returning to dle East as a student. teacher, the United States periodically to lecture on the cam- relief workcr, and college ad- puses of AUFS sponsoring educational institutions. ministrator. He began the study of Arabic at the Ameri- Chosen for skill in collecting, reporting, and eval- can University at Cairo's uating data, each AUFS Associate combines long per- School of Oriental St~~diesin sonal observation with scholarly studies relating to October 1947. While continu- ing as a student he also taught political scicnce tllerc his area. the following year. For a time hc engaged in relicf Founded in 1951 as a nonprofit educational organi- \\-ork among the Arah refugees in connection with the zation, the AUFS at first limited distribution of the 1)rograrn of thc American Friends Service Committet, Reports to its corporate member colleges and univer- and later that of the UN Rclief and Works Agency. Before his appointment as Dean of the School of Ori- sities. Later, subscription categories were established ental Studies at AUC in 195.5, hlr. -

Ninewa Governorate Profile March 2009

Ninewa Governorate Profile March 2009 Overview Located in northern Iraq and bordering on Syria, Ninewa is Iraq’s third largest and second most populated governorate. The capital Mosul is Iraq’s third largest city. Sinjar, Telafar, Tilkaif, Al-Shikhan and Akre dis- tricts all have disputed boundaries with Dahuk. Al-Hamdaniya district has a disputed boundary with Erbil. Security worsened during the second half of 2008, with ethnic ten- sions leading to the displacement of 13,000 Christians from Mosul to surrounding areas. Although most of these families have returned and violence has decreased, the situation remains tense, particularly in Mosul city. Telafar, Sinjar, Al-Ba’aj and Hatra districts have among the worst rates of connection to the general water network in Iraq. All districts apart from Hatra have prolonged power cuts or are not connected to the general electricity network. Poverty is a significant problem in all districts except Al-Ba’aj. Demographics Governorate Capital: Mosul Area: 37,323 sq km (8.6% of Iraq) Population: 2,811,091 (9% of total) IDPs & Returnees Source: WFP VAM (2007) Number4156/2#78#*+,-#93:#./0123//-#;3#4;3/<9# of IDPs and Returnees per 1000 of Gender Distribution: Male: 50% Female: 50% Geographical Distribution: Rural: 39% Urban: 61% the population in Ninewa and Iraq Source: GoI COSIT (est. for 2007) Population by district: &'&!# ./0123//-# Al-Mosul 1,620,259 Telafar 382,050 "# Al-Hamdaniya 143,462 Al-Shikhan 49,396 Tilkaif 190,403 Al-Hatre 55,157 Sinjar 237,073 Al-Baaj 133,291 Source: WFP VAM (2007)* $%# -

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq As a Violation Of

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq as a Violation of Human Rights Submission for the United Nations Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights About us RASHID International e.V. is a worldwide network of archaeologists, cultural heritage experts and professionals dedicated to safeguarding and promoting the cultural heritage of Iraq. We are committed to de eloping the histor! and archaeology of ancient "esopotamian cultures, for we belie e that knowledge of the past is ke! to understanding the present and to building a prosperous future. "uch of Iraq#s heritage is in danger of being lost fore er. "ilitant groups are ra$ing mosques and churches, smashing artifacts, bulldozing archaeological sites and illegall! trafficking antiquities at a rate rarel! seen in histor!. Iraqi cultural heritage is suffering grie ous and in man! cases irre ersible harm. To pre ent this from happening, we collect and share information, research and expert knowledge, work to raise public awareness and both de elop and execute strategies to protect heritage sites and other cultural propert! through international cooperation, advocac! and technical assistance. R&SHID International e.). Postfach ++, Institute for &ncient Near -astern &rcheology Ludwig-Maximilians/Uni ersit! of "unich 0eschwister-Scholl/*lat$ + (/,1234 "unich 0erman! https566www.rashid-international.org [email protected] Copyright This document is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution .! International license. 8ou are free to copy and redistribute the material in an! medium or format, remix, transform, and build upon the material for an! purpose, e en commerciall!. R&SHI( International e.). cannot re oke these freedoms as long as !ou follow the license terms. -

Iraq- Ninewa Governorate, Hatra District

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Ninewa G( overnorate, Hatra Dis( t( rict ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ((( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( (( Um Izam (( Al A'dnaniyah collective Sibya Ain Salibi Tiniya Khuwaitala ( ( ( Khubairat Hay- Al Ulama’a ( Mughaiyar Tal Sawan IQ-P20237 Village Al Ebra - sector 1 Um Khaiya IQ-P19933 ( ( IQ-P20229 IQ-P20115 IQ-P20111 ( IQ-P20073 ( Tal Hayit IQ-P20660 IQ-P20817 IQ-P20879 Abu Hujaira Bakhaira IQ-P20901 IQ-P19729 IQ-P20895 ( Turkey ( ( Qamishiya ( Adaya IQ-P19921 ( ( ( (( IQ-P20668 ( Abu Shuwaiha IQ-P20011 Hay-Hefaa (( ( IQ-P20641 IQ-P19925 ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Abu Sanam Nizaza ( IQ-P19924 HAY- AL SIHA ! Al A'dnaniyah ( Mosul IQ!-P20085 HAY-AL Al yarmouk al IQ-P20575 IQ-P20147 Um Sitan IQ-P20068 ( collective - sector 4 ( Rahmaniya Erbil IKHA’A shamaly Tal Ab(u IQ-P20240 ( Imam Hamza IQ-P19732 Al salam Abbadan IQ-P20177 Syria ( IQ-P20082 IQ-P19744 Sanam Tal Ragrag ( ( IQ-P20093 Mabadi Iran ( IQ-P19742 Buwayr [2] IQ-P20684 ( ( Bulaij ( IQ-P20664 ( IQ-P20216 Tal Samir Zarqa Qubbat Abd ( (IQ-P2011(7 ( IQ-P20745 (Zakrak Arbid Baghdad ( ( ( ( ( IQ-P20590 ( Madhalla IQ-P20246 ( Al Saghir Huwaish IQ-P20250 IQ-P20174 IQ-P1R9a9m9a9di! ( Ali Hussin Sinjar District ( ( ( Tal Huser !\ Hay Al-Salam IQ-P20118 Tal Sirwal IQ-P20218( IQ-P20088 ( Amrini Jarn Upper ( IQ-P(20078 Village ( IQ-P20221 Um Shinin IQ-P20212 IQ-P19997 ( Al Khudrafiyah ( JordIQa-nP(20100 Najaf! Telafar District -

ISIS Assault on Civilization Targets Relics Once Saved from Looters

ISIS assault on civilization targets relics once saved from looters IRAQ ISIS assault on civilization targets relics once saved from looters Published March 11, 2015 · FoxNews.com 499 433 2364 When Jabbar Jaafar watched video of ISIS members with sledge-hammers smashing artifacts as old as antiquity, the Iraqi-born cultural activist was outraged over a loss he described as immeasurable. Jaafar's anger at the destruction of Iraqi artifacts, relics and statues by terrorists prompted him and his colleague, Iraqi archeologist Abdulamir Al Hamdani at Stonybrook University, to protest outside the White House Tuesday with 100 other cultural activists. Jaafar and Al Hamdani work with the group Saving Antiquities for Everyone, or SAFE, an organization founded in 2003 in response to the looting of the Iraq Museum during which thousands of objects were taken -- some 3,000 to 7,000 are still missing. "I couldn't sleep that night," Jaafar said, after watching the videotaped destruction by ISIS of artifacts in Mosul last month. "These objects are as old as civilization." "ISIS is destroying the heritage of mankind," said Jaafar, who came from Iraq to the U.S. in 2008 and worked for the Iraqi Cultural Center in northern Related Image Virginia. "These pieces -- more than 3,000 years old -- are gone forever. They can never be replaced." The latest target of the Islamic State is Hatra, a 2,000-year-old city and archaeological site in northern Iraq that had parts demolished by ISIS militants last week, according to Kurdish officials. The terrorists damaged and looted the city one day A protester is seen Tuesday outside the White House after bulldozing the historic city of to urge the administration to stop ISIS from destroying Nimrud. -

Icoa1808: the Syrian Heritage Archive Project in Berlin

ICOA1808: THE SYRIAN HERITAGE ARCHIVE PROJECT IN BERLIN Subtheme 03: Protecting and Interpreting Cultural Heritage in the Age of Digital Empowerment Session 2: Use of Digital Technology for Dissemination and Interpretation Location: Silver Oak 2, India Habitat Centre Time: December 13, 2017, 16:30 – 16:45 Author: Eva Nmeir Eva Nmeir is an art historian specialising in Islamic art, architecture and archaeology working with the Syrian Heritage Archive Project in Berlin and a freelance art educator with the Berlin State Museums Abstract: The Syrian Heritage Archive Project (SHAP) started in 2013 as a digitizing project of the collections of materials from renowned German scientific researchers. The project was located at both the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) and the Museum of Islamic Art (SMB) in Berlin, financed by the German Foreign Office, currently for the 5th project stage. The project group at the Museum of Islamic Art consists of a multidisciplinary team of different professionals of mostly Syrian and of German background. In addition to the basic database work, over the course of several years of dialogue and discussion within the core team, the emphasis has also been brought to other crucial focus points related to the material culture of Syria. In 2015, with a growing number of Syrians reaching Germany, the idea for the Multaka Project came up - an award-winning art education project enabling young Syrians guiding refugees through the collections of Berlin museums. In 2016, due to the worsening devastations caused by the ongoing Syrian war, an affiliated damage assessment project with regard to the historic monuments of Aleppo evolved, which, among others, develops a special app for professionals on spot. -

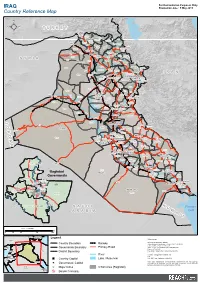

Country Reference Map

For Humanitarian Purposes Only IRAQ Production date : 5 May 2015 Country Reference Map T U R K E Y Ibrahim Al-Khalil (Habour) Zakho Zakho Amedi Dahuk Amedi Mergasur Dahuk Sumel Dahuk Rabia Mergasur Soran Sumel Shikhan Akre Haji Omaran Shikhan Akre Soran Telafar Choman Tilkaif Tilkaif Choman Shaqlawa Telafar Shaqlawa Sinjar Mosul Hamdaniya Rania Pshdar Sinjar Hamdaniya Erbil Ranya Qalat Erbil Dizah SYRIA Ba'aj Koisnjaq Mosul Erbil Ninewa Koisnjaq Dokan Baneh Dokan Makhmur Sharbazher Ba'aj Chwarta Penjwin Dabes Makhmur Penjwin Hatra Dabes Kirkuk Sulaymaniyah Chamchamal Shirqat Kirkuk IRAN Sulaymaniyah Hatra Shirqat Hawiga Daquq Sulaymaniyah Kirkuk Halabja Hawiga Chamchamal Darbandihkan Daquq Halabja Halabja Darbandikhan Baiji Tooz Khourmato Kalar Tikrit Baiji Tooz Ru'ua Kifri Kalar Tikrit Ru'ua Ka'im Salah Daur Kifri Ka'im Ana Haditha Munthiriya al-Din Daur Khanaqin Samarra Samarra Ka'im Haditha Khanaqin Balad Khalis Diyala Thethar Muqdadiya Balad Ana Al-Dujayl Khalis Muqdadiya Ba`aqubah Mandali Fares Heet Heet Ba'quba Baladrooz Ramadi Falluja Baghdad J Ramadi Rutba Baghdad Badra O Baramadad Falluja Badra Anbar Suwaira Azezia Turaybil Azezia R Musayab Suwaira Musayab D Ain Mahawil Al-Tamur Kerbala Mahawil Wassit Rutba Hindiya Na'miya Kut Ali Kerbala Kut Al-Gharbi A Ain BabylonHilla Al-Tamur Hindiya Ali Hashimiya Na'maniya Al-Gharbi Hashimiya N Kerbala Hilla Diwaniya Hai Hai Kufa Afaq Kufa Diwaniya Amara Najaf Shamiya Afaq Manathera Amara Manathera Qadissiya Hamza Rifa'i Missan Shamiya Rifa'i Maimouna Kahla Mejar Kahla Al-Kabi Qal'at Hamza -

Investment Map of Iraq 2016

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission Investment Map of Iraq 2016 Dear investor: Investment opportunities found in Iraq today vary in terms of type, size, scope, sector, and purpose. the door is wide open for all investors who wish to hold investment projects in Iraq,; projects that would meet the growing needs of the Iraqi population in different sectors. Iraq is a country that brims with potential, it is characterized by its strategic location, at the center of world trade routes giving it a significant feature along with being a rich country where I herby invite you to look at Iraq you can find great potentials and as one of the most important untapped natural resources which would places where untapped investment certainly contribute in creating the decent opportunities are available in living standards for people. Such features various fields and where each and characteristics creates favorable opportunities that will attract investors, sector has a crucial need for suppliers, transporters, developers, investment. Think about the great producers, manufactures, and financiers, potentials and the markets of the who will find a lot of means which are neighboring countries. Moreover, conducive to holding new projects, think about our real desire to developing markets and boosting receive and welcome you in Iraq , business relationships of mutual benefit. In this map, we provide a detailed we are more than ready to overview about Iraq, and an outline about cooperate with you In order to each governorate including certain overcome any obstacle we may information on each sector. In addition, face.