The Writings of Paul Gauguin by Linda Goddard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Gauguin 8 February to 28 June 2015

Media Release Paul Gauguin 8 February to 28 June 2015 With Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), the Fondation Beyeler presents one of the most important and fascinating artists in history. As one of the great European cultural highlights in the year 2015, the exhibition at the Fondation Beyeler brings together over fifty masterpieces by Gauguin from leading international museums and private collections. This is the most dazzling exhibition of masterpieces by this exceptional, groundbreaking French artist that has been held in Switzerland for sixty years; the last major retrospective in neighbouring countries dates back around ten years. Over six years in the making, the show is the most elaborate exhibition project in the Fondation Beyeler’s history. The museum is consequently expecting a record number of visitors. The exhibition features Gauguin’s multifaceted self-portraits as well as the visionary, spiritual paintings from his time in Brittany, but it mainly focuses on the world-famous paintings he created in Tahiti. In them, the artist celebrates his ideal of an unspoilt exotic world, harmoniously combining nature and culture, mysticism and eroticism, dream and reality. In addition to paintings, the exhibition includes a selection of Gauguin’s enigmatic sculptures that evoke the art of the South Seas that had by then already largely vanished. There is no art museum in the world exclusively devoted to Gauguin’s work, so the precious loans come from 13 countries: Switzerland, Germany, France, Spain, Belgium, Great Britain (England and Scotland), -

Irréalisme Et Art Moderne ,

Irréalisme et Art Moderne , . ....................- a ___•......________________I ! i t ... UNIVERSITE LIBRE DE BRUXELLES SIECLES 000584515 Mélanges Philippe Roberts-Jonés Irréalisme et Art Moderne Ê J ^ 'mmmt BBL Ouvrage publié avec le soutien de la Communauté française de Belgique et de la BBL. Section d’Histoire de l’Art et d’Archéologie de l’Université Libre de Bruxelles Irréalisme et Art Moderne LES VOIES DE L’IMAGINAIRE DANS L’ART DES XVIIIe, XIXe et XXe SIECLES Mélanges Philippe Roberts-Jones Edité par Michel Draguet Certains jours il ne faut pas craindre de nommer les choses impos sibles à décrire. Base et sommet, pour peu que les hommes remuent et divergent, rapidement s’effritent. Mais il y a la tension de la recherche, la répu gnance du sablier, l’itinéraire nonpareil, jusqu’à la folle faveur, une exigence de la conscience enfin à laquelle nous ne pouvons nous soustraire, avant de tomber au gouffre. René Char, Recherche de la base et du sommet, in: Œuvres complètes, introduction de Jean Roudaut, Paris, Gallimard (Bibliothèque de la Pléiade), 1983, p. 631. Aujourd’hui des racines ont poussé dans l’absence; le vent me prend aussi, j’aime, j’ai peur et quelquefois j’assume. Philippe Jones, Il y a vingt-cinq ans la mort, in: Graver au vif, repris in: Racine ouverte, Bruxelles, Le Cormier, 1976, p. 93. 5 P lanchel: G. Bertrand, Portrait de Philippe Roberts- Jones, 1974, huile sur toile, 81 x 65, collection privée. 6 A PROPOS DE PORTRAITS Rien n’est, ni ne doit être gratuit en art si ce n’est la joie ou la douleur de s’ac complir. -

PAUL GAUGUIN the PRINTS PAULGAUGUIN Tobia Bezzola Elizabeth Prelinger THEPRINTS

5243_Gauguin_001-160_ENGLISCH 26.09.12 11:10 Seite 2 PAUUL GAUGUIN THE PRINTS 5243_Gauguin_001-160_ENGLISCH 26.09.12 11:10 Seite 3 PAUL GAUGUIN THE PRINTS PAULGAUGUIN Tobia Bezzola Elizabeth Prelinger THEPRINTS PRESTEL Munich · London · New York 5243_Gauguin_001-160_ENGLISCH 26.09.12 11:10 Seite 4 5243_Gauguin_001-160_ENGLISCH 26.09.12 11:10 Seite 5 Foreword and Thanks 10 Christoph Becker Running Wild as Theme and Method 13 Tobia Bezzola CATALOGUE 18 Elizabeth Prelinger Savage Poetry – The Graphic Art of Paul Gauguin 20 The ‘Suite Volpini’ 29 The Portrait of Stéphane Mallarmé 51 The ‘Noa Noa Suite’ 59 ‘Manao Tupapau’ (She Thinks of the Spirit/The Spirit Thinks of Her) 87 ‘A Fisherman Drinking Beside His Canoe’ (Le Pêcheur buvant auprès de sa pirogue) 91 ‘Oviri’ (Savage) 95 The ‘Vollard Suite’ 103 ‘Le Sourire’ 131 APPENDIX 140 List of Works 143 Bibliography 153 Imprint 157 5243_Gauguin_001-160_ENGLISCH 26.09.12 11:10 Seite 6 5243_Gauguin_001-160_ENGLISCH 26.09.12 11:10 Seite 7 5243_Gauguin_001-160_ENGLISCH 26.09.12 11:10 Seite 8 5243_Gauguin_001-160_ENGLISCH 26.09.12 11:10 Seite 9 5243_Gauguin_001-160_ENGLISCH 26.09.12 11:10 Seite 10 10 Foreword and Thanks Christoph Becker The prints and drawings made by Paul Gauguin (b. June 7, 1848, in Paris; d. May 8, 1903, in Atuona on Hiva Oa, the Marquesas Islands) in the 1880s and 1890s were groundbreaking works of art. Gauguin is to be placed, as a painter, at modernism’s outset; and he became one of the most renowned artists of the era. His works on paper are a crucial element of his art and, more than this, it is impossible to fully understand Paul Gauguin the artist without paying due attention to them. -

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Exhibition Checklist Gauguin: Metamorphoses March 8-June 8, 2014

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Exhibition Checklist Gauguin: Metamorphoses March 8-June 8, 2014 Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 Vase Decorated with Breton Scenes, 1886–1887 Glazed stoneware (thrown by Ernest Chaplet) with gold highlights 11 5/16 x 4 3/4" (28.8 x 12 cm) Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 Cup Decorated with the Figure of a Bathing Girl, 1887–1888 Glazed stoneware 11 7/16 x 11 7/16" (29 x 29 cm) Dame Jillian Sackler Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 Vase with the Figure of a Girl Bathing Under the Trees, c. 1887–1888 Glazed stoneware with gold highlights 7 1/2 x 5" (19.1 x 12.7 cm) The Kelton Foundation, Los Angeles Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 Leda (Design for a China Plate). Cover illustration for the Volpini Suite, 1889 Zincograph with watercolor and gouache additions on yellow paper Composition: 8 1/16 x 8 1/16" (20.4 x 20.4 cm) Sheet: 11 15/16 x 10 1/4" (30.3 x 26 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund 03/11/2014 11:44 AM Gauguin: Metamorphoses Page 1 of 43 Gauguin: Metamorphoses Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 Bathers in Brittany from the Volpini Suite, 1889 Zincograph on yellow paper Composition: 9 11/16 x 7 7/8" (24.6 x 20 cm) Sheet: 18 7/8 x 13 3/8" (47.9 x 34 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund Paul Gauguin, French, 1848–1903 Edward Ancourt, Paris Breton Women Beside a Fence from the Volpini Suite, 1889 Zincograph on yellow paper Composition: 6 9/16 x 8 7/16" (16.7 x 21.4 cm) Sheet: 18 13/16 x 13 3/8" (47.8 x 34 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. -

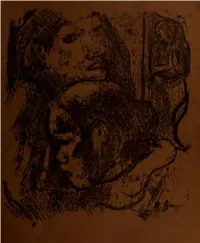

Paul Gauguin: Monotypes

Paul Gauguin: Monotypes Paul Gauguin: Monotypes BY RICHARD S. FIELD published on the occasion of the exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art March 23 to May 13, 1973 PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART Cover: Two Marquesans, c. 1902, traced monotype (no. 87) Philadelphia Museum of Art Purchased, Alice Newton Osborn Fund Frontispiece: Parau no Varna, 1894, watercolor monotype (no. 9) Collection Mr. Harold Diamond, New York Copyright 1973 by the Philadelphia Museum of Art Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-77306 Printed in the United States of America by Lebanon Valley Offset Company Designed by Joseph Bourke Del Valle Photographic Credits Roger Chuzeville, Paris, 85, 99, 104; Cliche des Musees Nationaux, Paris, 3, 20, 65-69, 81, 89, 95, 97, 100, 101, 105, 124-128; Druet, 132; Jean Dubout, 57-59; Joseph Klima, Jr., Detroit, 26; Courtesy M. Knoedler & Co., Inc., 18; Koch, Frankfurt-am-Main, 71, 96; Joseph Marchetti, North Hills, Pa., Plate 7; Sydney W. Newbery, London, 62; Routhier, Paris, 13; B. Saltel, Toulouse, 135; Charles Seely, Dedham, 16; Soichi Sunami, New York, 137; Ron Vickers Ltd., Toronto, 39; Courtesy Wildenstein & Co., Inc., 92; A. J. Wyatt, Staff Photographer, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Frontispiece, 9, 11, 60, 87, 106-123. Contents Lenders to the Exhibition 6 Preface 7 Acknowledgments 8 Chronology 10 Introduction 12 The Monotype 13 The Watercolor Transfer Monotypes of 1894 15 The Traced Monotypes of 1899-1903 19 DOCUMENTATION 19 TECHNIQUES 21 GROUPING THE TRACED MONOTYPES 22 A. "Documents Tahiti: 1891-1892-1893" and Other Small Monotypes 24 B. Caricatures 27 C. The Ten Major Monotypes Sent to Vollard 28 D. -

PALETTES Collection January 2013

PALETTES Collection January 2013 > 5 CLASSICAL ART > 6 PALETTES AUTHOR From the canvass itself to the type of brush used by the artist, Alain JAUBERT DIRECTOR from the historical, political or individual context of the painting to Alain JAUBERT the personality of the characters displayed in its features, Palette COPRODUCERS uncovers the endless secrets a work of art can hide. ARTE FRANCE, REUNION DES MUSEES NATIONAUX ET DU GRAND PALAIS DES Using the finest techniques (infrared, X rays, video animation...), Alain Jaubert dissects CHAMPS-ELYSEES, MUSEE DU LOUVRE the paintings to their most intimate levels, leading an investigation worthy of History's - SERVICE CULTUREL - PRODUCTIONS AUDIOVISUELLES, PALETTE PRODUCTION greatest detectives. DVD released by ARTE Video FORMAT AWARDS : 48 x 30 ', 2 x 60 ', 2003 Several awards among which "FIPA d'Argent" for Palettes Véronèse, 1989. AVAILABLE RIGHTS TV - DVD - Non-theatrical rights VERSIONS English - Spanish - German - French TERRITORY(IES) WORLDWIDE LIST OF EPISODES ANDY WARHOL [1928-1987] BACON [1909-1992] BONNARD [1867-1947] CEZANNE [1839-1906] CHARDIN [1699-1779] COURBET [1819-1877] DAME A LA LICORNE (LA) DAVID [1748-1825] DE LA TOUR [1593-1652] DELACROIX [1798-1863] DUCHAMP [1887-1968] EUPHRONIOS [~ 510 BEFORE CHRIST] FAYOUM [~ 117-138 BEFORE CHRIST] FRAGONARD [1732-1806] GAUGUIN [1848 - 1903] GERICAULT [1791-1824] GOYA [1746-1828] INGRES [1780-1867] GRUNEWALD [~ 1475-1528] HOKUSAI [1760-1849] KANDINSKY [1866-1944] KLEIN [1928-1962] LASCAUX LE CARAVAGE [1571-1610] LE LORRAIN [~ 1602-1682] -

The Ambassadors of Air Tahiti Nui Regarder Le Nombril», Explique- Jansé Wesson: Socially Aware T-Il

sommaire © MATAREVAPHOTO.COM Editorial Nos îles évoquent sans conteste le soleil, la joie de vivre et les paysages exceptionnels. Les charmes d’un paradis terrestre abondamment Tahiti & ses îles décrit par de nombreux navigateurs, écrivains, artistes. Ces charmes, nos visiteurs les retrouvent lors de leur séjour. Mais pour autant Tahiti 06 Carte de la Polynésie française n’est pas sans réserver des surprises. Nous en évoquons certaines dans ce nouveau numéro de RevaTahiti. 10 PORTFOLIO > Croisières reines Pour une découverte de manière originale de la Polynésie, nous vous 28 rendez-vous > Heiva I Tahiti invitons ainsi à embarquer pour des croisières de rêve, une autre 46 decouverte > Le vrai visage du capitaine Bligh façon d’aborder, au sens premier comme au sens figuré, nos îles. Toute leur beauté se dévoile lors de ces navigations. 54 rendez-vous Teahupo’o, histoire d’une légende > Surprise encore concernant les racines du Heiva I Tahiti, le plus 70 rendez-vous > Hokule’a en mission... important événement culturel de l’année et sans doute un des plus 78 rendez-vous > Baleines... ancien du monde car né à la fin du 19e siècle. Ces fêtes du Tiurai, 92 decouverte > Eo Himene, voix des Marquises devenus festivités du Heiva I Tahiti, sont, aujourd’hui, un temps fort de l’affirmation de l’identité polynésienne et, également, une grande 98 AGENDA célébration des traditions. 99 Les Bonnes ADRESSES Etonnement, sans doute, aussi à la vision des baleines qui sillonnent notre océan et nos côtes de juillet à septembre. En provenance des Monde mers glacées de l’Antarctique, leur milieu habituel, elles effectuent leur migration saisonnière en Polynésie. -

LES BONS VENTS VIENNENT DE L'étranger »: LA FABRICATION INTERNATIONALE DE LA GLOIRE DE GAUGUIN Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel

Les bons vents viennent de l’étranger Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel To cite this version: Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel. Les bons vents viennent de l’étranger : la fabrication internationale de la gloire de Gauguin. Revue d’Histoire Moderne et Contemporaine, Societe D’histoire Moderne et Con- temporaine, 2005, 2 (52-2), pp.113-147. 10.3917/rhmc.522.0113. hal-01479019 HAL Id: hal-01479019 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01479019 Submitted on 28 Feb 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. « LES BONS VENTS VIENNENT DE L'ÉTRANGER »: LA FABRICATION INTERNATIONALE DE LA GLOIRE DE GAUGUIN Béatrice Joyeux-prunel Belin | « Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine » 2005/2 no52-2 | pages 113 à 147 ISSN 0048-8003 ISBN 2701141680 Article disponible en ligne à l'adresse : -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- http://www.cairn.info/revue-d-histoire-moderne-et- contemporaine-2005-2-page-113.htm Document téléchargé depuis www.cairn.info - 134.158.231.197 03/03/2017 16h37. © Belin -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Pour citer cet article : -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Béatrice Joyeux-prunel, « « Les bons vents viennent de l'étranger »: la fabrication internationale de la gloire de Gauguin », Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine 2005/2 (no52-2), p. -

Gauguin, Gilgamesh, and the Modernist Aesthetic Allegory

© 2011 Jennifer Mary McBryan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED GAUGUIN, GILGAMESH, AND THE MODERNIST AESTHETIC ALLEGORY: THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF DESIRE IN NOA NOA by JENNIFER MARY McBRYAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School - New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Comparative Literature Written under the direction of Ben. Sifuentes-Jáuregui and approved by _________________________________ _________________________________ _________________________________ _________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey MAY, 2011 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Gauguin, Gilgamesh, and the Modernist Aesthetic Allegory: The Archaeology of Desire in Noa Noa By JENNIFER MARY McBRYAN Dissertation Director: Professor Ben. Sifuentes-Jáuregui This dissertation explores Paul Gauguin's Noa Noa (“fragrant” in Tahitian), a fictionalized “memoir” of his first journey to French Polynesia, which includes a transformative episode recounting a trip into the forest to collect wood for carving into sculptures. In Gauguin scholarship, this episode has provoked speculation because of the eroticized way in which the artist describes his relationship with his young Tahitian male guide on the expedition; several scholars have argued that this episode of Noa Noa is designed to trouble conventional bourgeois boundaries, while others have offered sharp postcolonial critiques. I offer a different reading of this episode, arguing that the forest journey in Noa Noa replays the journey to the cedar forest in the myth of Gilgamesh, and that the artist’s transplantation of this ancient Assyrian epic to a Polynesian setting adds a ii new layer to our understanding of the transnational and transhistorical nature of Gauguin's primitivism. -

Paul Gauguin 7

PAUL GAUGUIN 7. 6. 1848 – 8. 5. 1903 „Vše, čemu jsem se nau čil od jiných, mi jen stálo v cest ě. Mohu tak říci: nikdo m ě nic nenau čil. Na druhé stran ě je pravda, že toho znám tak málo. Ale dávám p řednost tomuto málu, které je mým vlastním výtvorem. A kdoví, zda se toto málo, až bude dáno k dispozici ostatním, nestane n ěč ím velkým?“ (Paul Gauguin) Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin se narodil 7. června 1848 v rue Notre-Dame de Lorette č. 52 (dnes č. 56) v Pa říži. Jeho matka, Aline Marie Chazalová, byla dcerou rytce André-Françoise Chazala (odsouzeného na dvacet let za pokus o vraždu své ženy) a Flory Tristanové, francouzské spisovatelky a bojovnice za práva d ělník ů a žen, jež byla nemanželskou dcerou špan ělského šlechtice. Gauguin ův otec Clovis p ůsobil jako redaktor republikánského deníku Le National. Po zvolení Ludvíka Napoleonského prezidentem se obával pronásledování kv ůli politickým názor ům, proto se v srpnu roku 1849 celá rodina vydala do Peru. B ěhem plavby Clovis Gauguin v dnešním Punta Arenas v Patagonii podlehl srde čnímu záchvatu, Aline Gauguinová s dětmi (Paulem a jeho o rok starší sestrou Fernande-Marcelline Marií) našla úto čišt ě u bratra svého d ěde čka v Lim ě. Rodina de Tristan y Moscoso byla nejen velmi bohatá, ale i politicky významná, ze ť d ěde čkova bratra dona Pia, don José Rufino Echenique, se roku 1851 stal prezidentem Peru. Malý Paul Gauguin v Lim ě vyr ůstal v přepychu, v exotickém sv ětě plném barev, na který nemohl po celý svůj život zapomenout. -

La Vie De Gauguin

I-'KMMK CARAÏBE AUX TOFRNKSO^ Collection Bakwin, New York ( 1889-1890). Cette peinture, que l'on appelle quelquefois La Nouvelle Ève, fut exécutée en Bretagne. Elle symbolise admirablement la puis- sante attraction qu'exercèrent sur Gauguin les pays exotiques, ces édens barbares. (Photo Galerie Charpentier.) PAPEETE (TAHITI). Ce paysage n'est pas sans mélancolie. Mais les îles du Plaisir ne sont-elles pas aussi les îles de la peur) .4 la nuit tombante, dans les cases des indigènes, s'allument les petites veilleuses destinées à écarter les mauvais esprits, les tupapaus. (Photo L. Gauthier.) LA VIE DE GAUOUF,N- AUTOPORTRAIT A L'AURKOLK. National Gallery of Art, Washington (1880). Dans ce portrait-charge, peint en Ihetagnc, Gauguin a accentué son profil d'Inca. Le peint) e croyait, fil effet, descendre les Incas. @ Librairie Hachette, 1961 Tous droits de traduction, de reproduction et d'adaptation réservés pour tous pays. IMAGES DE LA VIE DE GAUGUIN Au commencement était Flora Tristan, cette femme de feu, à qui Paul Gauguin, son petit-fils, ne fut pas sans ressembler. La vie de Flora fut extrêmement mouvementée. S'étant vouée à la cause des ouvriers, elle entreprit une tournée de propagande révolution- naire à travers la France. Elle ne put l'achever. Épuisée, elle mourut à Bordeaux (1844). Gauguin, au terme de sa vie, devait pareillement consacrer ses dernières forces à la défense des indigènes des Marquises. FLORA TKISTAX. B. N. Estampes. Collection Lamelle. (Photo Hachette.) PORTRAIT DE GAUGUIN ENFANT (1849), PAR JULES I,AURE. Peu après qu'ait été exécuté ce portrait, la famille Gauguin s'embarquait pour le Pérou. -

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2003

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2003 bron Van Gogh Museum Journal 2003. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam 2003 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_van012200301_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl / Rijksmuseum Vincent Van Gogh 7 Director's foreword The Van Gogh Museum mounts around six exhibitions every year, covering a wide range of subjects from the history of 19th and early 20th-century art. Many of these are international collaborations with partner museums, often involving loans from across the world. Yet, even for an institution accustomed to mounting large, temporary exhibitions, the show devoted to Van Gogh and Gauguin (The Art Institute of Chicago, 22 September 2001-13 January 2002, Van Gogh Museum, 9 February-2 June 2002) was of an order that fell far beyond the boundaries of our normal experience. In part this was because of the sheer scale of the enterprise and the various logistical challenges presented by this particular undertaking. It was also because the response from the public was almost overwhelming. Over a period of five months, some 739,000 visitors came to see Van Gogh and Gauguin in Amsterdam, making it the busiest art exhibition anywhere in the world in that year. But in the end it was the visual and emotional impact of this encounter between two great yet opposing talents that created an extraordinary show. From the beginnings of their first awareness of each other's art in the 1880s, through the brief but frenetic period when they were together in Arles in 1888, and then on to the end of their careers, the interaction between the two painters was revealed and analysed.