The Argumentative Litotes in the Analects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

University Interscholastic League Literary Criticism Contest • Invitational a • 2021

University Interscholastic League Literary Criticism Contest • Invitational A • 2021 Part 1: Knowledge of Literary Terms and of Literary History 30 items (1 point each) 1. A line of verse consisting of five feet that char- 6. The repetition of initial consonant sounds or any acterizes serious English language verse since vowel sounds in successive or closely associated Chaucer's time is known as syllables is recognized as A) hexameter. A) alliteration. B) pentameter. B) assonance. C) pentastich. C) consonance. D) tetralogy. D) resonance. E) tetrameter. E) sigmatism. 2. The trope, one of Kenneth Burke's four master 7. In Greek mythology, not among the nine daugh- tropes, in which a part signifies the whole or the ters of Mnemosyne and Zeus, known collectively whole signifies the part is called as the Muses, is A) chiasmus. A) Calliope. B) hyperbole. B) Erato. C) litotes. C) Polyhymnia. D) synecdoche. D) Urania. E) zeugma. E) Zoe. 3. Considered by some to be the most important Irish 8. A chronicle, usually autobiographical, presenting poet since William Butler Yeats, the poet and cele- the life story of a rascal of low degree engaged brated translator of the Old English folk epic Beo- in menial tasks and making his living more wulf who was awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize for through his wit than his industry, and tending to Literature is be episodic and structureless, is known as a (n) A) Samuel Beckett. A) epistolary novel. B) Seamus Heaney. B) novel of character. C) C. S. Lewis. C) novel of manners. D) Spike Milligan. D) novel of the soil. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

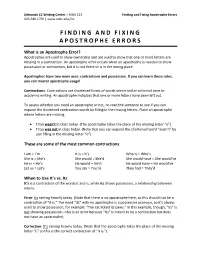

Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 |

Edmonds CC Writing Center | MUK 113 Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 | www.edcc.edu/lsc FINDING AND FIXING APOSTROPHE ERRORS What is an Apostrophe Error? Apostrophes are used to show ownership and are used to show that one or more letters are missing in a contraction. An apostrophe error occurs when an apostrophe is needed to show possession or contraction, but it is not there or is in the wrong place. Apostrophes have two main uses: contractions and possession. If you can learn these rules, you can master apostrophe usage! Contractions: Contractions are shortened forms of words which add an informal tone to academic writing. An apostrophe indicates that one or more letters have been left out. To assess whether you need an apostrophe or not, re-read the sentence to see if you can expand the shortened contraction words by filling in the missing letters. Place an apostrophe where letters are missing. Thao wasn’t in class today. (The apostrophe takes the place of the missing letter “o”). Thao was not in class today. (Note that you can expand the shortened word “wasn’t” by just filling in the missing letter “o”). These are some of the most common contractions: I am = I’m It is = It’s Who is = Who’s She is = She’s She would = She’d She would have = She would’ve He is = He’s He would = He’d He would have = He would’ve Let us = Let’s You are = You’re They had = They’d When to Use It’s vs. -

Chapter 1 Negation in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective

Chapter 1 Negation in a cross-linguistic perspective 0. Chapter summary This chapter introduces the empirical scope of our study on the expression and interpretation of negation in natural language. We start with some background notions on negation in logic and language, and continue with a discussion of more linguistic issues concerning negation at the syntax-semantics interface. We zoom in on cross- linguistic variation, both in a synchronic perspective (typology) and in a diachronic perspective (language change). Besides expressions of propositional negation, this book analyzes the form and interpretation of indefinites in the scope of negation. This raises the issue of negative polarity and its relation to negative concord. We present the main facts, criteria, and proposals developed in the literature on this topic. The chapter closes with an overview of the book. We use Optimality Theory to account for the syntax and semantics of negation in a cross-linguistic perspective. This theoretical framework is introduced in Chapter 2. 1 Negation in logic and language The main aim of this book is to provide an account of the patterns of negation we find in natural language. The expression and interpretation of negation in natural language has long fascinated philosophers, logicians, and linguists. Horn’s (1989) Natural history of negation opens with the following statement: “All human systems of communication contain a representation of negation. No animal communication system includes negative utterances, and consequently, none possesses a means for assigning truth value, for lying, for irony, or for coping with false or contradictory statements.” A bit further on the first page, Horn states: “Despite the simplicity of the one-place connective of propositional logic ( ¬p is true if and only if p is not true) and of the laws of inference in which it participate (e.g. -

An Investigation of Possession in Moroccan Arabic

Family Agreement: An Investigation of Possession in Moroccan Arabic Aidan Kaplan Advisor: Jim Wood Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2017 Abstract This essay takes up the phenomenon of apparently redundant possession in Moroccan Arabic.In particular, kinship terms are often marked with possessive pronominal suffixes in constructions which would not require this in other languages, including Modern Standard Arabic. In the following example ‘sister’ is marked with the possessive suffix hā ‘her,’ even though the person in question has no sister. ﻣﺎ ﻋﻨﺪﻫﺎش ُﺧﺘﻬﺎ (1) mā ʿend-hā-sh khut-hā not at-her-neg sister-her ‘She doesn’t have a sister’ This phenomenon shows both intra- and inter-speaker variation. For some speakers, thepos- sessive suffix is obligatory in clausal possession expressing kinship relations, while forother speakers it is optional. Accounting for the presence of the ‘extra’ pronoun in (1) will lead to an account of possessive suffixes as the spell-out of agreement between aPoss◦ head and a higher element that contains phi features, using Reverse Agree (Wurmbrand, 2014, 2017). In regular pronominal possessive constructions, Poss◦ agrees with a silent possessor pro, while in sentences like (1), Poss◦ agrees with the PP at the beginning of the sentence that expresses clausal posses- sion. The obligatoriness of the possessive suffix for some speakers and its optionality forothers is explained by positing that the selectional properties of the D◦ head differ between speakers. In building up an analysis, this essay draws on the proposal for the construct state in Fassi Fehri (1993), the proposal that clitics are really agreement markers in Shlonsky (1997), and the account of clausal possession in Boneh & Sichel (2010). -

Determining Gender Markedness in Wari' Joshua Birchall University Of

Determining Gender Markedness in Wari’ Joshua Birchall University of Montana 1. Introduction Grammatical gender is rare across Amazonian languages. The language families that possess grammatical gender properties are Arawak, Chapakuran and Arawá. Wari’, a Chapakuran (Txapakura) language of Brazil, is unusual among these languages in that it possesses three gender categories: what we can refer to as masculine, feminine and neuter. While efforts have been made to posit the functionally unmarked gender in Arawak and Arawá languages, no such analysis has been given for any Chapakuran language. In this paper I propose that neuter is the functionally unmarked grammatical gender of Wari’. Aikhenvald (1999:84) states that masculine is the functionally unmarked gender for non-Caribbean Arawak languages, while Dixon (1999:298) claims that feminine is the unmarked gender in Arawá languages. Functionally unmarked gender refers to the gender that is obligatorily assigned when its designation is otherwise opaque. With attempts, as in Greenberg (1987), to claim a genetic relationship between Chapakuran languages and the Arawak and Arawá families, the presence of gender is a major grammatical similarity and possible motivating factor for such a hypothesis and thus should be examined. In order to investigate this claim, I first present an outline of the Wari’ gender distinctions and then proceed to describe how gender is manifested within the clause. A case is then presented for neuter as the functionally unmarked gender. This claim is further examined for its historical implications, especially regarding genetic affiliation. All of the data1 used in this paper come from Everett and Kern (1997). 2. Gender Distinctions The three gender distinctions we find in Wari’ are largely determined by the semantic domain of the noun. -

Dear AP Literature Students

Dear AP Literature Students: Welcome! I’m excited to meet you in the fall and to revel in the amazing reading! Before you return to school in August, please complete the following work to get our conversation started: 1. Carefully read and annotate All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy and Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro. When you read McCarthy, I would recommend bookmarking this page as it provides translations of the Spanish: http://cormacmccarthy.cookingwithmarty.com/wp- content/uploads/ATPHTrans.pdf. 2. Next, watch the animated film Persepolis (based on the graphic novel by Marjane Satrapi) and think about how it connects to our summer reading and why. You can rent it on Netflix or Amazon or possibly check it out at your local library. Yes, it is in French with subtitles J 3. Lastly, actively study the vocabulary lists "Literary Allusions" and "Literary Terms" (both in this packet). I would recommend not passively memorizing flashcards or a Quizlet, but instead using the words in your everyday conversations and in your writing to secure them in your memory and into your own personal lexicon! On the first day of AP week, you will be tested on the summer work. The test on the works of fiction will be primarily objective rather than interpretive, and it will include quotation identification, plot and setting points, and character descriptions. The test on the vocabulary will be matching. The point of the test is to ensure that you have read actively and studied the vocabulary so that you can use the works and words immediately. -

Adnominal Possession: Combining Typological and Second Language Perspectives

Adnominal possession: combining typological and second language perspectives Björn Hammarberg and Maria Koptjevskaja-Tamm 1. Introduction The notion of possession and its linguistic manifestations have been a popular topic in linguistic literature for a long time. What we will attempt here is to explore the domain of adnominal possession - pos- sessive relations and their manifestations within the noun phrase - in one particular language from two combined points of view: the ty- pological characteristics of the system, and the picture that emerges from second language learners' attempts to handle adnominal pos- session in production. We are focusing on Swedish, a language with a distinctive and rather elaborate system of adnominal possession. Our aim is twofold: to present an overview of how the Swedish sys- tem of adnominal possessive constructions works, and to show how acquisitional aspects connect with typological aspects in this domain. The English phrases Peter's hat, my son and a boy's leg all exem- plify prototypical cases of adnominal possession whereby one entity, the possessee, referred to by the head of the possessive noun phrase, is represented as possessed in one way or another by another entity, the possessor, referred to by the attribute. It has become a common- place in linguistics that possession is a difficult, if not impossible, notion to grasp (for a survey of adnominal possession in a cross- linguistic perspective cf. Koptjevskaja-Tamm 2001). However, even though it seems impossible to give a reasonable general definition for all the meanings covered by possessive constructions across lan- guages and even in one language, we can still provide criteria for identifying a possessive construction, or possessive constructions in a language. -

Serial Verb Constructions: Argument Structural Uniformity and Event Structural Diversity

SERIAL VERB CONSTRUCTIONS: ARGUMENT STRUCTURAL UNIFORMITY AND EVENT STRUCTURAL DIVERSITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Melanie Owens November 2011 © 2011 by Melanie Rachel Owens. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/db406jt2949 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Beth Levin, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Joan Bresnan I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Vera Gribanov Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Abstract Serial Verb Constructions (SVCs) are constructions which contain two or more verbs yet behave in every grammatical respect as if they contain only one. -

A Pragmatic Study of Litotes in Trump's Political Speeches

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 11, Issue 3, 2020 A Pragmatic Study of Litotes in Trump's Political Speeches Wafaa Mokhlosa, Ali Abdulkareem Mukheefb*, a,bUniversity of Babylon, Iraq, Email: b*[email protected] Litotes is defined as a figure of speech by which the affirmative is expressed by denying its contrary. The current study is concerned with identifying and analysing litotes in Donald Trump's political speeches on pragmatic level. The study aims at identifying the illocutionary force of litotes, the functions of litotes, which maxim of Grice is mainly breached in the production of litotes to produce implicature, and which type of litotes is heavily used by Trump. The analysis is curried out on data consists of four texts from Trump's speeches during being president from 2016 to 2019. The study concludes that the illocutionary force of litotes in most of the times is asserting. Litotes is used mainly to fulfil the function of emphasis, but it can be used to perform the functions of encouraging and inciting. Trump uses contrary litotes in most of his speeches. Key words: Pragmatics, Litotes, Illocutionary force, Implicature, Functions. Introduction Politicians use different strategies and devices to convince their audience or gain their support. Figurative language is one of these strategies that are mainly based on the use of certain figures of speech such as irony, euphemism, metaphor, litotes etc. according to Griffiths (2006:81). Understanding figurative language requires a great interaction between semantics and pragmatics. Therefore, to understand the meaning of certain figure of speech a total knowledge of the context is required.