Research on the Management System of Imperial Kiln of Ancient China Under Tang Ying

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

Ming China As a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Winter 12-15-2018 Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Duan, Weicong, "Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620" (2018). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1719. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1719 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Dissertation Examination Committee: Steven B. Miles, Chair Christine Johnson Peter Kastor Zhao Ma Hayrettin Yücesoy Ming China as a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 by Weicong Duan A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 St. Louis, Missouri © 2018, -

Issue 13 Final Version

RHETORICAL SPACE Culture of Curiosity in Yangcai under Emperor Qianlong’s Reign Chih-En Chen Department of the History of Art and Archaeology PhD Candidate ABSTRACT This research is arranged into three sections in order to elaborate on the hybrid innovation in yangcai. Firstly, the usage of pictorial techniques on porcelain will be discussed, followed by the argument that the modelling technique in the Qianlong period could be the revival of Buddhist tradition combined with European pictoriality. The second section continues the discussion of non-traditional attributes in terms of the ontology of porcelain patterns. Although it has been widely accepted that Western-style decorations were applied to the production of the Qing porcelain, the other possibility will be purported here by stating that the decorative pattern is a Chinese version of the multicultural product. The last section explores style and identity. By reviewing the history of Chinese painting technique, art historians can realise the difference between knowing and performing. Artworks produced in the Emperor Qianlong’s reign were more about Emperor Qianlong’s preference than the capability of the artists. This political reason differentiated the theory and practice in Chinese history of art. This essay argues that the design of yangcai is substantially part of the Emperor Qianlong’s portrait, which represents his multicultural background, authority over various civilisations, and transcendental identity as an emperor bridging the East and the West. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Chih-En Chen is a PhD Candidate at the Department of the History of Art and Archaeology at SOAS, University of London. Before he arrived his current position, he worked for Christie’s Toronto Office (2013-2014) and Waddington’s Auctioneers in Canada (2014-2018). -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

The Interaction Between Ethnic Relations and State Power: a Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Georgia State University Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Dissertations Department of Sociology 5-27-2008 The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911 Wei Li Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Li, Wei, "The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss/33 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INTERACTION BETWEEN ETHNIC RELATIONS AND STATE POWER: A STRUCTURAL IMPEDIMENT TO THE INDUSTRIALIZATION OF CHINA, 1850-1911 by WEI LI Under the Direction of Toshi Kii ABSTRACT The case of late Qing China is of great importance to theories of economic development. This study examines the question of why China’s industrialization was slow between 1865 and 1895 as compared to contemporary Japan’s. Industrialization is measured on four dimensions: sea transport, railway, communications, and the cotton textile industry. I trace the difference between China’s and Japan’s industrialization to government leadership, which includes three aspects: direct governmental investment, government policies at the macro-level, and specific measures and actions to assist selected companies and industries. -

The Layout of Power and Space in Jingdezhen Imperial

HE LAYOUT OF POWER AND SPACE IN JINGDEZHEN TIMPERIAL FACTORY Jia Zhan Jingdezhen Ceramic Institute Jiangxi, China Keywords: Jingdezhen Imperial Factory, regulation of government building, techno- logical system, power-space 1. Introduction Space has social attribute, and the study of space in human geography gradually pro- ceeds from the exterior to the interior and eventually into the complicated structure of the society. The study of culture in geography no longer treats culture as the object of spatial be- havior, instead, it focuses on culture itself, exploring the function of space in constructing and shaping culture [1].The concentrated and introverted space of imperial power is typical of this function. In the centralized system of absolute monarchy, the emperor with arbitrary authority, controlled and supervised the whole nation and wield his unchecked power at will. The idea of spatial practice and representations of space proposed by Henri Lefebvre provides a good reference for the study of the above-mentioned issues, such as the material environment, allocation, organization and ways of representation of production [2].To study the production path and control mode of the landscape from the perspective of power, we can see that cul- ture is not only represented through landscape, but also shapes the landscape, they interact- ing with each other in a feedback loop [3].We can also understand the relationship between social environment and space of imperial power which starts from the emperor, moves down to the imperial court and then to the provinces. This method of social government is also reflected in the Imperial Factory, the center of imperial power in ceramics. -

Learning to Read in Late Imperial China

This watermark does not appear in the registered version - http://www.clicktoconvert.com Studies on Asia, series II, vol. 1, num. 1 LEARNING TO READ IN LATE IMPERIAL CHINA Li Yu, Emory University Introduction1 On the morning of the tenth day of the third lunar month in the year 1766, dozens of delegates on a Korean solstitial embassy entered a Temple of Chaste Woman located in a village within Yongping Prefecture in Northern China (in today’s Hebei Province). They found a school next to the inner gate of the temple and half a dozen children sitting there studying. What amazed all of them was that, in spite of the noise the delegation had made, these children were not in the least distracted and concentrated on their studies as if nothing had happened. A few moments later when Hong Taeyong (1731-1783), the nephew of the secretary of the embassy, arrived at the gate, an interpreter excitedly reported this marvelous scene to him. Suspicious of the veracity of the story, Hong went inside to investigate. What he discovered and later recorded in his memoir turns out to be a rare piece of evidence showing us a scene of children learning to read in early modern China. Despite the fact that reading was greatly emphasized by educators and policy-makers in early modern China, very little was written on how children were actually taught to read. Previous studies on Chinese elementary education mainly focus on the issue of literacy, the content of education, educational institutions, and educators' theories on teaching.2 Although primers and 1 The article has benefited from comments by Galal Walker, Mark Bender, Cynthia Brokaw, Patricia Sieber, Victor Mair, J. -

Studies in Late Qing Dynasty Battle Paintings*

HONGXING ZHANG STUDIES IN LATE QING DYNASTY BATTLE PAINTINGS* PART ONE DOCUMENTS FOR FOUR CHINESE BATTLE PAINTINGS IN WESTERN COLLECTIONS n his seminal work on European culture in the late medieval period, Johan Huizinga (1872-1945) I observed that history has always been more possessed by the problem of origins and development than by those of decline and fall. He writes: "When studying any period, we are always looking for the promise of what the next is to bring."' This observation still holds true if applied to the study of nineteen-century Chinese art, a burgeoning field in recent years. Thus, in art historical discourse on this period, much attention has been given to the search for the origins of modern Chinese culture. Many works have focused on the artistic productions shaped by new cultural forces, such as Sino-west- ern pictures, popular prints, early photography, and above all paintings of the Shanghai School. The nineteenth century has been treated as if it had been no more than the infancy of modern China. Con- sequently, the contemporary court cultural production has been largely neglected. Since the art at the late Qing court has been so poorly studied that reliable dates and attributions have not been established for even the most important artworks commissioned by the Manchu court, I want to postpone the reappraisal of the nature of the Chinese art during the nineteenth century. The present study considers dating and attribution problems of four large battle paintings in Western col- lections - one painting in the Mrs. Cecile McTaggart Collection, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada (fig. -

Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Genre and Empire: Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies Yuanfei Wang University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Wang, Yuanfei, "Genre and Empire: Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 938. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/938 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/938 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Genre and Empire: Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies Abstract Chinese historical romance blossomed and matured in the sixteenth century when the Ming empire was increasingly vulnerable at its borders and its people increasingly curious about exotic cultures. The project analyzes three types of historical romances, i.e., military romances Romance of Northern Song and Romance of the Yang Family Generals on northern Song's campaigns with the Khitans, magic-travel romance Journey to the West about Tang monk Xuanzang's pilgrimage to India, and a hybrid romance Eunuch Sanbao's Voyages on the Indian Ocean relating to Zheng He's maritime journeys and Japanese piracy. The project focuses on the trope of exogamous desire of foreign princesses and undomestic women to marry Chinese and social elite men, and the trope of cannibalism to discuss how the expansionist and fluid imagined community created by the fiction shared between the narrator and the reader convey sentiments of proto-nationalism, imperialism, and pleasure. -

Download Article

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 94 4th International Conference on Economy, Judicature, Administration and Humanitarian Projects (JAHP 2019) Historical Evolution and Development: Formation of Multi-ethnic Complementary Patterns in Yunnan Tibetan Area Xuekun Li Yuqin Zhang* College of Economics and Management College of Economics and Management Yunnan Agricultural University Yunnan Agricultural University Kunming, China 650201 Kunming, China 650201 *Corresponding Author Abstract—The Yunnan Tibetan Area refers to the Diqing performed "integration, confrontation and integration" with Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Yunnan Province. It is the local aboriginal ancestors, which is a historical scroll of the Yunnan Tibetan Area in "Tibet and the Tibetan Areas of the evolution of long-term ethnic relations. The historical pattern Four Provinces (Qinghai, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Gansu)" of multi-ethnic embedded distribution in Tibetan areas of mentioned in the Sixth Tibet Work Symposium. During the Yunnan gradually formed. long-term history of evolution, dated from the earliest multi- ethnic activities, the history of Yunnan Tibetan Area can be The Yunnan Tibetan area is geographically far from the mainly divided into following four stages: the conflict between Tibetan cultural center and away from the Han cultural Tang, Tubo and Nanzhao; Chieftain Mu's rule; the great center, making it culturally retain the characteristics of unification period of the Yuan Dynasty; and Gushi Khan of the Tibetan areas on the Tibet Plateau on the one hand. On the Heshuote tribe of Mongolia defeated Chieftain Mu. Against the other hand, it has long been an important "national corridor" background of conflict and collision, the multi-ethnic for movement and migration of Qiang, Di, Rong and other complementary advancement and the construction of the ethnic groups in the history, and the meeting point of the identification of the same region have gradually taken shape. -

Liquidity, Technicity, and the Predictive Turn in Chinese Ceramics

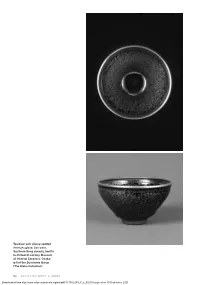

Tea bowl with silvery-spotted tenmoku glaze, Jian ware, Southern Song dynasty, twelfth to thirteenth century. Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka; gift of the Sumitomo Group (The Ataka Collection). 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00230 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00230 by guest on 30 September 2021 Liquidity, Technicity, and the Predictive Turn in Chinese Ceramics JEFFREY MOSER Jeff Wall’s notion of liquid intelligence turns on the dialectic of modernity. On one side of the divide are the dry mechanisms of the camera, which metaphorically and literally express the industrial processes that brought them into being. On the other side is water, which “symbolically represents an archaism in photography, one that is admitted in the process, but also excluded, contained or channelled by its hydraulics.” 1 Wall’s attraction to liquidity is unreservedly nostalgic—it harkens back to archaic processes and what he understands as the ever more remote possibility of fortuity in art-making—and it seeks to find, in the developing fluid of the photograph, a bridge back to the “sense of immersion in the incalculable” that modernity has alienated. 2 For him, liquidity and chance are not simply of the past, they have been made past by the totality of a “modern vision” that inex - orably subjugates them through industry and design. 3 Wall’s formulation implicitly probes the semantic contradiction that imbues Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’s famous passage with such force: Where, he inquires, is the liquid elided when “all that is solid melts into air?” 4 The juxtaposition of Wall’s essay “Photography and Liquid Intelligence” with his Milk (1984) raises the tension simmering in Wall’s formula. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise).