Artistic Exchange Under Different Royal Patrons in 18Th-Century China and Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Japanese Palace in Dresden: a Highlight of European 18Th-Century

都市と伝統的文化 The ‘Japanese Palace’ in Dresden: A Highlight of European 18th-century Craze for East-Asia. Cordula BISCHOFF Dresden, seat of government and capital of present-day federal state Saxony, now benefits more than any other German city from its past as a royal residence. Despite war-related destructions is the cityscape today shaped by art and architecture with a history of 500 years. There is possibly no other place in Germany where to find so many exceptional artworks concentrated in such a small area. This accumulation is a result of the continuosly increasing significance of the Dresden court and a gain in power of the Saxon Wettin dynasty. The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation was a conglomeration of more than 350 large and tiny territories. The 50 to 100 leading imperial princes struggled in a constant competition to maintain their positions. 1) In 1547 the Saxon Duke Moritz(1521-1553)was declared elector. Thus Saxony gained enormous political significance, as the seven, in 18th century nine electors, were the highest-ranking princes. They elected the Roman-German emperor and served as his innermost councils. The electors of Saxony and of the Palatinate were authorised to represent the emperor in times of vacancy. At the same time in 16th century Saxony rose due to its silver mining industry to one of the richest German territorial states. 2) In the second half of the 17th century the Saxon court even counted among the most important European courts. A peak of political power was reached under Frederick August(us)I. -

Index Volume 46

THE NEWSLETTER FOR COLLECTORS, DEALERS AND INVESTORS September 2019 – August 2020 Volume 46 A Adams, 83, 117, 130 Index Volume 46 Advertising, 4-5, 11, 14, 20-21, 23, 35, 37, 40, 42, 47, 49, Numbers 1 - 12 53, 58-59, 71, 73, 78-79, 82-83, 95, 98-99, 107, 115, 119, 121, September 2019 - August 2020 124, 129-131, 133, 138-139, 143 Pages 1 - 144 Alabaster, 83, 118 Aluminum, 2, 5, 11, 14, 43, 47, 50-51, 63, 143 Amberina, 97, 100 PAGES ISSUES DATE Amphora, 1, 4, 74 1-12 No. 1 September 2019 Anna Pottery, 127 13-24 No. 2 October 2019 Architectural, 7, 32, 91 25-36 No. 3 November 2019 Argenta, 23, 25, 28 37-48 No. 4 December 2019 Argy-Rousseau, 131 49-60 No. 5 January 2020 Art Deco, 23, 28, 34-35, 59, 71, 78-79, 95, 119, 136 61-72 No. 6 February 2020 Art Glass, 10, 23, 97, 100 73-84 No. 7 March 2020 Art Nouveau, 4, 75, 101, 105, 131, 143 85-96 No. 8 April 2020 Art Pottery, 4, 85 97-108 No. 9 Arts & Crafts, 6-7, 59, 131, 143 May 2020 Austria, 4 109-120 No. 10 June 2020 Auto, 59 121-132 No. 11 July 2020 Avon, 95 133-144 No. 12 August 2020 B Blanket Chest, 47, 85, 92 Baccarat, 11, 41 Blown Glass, 12, 107 Badge, 96 Blue Glass, 83, 107 Bank, 17, 57, 70, 110, 143 Blue Onion, 35 Barber, 95, 138 Boehm, 107 Barometer, 131 Bookends, 23, 83, 85, 89, 107-108 Baseball, 14, 79, 94, 106, 141 Bossons, 59 Basket, 18, 71, 93, 95, 99, 107, 109, 113, 125 Bottle, 9, 11, 14, 21, 23, 35, 38, 40, 46-47, 59, 64, 88, 93-95, 97, 104- Bavaria, 46, 58, 96, 120 105, 107, 122, 126, 130-131, 143 Beatles, 3, 38, 47, 127, 129, 143 Bottle Cap, 131 Beehive, 47 Box, 2, 6-7, 11-12, -

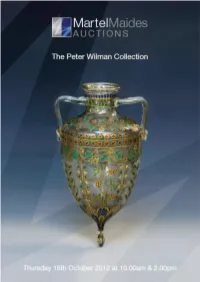

The Wilman Collection

The Wilman Collection Martel Maides Auctions The Wilman Collection Martel Maides Auctions The Wilman Collection Martel Maides Auctions The Wilman Collection Lot 1 Lot 4 1. A Meissen Ornithological part dessert service 4. A Derby botanical plate late 19th / early 20th century, comprising twenty plates c.1790, painted with a central flower specimen within with slightly lobed, ozier moulded rims and three a shaped border and a gilt line rim, painted blue marks square shallow serving dishes with serpentine rims and and inscribed Large Flowerd St. John's Wort, Derby rounded incuse corners, each decorated with a garden mark 141, 8½in. (22cm.) diameter. or exotic bird on a branch, the rims within.ects gilt £150-180 edges, together with a pair of large square bowls, the interiors decorated within.ects and the four sides with 5. Two late 18th century English tea bowls a study of a bird, with underglaze blue crossed swords probably Caughley, c.1780, together with a matching and Pressnumern, the plates 8¼in. (21cm.) diameter, slop bowl, with floral and foliate decoration in the dishes 6½in. (16.5cm.) square and the bowls 10in. underglaze blue, overglaze iron red and gilt, the rims (25cm.) square. (25) with lobed blue rings, gilt lines and iron red pendant £1,000-1,500 arrow decoration, the tea bowls 33/8in. diameter, the slop bowl 2¼in. high. (3) £30-40 Lot 2 2. A set of four English cabinet plates late 19th century, painted centrally with exotic birds in Lot 6 landscapes, within a richly gilded foliate border 6. -

Meissen Porcelain: Precision, Presentation, and Preservation

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 Meissen Porcelain: Precision, Presentation, and Preservation. How Artistic and Technological Significance Influence Conservation Protocol Nicole Peters West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Peters, Nicole, "Meissen Porcelain: Precision, Presentation, and Preservation. How Artistic and Technological Significance Influence Conservation Protocol" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 756. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/756 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Meissen Porcelain: Precision, Presentation, and Preservation. How Artistic and Technological Significance Influence Conservation Protocol. Nicole Peters Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Approved by Janet Snyder, Ph.D., Committee Chair Rhonda Reymond, Ph.D. Jeff Greenham, M.F.A. Michael Belman, M.S. Division of Art and Design Morgantown, West Virginia 2011 Keywords: Meissen porcelain, conservation, Fürstenzug Mural, ceramic riveting, material substitution, object replacement Copyright 2011 Nicole L. -

Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century

Global Positioning: Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wong, John. 2012. Global Positioning: Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9282867 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 – John D. Wong All rights reserved. Professor Michael Szonyi John D. Wong Global Positioning: Houqua and his China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century Abstract This study unearths the lost world of early-nineteenth-century Canton. Known today as Guangzhou, this Chinese city witnessed the economic dynamism of global commerce until the demise of the Canton System in 1842. Records of its commercial vitality and global interactions faded only because we have allowed our image of old Canton to be clouded by China’s weakness beginning in the mid-1800s. By reviving this story of economic vibrancy, I restore the historical contingency at the juncture at which global commercial equilibrium unraveled with the collapse of the Canton system, and reshape our understanding of China’s subsequent economic experience. I explore this story of the China trade that helped shape the modern world through the lens of a single prominent merchant house and its leading figure, Wu Bingjian, known to the West by his trading name of Houqua. -

1 Der Goldene Reiter - Ein Wahrzeichen Dresdens

Originalveröffentlichung in: Die Restaurierung des Goldenen Reiters 2001 - 2003 : Dokumentation [Hrsg.: Landeshauptstadt Dresden, Liegenschaftsamt], Dresden 2004, S. 4-13 1 Der Goldene Reiter - Ein Wahrzeichen Dresdens Dr. Barbara Bechter „Des Höchstseel. Königs Augusti II. Statua" steht in platzbeherr • 1.1 Die Modelle zum Reiterdenkmal2 schender Lage auf dem Neustädter Markt in Dresden. Das in Überlebensgröße ausgeführte Reiterdenkmal zeigt den sächsi In den Akten wird das Denkmal erstmals 1704 genannt. Am schen Kurfürsten Friedrich August I. (16701733), genannt Au 27. Januar 1704 bestätigte der Hofbildhauer Balthasar Permoser gust der Starke, seit 1697 als August II. König von Polen. Er ist in dem König „nochmahls", dass er den Auftrag für ein solches der Art römischer Imperatoren gekleidet und sitzt auf einem sich Denkmal annehme: „Allerdurchlauchtigster Großmächtigster aufbäumenden Pferd. König und ChurFürst, Allergnädigster Herr! Nachdehm Eu. Königl. Wohl schon sehr bald nach seiner Krönung wünschte der junge Majst. Nochmahls allergnädigst resolviret seyn, das Pferd mit der Herrscher eine seiner Person und Position angemessene reprä darauff sizenden Persohn, so Eu:Maj: praesentiren soll, von mir sentative Darstellung in Form eines Reiterstandbildes. Obwohl von verferttigen zu lassen..." verschiedenen Bildhauern am sächsischen Hof immer wieder Mo Gleichzeitig bat er um Zahlung seines ausstehenden Gehal delle hierzu angefertigt wurden, zog sich die tatsächliche Ausfüh tes, um sich eine neue Werkstatt in Altendresden bauen zu -

Oval Salts - Quicktopic Free Message Board Hosting Page 1 of 104

Oval Salts - QuickTopic free message board hosting Page 1 of 104 Oval Salts February 2016 OpenSalts.US Last Month Pattern Glass Past Topics Oval Salts Links Oval shaped salts of any material. Back to Message Board TOPIC: Oval Salts V All messages 1-532 of 532 1 Gift QT Pro Debi Raitz I guess I'll leave it up to you if you want to include pedestals instead of Upload 02-01-2016 sticking to flat oval shapes. pictures, 01:25 AM customize ET (US) the look, 2 and more. mary Can our ovals have pointy ends?? Like are what "they" call boat shaped 02-01-2016 09:32 AM considered to be oval?? Just early morning wondering ---- ET (US) 3 mary 02-01-2016 09:41 AM ET (US) Oval Salts - QuickTopic free mess... 8/26/2016 Oval Salts - QuickTopic free message board hosting Page 2 of 104 Okay I start this time - Silver with cobalt - Have not had a chance to look for the maker yet 4 mary 02-01-2016 09:42 AM ET (US) German silver with birds 5 mary 02-01-2016 09:43 AM ET (US) London sterling date mark 1781 6 mary 02-01-2016 09:46 AM ET (US) Unmarked and unknown metal composition - but I love it --- 7 Gosh Mary, you are still awake? Poor baby. Good and plenty comes in Lynda pink and white? Did not know that. I am not liking black licorice, so never LaLonde noticed pink good and plenty. 02-01-2016 Hope we can do ovals with points. -

Issue 13 Final Version

RHETORICAL SPACE Culture of Curiosity in Yangcai under Emperor Qianlong’s Reign Chih-En Chen Department of the History of Art and Archaeology PhD Candidate ABSTRACT This research is arranged into three sections in order to elaborate on the hybrid innovation in yangcai. Firstly, the usage of pictorial techniques on porcelain will be discussed, followed by the argument that the modelling technique in the Qianlong period could be the revival of Buddhist tradition combined with European pictoriality. The second section continues the discussion of non-traditional attributes in terms of the ontology of porcelain patterns. Although it has been widely accepted that Western-style decorations were applied to the production of the Qing porcelain, the other possibility will be purported here by stating that the decorative pattern is a Chinese version of the multicultural product. The last section explores style and identity. By reviewing the history of Chinese painting technique, art historians can realise the difference between knowing and performing. Artworks produced in the Emperor Qianlong’s reign were more about Emperor Qianlong’s preference than the capability of the artists. This political reason differentiated the theory and practice in Chinese history of art. This essay argues that the design of yangcai is substantially part of the Emperor Qianlong’s portrait, which represents his multicultural background, authority over various civilisations, and transcendental identity as an emperor bridging the East and the West. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Chih-En Chen is a PhD Candidate at the Department of the History of Art and Archaeology at SOAS, University of London. Before he arrived his current position, he worked for Christie’s Toronto Office (2013-2014) and Waddington’s Auctioneers in Canada (2014-2018). -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Aodayixike Qingzhensi Baisha, 683–684 Abacus Museum (Linhai), (Ordaisnki Mosque; Baishui Tai (White Water 507 Kashgar), 334 Terraces), 692–693 Abakh Hoja Mosque (Xiang- Aolinpike Gongyuan (Olym- Baita (Chowan), 775 fei Mu; Kashgar), 333 pic Park; Beijing), 133–134 Bai Ta (White Dagoba) Abercrombie & Kent, 70 Apricot Altar (Xing Tan; Beijing, 134 Academic Travel Abroad, 67 Qufu), 380 Yangzhou, 414 Access America, 51 Aqua Spirit (Hong Kong), 601 Baiyang Gou (White Poplar Accommodations, 75–77 Arch Angel Antiques (Hong Gully), 325 best, 10–11 Kong), 596 Baiyun Guan (White Cloud Acrobatics Architecture, 27–29 Temple; Beijing), 132 Beijing, 144–145 Area and country codes, 806 Bama, 10, 632–638 Guilin, 622 The arts, 25–27 Bama Chang Shou Bo Wu Shanghai, 478 ATMs (automated teller Guan (Longevity Museum), Adventure and Wellness machines), 60, 74 634 Trips, 68 Bamboo Museum and Adventure Center, 70 Gardens (Anji), 491 AIDS, 63 ack Lakes, The (Shicha Hai; Bamboo Temple (Qiongzhu Air pollution, 31 B Beijing), 91 Si; Kunming), 658 Air travel, 51–54 accommodations, 106–108 Bangchui Dao (Dalian), 190 Aitiga’er Qingzhen Si (Idkah bars, 147 Banpo Bowuguan (Banpo Mosque; Kashgar), 333 restaurants, 117–120 Neolithic Village; Xi’an), Ali (Shiquan He), 331 walking tour, 137–140 279 Alien Travel Permit (ATP), 780 Ba Da Guan (Eight Passes; Baoding Shan (Dazu), 727, Altitude sickness, 63, 761 Qingdao), 389 728 Amchog (A’muquhu), 297 Bagua Ting (Pavilion of the Baofeng Hu (Baofeng Lake), American Express, emergency Eight Trigrams; Chengdu), 754 check -

Imperial China and the Silk Roads: Travels, Flows, and Trade

Anno 2 | Numero 2 (marzo 2019) www.viaggiatorijournal.com Viaggiatori. Circolazioni scambi ed esilio 4 Imperial China and the Silk Roads: travels, flows, and trade a cura di Filippo Costantini www.viaggiatorijournal.com Direttore scientifico Fabio D’Angelo - [email protected] ISSN 2532-7623 (online) – ISSN 2532-7364 (stampa) VIAGGIATORI. CIRCOLAZIONI SCAMBI ED ESILIO www.viaggiatorijournal.com Direttore della rivista: Fabio D’Angelo [email protected] Vicedirettore: Pierre-Marie Delpu [email protected] Segreteria di redazione: Luisa Auzino [email protected] Luogo di pubblicazione: Napoli, Via Nazionale 33, 80143 Periodicità: semestrale (settembre/marzo) ___________________________ Direttore della pubblicazione/Editore: Fabio D’Angelo ISSN 2532-7623 (online) ISSN 2532-7364 (stampa) Pubblicazione: Anno 2, Numero 2, 27 marzo 2019 Deposito legale:____________________________ Comitato scientifico: Mateos Abdon, Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary, Sarah Badcock, Geneviève Bührer-Thierry, Pierre-Yves Beaurepaire Gilles Bertrand, Agostino Bistarelli, Hélène Blais, Alfredo Buccaro, Catherine Brice, François Brizay, Albrecht Burkardt, Giulia Delogu, Santi Fedele, Rivka Feldhay, Marco Fincardi, Jorge Flores, Myriam Houssay-Holzschuch, Mario Infelise, Maurizio Isabella, Rita Mazzei, Rolando Minuti, Sarga Moussa, Dhruv Raina, Sandra Rebok, Fiammetta Sabba, Isabelle Sacareau, Lorenzo Scillitani, Mikhail Talalay, Anna Tylusińska- Kowalska, Ezio Vaccari, Sylvain Venayre, Éric Vial. Comitato di lettura: Irini -

SCHLOESSERLAND SACHSEN. Fireplace Restaurant with Gourmet Kitchen 01326 Dresden OLD SPLENDOR in NEW GLORY

Savor with all your senses Our family-led four star hotel offers culinary richness and attractive arrangements for your discovery tour along Sa- xony’s Wine Route. Only a few minutes walking distance away from the hotel you can find the vineyard of Saxon master vintner Klaus Zimmerling – his expertise and our GLORY. NEW IN SPLENDOR OLD SACHSEN. SCHLOESSERLAND cuisine merge in one of Saxony’s most beautiful castle Dresden-Pillnitz Castle Hotel complexes into a unique experience. Schloss Hotel Dresden-Pillnitz August-Böckstiegel-Straße 10 SCHLOESSERLAND SACHSEN. Fireplace restaurant with gourmet kitchen 01326 Dresden OLD SPLENDOR IN NEW GLORY. Bistro with regional specialties Phone +49(0)351 2614-0 Hotel-owned confectioner’s shop [email protected] Bus service – Elbe River Steamboat jetty www.schlosshotel-pillnitz.de Old Splendor in New Glory. Herzberg Żary Saxony-Anhalt Finsterwalde Hartenfels Castle Spremberg Fascination Semperoper Delitzsch Torgau Brandenburg Senftenberg Baroque Castle Delitzsch 87 2 Halle 184 Elsterwerda A 9 115 CHRISTIAN THIELEMANN (Saale) 182 156 96 Poland 6 PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR OF STAATSKAPELLE DRESDEN 107 Saxony 97 101 A13 6 Riesa 87 Leipzig 2 A38 A14 Moritzburg Castle, Moritzburg Little Buch A 4 Pheasant Castle Rammenau Görlitz A72 Monastery Meissen Baroque Castle Bautzen Ortenburg Colditz Albrechtsburg Castle Castle Castle Mildenstein Radebeul 6 6 Castle Meissen Radeberg 98 Naumburg 101 175 Döbeln Wackerbarth Dresden Castle (Saale) 95 178 Altzella Monastery Park A 4 Stolpen Gnandstein Nossen Castle -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise).