Issue 13 Final Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: the Great Qing and the Maritime World

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: The Great Qing and the Maritime World in the Long Eighteenth Century Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultüt der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Chung-yam PO Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Harald Fuess Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Joachim Kurtz Datum: 28 June 2013 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Acknowledgments 3 Emperors of the Qing Dynasty 5 Map of China Coast 6 Introduction 7 Chapter 1 Setting the Scene 43 Chapter 2 Modeling the Sea Space 62 Chapter 3 The Dragon Navy 109 Chapter 4 Maritime Customs Office 160 Chapter 5 Writing the Waves 210 Conclusion 247 Glossary 255 Bibliography 257 1 Abstract Most previous scholarship has asserted that the Qing Empire neglected the sea and underestimated the worldwide rise of Western powers in the long eighteenth century. By the time the British crushed the Chinese navy in the so-called Opium Wars, the country and its government were in a state of shock and incapable of quickly catching-up with Western Europe. In contrast with such a narrative, this dissertation shows that the Great Qing was in fact far more aware of global trends than has been commonly assumed. Against the backdrop of the long eighteenth century, the author explores the fundamental historical notions of the Chinese maritime world as a conceptual divide between an inner and an outer sea, whereby administrators, merchants, and intellectuals paid close and intense attention to coastal seawaters. Drawing on archival sources from China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and the West, the author argues that the connection between the Great Qing and the maritime world was complex and sophisticated. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

The Life and Scholarship of the Eighteenth- Century Amdo Scholar Sum Pa Mkhan Po Ye Shes Dpal ’Byor (1704-1788)

Renaissance Man From Amdo: the Life and Scholarship of the Eighteenth- Century Amdo Scholar Sum Pa Mkhan Po Ye Shes Dpal ’Byor (1704-1788) The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40050150 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Renaissance Man From Amdo: The Life and Scholarship of the Eighteenth-Century Amdo Scholar Sum pa Mkhan po Ye shes dpal ’byor (1704-1788) ! A dissertation presented by Hanung Kim to The Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History and East Asian Languages Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April, 2018 © 2018 – Hanung Kim All rights reserved. ! Leonard W. J. van der Kuijp Hanung Kim Renaissance Man From Amdo: The Life and Scholarship of the Eighteenth- Century Amdo Scholar Sum pa Mkhan po Ye shes dpal ’byor (1704-1788) Abstract! This dissertation examines the new cultural developments in eighteenth-century northeastern Tibet, also known as Amdo, by looking into the life story of a preeminent monk- scholar, Sum pa Mkhan po Ye shes dpal ’byor (1708-1788). In the first part, this study corroborates what has only been sensed by previous scholarship, that is, the rising importance of Amdo in Tibetan cultural history. -

The Layout of Power and Space in Jingdezhen Imperial

HE LAYOUT OF POWER AND SPACE IN JINGDEZHEN TIMPERIAL FACTORY Jia Zhan Jingdezhen Ceramic Institute Jiangxi, China Keywords: Jingdezhen Imperial Factory, regulation of government building, techno- logical system, power-space 1. Introduction Space has social attribute, and the study of space in human geography gradually pro- ceeds from the exterior to the interior and eventually into the complicated structure of the society. The study of culture in geography no longer treats culture as the object of spatial be- havior, instead, it focuses on culture itself, exploring the function of space in constructing and shaping culture [1].The concentrated and introverted space of imperial power is typical of this function. In the centralized system of absolute monarchy, the emperor with arbitrary authority, controlled and supervised the whole nation and wield his unchecked power at will. The idea of spatial practice and representations of space proposed by Henri Lefebvre provides a good reference for the study of the above-mentioned issues, such as the material environment, allocation, organization and ways of representation of production [2].To study the production path and control mode of the landscape from the perspective of power, we can see that cul- ture is not only represented through landscape, but also shapes the landscape, they interact- ing with each other in a feedback loop [3].We can also understand the relationship between social environment and space of imperial power which starts from the emperor, moves down to the imperial court and then to the provinces. This method of social government is also reflected in the Imperial Factory, the center of imperial power in ceramics. -

The Rise of Steppe Agriculture

The Rise of Steppe Agriculture The Social and Natural Environment Changes in Hetao (1840s-1940s) Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg i. Br. vorgelegt von Yifu Wang aus Taiyuan, V. R. China WS 2017/18 Erstgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Sabine Dabringhaus Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Dr. Franz-Josef Brüggemeier Vorsitzender des Promotionsausschusses der Gemeinsamen Kommission der Philologischen und der Philosophischen Fakultät: Prof. Dr. Joachim Grage Datum der Disputation: 01. 08. 2018 Table of Contents List of Figures 5 Acknowledgments 1 1. Prologue 3 1.1 Hetao and its modern environmental crisis 3 1.1.1 Geographical and historical context 4 1.1.2 Natural characteristics 6 1.1.3 Beacons of nature: Recent natural disasters in Hetao 11 1.2 Aims and current state of research 18 1.3 Sources and secondary materials 27 2. From Mongol to Manchu: the initial development of steppe agriculture (1300s-1700s) 32 2.1 The Mongolian steppe during the post-Mongol empire era (1300s-1500s) 33 2.1.1 Tuntian and steppe cities in the fourteenth century 33 2.1.2 The political impact on the steppe environment during the North-South confrontation 41 2.2 Manchu-Mongolia relations in the early seventeenth century 48 2.2.1 From a military alliance to an unequal relationship 48 2.2.2 A new management system for Mongolia 51 2.2.3 Divide in order to rule: religion and the Mongolian Policy 59 2.3 The natural environmental impact of the Qing Dynasty's Mongolian policy 65 2.3.1 Agricultural production 67 2.3.2 Wild animals 68 2.3.3 Wild plants of economic value 70 1 2.3.4 Mining 72 2.4 Summary 74 3. -

A New Vision of Painting

INTRODUCTION A New Vision of Painting Inside the Forbidden City one day, late in his reign, the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736–95) might have left his office and throne room at the east end of the Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxindian) and walked west down its main corridor toward the Three Rarities Studio (Sanxitang).1 Under Qianlong’s patronage, the arts flourished at the Chinese imperial court: the Three Rarities Studio, merely a tiny room at the westernmost end of the hall, was reserved for his enjoyment and connoisseurship of the vast imperial painting and calligraphy collection. Before stepping over the raised threshold into the antechamber preceding the studio, he likely paused at the sight before him. Perfectly framed by the doorway was a room with a distinctive floor of blue-and- white porcelain tiles and decoratively latticed windows that receded to a moon gate, which opened onto a secluded private garden occupied by two men (figure I.1). The older man was present- ing a branch of blossoming plum to the younger man, and both were casually dressed in scholars’ robes rather than court costume. The scene was one of tranquility, leisure, and personal connection, a sharp contrast to the formality and the political responsibility of the east end of the hall. Although initially this view appeared real, once the emperor stepped through the doorway its true nature would have been revealed as a special type of eighteenth- century court painting (figure I.2). Scenic illusion paintings tongjinghua( ) are massive wall- and ceiling- mounted paintings in full color on silk, produced collaboratively by the best 3 00i-380_Kleutghen_4p.indb 3 7/17/14 5:25 PM I.2 Anonymous (attributed to Giuseppe Castiglione and Jin Tingbiao), Spring’s Peaceful Message, mid- eighteenth century. -

Section 3 – Constitutionalism and the Wars with China and Russia

Section 3 – Constitutionalism and the wars with China and Russia Topic 58 – The struggle to revise the unequal treaties What strategies did Japan employ in order to renegotiate the unequal treaties signed with | 226 the Western powers during the final years of the shogunate? The problem of the unequal treaties The treaties that the shogunate signed with the Western powers in its final years were humiliating to the Japanese people due to the unequal terms they forced upon Japan. Firstly, any foreign national who committed a crime against a Japanese person was tried, not in a Japanese court, but in a consular court set up by the nation of the accused criminal.1 Secondly, Japan lost the right, just as many other Asian countries had, to set its own import tariffs. The Japanese people of the Meiji period yearned to end this legal discrimination imposed by the Western powers, and revision of the unequal treaties became Japan's foremost diplomatic priority. *1=The exclusive right held by foreign countries to try their own citizens in consular courts for crimes committed against Japanese people was referred to as the right of consular jurisdiction, which was a form of extraterritoriality. In 1872 (Meiji 5), the Iwakura Mission attempted to discuss the revision of the unequal treaties with the United States, but was rebuffed on the grounds that Japan had not reformed its legal system, particularly its criminal law. For this reason, Japan set aside the issue of consular jurisdiction and made recovery of its tariff autonomy the focal point of its bid to revise the unequal treaties. -

Curriculum Vitae

EUGENIO MENEGON History Department Boston University 226 Bay State Road Boston, Massachusetts 02215 USA Telephone: 617-353-8308 Fax: 617-353-2556 Email: [email protected] Webpages: http://blogs.bu.edu/emenegon/ http://www.bu.edu/history/people/faculty/eugenio-menegon/ http://www.bu.edu/asian/center-for-the-study-of-asia/welcome/ [Updated February 2014] EDUCATION Ph.D. University of California at Berkeley, Department of History, May 2002. M.A. University of California at Berkeley, Group in Asian Studies, May 1994. B.A. University of Venice “Ca’ Foscari,” Italy, summa cum laude, Oriental Languages and Literatures (Chinese), May 1991. Specialization Certificate People’s University of China (中國人民大學) and Institute of Qing History (清史研究所), Beijing, P.R. China, Ming-Qing History and Chinese Language, 1989-90. Certificate Beijing Language Institute (北京語言學院), Beijing, P.R. China, Chinese Language, Fall 1988. PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS Director, Boston University Center for the Study of Asia (BUCSA), July 2012-present Associate Professor, Boston University, Department of History, 2010-present. Assistant Professor, Boston University, Department of History; 2004-2010. Researcher, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (Belgium), Department of Oriental and Slavonic Studies – Sinology; October 2002-August 2004. Research Fellow, University of San Francisco, EDS-Stewart Chair in Chinese-Western Cultural History, The Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western Cultural History, Center for the Pacific Rim, May- August 2002. 2E. Menegon – Curriculum – 2 PUBLICATIONS BOOKS Ancestors, Virgins, and Friars: Christianity as a Local Religion in Late Imperial China. Harvard- Yenching Institute Monograph Series, no. 69. Harvard University Asia Center and Harvard University Press, 2009. Recipient of the 2011 Joseph Levenson Book Prize for best scholarly work on pre-1900 China, awarded by the China and Inner Asia Council of the Association for Asian Studies. -

Liquidity, Technicity, and the Predictive Turn in Chinese Ceramics

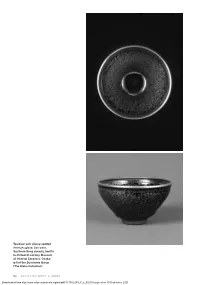

Tea bowl with silvery-spotted tenmoku glaze, Jian ware, Southern Song dynasty, twelfth to thirteenth century. Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka; gift of the Sumitomo Group (The Ataka Collection). 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00230 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00230 by guest on 30 September 2021 Liquidity, Technicity, and the Predictive Turn in Chinese Ceramics JEFFREY MOSER Jeff Wall’s notion of liquid intelligence turns on the dialectic of modernity. On one side of the divide are the dry mechanisms of the camera, which metaphorically and literally express the industrial processes that brought them into being. On the other side is water, which “symbolically represents an archaism in photography, one that is admitted in the process, but also excluded, contained or channelled by its hydraulics.” 1 Wall’s attraction to liquidity is unreservedly nostalgic—it harkens back to archaic processes and what he understands as the ever more remote possibility of fortuity in art-making—and it seeks to find, in the developing fluid of the photograph, a bridge back to the “sense of immersion in the incalculable” that modernity has alienated. 2 For him, liquidity and chance are not simply of the past, they have been made past by the totality of a “modern vision” that inex - orably subjugates them through industry and design. 3 Wall’s formulation implicitly probes the semantic contradiction that imbues Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’s famous passage with such force: Where, he inquires, is the liquid elided when “all that is solid melts into air?” 4 The juxtaposition of Wall’s essay “Photography and Liquid Intelligence” with his Milk (1984) raises the tension simmering in Wall’s formula. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Visit to the Palace Museum, Beijing, April 2014, a Handling Session in the Study Room

1. Visit to the Palace Museum, Beijing, April 2014, a Handling Session in the Study Room In April 2014 I visited the Palace Museum in Beijing with a group of colleagues after the spring series of auctions in Hong Kong. April is a good month to visit Beijing, as the weather is mild and if one is fortunate, the magnolia trees and peonies are just starting to flower. On this occasion, we were fortunate to be with some of our colleagues from Hong Kong, one of which had very good contacts with the curatorial staff at the Museum. This allowed us access to parts of the Palace that the general public are not able to visit, such as the Lodge of Fresh Fragrance, where the emperor Qianlong would hold imperial family banquets and on New Year’s Day would accept congratulations from officials and would invite them to watch operas. (Fig 2. and 3.). It is now used as VIP reception rooms for the Museum. However, the real highlight of the visit was the handling session that we were invited to attend in the study room. All the pieces that we handled were generally of the finest quality, but had sustained some damage, which made their Fig 1. Side Entrance to the Palace Museum. handling less of a worrying exercise. This week’s article is a little unusual in that it is a written record of this handling session. By its very nature, handling pieces is a very visual and tactile experience and can be difficult to convey in words, but I will endeavour to give a sense of this and provide comparisons where applicable. -

Production and Consumption of Chinese Enamelled Porcelain, C.1728-C.1780

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/91791 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications ‘The colours of each piece’: production and consumption of Chinese enamelled porcelain, c.1728-c.1780 Tang Hui A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick, Department of History March 2017 Declaration I, Tang Hui, confirm that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted for a degree at another university. Cover Illustrations: Upper: Decorating porcelain in enamel colours, Album leaf, Watercolours, c.1750s. Hong Kong Maritime Museum, HKMM2012.0101.0021(detail). Lower: A Canton porcelain shop waiting for foreign customers. Album leaf, Watercolours, c.1750s, Hong Kong Maritime Museum, HKMM2012.0101.0033(detail). Table of Contents Declaration .............................................................................................................................. 2 Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................... i List of Illustrations