A Review of S. W. Bushell's Research on Chinese Ceramic Art in Late

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 13 Final Version

RHETORICAL SPACE Culture of Curiosity in Yangcai under Emperor Qianlong’s Reign Chih-En Chen Department of the History of Art and Archaeology PhD Candidate ABSTRACT This research is arranged into three sections in order to elaborate on the hybrid innovation in yangcai. Firstly, the usage of pictorial techniques on porcelain will be discussed, followed by the argument that the modelling technique in the Qianlong period could be the revival of Buddhist tradition combined with European pictoriality. The second section continues the discussion of non-traditional attributes in terms of the ontology of porcelain patterns. Although it has been widely accepted that Western-style decorations were applied to the production of the Qing porcelain, the other possibility will be purported here by stating that the decorative pattern is a Chinese version of the multicultural product. The last section explores style and identity. By reviewing the history of Chinese painting technique, art historians can realise the difference between knowing and performing. Artworks produced in the Emperor Qianlong’s reign were more about Emperor Qianlong’s preference than the capability of the artists. This political reason differentiated the theory and practice in Chinese history of art. This essay argues that the design of yangcai is substantially part of the Emperor Qianlong’s portrait, which represents his multicultural background, authority over various civilisations, and transcendental identity as an emperor bridging the East and the West. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Chih-En Chen is a PhD Candidate at the Department of the History of Art and Archaeology at SOAS, University of London. Before he arrived his current position, he worked for Christie’s Toronto Office (2013-2014) and Waddington’s Auctioneers in Canada (2014-2018). -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

The Layout of Power and Space in Jingdezhen Imperial

HE LAYOUT OF POWER AND SPACE IN JINGDEZHEN TIMPERIAL FACTORY Jia Zhan Jingdezhen Ceramic Institute Jiangxi, China Keywords: Jingdezhen Imperial Factory, regulation of government building, techno- logical system, power-space 1. Introduction Space has social attribute, and the study of space in human geography gradually pro- ceeds from the exterior to the interior and eventually into the complicated structure of the society. The study of culture in geography no longer treats culture as the object of spatial be- havior, instead, it focuses on culture itself, exploring the function of space in constructing and shaping culture [1].The concentrated and introverted space of imperial power is typical of this function. In the centralized system of absolute monarchy, the emperor with arbitrary authority, controlled and supervised the whole nation and wield his unchecked power at will. The idea of spatial practice and representations of space proposed by Henri Lefebvre provides a good reference for the study of the above-mentioned issues, such as the material environment, allocation, organization and ways of representation of production [2].To study the production path and control mode of the landscape from the perspective of power, we can see that cul- ture is not only represented through landscape, but also shapes the landscape, they interact- ing with each other in a feedback loop [3].We can also understand the relationship between social environment and space of imperial power which starts from the emperor, moves down to the imperial court and then to the provinces. This method of social government is also reflected in the Imperial Factory, the center of imperial power in ceramics. -

Liquidity, Technicity, and the Predictive Turn in Chinese Ceramics

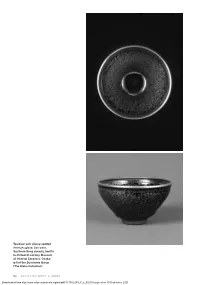

Tea bowl with silvery-spotted tenmoku glaze, Jian ware, Southern Song dynasty, twelfth to thirteenth century. Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka; gift of the Sumitomo Group (The Ataka Collection). 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00230 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00230 by guest on 30 September 2021 Liquidity, Technicity, and the Predictive Turn in Chinese Ceramics JEFFREY MOSER Jeff Wall’s notion of liquid intelligence turns on the dialectic of modernity. On one side of the divide are the dry mechanisms of the camera, which metaphorically and literally express the industrial processes that brought them into being. On the other side is water, which “symbolically represents an archaism in photography, one that is admitted in the process, but also excluded, contained or channelled by its hydraulics.” 1 Wall’s attraction to liquidity is unreservedly nostalgic—it harkens back to archaic processes and what he understands as the ever more remote possibility of fortuity in art-making—and it seeks to find, in the developing fluid of the photograph, a bridge back to the “sense of immersion in the incalculable” that modernity has alienated. 2 For him, liquidity and chance are not simply of the past, they have been made past by the totality of a “modern vision” that inex - orably subjugates them through industry and design. 3 Wall’s formulation implicitly probes the semantic contradiction that imbues Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’s famous passage with such force: Where, he inquires, is the liquid elided when “all that is solid melts into air?” 4 The juxtaposition of Wall’s essay “Photography and Liquid Intelligence” with his Milk (1984) raises the tension simmering in Wall’s formula. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Visit to the Palace Museum, Beijing, April 2014, a Handling Session in the Study Room

1. Visit to the Palace Museum, Beijing, April 2014, a Handling Session in the Study Room In April 2014 I visited the Palace Museum in Beijing with a group of colleagues after the spring series of auctions in Hong Kong. April is a good month to visit Beijing, as the weather is mild and if one is fortunate, the magnolia trees and peonies are just starting to flower. On this occasion, we were fortunate to be with some of our colleagues from Hong Kong, one of which had very good contacts with the curatorial staff at the Museum. This allowed us access to parts of the Palace that the general public are not able to visit, such as the Lodge of Fresh Fragrance, where the emperor Qianlong would hold imperial family banquets and on New Year’s Day would accept congratulations from officials and would invite them to watch operas. (Fig 2. and 3.). It is now used as VIP reception rooms for the Museum. However, the real highlight of the visit was the handling session that we were invited to attend in the study room. All the pieces that we handled were generally of the finest quality, but had sustained some damage, which made their Fig 1. Side Entrance to the Palace Museum. handling less of a worrying exercise. This week’s article is a little unusual in that it is a written record of this handling session. By its very nature, handling pieces is a very visual and tactile experience and can be difficult to convey in words, but I will endeavour to give a sense of this and provide comparisons where applicable. -

Production and Consumption of Chinese Enamelled Porcelain, C.1728-C.1780

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/91791 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications ‘The colours of each piece’: production and consumption of Chinese enamelled porcelain, c.1728-c.1780 Tang Hui A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick, Department of History March 2017 Declaration I, Tang Hui, confirm that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted for a degree at another university. Cover Illustrations: Upper: Decorating porcelain in enamel colours, Album leaf, Watercolours, c.1750s. Hong Kong Maritime Museum, HKMM2012.0101.0021(detail). Lower: A Canton porcelain shop waiting for foreign customers. Album leaf, Watercolours, c.1750s, Hong Kong Maritime Museum, HKMM2012.0101.0033(detail). Table of Contents Declaration .............................................................................................................................. 2 Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................... i List of Illustrations -

The Porcelain City Jingdezhen in the Eighteenth Century

1a.Finlay, Pilgrim Art 8/7/09 3:30 PM Page 17 The Pilgrim Art by Robert Finlay 1 The Porcelain City Jingdezhen in the Eighteenth Century in the opening years of the eighteenth century, François-xavier dentrecolles es- tablished a church in Jingdezhen, the great porcelain center on the Chang river in the province of Jiangxi, southeastern China. A recruit for the French mission of the Jesuits, he was thirty-five years old when he arrived in Canton in 1698 on board the Amphitrite, a ship purchased by the Compagnie des indes orientales (French East india Company), a state-sponsored syndicate, from louis xiv (r. 1643–1715).1 dentrecolles was not the most eminent or controversial of the approximately fifty Jesuits who served with him over the next four decades, but he had a passion for the curious and unusual, along with a gift for sifting and marshaling information. After working in Jingdezhen for more than two decades, he presided over the French missionary residence in beijing until 1732, during which he translated and com- mented on Chinese accounts of medicine, currency, and government administra- tion. He also sent reports home on the raising of silkworms, the crafting of artifi- cial flowers in silk and paper, the manufacture of synthetic pearls, methods of smallpox inoculation, and the cultivation of tea, ginseng, and bamboo. This repre- sented the sort of engagement with indigenous culture that the Society of Jesus ex- pected of its learned priests. A fellow Jesuit declared in a funeral eulogy for dentre- colles in beijing in 1741 that everyone had “a high opinion of his wisdom.” His assignment to Jingdezhen suggests that dentrecolles’s superiors recognized his tal- ent for inquiry and analysis from the start. -

Artistic Exchange Under Different Royal Patrons in 18Th-Century China and Europe

Artistic exchange under different royal patrons in 18th-century China and Europe: A comparison between Augustus II’s Meissen porcelain manufactory and Qianlong’s Imperial Household Department clock workshop. Master Thesis Name:Tianyi Huang Student Number: s2077078 Email: [email protected] First reader: Prof. dr. A.T. Gerritsen Second reader: Prof. dr. R.J. Baarsen Educational program and Specialization: MA Arts and Culture, Museums and Collections Academic Year: 2018-2019 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Significance of the research 3 1.3 Literature review 4 1.4 Research questions 9 1.5 Methodology 9 Chapter 2 Encounter 12 2.1 Augustus the Strong encountering porcelain 12 2.2 Qianlong Emperor encountering clocks 15 2.3 Comparisons and contrasts in encounters 19 Chapter 3 Acquisition 22 3.1 The acquisition of porcelain 22 3.2 The acquisition of clocks 23 3.3 Discussion 27 Chapter 4 Transformation 29 4.1. Meissen manufactory 29 4.1.1 Motivation 29 4.1.2 Organization and procedures 30 4.2 Imperial clock workshop 32 4.2.1. Motivation 32 4.2.2. Organization and procedures 34 4.3 Discussion 35 Chapter 5 Hybridization and localization 37 5.1 Localization: Meissen porcelain and the public display of ambition 37 5.1.1 From Chinoiserie to Baroque: red dragon tableware and blue onion 1 pattern 37 5.1.2 Displaying ambition in public space 40 5.2 Hybridization: Qianlong Imperial clocks, Ceremonial Paraphernalia and the Miniature Empire 44 5.2.1 Qianlong imperial style: visual hybrid of multi-ethnic elements 44 5.2.2 Ceremonial Paraphernalia and miniature empire 46 5.3 Discussion 49 Chapter 6 Conclusion: Domesticating objects into local political metaphor 52 List of Illustrations 56 Illustration credits 69 Bibliography 71 2 Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Background In the 18th century, the global circulation of material culture followed by local transformations and adaptations had become common. -

Redefining an Imperial Collection: Problems of Modern Impositions and Interpretations

Redefining an imperial collection: problems of modern impositions and interpretations Nicole T.C. Chiang Introduction In 1924, when Aisin Gioro Puyi, the last emperor of China, was driven out of the imperial palaces, the Republican government formed the Committee for the Disposition of the Qing Imperial Possessions and took a comprehensive inventory of the objects in the Forbidden City.1 According to the committee’s twenty-eight volumes of reports, which were first published in 1925, the Qing court had left more than one million objects including bronzes, jades, ceramics paintings, calligraphy, enamel wares, lacquer wares and many other miscellaneous articles.2 Although many objects were accumulated by successive Qing rulers, it was the Qianlong emperor who was most responsible for the formation of the former palace riches. The Qianlong emperor came to the throne in 1736 at the age of twenty-five as the sixth emperor of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1644-1911) and abdicated voluntarily sixty years later as a filial act in order not to reign longer than his grandfather, the Kangxi emperor (r. 1662-1722). His reign witnessed the most prosperous time of the Qing dynasty as the economy flourished, the population grew and the territory expanded. In the heyday of the dynasty, his court amassed numerous cultural riches from all over China and beyond. The huge span of objects gathered together during the reign of the Qianlong emperor has deeply influenced the present understanding of the history of Chinese art. It has been pointed out that ‘surviving into museum collections to this day, the enormous store of cultural riches amassed by the Qianlong emperor has sometimes come to seem as if it is Chinese culture, and the material excluded by him has been correspondingly marginalised, or has not been preserved.’3 The extant objects from 1 Pinyin romanisation is used in this paper for Chinese unless when citing secondary sources which use other methods of Chinese romanisation. -

4 Piecing Shards Together

4 Piecing Shards Together The Uses and Manufacturing of Imperial Porcelain Guangyao Wang Abstract The imperial manufacture of porcelain in the Qing dynasty was always related to the broad state economy and politics, especially ritual. As has been revealed in administrative regulations and raw material sup- ply, porcelain production seemed to be an independent operation like other court art production. However, as evidence regarding managerial personnel, finance, quality control, and design shows, the technology for producing porcelain was integral to other material production at court. Thus, multiple productive processes were interdependent and they influenced each other. The productive processes and products of court art showcase the character of monarchical industry. Keywords: Imperial Manufactory of Porcelain, ritual vessel, porcelain supervision, labour Tang Ying 唐英 (1682-1756), the chief supervisor of the Imperial Ceramic Manufactory (Yuyaochang 御窯厰), once remarked that, ‘Although ceramic production is a minor concern, it is of relevance to the affairs of the state’ (tao sui xishi, guan hu guozheng 陶 雖 細 事 ,關 乎 國 政 ).1 Referring to this statement, many researchers have exaggerated the importance of imperial porcelain,2 or focused only on its political significance, at the expense 1 ‘Ciwu shiyi shiyu gao xu 瓷務事宜示諭稿序 (Tang Ying’s Preface to the Draft Advise on Ceramic Affairs)’, in Tang Ying 唐英, Tang Ying dutao wendang 唐英督陶文檔, ed. Zhang Faying 張發頴 (Beijing: Xueyuan chubanshe, 2012), 13. Tang Ying uses the word ‘ceramics’ (tao 陶) here to refer broadly to any fired clay. His quote indirectly refers to a quotation from the Chunqiu Zuo zhuan zhushu 春秋左傳注疏. -

Qiu Ying's Relationship with the Literati Society and the Market

!1 The Becoming of a Master: Qiu Ying’s Relationship with the Literati Society and the Market Leiden University MA Thesis of Asian Studies 60EC (History, Art, and Culture of Asia) s1822993 Chun Wei Chiang Supervised by Prof. Fan Lin Second Reader: Anne Gerritsen !2 Introduction 3 Literary Review 3 Research Question 4 Structure 4 Qiu Ying’s Style 5 Qiu Ying in the Literati Society 16 Qiu Ying and the Market 26 Conclusion 36 List of Illustrations 38 Bibliography (Primary) 40 Bibliography (Secondary) 42 !3 Introduction Qiu Ying 仇英 (1494-1552) is one of a kind and a mystery in Chinese art history due to the fact that Qiu Ying himself did not leave any detailed source of writing about his life and work. However, this issue has not affected the mass popularity of his works from time to time. He is considered one of the most successful professional painters in Chinese art history, and was one of the most beloved painters during the Ming dynasty. Not to mention quite a number of exhibitions and retrospectives of his paintings were held in China and Taiwan in recent years. Literary Review Even though Qiu Ying is one of the fundamental painters in the art history of China, only few scholars have devoted themselves to studies and discussions that try to reveal his puzzled archival background. Ellen Johnston Laing is one of the few art historians who has paid great attention to the artistic career of Qiu Ying in a social aspect regarding his relationships with his major patrons. In her article “Sixteenth-Century Patterns of Art Patronage: Qiu Ying and the Xiang Family”, she discusses about Qiu Ying’s long term relationship with one of his major patrons Xiang Yuanbian 項元汴 (1525-1590) and others in the Xiang family1.