An Abstract of the Thesis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Okie Women and Dust Bowl Memories

Sarah Lawrence College DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence Women's History Theses Women’s History Graduate Program 5-2015 Radical Genealogies: Okie Women and Dust Bowl Memories Carly Fox Sarah Lawrence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/womenshistory_etd Part of the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Fox, Carly, "Radical Genealogies: Okie Women and Dust Bowl Memories" (2015). Women's History Theses. 1. https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/womenshistory_etd/1 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Women’s History Graduate Program at DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's History Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Radical Genealogies: Okie Women and Dust Bowl Memories Carly Fox Submitted in Partial Completion of the Master of Arts Degree at Sarah Lawrence College May 2015 CONTENTS Abstract i Dedication ii Acknowledgments iii Preface iv List of Figures vii List of Abbreviations viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1. “The Worst Red-Headed Agitator in Tulare County”: The Life of Lillie Dunn 13 Chapter 2. A Song To The Plains: Sanora Babb’s Whose Names are Unknown 32 Chapter 3. Pick Up Your Name: The Poetry of Wilma Elizabeth McDaniel 54 Conclusion 71 Figures 73 Bibliography 76 i ABSTRACT This paper complicates the existing historiography about dust bowl migrants, often known as Okies, in Depression-era California. Okies, the dominant narrative goes, failed to organize in the ways that Mexican farm workers did, developed little connection with Mexican or Filipino farm workers, and clung to traditional gender roles that valorized the male breadwinner. -

Guide to the Firebrand Books Records, 1984-2000 Collection Number: 7670

Guide to the Firebrand Books Records, 1984-2000 Collection Number: 7670 Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections Cornell University Library Contact Information: Compiled Date EAD encoding: Division of Rare and Manuscript by: completed: Peter Martinez, April, Collections Brenda Marston March 15, 2001 2002 2B Carl A. Kroch Library Cornell University Ithaca, NY 14853 (607) 255-3530 Fax: (607) 255-9524 [email protected] http://rmc.library.cornell.edu © 2002 Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library DESCRIPTIVE SUMMARY Title: Firebrand Books records, 1984-2000 Collection Number: 7670 Creator: Firebrand Books (Ithaca, N.Y.). Quantity: 58 cubic ft. Forms of Material: Manuscripts, financial records, personnel records, computer files, ephemera. Repository: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library Abstract: Files on published books; rejection letters; invoices; distributors' reports; vendor files; files on conferences and events the publisher attended; file from publisher's service on the Advisory Committee to the Human Sexuality Collection, 1991; mailing list; lists of Firebrand employees and interns; summary of financial donations to Firebrand; Firebrand's web site; and posters that decorated the office. Language: Collection material in English ORGANIZATIONAL HISTORY From 1984 to 2000, Firebrand Books published exceptional literary fiction, nonfiction, and poetry on lesbian and feminist themes. Publisher Nancy Bereano won the Publisher's Service Award at the "Lammy" or Lambda Literary -

Conference Calendar: 2014 CCCC

Conference Calendar: 2014 CCCC Wednesday, March 19 Registration and Information 8:00 a.m..–6:00 p.m. Select Meetings and Other Events – various times Full-Day Workshops 9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. Half-Day Workshops 9:00 a.m.–12:30 p.m. Half-Day Workshops 1:30 p.m.–5:00 p.m. Newcomers’ Orientation 5:15 p.m.–6:15 p.m. Thursday, March 20 Newcomers’ Coffee Hour 7:30 a.m.–8:15 a.m. Registration and Information 8:00 a.m.–6:00 p.m. Opening General Session 8:30 a.m.–10:00 a.m. Exhibit Hall Open 10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. A Sessions 10:30 a.m.–11:45 a.m. B Sessions 12:15 p.m.–1:30 p.m. C Sessions 1:45 p.m.–3:00 p.m. D Sessions 3:15 p.m.–4:30 p.m. E Sessions 4:45 p.m.–6:00 p.m. Scholars for the Dream 6:00 p.m.–7:00 p.m. Special Interest Groups 6:30 p.m.–7:30 p.m. Friday, March 21 Registration and Information 8:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. Exhibit Hall Open 9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. F Sessions 8:00 a.m.–9:15 a.m. G Sessions 9:30 a.m.–10:45 a.m. H Sessions 11:00 a.m.–12:15 p.m. I Sessions 12:30 p.m.–1:45 p.m. J Sessions 2:00 p.m.–3:15 p.m. -

William Stafford

A Newsletter For Poets & Poetry Volume 11, Issue 3 - December 2006 Photo/Kit Stafford Board of Trustees Chair: Shelley Reece The Portland Tim Barnes Portland 2007 Elizabeth Barton Vancouver Patricia Carver Lake Oswego WILLIAM Don Colburn Portland STAFFORD Martha Gatchell Drain Sulima Malzin King City BIRTHDAY Paulann Petersen Portland EVENTS Dennis Schmidling Lake Oswego Helen Schmidling Lake Oswego � Joseph Soldati Portland Readings and Ann Staley Corvallis Celebrations Rich Wandschneider Enterprise Around the Nancy Winklesky Oregon City Photo/Estate of William Stafford Country Patty Wixon Ashland After side-stepping a lynch-mob for being a pacifist during World War II, William Stafford takes up his guitar for reconciliation. Sharon Wood Wortman Portland National Advisors: Join Us As We Celebrate the Spirit of William Stafford Marvin Bell Robert Bly Each year, the Friends of William Stafford rolls out members of the audience are invited to read their own Kurt Brown the red carpet to celebrate the late poet’s birthday favorite Stafford poem or share a memory. If you are Lucille Clifton (January 17, 1914) with a full month of Birthday new to the poetry of William Stafford, you may just James DePreist Celebration Readings. These events are held in enjoy hearing it for the first time. You can also learn Donald Hall communities throughout the country, and each more about us and sign up for a free newsletter. We Maxine Kumin year more are added. Free and open to the public, look forward to sharing this time with you and welcome Li-Young Lee they offer old friends and new a chance to share in your feedback at www. -

Nepali Women Nepali Women

her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/11/09 12:04 PM Page C1 PINK PANTY THE WOMEN’S FALL OF PROTEST MOVEMENT PATRIARCHY INDIA PUB ATTACK IS THERE ROOM ANGERS WOMEN FOR MEN? IMMINENT WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS Fall 2009 Vol. 23 No. 2 Made in Canada AFGHANAFGHAN WOMENWOMEN STAND STRONG AGAINST SHIA LALAWW NEPALINEPALI WOMENWOMEN FIGHTFIGHT FORFOR CONSTITUTIONALCONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTSRIGHTS $6.75 Canada/US Publications Mail Agreement No. 40008866; PAP Registration No. 07944 Return Undeliverable Addresses to: PO Box 128, Winnipeg, MB R3C 2G1 Canada Display until December 15, 2009 her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/10/09 1:03 PM Page C2 Joss Maclennan Design, CEP Local 591-G Joss Maclennan Design, CEP Local 591-G CAWCAW womenwomen WeWe marchmarch forfor equality. equality. WeWe speakspeak outout for for justice. justice. We fight for change. We fight for change. For more information on women’s Forissues more and information rights please on visit women’s issueswww.caw.ca/women and rights please visit www.caw.ca/women CAW Full Sum-09.indd 1 28/05/09 5:19 PM her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/11/09 12:05 PM Page 1 FALL 2009 / VOLUME 23 NO. 2 news THE MOTHER OF ALL MUSEUMS 6 by Janet Nicol TEL AVIV SHOOTING IGNITES GAY RIGHTS 7 by Idit Cohen TIANANMEN MOTHERS REFUSE TO FORGET 22: Yvette Nolan 8 by Janet Nicol NEPALI WOMEN DEMAND EQUALITY 9 by Chelsea Jones 12 CAMPAIGN UPDATES PARENTING BILL WOULD ERODE RIGHTS 13 by Pamela Cross features IS FEMINISM MEN’S WORK, TOO? 16 It’s not called the women’s movement for nothing. -

Samhita Mukhopadhyay and Jaclyn Friedman Take the Theory to the Next Level

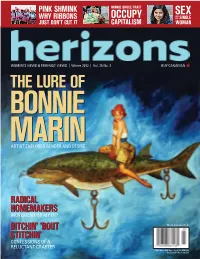

PINK SHMINK MINNIE BRUCE PRATT SEX AND WHY RIBBONS OCCUPY THE SINGLE JUST DON’T CUT IT CAPITALISM WOMAN WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS | Winter 2012 | Vol. 25 No. 3 BUY CANADIAN THETHE LURELURE OFOF BONNIEBONNIE MARINMARIN ARTIST EXPLORES GENDER AND DESIRE RADICAL HOMEMAKERS MOVEMENT OR MYTH? BITCHIN’ ’BOUT $6.75 Canada/U.S. STITCHIN’ CONFESSIONS OF A RELUCTANT CRAFTER Publications Mail Agreement No. 40008866; Display until March 30, 2012 CAW Full (bleed) Win-12.indd 1 11-11-28 2:03 PM WINTER 2012 / VOLUME 25 NO. 3 news SEEING RED OVER PINK . 6 by Amanda Le Rougetel CAMPAIGN UPDATES . 8 THE POET VS. THE PROFITEERS AN INTERVIEW WITH MINNIE BRUCE PRATT . 11 by Joy Parks 11 features CONFESSIONS OF A RELUCTANT CRAFTER . .14 The knitting trend has hit Canada by storm. So what’s a feminist to do: Join the rebel fibre movement or cast dire warnings that women will soon be barefoot in the kitchen? by Deborah Ostrovsky BASTARDS AND BULLIES . .20 Dorothy Palmer’s debut novel, When Fenelon Falls, features Jordan, a young girl who is adopted and disabled. The protagonist reflects some of Palmer’s experiences about what it is like to be adopted and disabled. by Niranjana Iyer THE LURE OF BONNIE MARIN: LESSONS IN TRANSGRESSIONS . .24 Visual artist Bonnie Marin freely mixes gender, race and even species in erotic environments that are part middle class 1950s normalcy and part spectacles of perversity. 14 by Shawna Dempsey HOW FEMINISM CAN IMPROVE YOUR SEX LIFE . .28 Two new books about sex and politics paint a provocative picture of feminist dating 45 years after the personal was declared to be political. -

Narrating the Nation of Palestine by Nuzhat Abbas

SPECIAL OFFER FOR CONFERENCE DELEGATES See inside for details • Canada $5.95/US $5.95 • Vol. 16 No.4 • Spring 2003 WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS NARRATINGNARRATING THETHE NATIONNATION OFOF PALESTINEPALESTINE AN INTERVIEW WITH NAHLA ABDO WHYWHY DODO LESBIANSLESBIANS BATTER?BATTER? JANICE RISTOCK WANTS TO KNOW THETHE HEARTHEART DOESDOES NOTNOT BENDBEND A CONVERSATION WITH MAKEDA SILVERA NAC NAC. Who’s There? Lisa B. Rundle: Marshalling in the Third Wave Pump up the Volume: Veda Hille, Afua Cooper, Jorane Made in Canada in Made table of contents SPRING 2003 / VOLUME 16 NO. 4 FEATURES NARRATING THE NATION 18 OF PALESTINE Arab feminist Nahla Abdo has written extensively about women and military confrontation and is the founder of a gender research unit within a mental health program in Gaza. A sociology professor at Carleton University, Ms Abdo talks to Herizons about the PLO, Israel, Palestinian women and about her upcoming book, Sexuality, Citizenship and the Nation State: Experiences of Palestinian Women. by Nuzhat Abbas IN CONVERSATION WITH 23 MAKEDA SILVERA Toronto author Makeda Silvera discusses mother- hood, poverty, colonialism and the creative process with author Elizabeth Ruth. “I’ve always questioned the imperial culture’s view of motherhood: mothers are virtuous, mothers are asexual…” by Elizabeth Ruth WHY DO LESBIANS Page 26: Janice Ristock 26 BATTER? A decade ago, Janice Ristock and some colleagues produced a booklet on violence in lesbian relation- NEWS ships. Now the Winnipeg researcher has written a groundbreaking book on the issue. VILLAGERS JOIN CAMPAIGN by Helen Fallding 6 AGAINST FGM A Senegalese women’s organization called Tostan, which means ‘breakthrough’ in the Wolof language, ARTS & LIT sponsors education programs that have influenced the decision of 708 villages to make public declara- CAN LIT tions to abandon the generations-old practice of 32 FICTION female genital mutilation. -

History 600: Public Intellectuals in the US Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Office

Hannah Arendt W.E.B. DuBois Noam Chomsky History 600: Public Intellectuals in the U.S. Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Lecturer: Ronit Stahl Class Meetings: Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 M 11 a.m.-1 p.m. email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Room: Mosse Hum. 5257 Prof. RR’s Office Hours: R.S.’s Office Hours: T 3- M 9 a.m.-11a.m. 5 p.m. This course is designed for students interested in exploring the life of the mind in the twentieth-century United States. Specifically, we will examine the life of particular minds— intellectuals of different political, moral, and social persuasions and sensibilities, who have played prominent roles in American public life over the course of the last century. Despite the common conception of American culture as profoundly anti-intellectual, we will evaluate how professional thinkers and writers have indeed been forces in American society. Our aim is to investigate the contested meaning, role, and place of the intellectual in a democratic, capitalist culture. We will also examine the cultural conditions, academic and governmental institutions, and the media for the dissemination of ideas, which have both fostered and inhibited intellectual production and exchange. Roughly the first third of the semester will be devoted to reading studies in U.S. and comparative intellectual history, the sociology of knowledge, and critical social theory. In addition, students will explore the varieties of public intellectual life by becoming familiarized with a wide array of prominent American philosophers, political and social theorists, scientists, novelists, artists, and activists. -

The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism by Cassie

#TrendingFeminism: The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism by Cassie Clark B.A. in English and Theatre, May 2007, St. Olaf College A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 17, 2015 Thesis directed by Todd Ramlow Adjunct Professor of Women’s Studies This work is dedicated to my grandfather, who, upon being told that I was planning to attend graduate school, responded, “Good, you should have more education than your father.” ii The author wishes to acknowledge Dr. Todd Ramlow for his expertise, knowledge, and encouragement. She also wishes to acknowledge Dr. Alexander Dent for his invaluable guidance regarding the performance of media and digital technologies. iii Abstract of Thesis #TrendingFeminism: The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism As the use of online platforms such as social networking sites, also known as social media, and blogs grew in popularity, feminists began to embrace digital media as a significant space for activism. Digital feminist activism is a new iteration of feminist activism, offering new tools and tactics for feminists to utilize to spread awareness, disseminate information, and mobilize constituents. In this paper I examine the intent, usefulness, and potential impact of digital feminist activism in the United States by analyzing key examples of social movements conducted via digital media. These analyses not only provide useful examples of a variety of digital feminist efforts, they also highlight strengths and weaknesses in each campaign with the aim of improving the impact of future digital feminist campaigns. -

Presentations Introduction Recent Feminist De

Beyond the Generational Line: An Exploration of Feminist Online Sites and Self-(Re)presentations Yi-lin Yu National Ilan University, Taiwan Abstract This article deals with the feminist generation issue by tracing the transition from generational to non-generational thinking in recent feminist discourse on third-wave feminism. Informed by certain feminist recommendations of affording alternative paradigms in place of the oceanic wave metaphor to describe the rela- tionships between different feminists, this study offers the insights gained from an investigation with three feminist online sites, The F Word, Eminism, and Guerrilla Girls, in which these online feminists have participated in building up a third wave consciousness or a third space site through their engagement in (re)presenting their feminist selves and identities. In developing a both/and third wave con- sciousness, these online feminists have bypassed the dualistic understanding of sec- ond and third wave feminism and reached a cross-generational commonality of adhering to feminist ideology and coalition in cyberspace as a third space. Through a content analysis of their online feminist self-(re)presentations, this pa- per concludes by arguing that they have not only reformulated the concept of third wave feminism but also worked toward a new configuration of third space narratives and subjectivities that sheds light on contemporary feminist thinking about feminist genealogy and history. Key words third-wave feminism, feminist generation, feminist online sites, self-(re)presentation Introduction Recent feminist development of third-wave discourses has been bom- barded with a conundrum regarding generational debates. Although 54 ❙ Yi-lin Yu some feminist scholars are preoccupied with using familial metaphors to depict different feminist generations, others have called forth a rethink- ing of the topic in non-generational terms. -

Barbara Grier--Naiad Press Collection

BARBARA GRIER—NAIAD PRESS COLLECTION 1956-1999 Collection number: GLC 30 The James C. Hormel Gay and Lesbian Center San Francisco Public Library 2003 Barbara Grier—Naiad Press Collection GLC 30 p. 2 Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction p. 3-4 Biography and Corporate History p. 5-6 Scope and Content p. 6 Series Descriptions p. 7-10 Container Listing p. 11-64 Series 1: Naiad Press Correspondence, 1971-1994 p. 11-19 Series 2: Naiad Press Author Files, 1972-1999 p. 20-30 Series 3: Naiad Press Publications, 1975-1994 p. 31-32 Series 4: Naiad Press Subject Files, 1973-1994 p. 33-34 Series 5: Grier Correspondence, 1956-1992 p. 35-39 Series 6: Grier Manuscripts, 1958-1989 p. 40 Series 7: Grier Subject Files, 1965-1990 p. 41-42 Series 8: Works by Others, 1930s-1990s p. 43-46 a. Printed Works by Others, 1930s-1990s p. 43 b. Manuscripts by Others, 1960-1991 p. 43-46 Series 9: Audio-Visual Material, 1983-1990 p. 47-53 Series 10: Memorabilia p. 54-64 Barbara Grier—Naiad Press Collection GLC 30 p. 3 Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library INTRODUCTION Provenance The Barbara Grier—Naiad Press Collection was donated to the San Francisco Public Library by the Library Foundation of San Francisco in June 1992. Funding Funding for the processing was provided by a grant from the Library Foundation of San Francisco. Access The collection is open for research and available in the San Francisco History Center on the 6th Floor of the Main Library. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre.