History 600: Public Intellectuals in the US Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Office

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Okie Women and Dust Bowl Memories

Sarah Lawrence College DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence Women's History Theses Women’s History Graduate Program 5-2015 Radical Genealogies: Okie Women and Dust Bowl Memories Carly Fox Sarah Lawrence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/womenshistory_etd Part of the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Fox, Carly, "Radical Genealogies: Okie Women and Dust Bowl Memories" (2015). Women's History Theses. 1. https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/womenshistory_etd/1 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Women’s History Graduate Program at DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's History Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Radical Genealogies: Okie Women and Dust Bowl Memories Carly Fox Submitted in Partial Completion of the Master of Arts Degree at Sarah Lawrence College May 2015 CONTENTS Abstract i Dedication ii Acknowledgments iii Preface iv List of Figures vii List of Abbreviations viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1. “The Worst Red-Headed Agitator in Tulare County”: The Life of Lillie Dunn 13 Chapter 2. A Song To The Plains: Sanora Babb’s Whose Names are Unknown 32 Chapter 3. Pick Up Your Name: The Poetry of Wilma Elizabeth McDaniel 54 Conclusion 71 Figures 73 Bibliography 76 i ABSTRACT This paper complicates the existing historiography about dust bowl migrants, often known as Okies, in Depression-era California. Okies, the dominant narrative goes, failed to organize in the ways that Mexican farm workers did, developed little connection with Mexican or Filipino farm workers, and clung to traditional gender roles that valorized the male breadwinner. -

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

Teaching to Transgress: Education As the Practice of Freedom Would Be a Book of Essays Mostly Directed to Teachers

Teaching to Transgress This page intentionally left blank Teaching to Transgress Education as the Practice of Freedom bell hooks Routledge New York London Published in 1994 by Published in Great Britain by Routledge Routledge Taylor & Francis Group Taylor & Francis Group 711 Third Avenue 2 Park Square New York, NY 10017 Milton Park, Abingdon Oxon OX14 4RN Copyright © 1994 Gloria Watkins All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data hooks, bell. Teaching to transgress : education as the practice of freedom / bell hooks p. cm. Includes index ISBN 0-415-90807-8 — ISBN 0-415-90808-6 (pbk.) 1. Critical pedagogy. 2. Critical thinking—Study and teaching. 3. Feminism and education. 4. Teaching. I. Title. LC196.H66 1994 370.11 '5—dc20 94-26248 CIP to all my students, especially to LaRon who dances with angels in gratitude for all the times we start over—begin again— renew our joy in learning. “. to begin always anew, to make, to reconstruct, and to not spoil, to refuse to bureaucratize the mind, to understand and to live life as a process—live to become ...” —Paulo Freire This page intentionally left blank Contents Introduction I Teaching to Transgress 1 Engaged Pedagogy 13 2 A Revolution of Values 23 The Promise of Multicultural -

Conference Calendar: 2014 CCCC

Conference Calendar: 2014 CCCC Wednesday, March 19 Registration and Information 8:00 a.m..–6:00 p.m. Select Meetings and Other Events – various times Full-Day Workshops 9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. Half-Day Workshops 9:00 a.m.–12:30 p.m. Half-Day Workshops 1:30 p.m.–5:00 p.m. Newcomers’ Orientation 5:15 p.m.–6:15 p.m. Thursday, March 20 Newcomers’ Coffee Hour 7:30 a.m.–8:15 a.m. Registration and Information 8:00 a.m.–6:00 p.m. Opening General Session 8:30 a.m.–10:00 a.m. Exhibit Hall Open 10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. A Sessions 10:30 a.m.–11:45 a.m. B Sessions 12:15 p.m.–1:30 p.m. C Sessions 1:45 p.m.–3:00 p.m. D Sessions 3:15 p.m.–4:30 p.m. E Sessions 4:45 p.m.–6:00 p.m. Scholars for the Dream 6:00 p.m.–7:00 p.m. Special Interest Groups 6:30 p.m.–7:30 p.m. Friday, March 21 Registration and Information 8:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. Exhibit Hall Open 9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. F Sessions 8:00 a.m.–9:15 a.m. G Sessions 9:30 a.m.–10:45 a.m. H Sessions 11:00 a.m.–12:15 p.m. I Sessions 12:30 p.m.–1:45 p.m. J Sessions 2:00 p.m.–3:15 p.m. -

Selected Resources for Understanding Racism

Selected Resources for Understanding Racism The 21st century has witnessed an explosion of efforts – in literature, art, movies, television, and other forms of communication—to explore and understand racism in all of its many forms, as well as a new appreciation of similar works from the 20th century. For those interested in updating and deepening their understanding of racism in America today, the Anti-Racism Group of Western Presbyterian Church has collaborated with the NCP MCC Race and Reconciliation Team to put together an annotated sampling of these works as a guide for individual efforts at self-development. The list is not definitive or all-inclusive. Rather, it is intended to serve as a convenient reference for those who wish to begin or continue their journey towards a greater comprehension of American racism. February 2020 Contemporary Alexander, Michelle. 2010. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. Written by a civil rights litigator, this book discusses race-related issues specific to African-American males and mass incarceration in the United States. The central premise is that "mass incarceration is, metaphorically, the New Jim Crow". Anderson, Carol. 2017. White Rage. From the Civil War to our combustible present, White Rage reframes our continuing conversation about race, chronicling the powerful forces opposed to black progress in America. Asch, Chris Myers and Musgrove, George Derek. 2017. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation's Capital. A richly researched and clearly written analysis of the history of racism in Washington, DC, from the 18th century to the present, and the efforts of people of color to claim a voice in local government decisionmaking. -

In Raisin in the Sun and Caroline, Or Change Theresa J

Spring 2006 127 “Consequences unforeseen . .” in Raisin in the Sun and Caroline, or Change Theresa J. May Out of the rack and ruin of our gangster death, The rape and rot of graft, and stealth, and lies, We the people must redeem The land, the mines, the plants, the rivers The mountains and the endless plain— All the stretch of these great green states— And make America again! —Langston Hughes (1938)1 Ecological sanity now requires social justice. —Barry Commoner (1971)2 We all live in the wake of hurricane Katrina. The implications and implicated deposit now on everyone’s doorsteps like the alluvial sludge from a mighty river burdened with the legacies of history. Past exploitations of land and people give rise to present litanies and lamentations. But for those whose faces, cries, and signs for help have been paraded across the media stream, the loss is ongoing, unrelenting, and disproportionately personal. These consequences were not unforeseen. (Witness, among other warnings, “Gone with the Water,” National Geographic, October 2004.)3 As officials tallied the dead, my attention was arrested by the lock step between systemic social injustice and environmental lunacy. The so-called natural disaster has exposed the un-natural systems of domination buried under decades of business as usual, unearthing a white supremacist patriarchy through which racism, poverty, and environmental degradation are inseparably institutionalized. Once again ecologically ill-conceived strategies for controlling, taming, and mining nature Theresa J. May is Assistant Professor of Theatre Arts at the University of Oregon. She has published articles on ecocriticism, performance studies, and feminism in the Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, On-Stage Studies, and Journal of American Drama and Theater Insight. -

Groundwork Humans & Nature Reader

Environmental Readings Volume 1: Humans Relationships With Nature Published by: Groundwork Education www.layinggroundwork.org Compiled & Edited by Jeff Wagner with help from Micaela Petrini, Caitlin McKimmy, Jason Shah, Parker Pflaum, Itzá Martinez de Eulate Lanza, Jhasmany Saavedra, & Dev Carey First Edition, June 2018 This work is comprised of articles and excerpts from numerous sources. Groundwork and the editors do not own the material or claim copyright or rights to this material, unless written by one of the editors. This work is distributed as a compilation of educational materials for the sole use as non-commercial educational material for educators. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free to edit and share this work in non-commercial ways. Any published derivative works must credit the original creator and maintain this same Creative Commons license. Please notify us of any derivative works or edits. Environmental Readings Volume 1: Human Relationships With Nature Published by Groundwork Education, compiled & edited by Jeff Wagner Skywoman Falling by Robin Wall Kimmerer .......................................................1 An alternative view: how to frame a relationship with the natural world that’s not just extractive and destructive. The Gospel of Consumption by Jeffrey Kaplan ....................................................4 What is the origin of our consumption-based society, and when did we make this choice as a people? Earthbound: On Solid Ground by bell hooks .......................................................9 “More than ever before in our nation’s history black folks must collectively renew our relationship to the earth…” Do we really love our land? by David James Duncan ..........................................11 What do people mean when they speak of “love of the land?” Most Americans claim to feel such a love. -

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture: Anarchy, the Beats and the Psychedelic Transformation of Consciousness By Ed D’Angelo Copyright © Ed D’Angelo 2019 A much shortened version of this paper appeared as “Anarchism and the Beats” in The Philosophy of the Beats, edited by Sharin Elkholy and published by University Press of Kentucky in 2012. 1 The postwar American counterculture was established by a small circle of so- called “beat” poets located primarily in New York and San Francisco in the late 1940s and 1950s. Were it not for the beats of the early postwar years there would have been no “hippies” in the 1960s. And in spite of the apparent differences between the hippies and the “punks,” were it not for the hippies and the beats, there would have been no punks in the 1970s or 80s, either. The beats not only anticipated nearly every aspect of hippy culture in the late 1940s and 1950s, but many of those who led the hippy movement in the 1960s such as Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg were themselves beat poets. By the 1970s Allen Ginsberg could be found with such icons of the early punk movement as Patty Smith and the Clash. The beat poet William Burroughs was a punk before there were “punks,” and was much loved by punks when there were. The beat poets, therefore, helped shape the culture of generations of Americans who grew up in the postwar years. But rarely if ever has the philosophy of the postwar American counterculture been seriously studied by philosophers. -

Dr. Lionel Trilling Jefferson Lecturer the Blakelock Problem

Humanities New York City, a sheaf of rolled-up canvases under his arm, while Blakelock bargained; as often as not, they’d return to the same dealers with the same pic tures just before closing, Blakelock desperate and willing to accept almost anything for his work. He was a self-taught artist, born and raised in New York City, who headed west after graduation from what is now the City University of New York, sketch ing his way across the plains to the coast, returning by way of Mexico, Panama, and the West Indies. At first he painted pictures in the Hudson River style— romantically colored panoramas identifiable with the locales he had visited. But as the years passed, the children came, and fame, fortune or even a minimal income eluded him, Blakelock started building on canvas a world of his own: dark scenes, heavy with overarching trees Dr. Lionel Trilling brooding over moonlit waters, highly romantic Indian Jefferson Lecturer encampments that never were. Bright colors left his palette, the hues of night dominated. Dr. Lionel Trilling will deliver the first Jefferson Lec Blakelock did build up a modest following of col ture in the Humanities before a distinguished au lectors, but in the 1870’s and 1880’s, $30 to $50 was dience at the National Academy of Sciences Audi a decent price for a sizable painting by an unknown, torium, 2101 Constitution Avenue Northwest, Wash and his fees never caught up with his expenses. Only ington, D. C. on Wednesday, April 26 at eight once did light break through: in 1883, the Toledo o ’clock. -

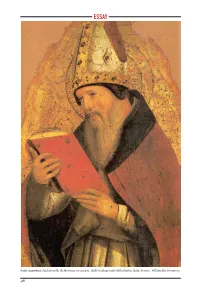

Saint Augustine, by Antonello De Messina, Circa 1472. Galleria Regionale Della Sicilia, Italy

ESSAY Caption?? Saint Augustine, by Antonello de Messina, circa 1472. Galleria Regionale della Sicilia, Italy. Source: Wikimedia Commons. 48 READING AUGUSTINE James Turner JoHnson ugustine’s influence runs deep and broad through Western Christian Adoctrine and ethics. This paper focuses on two particular examples of this influence: his thinking on political order and on just war. Augustine’s conception of political order and the Christian’s proper relation to it, developed most fully in his last and arguably most comprehensive theological work, The City of God, is central in both Catholic and mainline Protestant thinking on the political community and the proper exercise of government. Especially important in recent debate, the origins of the Christian idea of just war trace to Augustine. Exactly how Augustine has been read and understood on these topics, as well as others, has varied considerably depending on context, so the question in each and every context is how to read and understand Augustine. Paul Ramsey was right to insist, them as connected. When they fundamental problem for any in the process of developing are separated, one or another reading of Augustine on these his own understanding of just kind of distortion is the result. subjects. war, that in Christian thinking the idea of just war does not It is, of course, possible to ap- My discussion begins by exam- stand alone but is part of a com- proach either or both of these ining the use of Augustine by prehensive conception of good topics without taking account two prominent recent thinkers politics. This also describes of Augustine’s thinking or its on just war, Paul Ramsey and Augustine’s thinking. -

Lionel Trilling's Existential State

Lionel Trilling’s Existential State Michael Szalay Death is like justice is supposed to be. Ralph Ellison, Three Days Before the Shooting IN 1952, LIONEL TRILLING ANNOUNCED THAT “intellect has associated itself with power, per- haps as never before in history, and is now conceded to be in itself a kind of power.” He was de- scribing what would be his own associations: his personal papers are littered with missives from the stars of postwar politics. Senator James L. Buckley admires his contribution to American let- ters. Jacob J. Javits does the same. Daniel Patrick Moynihan praises him as “the nation’s leading literary critic.” First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy writes from the White House, thanking him for the collection of D. H. Lawrence stories and hoping to see him again soon. Three years later, President Lyndon Johnson sends a telegram asking Trilling to represent him at the funeral of T. S. Eliot. Politicians liked having Trilling around. He confirmed their noble sense of mission as often as they praised him.1 Trilling’s accommodating relation to power alienated many of his peers, like Irving Howe and C. Wright Mills, and later provoked condemnations from historians like Christopher Lasch and MICHAEL SZALAY teaches American literature and culture at UC, Irvine, and is the author of New Deal Modernism and The Hip Figure, forthcoming from Stanford University Press. He is co-editor of Stanford’s “Post*45” Book Series. 1 Trilling thought that the political establishment embraced intellectuals because it was “uneasy with itself” and eager “to apologize for its existence by a show of taste and sensitivity.” Trilling, “The Situation of the American Intellectual at the Present Time,” in The Moral Obligation to Be Intelligent, ed. -

Michael Harrington

Michael Harrington What Socialists Would Do in America If They Could L et's pose a far-reaching question, without socialist alternative. It is with this thought in pretending to answer it fully. What would mind that I undertake an attempt to define a happen in America if we were able to make it socialist policy for the (still unforeseeable) come to pass? How would we move beyond middle distance. First, I will try to outline the welfare state? What measures would be some of the general problems raised by such taken on the far side of liberal reform, yet well an imaginative definition of the future. Then, short of utopia? there will be a brief sketch of that possible These questions are not academic. In socialist future. And finally, I will try to relate Europe today there are democratic socialist these speculations to the immediate present, mass parties that are putting them on the since I am convinced that projecting what political agenda. In America there is, of should be must help us, here and now, in de- course, no major socialist movement, yet. But vising what can be. this society is more and more running up against the inherent limits of the welfare state. I: Some General Problems We can no longer live with the happy as- sumptions of '60s liberalism—that an endless, noninflationary growth would not only allow Capitalism is dying. It will not, however, us to finance social justice but to profit from it disappear on a given day, or in a given month as well.