An Argument for Intersectionality Originally, the Feminist Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radical Feminism and Its Major Socio-Religious Impact… 45 Radical Feminism and Its Major Socio-Religious Impact (A Critical Analysis from Islamic Perspective) Dr

Radical Feminism and its Major Socio-Religious Impact… 45 Radical Feminism and its Major Socio-Religious Impact (A Critical Analysis from Islamic Perspective) Dr. Riaz Ahmad Saeed Dr. Arshad Munir Leghari ** ABSTRACT Women’s rights and freedom is one of the most debated subjects and the flash point of contemporary world. Women maintain a significant place in the society catered to them not only by the modern world but also by religion. Yet, the clash between Islamic and western civilization is that they have defined different set of duties for them. Islam considers women an important participatory member of the society by assigning them inclusive role, specifying certain fields of work to them, given the vulnerability they might fall victim to. Contrarily, Western world allows women to opt any profession of their choice regardless of tangible threats they may encounter. Apparently, the modern approach seems more attractive and favorable, but actually this is not plausible from Islamic point of view. Intermingling, co-gathering and sexual attraction of male and female are creating serious difficulties and problems for both genders, especially for women. Women are currently running many movements for their security, rights and liberties under the umbrella of “Feminism”. Due to excess of freedom and lack of responsibility, a radical movement came into existence which was named as ‘Radical Feminism’. This feminist movement is affecting the unique status of women in the whole world, especially in the west. This study seeks to explore radical feminism and its major impact on socio-religious norms in addition to its critical analysis from an Islamic perspective. -

In Andrea Dworkin and Catharine Mackinnon

Dymock, Alex. 2018. Anti-communal, Anti-egalitarian, Anti-nurturing, Anti-loving: Sex and the ’Irredeemable’ in Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon. Paragraph, 41(3), pp. 349-363. ISSN 0264-8334 [Article] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/27778/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] Anticommunal, antiegalitarian, antinurturing, antiloving: sex and the ‘irredeemable’ in Dworkin and MacKinnon ALEX DYMOCK Abstract: The work of Andrea Dworkin and Catharine A. MacKinnon on sex and sexuality has often been posed as adversary to the development of queer theory. Leo Bersani, in particular, is critical of the normative ambitions of their work, which he sees firstly as trying to ‘redeem’ sex acts themselves, and secondly as advocating for sexuality as a site of potential for social transformation. In this article, I argue that this is a misreading of their work. Drawing on Dworkin’s wide body of writing, and the early Signs essays of MacKinnon, I suggest that their work makes no such case for sex or sexuality. Rather, by bringing their analysis into conversation with Halberstam’s recent work on ‘shadow feminism’, I contend that Dworkin and MacKinnon’s anti- social, anti-pastoral and distinctly anti-normative vision of sex and sexuality shares many of the same features of queer theory, ultimately advocating for sex as ‘irredeemable’. -

10 Tips for Working with Transgender Patients

Introduction to the transgender community MEDICAL PROTOCOLS The World Professional Association for Gender identity is our internal understanding of Transgender Health (WPATH) publishes our own gender. We all have a gender identity. Standards of Care for the treatment of The term “transgender” is used to describe people gender identity disorders, available at whose gender identity does not correspond to their www.wpath.org. These internationally rec- birth-assigned sex and/or the stereotypes asso- ognized protocols are flexible guidelines ciated with that sex. A transgender woman is a designed to help providers develop individ- woman who was assigned male at birth and has ualized treatment plans with their patients. 10 Tips for Working a female gender identity. A transgender man is a man who was assigned female at birth and has a Another resource is the Primary Care Proto- with Transgender male gender identity. col for Transgender Patient Care produced by Center of Excellence for Transgender Patients For many transgender individuals, the lack of con- Health at the University of California, San An information and resource publication gruity between their gender identity and their Francisco. You can view the treatment birth sex creates stress and anxiety that can lead protocols at www.transhealth.ucsf.edu/ for health care providers to severe depression, suicidal tendencies, and/or protocols. These protocols provide accu- increased risk for alcohol and drug dependency. rate, peer-reviewed medical guidance on Transitioning - the process that many transgen- transgender health care and are a resource der people undergo to bring their outward gender for providers and support staff to improve expression into alignment with their gender iden- treatment capabilities and access to care tity - is for many medically necessary treatment for transgender patients. -

The Radical Feminist Manifesto As Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, and Second Wave Resistance

Southern Journal of Communication ISSN: 1041-794X (Print) 1930-3203 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsjc20 The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance Kimber Charles Pearce To cite this article: Kimber Charles Pearce (1999) The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance, Southern Journal of Communication, 64:4, 307-315, DOI: 10.1080/10417949909373145 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949909373145 Published online: 01 Apr 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 578 View related articles Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsjc20 The Radical Feminist Manifesto as Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, And Second Wave Resistance Kimber Charles Pearce n June of 1968, self-styled feminist revolutionary Valerie Solanis discovered herself at the heart of a media spectacle after she shot pop artist Andy Warhol, whom she I accused of plagiarizing her ideas. While incarcerated for the attack, she penned the "S.C.U.M. Manifesto"—"The Society for Cutting Up Men." By doing so, Solanis appropriated the traditionally masculine manifesto genre, which had evolved from sov- ereign proclamations of the 1600s into a form of radical protest of the 1960s. Feminist appropriation of the manifesto genre can be traced as far back as the 1848 Seneca Falls Woman's Rights Convention, at which suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Coffin Mott, Martha Coffin, and Mary Ann McClintock parodied the Declara- tion of Independence with their "Declaration of Sentiments" (Campbell, 1989). -

Inconsistent Legal Treatment of Unwanted Sexual Advances: a Study of the Homosexual Advance Defense, Street Harassment, and Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

Inconsistent Legal Treatment of Unwanted Sexual Advances: A Study of the Homosexual Advance Defense, Street Harassment, and Sexual Harassment in the Workplace Kavita B. Ramakrishnant ABSTRACT In this Article, I contend that unwanted sexual advances on men are treated differently under the law than are unwanted sexual advances on women. I com- pare the legal conceptualization and redress of two of the most common types of unwanted sexual advances faced by women-street harassment and sexual ha- rassment in the workplace-with the legal treatment of unwanted sexual ad- vances on men as seen through the homosexual advance defense. I argue that the law recognizes certain advances on men as inappropriate enough to deserve legal recognition in the form of mitigation of murder charges while factually indistin- guishable advances on women are not even considered severe enough to rise to the level of a legally cognizable claim. Unwanted sexual advances on men do not receive the same level of scruti- ny as unwanted sexual advances on women. First, unwanted advances on men are often conclusively presumed to be unwanted and worthy of legal recognition, whereas unwanted advances on women are more rigorously subjected to a host of procedural and doctrinal barriers. Further, while one nonviolent same-sex ad- vance on a man may be sufficient to demonstrate provocation, there is currently no legal remedy that adequately addresses a nonviolent same-sex advance on a woman. Thus, a woman may not receive legal recognition for experiencing the t J.D., UCLA School of Law, 2009. B.A. University of Pennsylvania, 2004. -

Homophobia and Transphobia Illumination Project Curriculum

Homophobia and Transphobia Illumination Project Curriculum Andrew S. Forshee, Ph.D., Early Education & Family Studies Portland Community College Portland, Oregon INTRODUCTION Homophobia and transphobia are complicated topics that touch on core identity issues. Most people tend to conflate sexual orientation with gender identity, thus confusing two social distinctions. Understanding the differences between these concepts provides an opportunity to build personal knowledge, enhance skills in allyship, and effect positive social change. GROUND RULES (1015 minutes) Materials: chart paper, markers, tape. Due to the nature of the topic area, it is essential to develop ground rules for each student to follow. Ask students to offer some rules for participation in the postperformance workshop (i.e., what would help them participate to their fullest). Attempt to obtain a group consensus before adopting them as the official “social contract” of the group. Useful guidelines include the following (Bonner Curriculum, 2009; Hardiman, Jackson, & Griffin, 2007): Respect each viewpoint, opinion, and experience. Use “I” statements – avoid speaking in generalities. The conversations in the class are confidential (do not share information outside of class). Set own boundaries for sharing. Share air time. Listen respectfully. No blaming or scapegoating. Focus on own learning. Reference to PCC Student Rights and Responsibilities: http://www.pcc.edu/about/policy/studentrights/studentrights.pdf DEFINING THE CONCEPTS (see Appendix A for specific exercise) An active “toolkit” of terminology helps support the ongoing dialogue, questioning, and understanding about issues of homophobia and transphobia. Clear definitions also provide a context and platform for discussion. Homophobia: a psychological term originally developed by Weinberg (1973) to define an irrational hatred, anxiety, and or fear of homosexuality. -

Why Allowing Sex-Reassignment Surgery for Transgender Life Prisoners Facilitates Rehabilitation and Reconciliation

THE CAGED BIRD SINGS OF FREEDOM: WHY ALLOWING SEX-REASSIGNMENT SURGERY FOR TRANSGENDER LIFE PRISONERS FACILITATES REHABILITATION AND RECONCILIATION BY: ALEXANDER KIRKPATRICK* ABSTRACT In October 2015, California became the first state in U.S. history to implement guidelines for transgender state prisoners to petition for gender- affirming and sex-reassignment surgeries. These guidelines raise the question why California would authorize gender-affirming surgeries for prisoners serving life-sentences, yet struggle to implement laws to make the same surgeries more accessible to law-abiding citizens. While the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation ("CDCR") likely implemented the radical SRS policy to abide by Eighth Amendment protections for transgender inmates suffering from severe gender dysphoria-inmates to whom SRS coverage is medically necessary and constitutionally required-this Note outlines four alternative justifications * Class of 2017, University of Southern California Gould School of Law, B.A. Political Science, University of Colorado at Boulder. This Note is dedicated to my client, Amelia, who shared her vulnerable and inspiring story of incarceration, transition, and hope. Amelia is fighting for freedom every day in a California male institution. Thank you to my mentor and Note supervisor, Heidi Rummel, whom champions juvenile justice at the Post-Conviction Justice Project. She has exemplified the values of a lawyer I hope to become. Dear thanks to my partner, Mifa, who continues to challenge me to approach the world with empathy and fight for social justice. Thank you to my parents, brother, and aunt who have supported me every step of the way and showed me the value of storytelling. -

Trans* Politics and the Feminist Project: Revisiting the Politics of Recognition to Resolve Impasses

Politics and Governance (ISSN: 2183–2463) 2020, Volume 8, Issue 3, Pages 312–320 DOI: 10.17645/pag.v8i3.2825 Article Trans* Politics and the Feminist Project: Revisiting the Politics of Recognition to Resolve Impasses Zara Saeidzadeh * and Sofia Strid Department of Gender Studies, Örebro University, 702 81 Örebro, Sweden; E-Mails: [email protected] (Z.S.), [email protected] (S.S.) * Corresponding author Submitted: 24 January 2020 | Accepted: 7 August 2020 | Published: 18 September 2020 Abstract The debates on, in, and between feminist and trans* movements have been politically intense at best and aggressively hostile at worst. The key contestations have revolved around three issues: First, the question of who constitutes a woman; second, what constitute feminist interests; and third, how trans* politics intersects with feminist politics. Despite decades of debates and scholarship, these impasses remain unbroken. In this article, our aim is to work out a way through these impasses. We argue that all three types of contestations are deeply invested in notions of identity, and therefore dealt with in an identitarian way. This has not been constructive in resolving the antagonistic relationship between the trans* movement and feminism. We aim to disentangle the antagonism within anti-trans* feminist politics on the one hand, and trans* politics’ responses to that antagonism on the other. In so doing, we argue for a politics of status-based recognition (drawing on Fraser, 2000a, 2000b) instead of identity-based recognition, highlighting individuals’ specific needs in soci- ety rather than women’s common interests (drawing on Jónasdóttir, 1991), and conceptualising the intersections of the trans* movement and feminism as mutually shaping rather than as trans* as additive to the feminist project (drawing on Walby, 2007, and Walby, Armstrong, and Strid, 2012). -

Cp-Cajp-Inf 166-12 Eng.Pdf

PERMANENT COUNCIL OF THE OEA/Ser.G ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES CP/CAAP-INF. 166/12 23 April 2012 COMMITTEE ON JURIDICAL AND POLITICAL AFFAIRS Original: Spanish SEXUAL ORIENTATION, GENDER IDENTITY, AND GENDER EXPRESSION: KEY TERMS AND STANDARDS [Study prepared by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights "IACHR" pursuant to resolution AG/RES 2653 (XLI-O/11): Human Rights, Sexual Orientation, and Gender Identity] INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS COMISIÓN INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS COMISSÃO INTERAMERICANA DE DIREITOS HUMANOS COMISSION INTERAMÉRICAINE DES DROITS DE L’HOMME ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES WASHINGTON, D.C. 2 0 0 0 6 U.S.A. April 23, 2012 Re: Delivery of the study entitled “Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Gender Expression: Key Terms and Standards” Excellency: I have the honor to address Your Excellency on behalf of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and to attach the document entitled Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Gender Expression: Key Terms and Standards, which will be available in English and Spanish. This paper was prepared at the request of the OAS General Assembly, which, in resolution AG/RES. 2653 (XLI-O/11), asked the IACHR to prepare a study on “the legal implications and conceptual and terminological developments as regards sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression.” The IACHR remains at your disposal for any explanation or further details you may require. Accept, Excellency, renewed assurances of my highest consideration. Mario López Garelli on behalf of the Executive Secretary Her Excellency Ambassador María Isabel Salvador Permanent Representative of Ecuador Chair of the Committee on Juridical and Political Affairs Organization of American States Attachment SEXUAL ORIENTATION, GENDER IDENTITY AND GENDER EXPRESSION: SOME TERMINOLOGY AND RELEVANT STANDARDS I. -

Gender Identity • Expression

In New York City, it’s illegal to discriminate on the basis of gender identity and gender expression in the workplace, in public spaces, and in housing. The NYC Commission on Human Rights is committed to ensuring that transgender and gender non-conforming New Yorkers are treated with dignity and respect and without threat of discrimination or harassment. This means individuals GENDER GENDER have the right to: • Work and live free from discrimination IDENTITY EXPRESSION and harassment due to their gender One's internal, External representations of gender as identity/expression. deeply-held sense expressed through, for example, one's EXPRESSION • Use the bathroom or locker room most of one’s gender name, pronouns, clothing, haircut, consistent with their gender identity as male, female, behavior, voice, or body characteristics. • and/or expression without being or something else Society identifies these as masculine required to show “proof” of gender. entirely. A transgender and feminine, although what is • Be addressed with their preferred person is someone considered masculine and feminine pronouns and name without being whose gender identity changes over time and varies by culture. required to show “proof” of gender. does not match Many transgender people align their • Follow dress codes and grooming the sex they were gender expression with their gender standards consistent with their assigned at birth. identity, rather than the sex they were gender identity/expression. assigned at birth. Courtesy 101: IDENTITY GENDER • If you don't know what pronouns to use, ask. Be polite and respectful; if you use the wrong pronoun, apologize and move on. • Respect the terminology a transgender person uses to describe their identity. -

Nepali Women Nepali Women

her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/11/09 12:04 PM Page C1 PINK PANTY THE WOMEN’S FALL OF PROTEST MOVEMENT PATRIARCHY INDIA PUB ATTACK IS THERE ROOM ANGERS WOMEN FOR MEN? IMMINENT WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS Fall 2009 Vol. 23 No. 2 Made in Canada AFGHANAFGHAN WOMENWOMEN STAND STRONG AGAINST SHIA LALAWW NEPALINEPALI WOMENWOMEN FIGHTFIGHT FORFOR CONSTITUTIONALCONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTSRIGHTS $6.75 Canada/US Publications Mail Agreement No. 40008866; PAP Registration No. 07944 Return Undeliverable Addresses to: PO Box 128, Winnipeg, MB R3C 2G1 Canada Display until December 15, 2009 her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/10/09 1:03 PM Page C2 Joss Maclennan Design, CEP Local 591-G Joss Maclennan Design, CEP Local 591-G CAWCAW womenwomen WeWe marchmarch forfor equality. equality. WeWe speakspeak outout for for justice. justice. We fight for change. We fight for change. For more information on women’s Forissues more and information rights please on visit women’s issueswww.caw.ca/women and rights please visit www.caw.ca/women CAW Full Sum-09.indd 1 28/05/09 5:19 PM her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/11/09 12:05 PM Page 1 FALL 2009 / VOLUME 23 NO. 2 news THE MOTHER OF ALL MUSEUMS 6 by Janet Nicol TEL AVIV SHOOTING IGNITES GAY RIGHTS 7 by Idit Cohen TIANANMEN MOTHERS REFUSE TO FORGET 22: Yvette Nolan 8 by Janet Nicol NEPALI WOMEN DEMAND EQUALITY 9 by Chelsea Jones 12 CAMPAIGN UPDATES PARENTING BILL WOULD ERODE RIGHTS 13 by Pamela Cross features IS FEMINISM MEN’S WORK, TOO? 16 It’s not called the women’s movement for nothing. -

Samhita Mukhopadhyay and Jaclyn Friedman Take the Theory to the Next Level

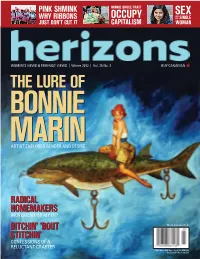

PINK SHMINK MINNIE BRUCE PRATT SEX AND WHY RIBBONS OCCUPY THE SINGLE JUST DON’T CUT IT CAPITALISM WOMAN WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS | Winter 2012 | Vol. 25 No. 3 BUY CANADIAN THETHE LURELURE OFOF BONNIEBONNIE MARINMARIN ARTIST EXPLORES GENDER AND DESIRE RADICAL HOMEMAKERS MOVEMENT OR MYTH? BITCHIN’ ’BOUT $6.75 Canada/U.S. STITCHIN’ CONFESSIONS OF A RELUCTANT CRAFTER Publications Mail Agreement No. 40008866; Display until March 30, 2012 CAW Full (bleed) Win-12.indd 1 11-11-28 2:03 PM WINTER 2012 / VOLUME 25 NO. 3 news SEEING RED OVER PINK . 6 by Amanda Le Rougetel CAMPAIGN UPDATES . 8 THE POET VS. THE PROFITEERS AN INTERVIEW WITH MINNIE BRUCE PRATT . 11 by Joy Parks 11 features CONFESSIONS OF A RELUCTANT CRAFTER . .14 The knitting trend has hit Canada by storm. So what’s a feminist to do: Join the rebel fibre movement or cast dire warnings that women will soon be barefoot in the kitchen? by Deborah Ostrovsky BASTARDS AND BULLIES . .20 Dorothy Palmer’s debut novel, When Fenelon Falls, features Jordan, a young girl who is adopted and disabled. The protagonist reflects some of Palmer’s experiences about what it is like to be adopted and disabled. by Niranjana Iyer THE LURE OF BONNIE MARIN: LESSONS IN TRANSGRESSIONS . .24 Visual artist Bonnie Marin freely mixes gender, race and even species in erotic environments that are part middle class 1950s normalcy and part spectacles of perversity. 14 by Shawna Dempsey HOW FEMINISM CAN IMPROVE YOUR SEX LIFE . .28 Two new books about sex and politics paint a provocative picture of feminist dating 45 years after the personal was declared to be political.