Presentations Introduction Recent Feminist De

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: an Argument for Remembering and Recitation

LEUSCHEN, KATHLEEN T., Ph.D. The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: An Argument for Remembering and Recitation. (2016) Directed by Dr. Nancy Myers. 169 pp. Protesting the 1968 Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, NJ, second-wave feminists targeted racism, militarism, excessive consumerism, and sexism. Yet nearly fifty years after this protest, popular memory recalls these activists as bra-burners— employing a widespread, derogatory image of feminist activists as trivial and laughably misguided. Contemporary academics, too, have critiqued second-wave feminism as a largely white, middle-class, and essentialist movement, dismissing second-wave practices in favor of more recent, more “progressive” waves of feminism. Following recent rhetorical scholarly investigations into public acts of remembering and forgetting, my dissertation project contests the derogatory characterizations of second-wave feminist activism. I use archival research on consciousness-raising groups to challenge the pejorative representations of these activists within academic and popular memory, and ultimately, to critique telic narratives of feminist progress. In my dissertation, I analyze a rich collection of archival documents— promotional materials, consciousness-raising guidelines, photographs, newsletters, and reflective essays—to demonstrate that consciousness-raising groups were collectives of women engaging in literacy practices—reading, writing, speaking, and listening—to make personal and political material and discursive change, between and across differences among women. As I demonstrate, consciousness-raising, the central practice of second-wave feminism across the 1960s and 1970s, developed out of a collective rhetorical theory that not only linked personal identity to political discourses, but also 1 linked the emotional to the rational in the production of knowledge. -

Wedlock Or Deadlock? : Feminists' Attemps to Engage Irrigation

Wedlock or deadlock? Feminists’ attempts to engage irrigation engineers Promotor: Prof. Linden F. Vincent, hoogleraar in Irrigatie en waterbouwkunde Wageningen Universiteit Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Prof. Dr. Patricia Howards, Wageningen Universiteit Prof. Dr. Pieter van der Zaag, IHE-UNESCO, Delft Prof. Dr. Cecile Jackson, University of East-Anglia, Norwich, UK Dr. Loes Schenk-Sandbergen, Universiteit van Amsterdam Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoeksschool CERES Wedlock or deadlock? Feminists’ attempts to engage irrigation engineers Margreet Z. Zwarteveen Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. Dr. M. J. Kropff, in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 6 juni 2006 des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula WEDLOCK OR DEADLOCK? FEMINISTS’ ATTEMPTS TO ENGAGE IRRIGATION ENGINEERS. Wageningen UR. Promotor: Vincent, L.F. Wageningen: Margreet Z. Zwarteveen, 2006. – p. 304. ISBN: 90-8504-398-0 Copyright © 2006, by Margreet Z. Zwarteveen, The Netherlands Contents Tables and figures ............................................................................................................9 Acronyms..........................................................................................................................10 Glossary............................................................................................................................11 Acknowledgments..........................................................................................................13 -

Nepali Women Nepali Women

her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/11/09 12:04 PM Page C1 PINK PANTY THE WOMEN’S FALL OF PROTEST MOVEMENT PATRIARCHY INDIA PUB ATTACK IS THERE ROOM ANGERS WOMEN FOR MEN? IMMINENT WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS Fall 2009 Vol. 23 No. 2 Made in Canada AFGHANAFGHAN WOMENWOMEN STAND STRONG AGAINST SHIA LALAWW NEPALINEPALI WOMENWOMEN FIGHTFIGHT FORFOR CONSTITUTIONALCONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTSRIGHTS $6.75 Canada/US Publications Mail Agreement No. 40008866; PAP Registration No. 07944 Return Undeliverable Addresses to: PO Box 128, Winnipeg, MB R3C 2G1 Canada Display until December 15, 2009 her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/10/09 1:03 PM Page C2 Joss Maclennan Design, CEP Local 591-G Joss Maclennan Design, CEP Local 591-G CAWCAW womenwomen WeWe marchmarch forfor equality. equality. WeWe speakspeak outout for for justice. justice. We fight for change. We fight for change. For more information on women’s Forissues more and information rights please on visit women’s issueswww.caw.ca/women and rights please visit www.caw.ca/women CAW Full Sum-09.indd 1 28/05/09 5:19 PM her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/11/09 12:05 PM Page 1 FALL 2009 / VOLUME 23 NO. 2 news THE MOTHER OF ALL MUSEUMS 6 by Janet Nicol TEL AVIV SHOOTING IGNITES GAY RIGHTS 7 by Idit Cohen TIANANMEN MOTHERS REFUSE TO FORGET 22: Yvette Nolan 8 by Janet Nicol NEPALI WOMEN DEMAND EQUALITY 9 by Chelsea Jones 12 CAMPAIGN UPDATES PARENTING BILL WOULD ERODE RIGHTS 13 by Pamela Cross features IS FEMINISM MEN’S WORK, TOO? 16 It’s not called the women’s movement for nothing. -

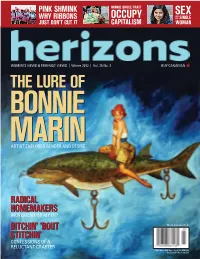

Samhita Mukhopadhyay and Jaclyn Friedman Take the Theory to the Next Level

PINK SHMINK MINNIE BRUCE PRATT SEX AND WHY RIBBONS OCCUPY THE SINGLE JUST DON’T CUT IT CAPITALISM WOMAN WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS | Winter 2012 | Vol. 25 No. 3 BUY CANADIAN THETHE LURELURE OFOF BONNIEBONNIE MARINMARIN ARTIST EXPLORES GENDER AND DESIRE RADICAL HOMEMAKERS MOVEMENT OR MYTH? BITCHIN’ ’BOUT $6.75 Canada/U.S. STITCHIN’ CONFESSIONS OF A RELUCTANT CRAFTER Publications Mail Agreement No. 40008866; Display until March 30, 2012 CAW Full (bleed) Win-12.indd 1 11-11-28 2:03 PM WINTER 2012 / VOLUME 25 NO. 3 news SEEING RED OVER PINK . 6 by Amanda Le Rougetel CAMPAIGN UPDATES . 8 THE POET VS. THE PROFITEERS AN INTERVIEW WITH MINNIE BRUCE PRATT . 11 by Joy Parks 11 features CONFESSIONS OF A RELUCTANT CRAFTER . .14 The knitting trend has hit Canada by storm. So what’s a feminist to do: Join the rebel fibre movement or cast dire warnings that women will soon be barefoot in the kitchen? by Deborah Ostrovsky BASTARDS AND BULLIES . .20 Dorothy Palmer’s debut novel, When Fenelon Falls, features Jordan, a young girl who is adopted and disabled. The protagonist reflects some of Palmer’s experiences about what it is like to be adopted and disabled. by Niranjana Iyer THE LURE OF BONNIE MARIN: LESSONS IN TRANSGRESSIONS . .24 Visual artist Bonnie Marin freely mixes gender, race and even species in erotic environments that are part middle class 1950s normalcy and part spectacles of perversity. 14 by Shawna Dempsey HOW FEMINISM CAN IMPROVE YOUR SEX LIFE . .28 Two new books about sex and politics paint a provocative picture of feminist dating 45 years after the personal was declared to be political. -

Narrating the Nation of Palestine by Nuzhat Abbas

SPECIAL OFFER FOR CONFERENCE DELEGATES See inside for details • Canada $5.95/US $5.95 • Vol. 16 No.4 • Spring 2003 WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS NARRATINGNARRATING THETHE NATIONNATION OFOF PALESTINEPALESTINE AN INTERVIEW WITH NAHLA ABDO WHYWHY DODO LESBIANSLESBIANS BATTER?BATTER? JANICE RISTOCK WANTS TO KNOW THETHE HEARTHEART DOESDOES NOTNOT BENDBEND A CONVERSATION WITH MAKEDA SILVERA NAC NAC. Who’s There? Lisa B. Rundle: Marshalling in the Third Wave Pump up the Volume: Veda Hille, Afua Cooper, Jorane Made in Canada in Made table of contents SPRING 2003 / VOLUME 16 NO. 4 FEATURES NARRATING THE NATION 18 OF PALESTINE Arab feminist Nahla Abdo has written extensively about women and military confrontation and is the founder of a gender research unit within a mental health program in Gaza. A sociology professor at Carleton University, Ms Abdo talks to Herizons about the PLO, Israel, Palestinian women and about her upcoming book, Sexuality, Citizenship and the Nation State: Experiences of Palestinian Women. by Nuzhat Abbas IN CONVERSATION WITH 23 MAKEDA SILVERA Toronto author Makeda Silvera discusses mother- hood, poverty, colonialism and the creative process with author Elizabeth Ruth. “I’ve always questioned the imperial culture’s view of motherhood: mothers are virtuous, mothers are asexual…” by Elizabeth Ruth WHY DO LESBIANS Page 26: Janice Ristock 26 BATTER? A decade ago, Janice Ristock and some colleagues produced a booklet on violence in lesbian relation- NEWS ships. Now the Winnipeg researcher has written a groundbreaking book on the issue. VILLAGERS JOIN CAMPAIGN by Helen Fallding 6 AGAINST FGM A Senegalese women’s organization called Tostan, which means ‘breakthrough’ in the Wolof language, ARTS & LIT sponsors education programs that have influenced the decision of 708 villages to make public declara- CAN LIT tions to abandon the generations-old practice of 32 FICTION female genital mutilation. -

Christina Hoff Sommers

A Conversation with CHRISTINA HOFF SOMMERS A resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and former philosophy professor, Christina Hoff Sommers is a thoughtful analyst and trenchant critic of radical feminism. In this conversation, Sommers and Kristol discuss how American feminism, once focused on practical questions such as equal opportunity in employment for women, instead became a radical ideology that questioned the reality of sex differences. Narrating her own experiences as a speaker on college campuses, Sommers explains how the radical feminism of today's universities stifles debate. Finally, Sommers explains a recent controversy in the video game community, which she defends from charges of sexism in a widely-publicized episode known as "GamerGate." On claims of a “rape epidemic” on campus, Sommers says: It’s the result of advocacy research. You can get very alarming findings if you’re willing to interview a non-representative sample of people and if you’re willing to include a lot of behavior most of us don’t think of as assault. If you just play with those, you can get an epidemic. Rape, like all crimes, is way down. It’s at I think a 41- year low. [Rape on campus] is not 1 in 4, or 1 in 5 women, but something like 1 in 50. Still too much. But not [an epidemic]. On the feminist denial of sex differences, Sommers says: Femininity and masculinity are real. Women tend to be more nurturing and risk-averse and have usually a richer emotional vocabulary. Men tend to be a little less explicit about their emotions. -

Feminism & Philosophy Vol.5 No.1

APA Newsletters Volume 05, Number 1 Fall 2005 NEWSLETTER ON FEMINISM AND PHILOSOPHY FROM THE EDITOR, SALLY J. SCHOLZ NEWS FROM THE COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN, ROSEMARIE TONG ARTICLES MARILYN FISCHER “Feminism and the Art of Interpretation: Or, Reading the First Wave to Think about the Second and Third Waves” JENNIFER PURVIS “A ‘Time’ for Change: Negotiating the Space of a Third Wave Political Moment” LAURIE CALHOUN “Feminism is a Humanism” LOUISE ANTONY “When is Philosophy Feminist?” ANN FERGUSON “Is Feminist Philosophy Still Philosophy?” OFELIA SCHUTTE “Feminist Ethics and Transnational Injustice: Two Methodological Suggestions” JEFFREY A. GAUTHIER “Feminism and Philosophy: Getting It and Getting It Right” SARA BEARDSWORTH “A French Feminism” © 2005 by The American Philosophical Association ISSN: 1067-9464 BOOK REVIEWS Robin Fiore and Hilde Lindemann Nelson: Recognition, Responsibility, and Rights: Feminist Ethics and Social Theory REVIEWED BY CHRISTINE M. KOGGEL Diana Tietjens Meyers: Being Yourself: Essays on Identity, Action, and Social Life REVIEWED BY CHERYL L. HUGHES Beth Kiyoko Jamieson: Real Choices: Feminism, Freedom, and the Limits of the Law REVIEWED BY ZAHRA MEGHANI Alan Soble: The Philosophy of Sex: Contemporary Readings REVIEWED BY KATHRYN J. NORLOCK Penny Florence: Sexed Universals in Contemporary Art REVIEWED BY TANYA M. LOUGHEAD CONTRIBUTORS ANNOUNCEMENTS APA NEWSLETTER ON Feminism and Philosophy Sally J. Scholz, Editor Fall 2005 Volume 05, Number 1 objective claims, Beardsworth demonstrates Kristeva’s ROM THE DITOR “maternal feminine” as “an experience that binds experience F E to experience” and refuses to be “turned into an abstraction.” Both reconfigure the ground of moral theory by highlighting the cultural bias or particularity encompassed in claims of Feminism, like philosophy, can be done in a variety of different objectivity or universality. -

The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism by Cassie

#TrendingFeminism: The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism by Cassie Clark B.A. in English and Theatre, May 2007, St. Olaf College A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 17, 2015 Thesis directed by Todd Ramlow Adjunct Professor of Women’s Studies This work is dedicated to my grandfather, who, upon being told that I was planning to attend graduate school, responded, “Good, you should have more education than your father.” ii The author wishes to acknowledge Dr. Todd Ramlow for his expertise, knowledge, and encouragement. She also wishes to acknowledge Dr. Alexander Dent for his invaluable guidance regarding the performance of media and digital technologies. iii Abstract of Thesis #TrendingFeminism: The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism As the use of online platforms such as social networking sites, also known as social media, and blogs grew in popularity, feminists began to embrace digital media as a significant space for activism. Digital feminist activism is a new iteration of feminist activism, offering new tools and tactics for feminists to utilize to spread awareness, disseminate information, and mobilize constituents. In this paper I examine the intent, usefulness, and potential impact of digital feminist activism in the United States by analyzing key examples of social movements conducted via digital media. These analyses not only provide useful examples of a variety of digital feminist efforts, they also highlight strengths and weaknesses in each campaign with the aim of improving the impact of future digital feminist campaigns. -

A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page Lyndsey S

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 2015 A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page Lyndsey S . Collins Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Collins, Lyndsey S ., "A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 2559. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd/2559 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr by Lyndsey S. Collins A Thesis Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sociology Lehigh University May 18, 2015 © 2015 Copyright (Lyndsey S. Collins) ii Thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Sociology. A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page Lyndsey Collins ____________________ Date Approved Dr. Jacqueline Krasas Dr. Yuping Zhang Dr. Nicola Tannenbaum iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis advisor, Dr. Jacqueline Krasas, who has provided me with invaluable insights, support, and encouragement throughout the entirety of this process. In addition, I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Nicola Tannenbaum -

Mainstream Feminism

Feminist movements and ideologies This collection of feminist buttons from a women's museum shows some messages from feminist movements. A variety of movements of feminist ideology have developed over the years. They vary in goals, strategies, and affiliations. They often overlap, and some feminists identify themselves with several branches of feminist thought. Groupings Judith Lorber distinguishes between three broad kinds of feminist discourses: gender reform feminisms, gender resistant feminisms, and gender revolution feminisms. In her typology, gender reform feminisms are rooted in the political philosophy of liberalism with its emphasis on individual rights. Gender resistant feminisms focus on specific behaviors and group dynamics through which women are kept in a subordinate position, even in subcultures which claim to support gender equality. Gender revolution feminisms seek to disrupt the social order through deconstructing its concepts and categories and analyzing the cultural reproduction of inequalities.[1] Movements and ideologies Mainstream feminism … "Mainstream feminism" as a general term identifies feminist ideologies and movements which do not fall into either the socialist or radical feminist camps. The mainstream feminist movement traditionally focused on political and legal reform, and has its roots in first- wave feminism and in the historical liberal feminism of the 19th and early- 20th centuries. In 2017, Angela Davis referred to mainstream feminism as "bourgeois feminism".[2] The term is today often used by essayists[3] and cultural analysts[4] in reference to a movement made palatable to a general audience by celebrity supporters like Taylor Swift.[5] Mainstream feminism is often derisively referred to as "white feminism,"[6] a term implying that mainstream feminists don't fight for intersectionality with race, class, and sexuality. -

2254 Last December, While the National Organization for Women

SAUDI COURTS — WOMEN’S RIGHTS — GENERAL COURT OF QATIF SENTENCES GANG-RAPE VICTIM TO PRISON AND LASH- INGS FOR VIOLATING “ILLEGAL MINGLING” LAW. Last December, while the National Organization for Women (NOW) celebrated the success of its campaign for “non-sexist car in- surance,”1 a young woman already brutalized by her neighbors awaited further violence from her state. The previous month, Saudi Arabia’s General Court of Qatif had sentenced her to six months in prison and two hundred lashes for riding in a car with an unrelated male acquaintance, after which she was gang-raped by seven men.2 Her subsequent pardon by King Abdullah3 indicates the power of in- ternational outrage and pressure, but the lack of energy with which Western women’s rights groups participated in that outrage and pres- sure is indicative of a larger and troubling trend. Feminist groups too often do not help women abroad, but they can help, and they should help, because the need for their support is far greater overseas than at home.4 Although the reasons for their choice to prioritize sometimes relatively trivial matters in America over life-threatening issues facing women across the ocean may not be known, its effect is all too appar- ent: less pressure on foreign governments to end the suffering of mil- lions of subjugated Islamic women. With a legal system based on a strict interpretation of Islam,5 Saudi Arabia is a state of gender apartheid. For women permitted to work — they comprise 5.4% of the workforce6 — office buildings are segre- gated.7 For women taught to read — the illiteracy rate for women is ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 1 Nat’l Org. -

Her-042 Summer 2008 V21n5.Qxp

WOMEN’S CYCLES (MOTORCYCLES, THAT IS) | TACKLING WIFE ABUSE IN AFGHANISTAN | SUMMER READING GUIDE & MORE! WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS Summer 2008 Vol. 22 No. 1 Made in Canada JANE RULES THE BELOVED AUTHOR SHARES HER THOUGHTS ON LIVING, LOVING AND WRITING SIZING UP FASHION JANE RULE 1931–2007 ZERO TOLERANCE FOR SIZE ZERO $6.95 Canada/US Publications TOSHI Mail Agreement No. 40008866; PAP Registration No. 07944 Return Undeliverable Addresses to: REAGON PO Box 128, Winnipeg, MB R3C 2G1 Canada FINDING THE GOOD Display until September 15, 2008 WhyIJoinedtheCAW AA Young Young Worker's Worker's Story Story Iusedto ButonceI think my got injured... job was the greatest... Nobody was Things changed when there I joined the CAW... to help... Nowthere'salwayssomeoneinmycorner. Wanna join? Visit: www.caw.ca or call 1-877-495-6551 Email: [email protected] SUMMER 2008 / VOLUME 22 NO. 1 news DOMESTIC ASSAULT IN AFGHANISTAN 6 by Lauryn Oates 8 CAMPAIGN UPDATES MY HEART BELONGS IN THE CAPE 12 by Anat Cohen ITALIAN WOMEN MOBILIZE 13 by Meagan Williams 6: Addressing Domestic Assault in Afghanistan WHAT IF EQUALITY RULED? 14 by Shari Graydon features HOW THE MEDIA KEEPS US HUNG UP 16 ON BODY IMAGE By Shari Graydon JANE RULES 20 It has been said that every child on Galiano learned to swim in Jane Rule and Helen Sonthoff ’s swimming pool. The couple bought their house on Galiano Island as a weekend getaway in the 1970s, fell in love with it and never left. Rule’s legacy is explored in this intimate interview completed in the year before her passing.