The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism by Cassie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THESIS KD Final

The London School of Economics and Political Science Representing SlutWalk London in Mass and Social Media: Negotiating Feminist and Postfeminist Sensibilities Keren Darmon A thesis submitted to the Department of Media and Communications of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, June 2017 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 57,074 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Ms. Jean Morris. 2 Epigraphs It has been a hostile climate for feminism: it didn’t thrive, but it didn’t die; it survives, it is nowhere and everywhere – and the phoenix is flying again. (Campbell, 2013, p. 4) As Prometheus stole fire from the gods, so feminists will have to steal the power of naming from men, hopefully to better effect. (Dworkin, 1981, p. 17) 3 Abstract When SlutWalk marched onto the protest scene, with its focus on ending victim blaming and slut shaming, it carried the promise of a renewed feminist politics. -

Nepali Women Nepali Women

her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/11/09 12:04 PM Page C1 PINK PANTY THE WOMEN’S FALL OF PROTEST MOVEMENT PATRIARCHY INDIA PUB ATTACK IS THERE ROOM ANGERS WOMEN FOR MEN? IMMINENT WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS Fall 2009 Vol. 23 No. 2 Made in Canada AFGHANAFGHAN WOMENWOMEN STAND STRONG AGAINST SHIA LALAWW NEPALINEPALI WOMENWOMEN FIGHTFIGHT FORFOR CONSTITUTIONALCONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTSRIGHTS $6.75 Canada/US Publications Mail Agreement No. 40008866; PAP Registration No. 07944 Return Undeliverable Addresses to: PO Box 128, Winnipeg, MB R3C 2G1 Canada Display until December 15, 2009 her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/10/09 1:03 PM Page C2 Joss Maclennan Design, CEP Local 591-G Joss Maclennan Design, CEP Local 591-G CAWCAW womenwomen WeWe marchmarch forfor equality. equality. WeWe speakspeak outout for for justice. justice. We fight for change. We fight for change. For more information on women’s Forissues more and information rights please on visit women’s issueswww.caw.ca/women and rights please visit www.caw.ca/women CAW Full Sum-09.indd 1 28/05/09 5:19 PM her-047 Fall 2009 v23n2.qxp 9/11/09 12:05 PM Page 1 FALL 2009 / VOLUME 23 NO. 2 news THE MOTHER OF ALL MUSEUMS 6 by Janet Nicol TEL AVIV SHOOTING IGNITES GAY RIGHTS 7 by Idit Cohen TIANANMEN MOTHERS REFUSE TO FORGET 22: Yvette Nolan 8 by Janet Nicol NEPALI WOMEN DEMAND EQUALITY 9 by Chelsea Jones 12 CAMPAIGN UPDATES PARENTING BILL WOULD ERODE RIGHTS 13 by Pamela Cross features IS FEMINISM MEN’S WORK, TOO? 16 It’s not called the women’s movement for nothing. -

MIAMI UNIVERSITY the Graduate School

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Bridget Christine Gelms Candidate for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ______________________________________ Dr. Jason Palmeri, Director ______________________________________ Dr. Tim Lockridge, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Michele Simmons, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Lisa Weems, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT VOLATILE VISIBILITY: THE EFFECTS OF ONLINE HARASSMENT ON FEMINIST CIRCULATION AND PUBLIC DISCOURSE by Bridget C. Gelms As our digital environments—in their inhabitants, communities, and cultures—have evolved, harassment, unfortunately, has become the status quo on the internet (Duggan, 2014 & 2017; Jane, 2014b). Harassment is an issue that disproportionately affects women, particularly women of color (Citron, 2014; Mantilla, 2015), LGBTQIA+ women (Herring et al., 2002; Warzel, 2016), and women who engage in social justice, civil rights, and feminist discourses (Cole, 2015; Davies, 2015; Jane, 2014a). Whitney Phillips (2015) notes that it’s politically significant to pay attention to issues of online harassment because this kind of invective calls “attention to dominant cultural mores” (p. 7). Keeping our finger on the pulse of such attitudes is imperative to understand who is excluded from digital publics and how these exclusions perpetuate racism and sexism to “preserve the internet as a space free of politics and thus free of challenge to white masculine heterosexual hegemony” (Higgin, 2013, n.p.). While rhetoric and writing as a field has a long history of examining myriad exclusionary practices that occur in public discourses, we still have much work to do in understanding how online harassment, particularly that which is gendered, manifests in digital publics and to what rhetorical effect. -

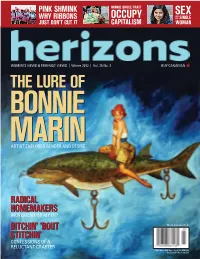

Samhita Mukhopadhyay and Jaclyn Friedman Take the Theory to the Next Level

PINK SHMINK MINNIE BRUCE PRATT SEX AND WHY RIBBONS OCCUPY THE SINGLE JUST DON’T CUT IT CAPITALISM WOMAN WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS | Winter 2012 | Vol. 25 No. 3 BUY CANADIAN THETHE LURELURE OFOF BONNIEBONNIE MARINMARIN ARTIST EXPLORES GENDER AND DESIRE RADICAL HOMEMAKERS MOVEMENT OR MYTH? BITCHIN’ ’BOUT $6.75 Canada/U.S. STITCHIN’ CONFESSIONS OF A RELUCTANT CRAFTER Publications Mail Agreement No. 40008866; Display until March 30, 2012 CAW Full (bleed) Win-12.indd 1 11-11-28 2:03 PM WINTER 2012 / VOLUME 25 NO. 3 news SEEING RED OVER PINK . 6 by Amanda Le Rougetel CAMPAIGN UPDATES . 8 THE POET VS. THE PROFITEERS AN INTERVIEW WITH MINNIE BRUCE PRATT . 11 by Joy Parks 11 features CONFESSIONS OF A RELUCTANT CRAFTER . .14 The knitting trend has hit Canada by storm. So what’s a feminist to do: Join the rebel fibre movement or cast dire warnings that women will soon be barefoot in the kitchen? by Deborah Ostrovsky BASTARDS AND BULLIES . .20 Dorothy Palmer’s debut novel, When Fenelon Falls, features Jordan, a young girl who is adopted and disabled. The protagonist reflects some of Palmer’s experiences about what it is like to be adopted and disabled. by Niranjana Iyer THE LURE OF BONNIE MARIN: LESSONS IN TRANSGRESSIONS . .24 Visual artist Bonnie Marin freely mixes gender, race and even species in erotic environments that are part middle class 1950s normalcy and part spectacles of perversity. 14 by Shawna Dempsey HOW FEMINISM CAN IMPROVE YOUR SEX LIFE . .28 Two new books about sex and politics paint a provocative picture of feminist dating 45 years after the personal was declared to be political. -

Narrating the Nation of Palestine by Nuzhat Abbas

SPECIAL OFFER FOR CONFERENCE DELEGATES See inside for details • Canada $5.95/US $5.95 • Vol. 16 No.4 • Spring 2003 WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS NARRATINGNARRATING THETHE NATIONNATION OFOF PALESTINEPALESTINE AN INTERVIEW WITH NAHLA ABDO WHYWHY DODO LESBIANSLESBIANS BATTER?BATTER? JANICE RISTOCK WANTS TO KNOW THETHE HEARTHEART DOESDOES NOTNOT BENDBEND A CONVERSATION WITH MAKEDA SILVERA NAC NAC. Who’s There? Lisa B. Rundle: Marshalling in the Third Wave Pump up the Volume: Veda Hille, Afua Cooper, Jorane Made in Canada in Made table of contents SPRING 2003 / VOLUME 16 NO. 4 FEATURES NARRATING THE NATION 18 OF PALESTINE Arab feminist Nahla Abdo has written extensively about women and military confrontation and is the founder of a gender research unit within a mental health program in Gaza. A sociology professor at Carleton University, Ms Abdo talks to Herizons about the PLO, Israel, Palestinian women and about her upcoming book, Sexuality, Citizenship and the Nation State: Experiences of Palestinian Women. by Nuzhat Abbas IN CONVERSATION WITH 23 MAKEDA SILVERA Toronto author Makeda Silvera discusses mother- hood, poverty, colonialism and the creative process with author Elizabeth Ruth. “I’ve always questioned the imperial culture’s view of motherhood: mothers are virtuous, mothers are asexual…” by Elizabeth Ruth WHY DO LESBIANS Page 26: Janice Ristock 26 BATTER? A decade ago, Janice Ristock and some colleagues produced a booklet on violence in lesbian relation- NEWS ships. Now the Winnipeg researcher has written a groundbreaking book on the issue. VILLAGERS JOIN CAMPAIGN by Helen Fallding 6 AGAINST FGM A Senegalese women’s organization called Tostan, which means ‘breakthrough’ in the Wolof language, ARTS & LIT sponsors education programs that have influenced the decision of 708 villages to make public declara- CAN LIT tions to abandon the generations-old practice of 32 FICTION female genital mutilation. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. A CRITICAL ACCOUNT OF IDEOLOGY IN CONSUMER CULTURE: The Commodification of a Social Movement Alexandra Serra Rome Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh University of Edinburgh Business School 2016 DECLARATION I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own and has been composed by myself. To the best of my knowledge, it does not contain material previously written or published by another person unless clearly indicated. The work herein presented has not been submitted for the purposes of any other degree or professional qualification. Date: 2 May 2016 Alexandra Serra Rome ___________________________________ I II To Frances, Florence, Betty, and Angela The strong-willed women in my life who have shaped me to be the person I am today. This thesis is dedicated to you. -

A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page Lyndsey S

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 2015 A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page Lyndsey S . Collins Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Collins, Lyndsey S ., "A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 2559. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd/2559 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr by Lyndsey S. Collins A Thesis Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sociology Lehigh University May 18, 2015 © 2015 Copyright (Lyndsey S. Collins) ii Thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Sociology. A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page Lyndsey Collins ____________________ Date Approved Dr. Jacqueline Krasas Dr. Yuping Zhang Dr. Nicola Tannenbaum iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis advisor, Dr. Jacqueline Krasas, who has provided me with invaluable insights, support, and encouragement throughout the entirety of this process. In addition, I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Nicola Tannenbaum -

Presentations Introduction Recent Feminist De

Beyond the Generational Line: An Exploration of Feminist Online Sites and Self-(Re)presentations Yi-lin Yu National Ilan University, Taiwan Abstract This article deals with the feminist generation issue by tracing the transition from generational to non-generational thinking in recent feminist discourse on third-wave feminism. Informed by certain feminist recommendations of affording alternative paradigms in place of the oceanic wave metaphor to describe the rela- tionships between different feminists, this study offers the insights gained from an investigation with three feminist online sites, The F Word, Eminism, and Guerrilla Girls, in which these online feminists have participated in building up a third wave consciousness or a third space site through their engagement in (re)presenting their feminist selves and identities. In developing a both/and third wave con- sciousness, these online feminists have bypassed the dualistic understanding of sec- ond and third wave feminism and reached a cross-generational commonality of adhering to feminist ideology and coalition in cyberspace as a third space. Through a content analysis of their online feminist self-(re)presentations, this pa- per concludes by arguing that they have not only reformulated the concept of third wave feminism but also worked toward a new configuration of third space narratives and subjectivities that sheds light on contemporary feminist thinking about feminist genealogy and history. Key words third-wave feminism, feminist generation, feminist online sites, self-(re)presentation Introduction Recent feminist development of third-wave discourses has been bom- barded with a conundrum regarding generational debates. Although 54 ❙ Yi-lin Yu some feminist scholars are preoccupied with using familial metaphors to depict different feminist generations, others have called forth a rethink- ing of the topic in non-generational terms. -

Everyday Feminism in the Digital Era: Gender, the Fourth Wave, and Social Media Affordances

EVERYDAY FEMINISM IN THE DIGITAL ERA: GENDER, THE FOURTH WAVE, AND SOCIAL MEDIA AFFORDANCES A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Urszula M. Pruchniewska May 2019 Examining Committee Members: Carolyn Kitch, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Media and Communication Adrienne Shaw, Media and Communication Rebecca Alpert, Religion ABSTRACT The last decade has seen a pronounced increase in feminist activism and sentiment in the public sphere, which scholars, activists, and journalists have dubbed the “fourth wave” of feminism. A key feature of the fourth wave is the use of digital technologies and the internet for feminist activism and discussion. This dissertation aims to broadly understand what is “new” about fourth wave feminism and specifically to understand how social media intersect with everyday feminist practices in the digital era. This project is made up of three case studies –Bumble the “feminist” dating app, private Facebook groups for women professionals, and the #MeToo movement on Twitter— and uses an affordance theory lens, examining the possibilities for (and constraints of) use embedded in the materiality of each digital platform. Through in-depth interviews and focus groups with users, alongside a structural discourse analysis of each platform, the findings show how social media are used strategically as tools for feminist purposes during mundane online activities such as dating and connecting with colleagues. Overall, this research highlights the feminist potential of everyday social media use, while considering the limits of digital technologies for everyday feminism. This work also reasserts the continued need for feminist activism in the fourth wave, by showing that the material realities of gender inequality persist, often obscured by an illusion of empowerment. -

Her-042 Summer 2008 V21n5.Qxp

WOMEN’S CYCLES (MOTORCYCLES, THAT IS) | TACKLING WIFE ABUSE IN AFGHANISTAN | SUMMER READING GUIDE & MORE! WOMEN’S NEWS & FEMINIST VIEWS Summer 2008 Vol. 22 No. 1 Made in Canada JANE RULES THE BELOVED AUTHOR SHARES HER THOUGHTS ON LIVING, LOVING AND WRITING SIZING UP FASHION JANE RULE 1931–2007 ZERO TOLERANCE FOR SIZE ZERO $6.95 Canada/US Publications TOSHI Mail Agreement No. 40008866; PAP Registration No. 07944 Return Undeliverable Addresses to: REAGON PO Box 128, Winnipeg, MB R3C 2G1 Canada FINDING THE GOOD Display until September 15, 2008 WhyIJoinedtheCAW AA Young Young Worker's Worker's Story Story Iusedto ButonceI think my got injured... job was the greatest... Nobody was Things changed when there I joined the CAW... to help... Nowthere'salwayssomeoneinmycorner. Wanna join? Visit: www.caw.ca or call 1-877-495-6551 Email: [email protected] SUMMER 2008 / VOLUME 22 NO. 1 news DOMESTIC ASSAULT IN AFGHANISTAN 6 by Lauryn Oates 8 CAMPAIGN UPDATES MY HEART BELONGS IN THE CAPE 12 by Anat Cohen ITALIAN WOMEN MOBILIZE 13 by Meagan Williams 6: Addressing Domestic Assault in Afghanistan WHAT IF EQUALITY RULED? 14 by Shari Graydon features HOW THE MEDIA KEEPS US HUNG UP 16 ON BODY IMAGE By Shari Graydon JANE RULES 20 It has been said that every child on Galiano learned to swim in Jane Rule and Helen Sonthoff ’s swimming pool. The couple bought their house on Galiano Island as a weekend getaway in the 1970s, fell in love with it and never left. Rule’s legacy is explored in this intimate interview completed in the year before her passing. -

Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository

Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page Collins, Lyndsey S . 2015 Find more at https://preserve.lib.lehigh.edu/ This document is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr by Lyndsey S. Collins A Thesis Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sociology Lehigh University May 18, 2015 © 2015 Copyright (Lyndsey S. Collins) ii Thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Sociology. A Content Analysis of the Women Against Feminism Tumblr Page Lyndsey Collins ____________________ Date Approved Dr. Jacqueline Krasas Dr. Yuping Zhang Dr. Nicola Tannenbaum iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis advisor, Dr. Jacqueline Krasas, who has provided me with invaluable insights, support, and encouragement throughout the entirety of this process. In addition, I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Nicola Tannenbaum and Dr. Yuping Zhang, for investing their time and energy into this project to make it a success. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………….……………………………………………….….…iv List of Tables……………………………………………………………………….vi List of Figures……………………………………………………………….……..vii Abstract…………..…………………………………………………………………..1 -

An Intersectional Analysis of Sexual Violence Policies, Responses, and Prevention Efforts at Ontario Universities

An intersectional analysis of sexual violence policies, responses, and prevention efforts at Ontario universities Emily M. Colpitts A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate program in Gender, Feminist and Women’s Studies York University Toronto, Ontario August 2019 © Emily Colpitts, 2019 Abstract In the context of public scrutiny, heightened media attention, and the introduction of provincial legislation on campus sexual violence, Canadian post-secondary institutions are facing unprecedented pressure to respond. This dissertation critically analyzes how sexual violence is being conceptualized in post-secondary institutions’ policies, responses, and prevention efforts. Specifically, the dissertation engages with the qualitative findings emerging from discourse analysis of post-secondary institutions’ sexual violence policies and interviews with 31 stakeholders, including students, faculty, and staff involved in efforts to prevent and address sexual violence at three Ontario universities and members of community anti-violence organizations. The project is grounded in an intersectional analysis of sexual violence, which de- centres the ‘ideal’ survivor and challenges the dominant depoliticized framing of sexual violence as an interpersonal issue by revealing its structural dimensions and its intersections with systems of oppression. While a number of Ontario universities reference intersectionality in their sexual violence policies,