Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Stafford

A Newsletter For Poets & Poetry Volume 11, Issue 3 - December 2006 Photo/Kit Stafford Board of Trustees Chair: Shelley Reece The Portland Tim Barnes Portland 2007 Elizabeth Barton Vancouver Patricia Carver Lake Oswego WILLIAM Don Colburn Portland STAFFORD Martha Gatchell Drain Sulima Malzin King City BIRTHDAY Paulann Petersen Portland EVENTS Dennis Schmidling Lake Oswego Helen Schmidling Lake Oswego � Joseph Soldati Portland Readings and Ann Staley Corvallis Celebrations Rich Wandschneider Enterprise Around the Nancy Winklesky Oregon City Photo/Estate of William Stafford Country Patty Wixon Ashland After side-stepping a lynch-mob for being a pacifist during World War II, William Stafford takes up his guitar for reconciliation. Sharon Wood Wortman Portland National Advisors: Join Us As We Celebrate the Spirit of William Stafford Marvin Bell Robert Bly Each year, the Friends of William Stafford rolls out members of the audience are invited to read their own Kurt Brown the red carpet to celebrate the late poet’s birthday favorite Stafford poem or share a memory. If you are Lucille Clifton (January 17, 1914) with a full month of Birthday new to the poetry of William Stafford, you may just James DePreist Celebration Readings. These events are held in enjoy hearing it for the first time. You can also learn Donald Hall communities throughout the country, and each more about us and sign up for a free newsletter. We Maxine Kumin year more are added. Free and open to the public, look forward to sharing this time with you and welcome Li-Young Lee they offer old friends and new a chance to share in your feedback at www. -

Yiddish and the Avant-Garde in American Jewish Poetry Sarah

Yiddish and the Avant-Garde in American Jewish Poetry Sarah Ponichtera Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 ©2012 Sarah Ponichtera All rights reserved All Louis Zukofsky material Copyright Paul Zukofsky; the material may not be reproduced, quoted, or used in any manner whatsoever without the explicit and specific permission of the copyright holder. A fee will be charged. ABSTRACT Yiddish and the Avant-Garde in American Jewish Poetry Sarah Ponichtera This dissertation traces the evolution of a formalist literary strategy through the twentieth century in both Yiddish and English, through literary and historical analyses of poets and poetic groups from the turn of the century until the 1980s. It begins by exploring the ways in which the Yiddish poet Yehoash built on the contemporary interest in the primitive as he developed his aesthetics in the 1900s, then turns to the modernist poetic group In zikh (the Introspectivists) and their efforts to explore primitive states of consciousness in individual subjectivity. In the third chapter, the project turns to Louis Zukofsky's inclusion of Yehoash's Yiddish translations of Japanese poetry in his own English epic, written in dialogue with Ezra Pound. It concludes with an examination of the Language poets of the 1970s, particularly Charles Bernstein's experimental verse, which explores the way that language shapes consciousness through the use of critical and linguistic discourse. Each of these poets or poetic groups uses experimental poetry as a lens through which to peer at the intersections of language and consciousness, and each explicitly identifies Yiddish (whether as symbol or reality) as an essential component of their poetic technique. -

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Commemoration

Der Partizaner-himen––Hymn of the Partisans Annual Gathering Commemorating Words by Hirsh Glik; Music by Dmitri Pokras Wa rsaw Ghetto Uprising Zog nit keyn mol az du geyst dem letstn veg, The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising khotsh himlen blayene farshteln bloye teg. Commemoration Kumen vet nokh undzer oysgebenkte sho – s'vet a poyk ton undzer trot: mir zaynen do! TODAY marks the 75th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Each April 19th, survivors, the Yiddish cultural Fun grinem palmenland biz vaysn land fun shney, community, Bundists, and children of resistance fighters and mir kumen on mit undzer payn, mit undzer vey, Holocaust survivors gather in Riverside Park at 83rd Street at 75th Anniversary un vu gefaln s'iz a shprits fun undzer blut, the plaque dedicated to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in order to shprotsn vet dort undzer gvure, undzer mut! mark this epic anniversary and to pay tribute to those who S'vet di morgnzun bagildn undz dem haynt, fought and those who perished in history’s most heinous crime. un der nekhtn vet farshvindn mit dem faynt, On April 19, 1943, the first seder night of Passover, as the nor oyb farzamen vet di zun in dem kayor – Nazis began their liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto, a group of vi a parol zol geyn dos lid fun dor tsu dor. about 220 out of 50,000 remaining Jews staged a historic and Dos lid geshribn iz mit blut, un nit mit blay, heroic uprising, holding the Nazis at bay for almost a full month, s'iz nit keyn lidl fun a foygl oyf der fray. -

End the Occupation! Jewish Feminists in the U.S

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Resist Newsletters Resist Collection 3-31-1990 Resist Newsletter, Mar. 1990 Resist Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter Recommended Citation Resist, "Resist Newsletter, Mar. 1990" (1990). Resist Newsletters. 222. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter/222 Newsletter #224 A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority March, 1990 End the Occupation! Jewish Feminists in the U.S. Working for Peace in the Middle East TATIANA SCHREIBER There's a Jewish expression, "You are not expected to complete the work in your lifetime. Neither must you refuse to do your part." For a long time I have wanted to do my part in speaking out against the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Yet, as one murder of a Palestinian teenager at the beginning of the Intifada became one murder every day, as homes were demolished, as Palestinian schools were arbitrarily closed, as Palestinians were summarily expelled from Jerusalem, I remained very quiet. I don't know exactly why I have found it so difficult to know what my work should be, but I suspect it is Demonstrators link arms around the old city of Jerusalem in 1990 Time for Peace Actions. Photo: Eleanor Roffman largely due to some buried fear that in speaking out I could be cast out from to speak out? How did their friends - the Israeli/Palestinian conflict. my home, such as it is, in the Jewish Jewish and non-Jewish - react? Were What follows is a sampling from the community. But, in the last few years, their families supportive or critical? many conversations I had with Jewish as editor of the Resist newsletter, and as Had they grown up in a Zionist tradi women determined not to "give up, a member of the Resist board, I've had tion? Did their feelings about the work shut up, or put up" with the Israeli gov the opportunity to learn about the kind change as the Intifada continued into ernment's version of reality. -

Reader's Guide

a reader’s guide to The World to Come by Dara Horn Made possible by The Deschutes Public Library Foundation, Inc. and The Starview Foundation, ©2008 1 A Novel Idea: Celebrating Five Years 2 Author Dara Horn 3 That Picture. That Cover. 5 Discussion Questions 7 The Russian Pogroms & Jewish Immigration to America 9 Marc Chagall 12 Der Nister 15 Yiddish Fiction Overview 19 Related Material 26 Event Schedule A Novel Idea celebrating five years A Novel Idea ... Read Together celebrates five years of success and is revered as the leading community read program in Oregon. Much of our success is due to the thousands of Deschutes County residents who embrace the program and participate actively in its free cultural events and author visits every year. Through A Novel Idea, we’ve trekked across the rivers and streams of Oregon with David James Duncan’s classic The River Why, journeyed to the barren and heart-breaking lands of Afghanistan through Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner, trucked our way through America and Mexico with María Amparo Escandón’s González and Daughter Trucking Co., and relived the great days of Bill Bowerman’s Oregon with Kenny Moore’s book Bowerman and the Men of Oregon. This year, we enter The World to Come with award-winning author Dara Horn and are enchanted by this extraordinary tale of mystery, folklore, theology, and history. A month-long series of events kicks off on Saturday, April 1 26 with the Obsidian Opera performing songs from Fiddler on the Roof. More than 20 programs highlight this year’s book at the public libraries in Deschutes County including: Russian Jewish immigrant experience in Oregon, the artist Marc Chagall, Jewish baking, Judaism 101, art workshops, a Synagogue tour, and book discussions—all inspired from the book’s rich tale. -

Gender and the Body in Yiddish Literature // Jewish Studies 39L

Gender and the Body in Yiddish Literature // Jewish Studies 39L Instructor: Anna Elena Torres ~ [email protected] W 2-4 p.m., 201 Giannini, Fall 2015 Office hours: Melo Melo cafe (1701 University Ave at McGee), Thursday noon-2pm This course will explore the representation of the body and gender in Yiddish literature, particularly engaging with questions of race, disability, and religiosity. Literature will span both religious and secular texts, from medieval memoir to 20th Century experimental poetry. Using gender theory as a lens into the world of Yiddish writing, we will encounter medieval troubadours and healers, spirit possession, avant-garde performance. Familiarity with Yiddish is not required. All literature will be in English translation. Any students of Yiddish are also invited to read the texts in the original. Required Texts Course reader, available at Instant Copying and Laser Printing (ask for Arnon) Celia Dropkin, The Acrobat, transl. by Faith Jones, Jennifer Kronovet, and Samuel Solomon, 2014 God of Vengeance, Sholem Asch. Translated by Donald Margulies. Glikl. The Memoirs of Gluckel of Hameln. Translation by Lowenthal (1977 edition) Students should also consult the YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, a tremendous online resource: http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/default.aspx - 1 - Course Objectives: This course is an introduction to Yiddish literature and theories of gender, disability, and embodiment. The readings combine primary and secondary source materials, chosen to offer a taste of the breadth of styles and genres within Yiddish literature. Students are required to complete all readings prior to class and be prepared to discuss them in a respectful manner with their fellow students. -

Feminist Periodicals

The Un vers ty of W scons n System Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents WOMEN'S STUDIES Volume 22, Number 3, Fall 2002 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard LIBRARIAN Women's Studies Librarian Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents Volume 22, Number 3 Fall 2002 Periodical literature is the culling edge of women's scholarship, feminist theory, and much of women's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is published by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing pUblic awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to a journal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table of contents pages from current issues of major feminist journals are reproduced in each issue of Feminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As pUblication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. 2. Frequency of publication. 3. U.S. subscription price(s). -

The Issue Is Power

2nd Edition The Issue Is Power Essays on Women, Jews, Violence and Resistance Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz Foreword by Julie R. Enszer aunt lute books SAN FRANCISCO Copyright © 1992 by Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz “What Makes Revolution?” copyright © 2018 by Julie R. Enszer All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Aunt Lute Books Print ISBN: 9781951874001 P.O. Box 410687 ebook ISBN: 9781939904362 San Francisco, CA 94141 First Edition Second Edition Cover Art: Melissa Levin Senior Editor: Joan Pinkvoss Cover and Text Design: Pamela Wilson Artistic Director: Shay Brawn Design Studio Managing Editor: A.S. Ikeda Typesetting: Joan Meyers Cover Design: A.S. Ikeda Production: Jayna Brown, Patti Casey, Typesetting: A.S. Ikeda Martha Davis, Chris Lymbertos, Cathy Production: Maya Sisneros, María Nestor, Renée Stephens, Kathleen Mínguez-Arias, Cindy Ho, Emma Wilkinson Rosenbaum Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kaye/Kantrowitz, Melanie, author. Title: The issue is power : essays on women, jews, violence and resistance / Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz ; foreword by Julie R. Enszer. Description: 2nd Edition. | San Francisco : Aunt Lute Books, 2020. | Revised edition of the author’s The issue is power, c1992. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2019056837 (print) | LCCN 2019056838 (ebook) | ISBN 9781951874001 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9781939904362 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Jewish women--United States. | Feminism--United States. | Lesbianism--United States. | Antisemitism--United States. | Power (Social sciences) | Jewish-Arab relations. Classification: LCC HQ1172 .K39 2020 (print) | LCC HQ1172 (ebook) | DDC 305.48/8924073--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019056837 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019056838 Printed in the U.S.A. -

Gulf Islands

Great Kids! Tennis SEE INSIDE Open tourney. SEE PAGE A28 Arts Review Michael Hames. SEE PAGE A17 GULF ISLANDS $ 2525 Wednesday, September 5, 2007 — YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1960 47TH YEAR – ISSUE 36 1(incl.(in(i( nclccl.l GST)GSGST)T) TENNIS INVESTIGATION KPMG report confirms PARC tennis misplays Recommends ways “There was a knowledge gap between what you need to avoid future to know to build a structure of this nature and what the fumbles commission knew,” said BY GAIL SJUBERG KPMG associate partner DRIFTWOOD EDITOR Gordon Gunn at a Thursday At least 20 factors con- public meeting at the Port- tributed to a failed indoor lock Park portable. tennis project that took a Regional director Gary Hol- big bite out of Salt Spring’s man, who also sits on PARC parks and recreation bud- and recommended approv- get and delivered nothing, al of a $572,150 contract to says a consultants’ report Cover-All Pacifi c to the Capi- released August 30. tal Regional District (CRD) A poorly written request Board in September 2005, for proposals, lack of con- said the point of the $20,000 sultation with experts or CRD-commissioned report investigation into the land’s was not to lay blame but to zoning restrictions were just ensure the same type of mis- a few items on the long list of takes don’t happen again. defi ciencies KPMG Advisory “The intent of the review PHOTO BY DERRICK LUNDY Services found in the Parks is to try to understand where FAREWELL TO SHELBY POOL: Alex Barnes’ eighth birthday party was one of the last celebrations to ever be held in and Recreation Commission there were flaws before in (PARC) attempt to build a the decision-making process Shelby Pool on Saturday, as the facility has been given to the Pender Island swim club. -

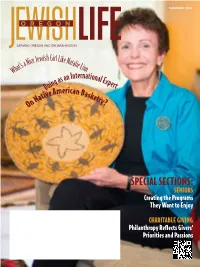

SPECIAL SECTIONS: SENIORS Creating the Programs They Want to Enjoy

NOVEMBER 2014 SERVING OREGON AND SW WASHINGTON e Jewish Girl Like N a Nic atalie hat’s Linn W ern s an Int ational ng a Expe Doi rt American B tive aske Na try On ? SPECIAL SECTIONS: SENIORS Creating the Programs They Want to Enjoy CHARITABLE GIVING Philanthropy Reflects Givers’ Priorities and Passions Jewish Federation of Greater Portland invites you to THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 13 beginning at 5:30 pm Mittleman Jewish Community Center $36 before November 7, $45 after purchase tickets today at Three Surgeons, One Goal ThreeNow open Surgeons, in the Pearl One District Goal www.jewishportland.org/impact HelpingNow open patients in achieve the Pearlbeautiful District results Helping patients achieve beautiful results andHelping improved patients self-confidence. achieve beautiful 30 resultsyears or call Rachel at 503-892-7413 and improved self-confidence. 30 years ofand combined improved experience self-confidence. in a full 30suite years of combined experience in a full suite of services:combined experience in a full suite •of Cosmetic services: & reconstructive breast surgery •*of Cosmetic services: & reconstructive breast surgery • CosmeticCosmetic & & reconstructive reconstructive breast breast surgery surgery •* Cosmetic & reconstructive breast surgery * BodyCosmetic contouring & reconstructive & liposuction breast surgery •* BodyBody contouring contouring & & liposuction liposuction •* Body contouring & liposuction •* FacialBody contouringcosmetic surgery & liposuction & non-surgical •* FacialBody contouringcosmetic surgery & liposuction -

“Progressive” Jewish Thought New Anti-Semitism

“Progressive” Jewish Thought and the New Anti-Semitism Alvin H. Rosenfeld AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE “Progressive” Jewish Thought and the New Anti-Semitism Alvin H. Rosenfeld The American Jewish Committee protects the rights and freedoms of Jews the world over; combats bigotry and anti-Semitism and promotes human rights for all; works for the security of Israel and deepened under- standing between Americans and Israelis; advocates public policy positions rooted in American democratic values and the perspectives of the Jewish heritage; and enhances the creative vitality of the Jewish people. Founded in 1906, it is the pioneer human-relations agency in the United States. To learn more about our mission, programs, and publications, and to join and contribute to our efforts, please visit us at www.ajc.org or contact us by phone at 212-751-4000 or by e-mail at [email protected]. AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE Contents Alvin H. Rosenfeld is professor of English and Jewish Foreword v Studies and director of the Institute for Jewish Culture and the Arts, Indiana University. His most recent pub- “Progressive” Jewish Thought lication for the American Jewish Committee is Anti- and the New Anti-Semitism 1 Zionism in Great Britain and Beyond: A “Respectable” Anti-Semitism?, published in 2004. Manifestations of Anti-Semitism in the Muslim World 1 A Conflation of Interests: Manifestations of Anti-Semitism in Europe 4 What Is New in Today’s Anti-Semitism? 7 Questioning Israel’s Essence, Not Israeli Policies 8 A Jew among the Anti-Zionists: Jacqueline Rose 9 Copyright © 2006 American Jewish Committee All Rights Reserved December 2006 iii iv Contents Michael Neumann and the Accusation of Genocide with all Jews Complicit 13 Foreword Jewish Opposition to Zionism How can there be something “new” about something as old as anti- in Historical Perspective 14 Semitism? Hostility to Jews—because of their religious beliefs, their social or ethnic distinctiveness, or their imputed “racial” differ- ences—has been around for a long time. -

Marc Blattner Changing the Face of Jewish Portland

SEPTEMBER 2012 SERVING OREGON AND SW WASHINGTON Marc Blattner Changing the face of Jewish Portland Special Sections High Holy Days Coming soon to a shul near you Arts & Entertainment Jewish performers take center stage Home Improvement Optimism returns for residential projects WISHES YOU A SWEET AND HAPPY NEW YEAR! Together WE do extraordinary things. ® THE STRENGTH OF A PEOPLE. Stay connected to your community with our e-newsletter. THE POWER OF COMMUNITY. Contact us at 503.245.6219 | www.jewishportland.org JewishPDX EXPERIENCE AND SERVICE MAKE THE DIFFERENCE CONFIDENTIALITY • PROFESSIONALISM • INTEGRITY • DEDICATION • TECHNOLOGY ITALIAN PALLADIAN VILLA - PORTLAND HEIGHTS DISTINCTIVE WEST HILLS ESTATE NEW PRICE ML#12388457 ML#12466223 COUNCIL CREST COLONIAL HELVETIA COUNTRY ESTATE PORTLAND HEIGHTS CAPE COD WISHES YOU A NEW NEW SWEET AND HAPPY NEW YEAR! ML#12505032 ML#12317566 ML#12336142 MJ STEEN Principal Broker Cronin & Caplan Realty Group, Inc. www.mjsteen.com 503-497-5199 For 30 years we’ve helped bring peace of mind to Creative over 20,000 clients during one of life’s toughest times. OREGON ◆ S.W. WASHINGTON 503.227.1515 360.823.0410 Together WE do extraordinary things. GevurtzMenashe.com ® THE STRENGTH OF A PEOPLE. Stay connected to your community with our e-newsletter. THE POWER OF COMMUNITY. Contact us at 503.245.6219 | www.jewishportland.org Divorce ■ Children ■ Support JewishPDX ISRAEL BONDS FOR THE NEW YEAR Invest in a Nation of Heritage, Courage and Inspiration 2012 ∙ 5773 High Holidays Purchase Israel Bonds Online israelbonds.com Development Corporation for Israel/Israel Bonds Western Region 1950 Sawtelle Blvd, Suite 295 · Los Angeles 90025 800.922.6637 · (fax) 310.996.3006 · [email protected] Follow Israel Bonds on Twitter and Facebook This is not an offering, which can be made only by prospectus.