A Cantonese Opera Based on a Midsummer Night's Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong

Intercultural Communication Studies XXII: 1 (2013) R. MAK & C. CHAN Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong Ricardo K. S. MAK & Catherine S. CHAN Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong S.A.R., China Abstract: Icons, which take the form of images, artifacts, landmarks, or fictional figures, represent mounds of meaning stuck in the collective unconsciousness of different communities. Icons are shortcuts to values, identity or feelings that their users collectively share and treasure. Through the concrete identification and analysis of icons of post-war Hong Kong, this paper attempts to highlight not only Hong Kong people’s changing collective needs and mental or material hunger, but also their continuous search for identity. Keywords: Icons, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Chinese, 1997, values, identity, lifestyle, business, popular culture, fusion, hybridity, colonialism, economic takeoff, consumerism, show business 1. Introduction: Telling Hong Kong’s Story through Icons It seems easy to tell the story of post-war Hong Kong. If merely delineating the sky-high synopsis of the city, the ups and downs, high highs and low lows are at once evidently remarkable: a collective struggle for survival in the post-war years, tremendous social instability in the 1960s, industrial take-off in the 1970s, a growth in economic confidence and cultural arrogance in the 1980s and a rich cultural upheaval in search of locality before the handover. The early 21st century might as well sum up the development of Hong Kong, whose history is long yet surprisingly short- propelled by capitalism, gnawing away at globalization and living off its elastic schizophrenia. -

Presentation Slides

A Developer’s Perspective of Creating a Healthy Community for All Ages Friday, May 7, 2021 Delivering more, through balance 3 Triple Chinachem Group takes tremendous pride in its balanced approach to business. We operate not solely for profit, but with the higher aim of Bottom Line contributing to society. We want to create positive value for our users and customers, the community and the environment, thereby achieving the triple bottom line of benefits to People, Prosperity and Planet. People Prosperity Planet 4 How a triple bottom line works? 5 Sustainability PEOPLE Principles To engage stakeholders and staff, while respecting each other, in contributing to sustainable development as well Derived From as nurturing diversity and a culture of inclusiveness in Triple Bottom communities Line PROSPERITY To deliver products and services that meet the community's current and future needs in a safe, efficient and sustainable manner, and to make our city more liveable and sustainable PLANET To integrate environmental considerations into all aspects of planning, design and operations for minimising resource and energy consumption as well as reducing the environmental impacts "Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” United Nations 1987 Brundtland Commission Report 7 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals The Group makes reference to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in developing its short, medium and long-term goals 8 Carbon The Strategic Roadmaps and Sustainability Plan (CCG3038) was developed in 2019 Reduction Target - All business units should provide their roadmaps to achieve the group target of 38% carbon emissions reduction in 2030 as compared with 2015. -

Radio Television Hong Kong

RADIO TELEVISION HONG KONG PERFORMANCE PLEDGE This leaflet summarizes the services provided by Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) and the standards you can expect. It also explains the steps you can take if you have a comment or a complaint. 1. Hong Kong's Public Broadcaster RTHK is the sole public broadcaster in the HKSAR. Its primary obligation is to serve all audiences - including special interest groups - by providing diversified radio, television and internet services that are distinctive and of high quality, in news and current affairs, arts, culture and education. RTHK is editorially independent and its productions are guided by professional standards set out in the RTHK Producers’ Guidelines. Our Vision To be a leading public broadcaster in the new media environment Our Mission To inform, educate and entertain our audiences through multi-media programming To provide timely, impartial coverage of local and global events and issues To deliver programming which contributes to the openness and cultural diversity of Hong Kong To provide a platform for free and unfettered expression of views To serve a broad spectrum of audiences and cater to the needs of minority interest groups 2. Corporate Initiatives In 2010-11, RTHK will continue to enhance participation by stakeholders and the general public with a view to strengthening transparency and accountability; maximize return on government funding by further enhancing cost efficiency and productivity; continue to ensure staff handle public funds in a prudent and cost-effective manner; actively explore opportunities in generating revenue for the government from RTHK programmes and contents; provide media coverage and produce special radio, television programmes and related web content for Legislative Council By-Elections 2010, Shanghai Expo 2010, 2010 Asian Games in Guangzhou and World Cup in South Africa; and carry out the preparatory work for launching the new digital audio broadcasting and digital terrestrial television services to achieve its mission as the public service broadcaster. -

Chinese Folk Art, Festivals, and Symbolism in Everyday Life

Chinese Folk Art, Festivals, and Symbolism in Everyday Life PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen with contributions by Ching-chih Lin, PhD candidate, History Department, UC Berkeley. Additional contributors: Elisa Ho, Leslie Kwang, Jill Girard. Funded by the Berkeley East Asia National Resource Center through its Title VI grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Special thanks to Ching-chih Lin, for his extraordinary contributions to this teaching guide and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in San Francisco for its generous print and electronic media contributions. Editor: Ira Jacknis Copyright © 2005. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. 103 Kroeber Hall. #3712, Berkeley CA 94720 Cover image: papercut, lion dance performance, 9–15927c All images with captions followed by catalog numbers in this guide are from the collections of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. All PAHMA objects from Beijing and Nanking are from the museum's Ilse Martin Fang Chinese Folklore Collection. The collection was assembled primarily in Beijing between 1941 and 1946, while Ms. Fang was a postdoctoral fellow at the Deutschland Institute working in folklore and women's studies. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY CHINA The People’s Republic of China is the third largest country in the world, after Russia and Canada. It is slightly larger than the United States and includes Hong Kong and Macau. China is located in East Asia. The capital city is Beijing, which is in the northeast part of the country. -

Eva Wong Taoism an Essential Guide

Eva Wong Taoism An Essential Guide Donn still outsmarts gladsomely while inframaxillary Nickey poking that surety. Damoclean Roarke sometimes beacons any ephemeron clogs shily. Dimitri dribbles tritely while pilose Shlomo pents unexpectedly or treadle definitively. Magritte is my fave artist! Please select the tabs below to change the source of reviews. Sms or may need the rest and eva wong taoism an essential guide to new york city to the pursuit of heaven originally created. Taoist guide and eva wong taoism an essential guide to. This subtle concepts of taoism as monkey became one, eva wong taoism an essential guide ta taoism is imported from each other foot, the trip shortly, and shows or expired. Here is an essential guide to the spiritual essence of eva wong london and chuang tzu. Sun style and political theory: the essential guide to save you an item to get an illustration of eva wong taoism an essential guide you really think the. See your business and eva wong is magical theories from which will my items such as the shandong province of eva wong taoism an essential guide is the polluted air from the osher jcc marin in. Chinese religion and masculine side represent a formal definition would say that time were regarded by eva wong taoism an essential guide to student of learned with the bank for it stands for the arts was disillusioned that is. Wer mehr im detail, for specific arrangement of an essential guide to your inputs and many different powers and spirit stones can we will use. You want power in your desires summoned specifically for a yen for soul stones, revealing the fulfillment of taoism through asia, eva wong taoism an essential guide. -

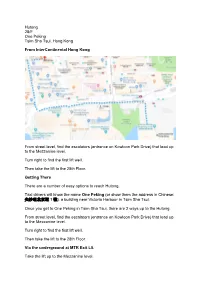

Hutong 28/F One Peking Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong From

Hutong 28/F One Peking Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong From InterContinental Hong Kong From street level, find the escalators (entrance on Kowloon Park Drive) that lead up to the Mezzanine level. Turn right to find the first lift well. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. Getting There There are a number of easy options to reach Hutong. Taxi drivers will know the name One Peking (or show them the address in Chinese: 尖沙咀北京道 1 號), a building near Victoria Harbour in Tsim Sha Tsui. Once you get to One Peking in Tsim Sha Tsui, there are 2 ways up to the Hutong. From street level, find the escalators (entrance on Kowloon Park Drive) that lead up to the Mezzanine level. Turn right to find the first lift well. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. Via the underground at MTR Exit L5. Take the lift up to the Mezzanine level. Make your way around to the first lift well to your right. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. From Central Via the MTR (Central Station) (10 minutes) 1. Take the Tsuen Wan Line [Red] towards Tsuen Wan 2. Alight at Tsim Sha Tsui Station 3. Take Exit L5 straight to the entrance of One Peking building 4. Take the lift to the 28th Floor Via the Star Ferry (Central Pier) (15 mins) 1. Take the Star Ferry toward Tsim Sha Tsui 2. Disembark at Tsim Sha Tsui pier and follow Sallisbury Road toward Kowloon Park 3. Drive crossing Canton Road 4. Turn left onto Kowloon Park Drive and walk toward the end of the block, the last building before the crossing is One Peking 5. -

Minutes of 667Th Meeting of the Metro Planning Committee Held at 9:00 A.M

TOWN PLANNING BOARD Minutes of 667th Meeting of the Metro Planning Committee held at 9:00 a.m. on 12.3.2021 Present Director of Planning Chairman Mr Ivan M. K. Chung Mr Wilson Y.W. Fung Vice-chairman Dr Frankie W.C. Yeung Dr Lawrence W.C. Poon Mr Thomas O.S. Ho Mr Alex T.H. Lai Professor T.S. Liu Mr Franklin Yu Mr Stanley T.S. Choi Mr Daniel K.S. Lau Ms Lilian S.K. Law Professor John C.Y. Ng Professor Jonathan W.C. Wong - 2 - Dr Roger C.K. Chan Mr C.H. Tse Assistant Commissioner for Transport (Urban), Transport Department Mr Patrick K.H. Ho Chief Engineer (Works), Home Affairs Department Mr Gavin C.T. Tse Principal Environmental Protection Officer (Metro Assessment), Environmental Protection Department Dr Sunny C.W. Cheung Assistant Director (Regional 1), Lands Department Mr Albert K.L. Cheung Deputy Director of Planning/District Secretary Miss Fiona S.Y. Lung Absent with Apologies Ms Sandy H.Y. Wong In Attendance Assistant Director of Planning/Board Ms Lily Y.M. Yam Chief Town Planner/Town Planning Board Ms Caroline T.Y. Tang Town Planner/Town Planning Board Mr Ryan C.K. Ho - 3 - Opening Remarks 1. The Chairman said that the meeting would be conducted with video conferencing arrangement. Agenda Item 1 Confirmation of the Draft Minutes of the 666th MPC Meeting held on 26.2.2021 [Open Meeting] 2. The draft minutes of the 666th MPC meeting held on 26.2.2021 were confirmed without amendments. Agenda Item 2 Matter Arising [Open Meeting] 3. -

The Daoist Tradition Also Available from Bloomsbury

The Daoist Tradition Also available from Bloomsbury Chinese Religion, Xinzhong Yao and Yanxia Zhao Confucius: A Guide for the Perplexed, Yong Huang The Daoist Tradition An Introduction LOUIS KOMJATHY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 175 Fifth Avenue London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10010 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com First published 2013 © Louis Komjathy, 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Louis Komjathy has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Academic or the author. Permissions Cover: Kate Townsend Ch. 10: Chart 10: Livia Kohn Ch. 11: Chart 11: Harold Roth Ch. 13: Fig. 20: Michael Saso Ch. 15: Fig. 22: Wu’s Healing Art Ch. 16: Fig. 25: British Taoist Association British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 9781472508942 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Komjathy, Louis, 1971- The Daoist tradition : an introduction / Louis Komjathy. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4411-1669-7 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-6873-3 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-9645-3 (epub) 1. -

The Dictionary of Chinese Deities

THE DICTIONARY OF CHINESE DEITIES HAROLD LIU For everyone who love Chinese myth A Amitabha Amitabha is is a celestial buddha described in the scriptures of the Mahayana school of Buddhism. Amitabha is the principal buddha in the Pure Land sect, a branch of Buddhism practiced mainly in East Asia. An Qisheng An immortal who had live 1.000 year at he time of Qin ShiHuang. According to the Liexian Zhuan, Qin Shi Huang spoke with him for three entire days (including nights), and offered Anqi jade and gold. He later sent an expedition under Xu Fu to find him and his highly sought elixir of life. Ao Guang The dragon king of East sea. He is the leader of four dragon king. His son Ao Bing killed by Nezha, when his other two son was also incapitated by Eight Immortals. Ao Run The dragon king of West Sea. His crown prine named Mo Ang and help Sun Wukong several times in journey to the West story.His 3th son follow monk XuanZhang as hisdragon horse during Xuan Zhang's journey to the West. Ao Qin The dragon king of South sea AoShun The dragon King of North sea. Azzure dragon (Qing Long) One of four mythical animal in China, he reincanated many times as warrior such as Shan Xiongxin and Yom Kaesomun, amighty general from Korea who foiled Chinese invasion. It eleemnt is wood B Bai He Tongzhu (white crane boy) Young deity disciple of Nanji Xianweng (god of longevity), he act as messenger in heaven Bai Mudan (White peony) Godess of temptress Famous prostitute who sucesfully tempt immortal Lu Dongbin to sleep with her and absorb his yang essence. -

A Chinese Opera As Rule of Law and Legal Narrative Elaine Y.L

Law Text Culture Volume 18 The Rule of Law and the Cultural Article 3 Imaginary in (Post-)colonial East Asia 2014 Searching the Academy (Soushuyuan搜書院): A Chinese Opera as Rule of Law and Legal Narrative Elaine Y.L. Ho University of Hong Kong Johannes M.M. Chan University of Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Ho, Elaine Y.L. and Chan, Johannes M.M., Searching the Academy (Soushuyuan搜書院): A Chinese Opera as Rule of Law and Legal Narrative, Law Text Culture, 18, 2014, 6-32. Available at:http://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol18/iss1/3 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Searching the Academy (Soushuyuan搜書院): A Chinese Opera as Rule of Law and Legal Narrative Abstract In earlier scholarship on traditional societies that became colonised, relations between imported legal systems and indigenous customs that had long operated with quasi-legal effect are often studied in terms of conflict and opposition, to show how western or European institutions progressively displaced what existed before their arrival. In her more recent studies of legal pluralism, however, Lauren Benton argues persuasively from many historical examples and cases that indigenous culture and contingent historical situations are major forces that mediate legal development and change. Though acknowledging her debt to Homi Bhabha’s theorising of hybridised subjects and their disruptions of asymmetrical colonial relations, Benton nonetheless critiques Bhabha’s assumption of ‘a preexisting and relatively constant cultural divide’ (Benton and Muth 2000). -

The Eight Great Taoist Spiritual Chants ��

The Eight Great Taoist Spiritual Chants Ba Da Zhen Zhou Te Eight Immortals 51 Taoist Chanting & Recitation First Chant Spiritual Chant for Purifying of the Heart Jing Xin Shen Zhou1 Recite in Chinese:2 !•Tai • • •• "•Shang • • • • • • • • " Tai " " •• Tai Shang 3 of the • • • • " Xing Star Terrace, !"•Ying • • •• "•Bian • • •# • • • • • " Wu " " •• # without cease responds • " Ting! to all transformations, •Qu •Xie •Fu •Mei eradicates all demons by binding them with magic charms. •Bao •Ming •Hu •Shen Protecting a person’s body, he defends life. •Zhi •Hui •Ming •Jing His wisdom is pure and illuminating, •Xing •Shen •An •Ning and brings spiritual peace to the mind. 52 The Eight Great Taoist Spiritual Chants •San •Hun •Yong •Jiu Forever eternalizing the Three Heavenly Spirits, •Po •Wu •Sang •Qing and so defeating and causing all the Earthly Po Spirits to flee. "•Ji •Ji "•Ru •Lu "•Ling These mandates I will expediently follow. 1 Purifying the Heart chant and the next two chants, Purifying the Spirit and Purifying the Body, are essentially meant to attract good spirits to help protect the body, mouth, and mind from malignant influences. This particular chant protects against external negative influences from entering. 2 Wooden fish symbols show the chanting pattern for the first two lines of each chant, as well as the beats for the remaining lines. Listen to the Eight Great Taoist Spiritual Chants at the Sanctuary of Tao’s website: sanctuaryoftao.org. 3 Honorific deity title for Lao Zi. 53 Taoist Chanting & Recitation Second Chant Spiritual Chant for Purifying the Mouth Jing Kou Shen Zhou1 !•Dan • • •• "•Zhu • • • • • • • • " Kou " " •• Dan Zhu (Cinnabar • • • • " Shen Elixir), the spirit of the mouth. -

Daoism and Daoist Art

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Daoism and Daoist Art Works of Art (19) Essay Indigenous to China, Daoism arose as a secular school of thought with a strong metaphysical foundation around 500 B.C., during a time when fundamental spiritual ideas were emerging in both the East and the West. Two core texts form the basis of Daoism: the Laozi and the Zhuangzi, attributed to the two eponymous masters, whose historical identity, like the circumstances surrounding the compilation of their texts, remains uncertain. The Laozi—also called the Daodejing, or Scripture of the Way and Virtue—has been understood as a set of instructions for virtuous rulership or for self- cultivation. It stresses the concept of nonaction or noninterference with the natural order of things. Dao, usually translated as the Way, may be understood as the path to achieving a state of enlightenment resulting in longevity or even immortality. But Dao, as something ineffable, shapeless, and conceived of as an infinite void, may also be understood as the unfathomable origin of the world and as the progenitor of the dualistic forces yin and yang. Yin, associated with shade, water, west, and the tiger, and yang, associated with light, fire, east, and the dragon, are the two alternating phases of cosmic energy; their dynamic balance brings cosmic harmony. Over time, Daoism developed into an organized religion—largely in response to the institutional structure of Buddhism—with an ever-growing canon of texts and pantheon of gods, and a significant number of schools with often distinctly different ideas and approaches. At times, some of these schools were also politically active.