Translating Religion in the Dream of the Red Chamber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INVERSE TRANSLATION in CHINA: a NECESSARY CHOICE OR a NECESSARY EVIL By

ARTICLES INVERSE TRANSLATION IN CHINA: A NECESSARY CHOICE OR A NECESSARY EVIL By JIASHENG SHI Associate Professor and Director of Translation Department, School of Translation and Interpreting, Jinan University, Zhuhai, China. ABSTRACT Inverse translation has long been seen in the negative light in modern translation studies, and has thus been relegated to a sort of second class endeavour. Based on a brief comparative study of English translations of Wenxin Diaolong1, a Chinese literary classic, this paper argues that inverse translation is as legitimate and feasible as direct translation in China, and that the assessment of quality of translation should be based more on the translator's translation competence and translation strategy than on his or her language affiliation. Keywords: Inverse Translation, Direct Translation, Wenxin Diaolong. INTRODUCTION for translation practice that is conducted from a foreign Inverse translation is “a term used to describe a translation, language into one's mother tongue—if they take into either written or spoken, which is done from the translator's account translation practice at all. This biased stance native language, or language of habitual use” concerning inverse translation is not conducive to the (Shuttleworth & Cowie 1997: 90). It is the opposite of direct development of translation studies, and runs contrary to translation, which refers to the translation done into the translation reality, where translation from one's mother translator's native language, or language of habitual use tongue into a foreign language is possible, permissible and (Shuttleworth & Cowie 1997: 41). Inverse translation is also some times even desirable. named “service translation” (Newmark 1988: 52). -

Modalities of Doing Religion and Ritual Polytropy: Evaluating the Religious

This article was downloaded by: [University of Cambridge] On: 12 February 2012, At: 13:02 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Religion Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rrel20 Modalities of doing religion and ritual polytropy: evaluating the religious market model from the perspective of Chinese religious history Adam Yuet Chau a a Department of East Asian Studies, Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Cambridge, Sidgwick Avenue, Cambridge, CB3 9DA, United Kingdom Available online: 22 Dec 2011 To cite this article: Adam Yuet Chau (2011): Modalities of doing religion and ritual polytropy: evaluating the religious market model from the perspective of Chinese religious history, Religion, 41:4, 547-568 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2011.624691 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture

In &a r*tm Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture edited by Sucheng Chan Exclusion and the Chinese Communify in America, r88z-ry43 Edited by Sucheng Chan Also in the series: Gary Y. Okihiro, Cane Fires: The Anti-lapanese Moaement Temple University press in Hawaii, t855-ry45 Philadelphia Chapter 6 The Kuomintang in Chinese American Kuomintang in Chinese American Communities 477 E Communities before World War II the party in the Chinese American communities as they reflected events and changes in the party's ideology in China. The Chinese during the Exclusion Era The Chinese became victims of American racism after they arrived in Him Lai Mark California in large numbers during the mid nineteenth century. Even while their labor was exploited for developing the resources of the West, they were targets of discriminatory legislation, physical attacks, and mob violence. Assigned the role of scapegoats, they were blamed for society's multitude of social and economic ills. A populist anti-Chinese movement ultimately pressured the U.S. Congress to pass the first Chinese exclusion act in 1882. Racial discrimination, however, was not limited to incoming immi- grants. The established Chinese community itself came under attack as The Chinese settled in California in the mid nineteenth white America showed by words and deeds that it considered the Chinese century and quickly became an important component in the pariahs. Attacked by demagogues and opportunistic politicians at will, state's economy. However, they also encountered anti- Chinese were victimizedby criminal elements as well. They were even- Chinese sentiments, which culminated in the enactment of tually squeezed out of practically all but the most menial occupations in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. -

Utopia/Wutuobang As a Travelling Marker of Time*

The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/./), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. doi:./SX UTOPIA/WUTUOBANG AS A TRAVELLING MARKER OF TIME* LORENZO ANDOLFATTO Heidelberg University ABSTRACT. This article argues for the understanding of ‘utopia’ as a cultural marker whose appearance in history is functional to the a posteriori chronologization (or typification) of historical time. I develop this argument via a comparative analysis of utopia between China and Europe. Utopia is a marker of modernity: the coinage of the word wutuobang (‘utopia’) in Chinese around is analogous and complementary to More’s invention of Utopia in ,inthatbothrepresent attempts at the conceptualizations of displaced imaginaries, encounters with radical forms of otherness – the European ‘discovery’ of the ‘New World’ during the Renaissance on the one hand, and early modern China’sown‘Westphalian’ refashioning on the other. In fact, a steady stream of utopian con- jecturing seems to mark the latter: from the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom borne out of the Opium wars, via the utopian tendencies of late Qing fiction in the works of literati such as Li Ruzhen, Biheguan Zhuren, Lu Shi’e, Wu Jianren, Xiaoran Yusheng, and Xu Zhiyan, to the reformer Kang Youwei’s monumental treatise Datong shu. -

Analysi of Dream of the Red Chamber

MULTIPLE AUTHORS DETECTION: A QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF DREAM OF THE RED CHAMBER XIANFENG HU, YANG WANG, AND QIANG WU A bs t r a c t . Inspired by the authorship controversy of Dream of the Red Chamber and the applica- tion of machine learning in the study of literary stylometry, we develop a rigorous new method for the mathematical analysis of authorship by testing for a so-called chrono-divide in writing styles. Our method incorporates some of the latest advances in the study of authorship attribution, par- ticularly techniques from support vector machines. By introducing the notion of relative frequency as a feature ranking metric our method proves to be highly e↵ective and robust. Applying our method to the Cheng-Gao version of Dream of the Red Chamber has led to con- vincing if not irrefutable evidence that the first 80 chapters and the last 40 chapters of the book were written by two di↵erent authors. Furthermore, our analysis has unexpectedly provided strong support to the hypothesis that Chapter 67 was not the work of Cao Xueqin either. We have also tested our method to the other three Great Classical Novels in Chinese. As expected no chrono-divides have been found. This provides further evidence of the robustness of our method. 1. In t r o du c t ion Dream of the Red Chamber (˘¢â) by Cao Xueqin (˘»é) is one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels. For more than one and a half centuries it has been widely acknowledged as the greatest literary masterpiece ever written in the history of Chinese literature. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Raiding the Garden and Rejecting the Family

Raiding the Garden and Rejecting the Family A Narratology of Scene in The Dream of the Red Chamber Zhonghong Chen Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Autumn 2014 II Raiding the Garden and Rejecting the Family: A Narratology of Scene in the Dream of Red Chamber A Master Thesis III © Zhonghong Chen 2014 Raiding the Garden and Rejecting the Family: A Narratology of Scene in the Dream of Red Chamber Zhonghong Chen http://www.duo.uio.no/ Printed by Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Summary By conducting a close reading and a structural analysis, this thesis explores a narratology of “scene” in the novel Dream of the Red Chamber(Honglou meng《红楼梦》). The terminology of “scene” in the Western literary criticism usually refers to “a structual unit in drama” and “a mode of presentation in narrative”. Some literature criticists also claim that “scene” refers to “a structural unit in narrative”, though without further explanation. One of the main contributions of this theis is to define the term of “scene”, apply it stringently to the novel, Honglou meng, and thus make a narratology of “scene” in this novel. This thesis finds that “scene” as a structural unit in drama is characterized by a unity of continuity of characters, time, space and actions that are unified based on the same topic. “Topic” plays a decisive role in distinguishing “scenes”. On the basis of the definition of the term of “scene”, this theis also reveals how “scenes” transfer from each other by analyzing “scene transitions”. This thesis also finds that the characteristic of the narration in Honglou meng is “character-centered” ranther than “plot-centered”, by conducting research on the relationship between “scene”, “chapter” and “chapter title”. -

Beijing, a Garden of Violence

Inter-Asia Cultural Studies ISSN: 1464-9373 (Print) 1469-8447 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/riac20 Beijing, a garden of violence Geremie R. Barmé To cite this article: Geremie R. Barmé (2008) Beijing, a garden of violence, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 9:4, 612-639, DOI: 10.1080/14649370802386552 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14649370802386552 Published online: 15 Nov 2008. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 153 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=riac20 Download by: [Australian National University] Date: 08 April 2016, At: 20:00 Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, Volume 9, Number 4, 2008 Beijing, a garden of violence Geremie R. BARMÉ TaylorRIAC_A_338822.sgm10.1080/14649370802386552Inter-Asia1464-9373Original200894000000DecemberGeremieBarmé[email protected] and& Article Francis Cultural (print)/1469-8447Francis 2008 Studies (online) ABSTRACT This paper examines the history of Beijing in relation to gardens—imperial, princely, public and private—and the impetus of the ‘gardener’, in particular in the twentieth-century. Engag- ing with the theme of ‘violence in the garden’ as articulated by such scholars as Zygmunt Bauman and Martin Jay, I reflect on Beijing as a ‘garden of violence’, both before the rise of the socialist state in 1949, and during the years leading up to the 2008 Olympics. KEYWORDS: gardens, violence, party culture, Chinese history, Chinese politics, cultivation, revolution The gardening impulse This paper offers a brief examination of the history of Beijing in relation to gardens— imperial, princely, socialist, public and private—and the impetus of the ‘gardener’, in particular during the twentieth century. -

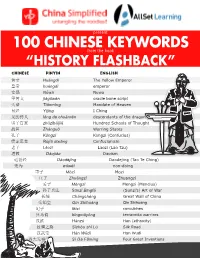

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

Notes Made in China in May 1990 for the BBC Radio Documentary *The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy* Gregory B

Notes made in China in May 1990 for the BBC radio documentary *The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy* Gregory B. Lee To cite this version: Gregory B. Lee. Notes made in China in May 1990 for the BBC radio documentary *The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy*. 2019. hal-02196338 HAL Id: hal-02196338 https://hal-univ-lyon3.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02196338 Preprint submitted on 28 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Gregory B. Lee. URGENT KNOCKING, China/Hong Kong Notebook, May 1990. Notes made in China in May 1990 in connection with the hour-long radio documentary The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy which I was making for the BBC and which was broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on 4the June 1990 to coincide with the 1st anniversary of the massacre at Tiananmen. My Urgent Knocking notebook is somewhat cryptic. I was worried about prying eyes, and the notes were not made in chronological, or consecutive order, but scattered throughout my notebook. Probably, I was hoping that their haphazard pagination would withstand a cursory inspection. -

Chapter Summaries 44–51, No Summaries Written by Wallace 52 (Winter)

page 1 Story of the Stone Highlights & Chapter Comments, chpts 1-43 created for SAA Fall 2009, John R Wallace Overview The 80 chapters of The Story of the Stone that we will read has about 30 major characters and several hundred minor characters. This level of detail can be difficult for the first-time (or even second-, third-time) reader to sort out. One reason for this, beyond the obvious information deluge, is the similar emphasis placed on both minor and major characters and events. Another reason is that characters are referred to by more than one name, and the names themselves are similar. (Some of the sameness in names is wordplay, to bond certain characters together.) These notes are meant to help identify characters and events close to the main narrative lines. In my opinion the three strongest storylines in this novel are: The changes that the tempestuous but empathetic Jia Bao-yu undergoes over the course of his life, beginning at about age 12. The romantic triangle of Jia Bao-yu and two women: the tearful, brilliant Lin Dai-yu and the charming, proper Xue Bao-chai. Wang Xi-feng’s charismatic personality, capable management skills, corruption and fate. All of these events occur in the context of a powerful house of declining fortunes, Confucian values that are definitely frayed around the edges, and a Buddhist (-Daoist) perspective that problematizes what should be taken as the Real. There is definitely reading pleasure in keeping these three stories in mind. However, just enjoying the small sub-stories, the many detailed descriptions, the wordplay, and so on, is without a doubt a major pleasure in reading this story. -

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: a Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: A Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in East Asian Studies April 2014 ©2014 Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Acknowledgements First of all, I thank Professor Ellen Widmer not only for her guidance and encouragement throughout this thesis process, but also for her support throughout my time here at Wellesley. Without her endless patience this study would have not been possible and I am forever grateful to be one of her advisees. I would also like to thank the Wellesley College East Asian Studies Department for giving me the opportunity to take on such a project and for challenging me to expand my horizons each and every day Sincerest thanks to my sisters away from home, Amy, Irene, Cristina, and Beatriz, for the many late night snacks, funny notes, and general reassurance during hard times. I would also like to thank Joe for never losing faith in my abilities and helping me stay motivated. Finally, many thanks to my family and friends back home. Your continued support through all of my endeavors and your ability to endure the seemingly endless thesis rambles has been invaluable to this experience. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1: THE PAIRING OF WOOD AND GOLD Lin Daiyu .................................................................................................