Raiding the Garden and Rejecting the Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adaptive Fuzzy Pid Controller's Application in Constant Pressure Water Supply System

2010 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (ICISE 2010) Hangzhou, China 4-6 December 2010 Pages 1-774 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1076H-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-7616-9 1 / 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS ADAPTIVE FUZZY PID CONTROLLER'S APPLICATION IN CONSTANT PRESSURE WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM..............................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Xiao Zhi-Huai, Cao Yu ZengBing APPLICATION OF OPC INTERFACE TECHNOLOGY IN SHEARER REMOTE MONITORING SYSTEM ...............................5 Ke Niu, Zhongbin Wang, Jun Liu, Wenchuan Zhu PASSIVITY-BASED CONTROL STRATEGIES OF DOUBLY FED INDUCTION WIND POWER GENERATOR SYSTEMS.................................................................................................................................................................................9 Qian Ping, Xu Bing EXECUTIVE CONTROL OF MULTI-CHANNEL OPERATION IN SEISMIC DATA PROCESSING SYSTEM..........................14 Li Tao, Hu Guangmin, Zhao Taiyin, Li Lei URBAN VEGETATION COVERAGE INFORMATION EXTRACTION BASED ON IMPROVED LINEAR SPECTRAL MIXTURE MODE.....................................................................................................................................................................18 GUO Zhi-qiang, PENG Dao-li, WU Jian, GUO Zhi-qiang ECOLOGICAL RISKS ASSESSMENTS OF HEAVY METAL CONTAMINATIONS IN THE YANCHENG RED-CROWN CRANE NATIONAL NATURE RESERVE BY SUPPORT -

I. the Excellencies and Above Chancellor of State 相國 and Assisting Chancellor 丞相

THE HUNDRED OFFICES OF WEI AND JIN A Brief Summary of the Bureaucracy of Wei and Jin Times Yang Zhengyuan This grew largely from a collection of personal notes used in trying to achieve some degree of consistency in the translation of office titles in various other translation projects. Hundred Offices (baiguan) 百官 is a term for bureaucracy. Though a thorough study of the government of the Han dynasty already exists in the form of The bureaucracy of Han times by Hans Bielenstein, the book is limited in scope to the early and middle Han dynasty. Bielenstein himself calculates the date of the Treatise on Bureaucracy of the Hou Han shu (HHS), a major source for his book, to between September 141 and September 142, meaning that it provides no information on the evolution of the bureaucracy through the collapse of Han or through the Three States period (220 – 280) to Jin. This work is not meant to be a replacement for Bielenstein’s work, but a supplement. Therefore emphasis is placed on differences and changes from the Han bureaucracy, and some familiarity with Bielenstein’s work and the basic structure of the Han bureaucracy is assumed. As San Guo zhi (SGZ) itself does not contain Treatises or Tables, the main sources are the Treatises on Bureaucracy in the Song shu (SS) of Shen Yue and Jin shu (JS) of Fang Xuanling et al. The translation of bureaucracy titles derives mainly from the continually evolving Dubs-Bielenstein-de Crespigny system, with some additional modifications. The main departure from the Dubs-Bielenstein- de Crespigny system is the effort to group together offices by level to aid the casual reader in guessing relative rank. -

Recent Articles from the China Journal of System Engineering Prepared

Recent Articles from the China Journal of System Engineering Prepared by the University of Washington Quantum System Engineering (QSE) Group.1 Bibliography [1] Mu A-Hua, Zhou Shao-Lei, and Yu Xiao-Li. Research on fast self-adaptive genetic algorithm and its simulation. Journal of System Simulation, 16(1):122 – 5, 2004. [2] Guan Ai-Jie, Yu Da-Tai, Wang Yun-Ji, An Yue-Sheng, and Lan Rong-Qin. Simulation of recon-sat reconing process and evaluation of reconing effect. Journal of System Simulation, 16(10):2261 – 3, 2004. [3] Hao Ai-Min, Pang Guo-Feng, and Ji Yu-Chun. Study and implementation for fidelity of air roaming system above the virtual mount qomolangma. Journal of System Simulation, 12(4):356 – 9, 2000. [4] Sui Ai-Na, Wu Wei, and Zhao Qin-Ping. The analysis of the theory and technology on virtual assembly and virtual prototype. Journal of System Simulation, 12(4):386 – 8, 2000. [5] Xu An, Fan Xiu-Min, Hong Xin, Cheng Jian, and Huang Wei-Dong. Research and development on interactive simulation system for astronauts walking in the outer space. Journal of System Simulation, 16(9):1953 – 6, Sept. 2004. [6] Zhang An and Zhang Yao-Zhong. Study on effectiveness top analysis of group air-to-ground aviation weapon system. Journal of System Simulation, 14(9):1225 – 8, Sept. 2002. [7] Zhang An, He Sheng-Qiang, and Lv Ming-Qiang. Modeling simulation of group air-to-ground attack-defense confrontation system. Journal of System Simulation, 16(6):1245 – 8, 2004. [8] Wu An-Bo, Wang Jian-Hua, Geng Ying-San, and Wang Xiao-Feng. -

Médecine Traditionnelle Chinoise Acupuncture & Pancréas

Médecine Traditionnelle Chinoise Acupuncture & Pancréas 1970-2007 Bibliographie Centre de documentation du GERA 192 chemin des cèdres Centre83130 de documentation La Garde France du GERA [email protected] chemin des cèdres 83130 La Garde France [email protected] référence type titre de l'article ou du document, (en langue originale ou traduction si entre crochets). numéro d'ordre relatif dans la bibliographie sélective. numéro de référence gera. Indiquer ce numéro pour toute demande de copie. disponibilité du document di: disponible, nd: non disponible, rd: résumé seul disponible, type de document. ra: revue d'acupuncture re: revue extérieure cg: congrès, co: cours tt: traité th: thèse me: mémoire, tp: tiré-à-part. el: extrait de livre 1 -gera:6785/di/ra ACUPUNCTURE ANAESTHESIA: A REVIEW. SMALL TJ. american journal of acupuncture.1974,2(3), 147-3. (eng). réf:33 titre de la revue ou éditeur. première et éventuellement nombre de références dernière page d'un bibliographiques du article, ou nombre document. de pages d'un traité, auteur, année de publication. thèse ou mémoire. premier auteur si suivi de et al. langue de publication et résumé: volume et/ou indique un résumé en anglais (pour les documents non en anglais) numéro. * (fra) français, (eng) anglais, (deu) allemand, (ita) italien, (esp) espagnol, (por) portugais, (ned) hollandais, (rus) russe, (pol) polonais, (cze) tchèque, (rou) roumain, (chi) chinois, (jap) japonais, (cor) coréen, (vie) vietnamien. Les résumés correspondent soit à la reproduction du résumé de l'auteur centre de documentation du gera ℡ 04.96.17.00.30 192 chemin des cèdres 04.96.17.00.31 83130 La Garde [email protected] France demande de copie de document Les reproductions sont destinées à des fins exclusives de recherches et réservées à l'usage du demandeur. -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

The Darkest Red Corner Matthew James Brazil

The Darkest Red Corner Chinese Communist Intelligence and Its Place in the Party, 1926-1945 Matthew James Brazil A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy Department of Government and International Relations Business School University of Sydney 17 December 2012 Statement of Originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted previously, either in its entirety or substantially, for a higher degree or qualifications at any other university or institute of higher learning. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Matthew James Brazil i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before and during this project I met a number of people who, directly or otherwise, encouraged my belief that Chinese Communist intelligence was not too difficult a subject for academic study. Michael Dutton and Scot Tanner provided invaluable direction at the very beginning. James Mulvenon requires special thanks for regular encouragement over the years and generosity with his time, guidance, and library. Richard Corsa, Monte Bullard, Tom Andrukonis, Robert W. Rice, Bill Weinstein, Roderick MacFarquhar, the late Frank Holober, Dave Small, Moray Taylor Smith, David Shambaugh, Steven Wadley, Roger Faligot, Jean Hung and the staff at the Universities Service Centre in Hong Kong, and the kind personnel at the KMT Archives in Taipei are the others who can be named. Three former US diplomats cannot, though their generosity helped my understanding of links between modern PRC intelligence operations and those before 1949. -

Chapter Summaries 44–51, No Summaries Written by Wallace 52 (Winter)

page 1 Story of the Stone Highlights & Chapter Comments, chpts 1-43 created for SAA Fall 2009, John R Wallace Overview The 80 chapters of The Story of the Stone that we will read has about 30 major characters and several hundred minor characters. This level of detail can be difficult for the first-time (or even second-, third-time) reader to sort out. One reason for this, beyond the obvious information deluge, is the similar emphasis placed on both minor and major characters and events. Another reason is that characters are referred to by more than one name, and the names themselves are similar. (Some of the sameness in names is wordplay, to bond certain characters together.) These notes are meant to help identify characters and events close to the main narrative lines. In my opinion the three strongest storylines in this novel are: The changes that the tempestuous but empathetic Jia Bao-yu undergoes over the course of his life, beginning at about age 12. The romantic triangle of Jia Bao-yu and two women: the tearful, brilliant Lin Dai-yu and the charming, proper Xue Bao-chai. Wang Xi-feng’s charismatic personality, capable management skills, corruption and fate. All of these events occur in the context of a powerful house of declining fortunes, Confucian values that are definitely frayed around the edges, and a Buddhist (-Daoist) perspective that problematizes what should be taken as the Real. There is definitely reading pleasure in keeping these three stories in mind. However, just enjoying the small sub-stories, the many detailed descriptions, the wordplay, and so on, is without a doubt a major pleasure in reading this story. -

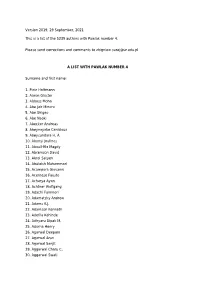

Version 2019, 14 May, 2021 This Is a List of the 5239 Authors With

Version 2019, 29 September, 2021 This is a list of the 5239 authors with Pawlak number 4. Please send corrections and comments to [email protected] A LIST WITH PAWLAK NUMBER 4 Surname and first name: 1. Piotr Hoffmann 2. Aaron Gloster 3. Abbass Mona 4. Abe Jair Minoro 5. Abe Shigeo 6. Abe Naoki 7. Abecker Andreas 8. Abeynayake Canicious 9. Abeysundara H. A. 10. Abonyi Jnullnos 11. Aboull-Ela Magdy 12. Abramson David 13. Abrol Satyen 14. Abulaish Muhammad 15. Acampora Giovanni 16. Acernese Fausto 17. Acharya Ayan 18. Achtner Wolfgang 19. Adachi Fuminori 20. Adamatzky Andrew 21. Adams K.J. 22. Adamson Kenneth 23. Adefila Kehinde 24. Adhyaru Dipak M. 25. Adorna Henry 26. Agarwal Deepam 27. Agarwal Arun 28. Agarwal Sanjit 29. Aggarwal Charu C. 30. Aggarwal Swati 31. Aguan Kripamoy 32. Agui Takeshi 33. Ahluwalia Madhu 34. Ahmad Tanvir 35. Ahmad Nesar 36. Ahmed Rafiq 37. Ahmed Rosina 38. Ahn Rennull M. C. 39. Ai Lingmei 40. Aidinis Vassilis 41. Airola Antti 42. Aizawa Akiko N. 43. Akbari Mohammad Ali 44. Akedo Naoya 45. Akhgar Babak 46. Akkermans Hans 47. Al-Bayatti Ali H. 48. Al-Dubaee Shawki A. 49. Al-Hmouz Ahmed 50. Al-Hmouz Rami 51. Al-Khateeb Tahseen 52. Al-Mayyan Waheeda 53. Al-Shenawy Nada M. 54. Al-Yami Maryam 55. Alam S. S. 56. Alam Mansoor 57. Alami Rachid 58. Albathan Mubarak 59. Alberg Dima 60. Alcalnull Rafael 61. Alcalnull-Fdez Jesnulls 62. Alcnullntara Otnullvio D. A. 63. Alfaro-Garc?a V?ctor 64. Alhazov Artiom 65. Alhimale Laila 66. -

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: a Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: A Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in East Asian Studies April 2014 ©2014 Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Acknowledgements First of all, I thank Professor Ellen Widmer not only for her guidance and encouragement throughout this thesis process, but also for her support throughout my time here at Wellesley. Without her endless patience this study would have not been possible and I am forever grateful to be one of her advisees. I would also like to thank the Wellesley College East Asian Studies Department for giving me the opportunity to take on such a project and for challenging me to expand my horizons each and every day Sincerest thanks to my sisters away from home, Amy, Irene, Cristina, and Beatriz, for the many late night snacks, funny notes, and general reassurance during hard times. I would also like to thank Joe for never losing faith in my abilities and helping me stay motivated. Finally, many thanks to my family and friends back home. Your continued support through all of my endeavors and your ability to endure the seemingly endless thesis rambles has been invaluable to this experience. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1: THE PAIRING OF WOOD AND GOLD Lin Daiyu ................................................................................................. -

DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Rewriting to Reproduce Beauty a Comparative Case Study of Hong Lou Meng Xu, Binglu

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Rewriting to reproduce beauty A comparative case study of Hong Lou Meng Xu, Binglu Award date: 2020 Awarding institution: Queen's University Belfast Link to publication Terms of use All those accessing thesis content in Queen’s University Belfast Research Portal are subject to the following terms and conditions of use • Copyright is subject to the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988, or as modified by any successor legislation • Copyright and moral rights for thesis content are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners • A copy of a thesis may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research/study without the need for permission or charge • Distribution or reproduction of thesis content in any format is not permitted without the permission of the copyright holder • When citing this work, full bibliographic details should be supplied, including the author, title, awarding institution and date of thesis Take down policy A thesis can be removed from the Research Portal if there has been a breach of copyright, or a similarly robust reason. If you believe this document breaches copyright, or there is sufficient cause to take down, please contact us, citing details. Email: [email protected] Supplementary materials Where possible, we endeavour to provide supplementary materials to theses. This may include video, audio and other types of files. We endeavour to capture all content and upload as part of the Pure record for each thesis. Note, it may not be possible in all instances to convert analogue formats to usable digital formats for some supplementary materials. We exercise best efforts on our behalf and, in such instances, encourage the individual to consult the physical thesis for further information. -

Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou Meng

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Honors Program in History (Senior Honors Theses) Department of History March 2007 Authorial Disputes: Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou meng Carina Wells [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors Wells, Carina, "Authorial Disputes: Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou meng" (2007). Honors Program in History (Senior Honors Theses). 6. https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/6 A Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History. Faculty Advisor: Siyen Fei This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/6 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authorial Disputes: Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou meng Comments A Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History. Faculty Advisor: Siyen Fei This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/6 University of Pennsylvania Authorial Disputes: Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou meng A senior thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in History by Carina L. Wells Philadelphia, PA March 23, 2003 Faculty Advisor: Siyen Fei Honors Director: Julia Rudolph Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………...i Explanatory Note…………………………………………………………………………iv Dynasties and Periods……………………………………………………………………..v Selected Reign -

UC GAIA Chen Schaberg CS5.5-Text.Indd

Idle Talk New PersPectives oN chiNese culture aNd society A series sponsored by the American Council of Learned Societies and made possible through a grant from the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange 1. Joan Judge and Hu Ying, eds., Beyond Exemplar Tales: Women’s Biography in Chinese History 2. David A. Palmer and Xun Liu, eds., Daoism in the Twentieth Century: Between Eternity and Modernity 3. Joshua A. Fogel, ed., The Role of Japan in Modern Chinese Art 4. Thomas S. Mullaney, James Leibold, Stéphane Gros, and Eric Vanden Bussche, eds., Critical Han Studies: The History, Representation, and Identity of China’s Majority 5. Jack W. Chen and David Schaberg, eds., Idle Talk: Gossip and Anecdote in Traditional China Idle Talk Gossip and Anecdote in Traditional China edited by Jack w. cheN aNd david schaberg Global, Area, and International Archive University of California Press berkeley los Angeles loNdoN The Global, Area, and International Archive (GAIA) is an initiative of the Institute of International Studies, University of California, Berkeley, in partnership with the University of California Press, the California Digital Library, and international research programs across the University of California system. University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd.