I. the Excellencies and Above Chancellor of State 相國 and Assisting Chancellor 丞相

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Authority in the Han Dynasty: Focus on the Sanlao

Local Authority in the Han Dynasty: Focus on the Sanlao Jiandong CHEN 㱩ڎ暒 School of International Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Technology Sydney Australia A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Technology Sydney Sydney, Australia 2018 Certificate of Original Authorship I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. This thesis is the result of a research candidature conducted with another University as part of a collaborative Doctoral degree. Production Note: Signature of Student: Signature removed prior to publication. Date: 30/10/2018 ii Acknowledgements The completion of the thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Associate Professor Jingqing Yang for his continuous support during my PhD study. Many thanks for providing me with the opportunity to study at the University of Technology Sydney. His patience, motivation and immense knowledge guided me throughout the time of my research. I cannot imagine having a better supervisor and mentor for my PhD study. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee: Associate Professor Chongyi Feng and Associate Professor Shirley Chan, for their insightful comments and encouragement; and also for their challenging questions which incited me to widen my research and view things from various perspectives. -

Médecine Traditionnelle Chinoise Acupuncture & Pancréas

Médecine Traditionnelle Chinoise Acupuncture & Pancréas 1970-2007 Bibliographie Centre de documentation du GERA 192 chemin des cèdres Centre83130 de documentation La Garde France du GERA [email protected] chemin des cèdres 83130 La Garde France [email protected] référence type titre de l'article ou du document, (en langue originale ou traduction si entre crochets). numéro d'ordre relatif dans la bibliographie sélective. numéro de référence gera. Indiquer ce numéro pour toute demande de copie. disponibilité du document di: disponible, nd: non disponible, rd: résumé seul disponible, type de document. ra: revue d'acupuncture re: revue extérieure cg: congrès, co: cours tt: traité th: thèse me: mémoire, tp: tiré-à-part. el: extrait de livre 1 -gera:6785/di/ra ACUPUNCTURE ANAESTHESIA: A REVIEW. SMALL TJ. american journal of acupuncture.1974,2(3), 147-3. (eng). réf:33 titre de la revue ou éditeur. première et éventuellement nombre de références dernière page d'un bibliographiques du article, ou nombre document. de pages d'un traité, auteur, année de publication. thèse ou mémoire. premier auteur si suivi de et al. langue de publication et résumé: volume et/ou indique un résumé en anglais (pour les documents non en anglais) numéro. * (fra) français, (eng) anglais, (deu) allemand, (ita) italien, (esp) espagnol, (por) portugais, (ned) hollandais, (rus) russe, (pol) polonais, (cze) tchèque, (rou) roumain, (chi) chinois, (jap) japonais, (cor) coréen, (vie) vietnamien. Les résumés correspondent soit à la reproduction du résumé de l'auteur centre de documentation du gera ℡ 04.96.17.00.30 192 chemin des cèdres 04.96.17.00.31 83130 La Garde [email protected] France demande de copie de document Les reproductions sont destinées à des fins exclusives de recherches et réservées à l'usage du demandeur. -

Raiding the Garden and Rejecting the Family

Raiding the Garden and Rejecting the Family A Narratology of Scene in The Dream of the Red Chamber Zhonghong Chen Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Autumn 2014 II Raiding the Garden and Rejecting the Family: A Narratology of Scene in the Dream of Red Chamber A Master Thesis III © Zhonghong Chen 2014 Raiding the Garden and Rejecting the Family: A Narratology of Scene in the Dream of Red Chamber Zhonghong Chen http://www.duo.uio.no/ Printed by Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Summary By conducting a close reading and a structural analysis, this thesis explores a narratology of “scene” in the novel Dream of the Red Chamber(Honglou meng《红楼梦》). The terminology of “scene” in the Western literary criticism usually refers to “a structual unit in drama” and “a mode of presentation in narrative”. Some literature criticists also claim that “scene” refers to “a structural unit in narrative”, though without further explanation. One of the main contributions of this theis is to define the term of “scene”, apply it stringently to the novel, Honglou meng, and thus make a narratology of “scene” in this novel. This thesis finds that “scene” as a structural unit in drama is characterized by a unity of continuity of characters, time, space and actions that are unified based on the same topic. “Topic” plays a decisive role in distinguishing “scenes”. On the basis of the definition of the term of “scene”, this theis also reveals how “scenes” transfer from each other by analyzing “scene transitions”. This thesis also finds that the characteristic of the narration in Honglou meng is “character-centered” ranther than “plot-centered”, by conducting research on the relationship between “scene”, “chapter” and “chapter title”. -

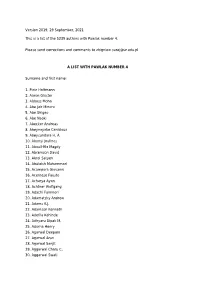

Version 2019, 14 May, 2021 This Is a List of the 5239 Authors With

Version 2019, 29 September, 2021 This is a list of the 5239 authors with Pawlak number 4. Please send corrections and comments to [email protected] A LIST WITH PAWLAK NUMBER 4 Surname and first name: 1. Piotr Hoffmann 2. Aaron Gloster 3. Abbass Mona 4. Abe Jair Minoro 5. Abe Shigeo 6. Abe Naoki 7. Abecker Andreas 8. Abeynayake Canicious 9. Abeysundara H. A. 10. Abonyi Jnullnos 11. Aboull-Ela Magdy 12. Abramson David 13. Abrol Satyen 14. Abulaish Muhammad 15. Acampora Giovanni 16. Acernese Fausto 17. Acharya Ayan 18. Achtner Wolfgang 19. Adachi Fuminori 20. Adamatzky Andrew 21. Adams K.J. 22. Adamson Kenneth 23. Adefila Kehinde 24. Adhyaru Dipak M. 25. Adorna Henry 26. Agarwal Deepam 27. Agarwal Arun 28. Agarwal Sanjit 29. Aggarwal Charu C. 30. Aggarwal Swati 31. Aguan Kripamoy 32. Agui Takeshi 33. Ahluwalia Madhu 34. Ahmad Tanvir 35. Ahmad Nesar 36. Ahmed Rafiq 37. Ahmed Rosina 38. Ahn Rennull M. C. 39. Ai Lingmei 40. Aidinis Vassilis 41. Airola Antti 42. Aizawa Akiko N. 43. Akbari Mohammad Ali 44. Akedo Naoya 45. Akhgar Babak 46. Akkermans Hans 47. Al-Bayatti Ali H. 48. Al-Dubaee Shawki A. 49. Al-Hmouz Ahmed 50. Al-Hmouz Rami 51. Al-Khateeb Tahseen 52. Al-Mayyan Waheeda 53. Al-Shenawy Nada M. 54. Al-Yami Maryam 55. Alam S. S. 56. Alam Mansoor 57. Alami Rachid 58. Albathan Mubarak 59. Alberg Dima 60. Alcalnull Rafael 61. Alcalnull-Fdez Jesnulls 62. Alcnullntara Otnullvio D. A. 63. Alfaro-Garc?a V?ctor 64. Alhazov Artiom 65. Alhimale Laila 66. -

![[Re]Viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]Visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1753/re-viewing-the-chinese-landscape-imaging-the-body-in-visible-in-shanshuihua-1061753.webp)

[Re]Viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]Visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫

[Re]viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫 Lim Chye Hong 林彩鳳 A thesis submitted to the University of New South Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Chinese Studies School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales Australia abstract This thesis, titled '[Re]viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫,' examines shanshuihua as a 'theoretical object' through the intervention of the present. In doing so, the study uses the body as an emblem for going beyond the surface appearance of a shanshuihua. This new strategy for interpreting shanshuihua proposes a 'Chinese' way of situating bodily consciousness. Thus, this study is not about shanshuihua in a general sense. Instead, it focuses on the emergence and codification of shanshuihua in the tenth and eleventh centuries with particular emphasis on the cultural construction of landscape via the agency of the body. On one level the thesis is a comprehensive study of the ideas of the body in shanshuihua, and on another it is a review of shanshuihua through situating bodily consciousness. The approach is not an abstract search for meaning but, rather, is empirically anchored within a heuristic and phenomenological framework. This framework utilises primary and secondary sources on art history and theory, sinology, medical and intellectual history, ii Chinese philosophy, phenomenology, human geography, cultural studies, and selected landscape texts. This study argues that shanshuihua needs to be understood and read not just as an image but also as a creative transformative process that is inevitably bound up with the body. -

Weaponry During the Period of Disunity in Imperial China with a Focus on the Dao

Weaponry During the Period of Disunity in Imperial China With a focus on the Dao An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty Of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE By: Bryan Benson Ryan Coran Alberto Ramirez Date: 04/27/2017 Submitted to: Professor Diana A. Lados Mr. Tom H. Thomsen 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 List of Figures 4 Individual Participation 7 Authorship 8 1. Abstract 10 2. Introduction 11 3. Historical Background 12 3.1 Fall of Han dynasty/ Formation of the Three Kingdoms 12 3.2 Wu 13 3.3 Shu 14 3.4 Wei 16 3.5 Warfare and Relations between the Three Kingdoms 17 3.5.1 Wu and the South 17 3.5.2 Shu-Han 17 3.5.3 Wei and the Sima family 18 3.6 Weaponry: 18 3.6.1 Four traditional weapons (Qiang, Jian, Gun, Dao) 18 3.6.1.1 The Gun 18 3.6.1.2 The Qiang 19 3.6.1.3 The Jian 20 3.6.1.4 The Dao 21 3.7 Rise of the Empire of Western Jin 22 3.7.1 The Beginning of the Western Jin Empire 22 3.7.2 The Reign of Empress Jia 23 3.7.3 The End of the Western Jin Empire 23 3.7.4 Military Structure in the Western Jin 24 3.8 Period of Disunity 24 4. Materials and Manufacturing During the Period of Disunity 25 2 Table of Contents (Cont.) 4.1 Manufacturing of the Dao During the Han Dynasty 25 4.2 Manufacturing of the Dao During the Period of Disunity 26 5. -

Jinfan Zhang the Tradition and Modern Transition of Chinese Law the Tradition and Modern Transition of Chinese Law

Jinfan Zhang The Tradition and Modern Transition of Chinese Law The Tradition and Modern Transition of Chinese Law Jinfan Zhang The Tradition and Modern Transition of Chinese Law Chief translator Zhang Lixin Other translators Yan Chen Li Xing Zhang Ye Xu Hongfen Jinfan Zhang China University of Political Science and Law Beijing , People’s Republic of China Sponsored by Chinese Fund for the Humanities and Social Sciences (本书获中华社会科学基金中华外译项目资助) ISBN 978-3-642-23265-7 ISBN 978-3-642-23266-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-23266-4 Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014931393 © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York *SUBJECT to GENERAL and SPECIFIC NOTES to THESE SCHEDULES* SUMMARY

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York Refco Capital Markets, LTD Case Number: 05-60018 *SUBJECT TO GENERAL AND SPECIFIC NOTES TO THESE SCHEDULES* SUMMARY OF AMENDED SCHEDULES An asterisk (*) found in schedules herein indicates a change from the Debtor's original Schedules of Assets and Liabilities filed December 30, 2005. Any such change will also be indicated in the "Amended" column of the summary schedules with an "X". Indicate as to each schedule whether that schedule is attached and state the number of pages in each. Report the totals from Schedules A, B, C, D, E, F, I, and J in the boxes provided. Add the amounts from Schedules A and B to determine the total amount of the debtor's assets. Add the amounts from Schedules D, E, and F to determine the total amount of the debtor's liabilities. AMOUNTS SCHEDULED NAME OF SCHEDULE ATTACHED NO. OF SHEETS ASSETS LIABILITIES OTHER YES / NO A - REAL PROPERTY NO 0 $0 B - PERSONAL PROPERTY YES 30 $6,002,376,477 C - PROPERTY CLAIMED AS EXEMPT NO 0 D - CREDITORS HOLDING SECURED CLAIMS YES 2 $79,537,542 E - CREDITORS HOLDING UNSECURED YES 2 $0 PRIORITY CLAIMS F - CREDITORS HOLDING UNSECURED NON- YES 356 $5,366,962,476 PRIORITY CLAIMS G - EXECUTORY CONTRACTS AND UNEXPIRED YES 2 LEASES H - CODEBTORS YES 1 I - CURRENT INCOME OF INDIVIDUAL NO 0 N/A DEBTOR(S) J - CURRENT EXPENDITURES OF INDIVIDUAL NO 0 N/A DEBTOR(S) Total number of sheets of all Schedules 393 Total Assets > $6,002,376,477 $5,446,500,018 Total Liabilities > UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York Refco Capital Markets, LTD Case Number: 05-60018 GENERAL NOTES PERTAINING TO SCHEDULES AND STATEMENTS FOR ALL DEBTORS On October 17, 2005 (the “Petition Date”), Refco Inc. -

A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture

A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture Edited by Antje Richter LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Acknowledgements ix List of Illustrations xi Abbreviations xiii About the Contributors xiv Introduction: The Study of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture 1 Antje Richter PART 1 Material Aspects of Chinese Letter Writing Culture 1 Reconstructing the Postal Relay System of the Han Period 17 Y. Edmund Lien 2 Letters as Calligraphy Exemplars: The Long and Eventful Life of Yan Zhenqing’s (709–785) Imperial Commissioner Liu Letter 53 Amy McNair 3 Chinese Decorated Letter Papers 97 Suzanne E. Wright 4 Material and Symbolic Economies: Letters and Gifts in Early Medieval China 135 Xiaofei Tian PART 2 Contemplating the Genre 5 Letters in the Wen xuan 189 David R. Knechtges 6 Between Letter and Testament: Letters of Familial Admonition in Han and Six Dynasties China 239 Antje Richter For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV vi Contents 7 The Space of Separation: The Early Medieval Tradition of Four-Syllable “Presentation and Response” Poetry 276 Zeb Raft 8 Letters and Memorials in the Early Third Century: The Case of Cao Zhi 307 Robert Joe Cutter 9 Liu Xie’s Institutional Mind: Letters, Administrative Documents, and Political Imagination in Fifth- and Sixth-Century China 331 Pablo Ariel Blitstein 10 Bureaucratic Influences on Letters in Middle Period China: Observations from Manuscript Letters and Literati Discourse 363 Lik Hang Tsui PART 3 Diversity of Content and Style section 1 Informal Letters 11 Private Letter Manuscripts from Early Imperial China 403 Enno Giele 12 Su Shi’s Informal Letters in Literature and Life 475 Ronald Egan 13 The Letter as Artifact of Sentiment and Legal Evidence 508 Janet Theiss 14 Infijinite Variations of Writing and Desire: Love Letters in China and Europe 546 Bonnie S. -

The Chinese Reader's Manual

@ William Frederick MAYERS THE CHINESE READER’S MANUAL The Chinese Reader's Manual à partir de : THE CHINESE READER‟S MANUAL A handbook of biographical, historical, mythological, and general literary reference par William Frederick MAYERS (1831-1878) American Presbiterian Mission Press, Shanghai, 1874. Réimpression : Literature House, Taipeh, 1964. Parties I et II (XXIV+360 pages), de XXIV+440 pages. Édition en format texte par Pierre Palpant www.chineancienne.fr décembre 2011 2 The Chinese Reader's Manual CONTENTS Preface Introduction Part A : Index of proper names A — C — F — H — I — J — K — L — M — N — O — P — S — T — W — Y Part B : Numerical categories Two — Three — Four — Five — Six — Seven — Eight — Nine — Ten — Twelve — Thirteen — Seventeen — Eighteen — Twenty-four — Twenty- eight — Thirty-two — Seventy-two — Hundred. 3 The Chinese Reader's Manual PREFACE @ p.III The title „CHINESE READER‟S MANUAL‟ has been given to the following work in the belief that it will be found useful in the hands of students of Chinese literature, by elucidating in its First Part many of the personal and historical allusions, and some portion at least of the conventional phraseology, which unite to form one of the chief difficulties of the language ; whilst in its remaining sections information of an equally essential nature is presented in a categorical shape. The wealth of illustration furnished to a Chinese writer by the records of his long-descended past is a feature which must be remarked at even the most elementary stage of acquaintance with the literature of the country. In every branch of composition, ingenious parallels and the introduction of borrowed phrases, considered elegant in proportion to their concise and recondite character, enjoy in Chinese style the same place of distinction that is accorded in European literature to originality of thought or novelty of diction. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Scribes in Early Imperial

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Scribes in Early Imperial China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Tsang Wing Ma Committee in charge: Professor Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, Chair Professor Luke S. Roberts Professor John W. I. Lee September 2017 The dissertation of Tsang Wing Ma is approved. ____________________________________________ Luke S. Roberts ____________________________________________ John W. I. Lee ____________________________________________ Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, Committee Chair July 2017 Scribes in Early Imperial China Copyright © 2017 by Tsang Wing Ma iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Professor Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, my advisor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, for his patience, encouragement, and teaching over the past five years. I also thank my dissertation committees Professors Luke S. Roberts and John W. I. Lee for their comments on my dissertation and their help over the years; Professors Xiaowei Zheng and Xiaobin Ji for their encouragement. In Hong Kong, I thank my former advisor Professor Ming Chiu Lai at The Chinese University of Hong Kong for his continuing support over the past fifteen years; Professor Hung-lam Chu at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University for being a scholar model to me. I am also grateful to Dr. Kwok Fan Chu for his kindness and encouragement. In the United States, at conferences and workshops, I benefited from interacting with scholars in the field of early China. I especially thank Professors Robin D. S. Yates, Enno Giele, and Charles Sanft for their comments on my research. Although pursuing our PhD degree in different universities in the United States, my friends Kwok Leong Tang and Shiuon Chu were always able to provide useful suggestions on various matters. -

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 116. Last Time, After Seven Tries, Zhuge Liang Had Finally

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 116. Last time, after seven tries, Zhuge Liang had finally convinced the Nan Man king Meng Huo to submit. With his mission accomplished, Zhuge Liang headed home, but his army ran into a roadblock at the River Lu (2), where apparently all the spirits of those killed in battle were stirring up trouble and making the river uncrossable. Zhuge Liang asked the locals what could be done about this problem, and they told him, “Just do what we did in the old days: Kill 49 people and offer their heads as a sacrifice, and the spirits will dissipate.” Uh, has anyone thought about the irony of killing people to appease the angry spirits of people who were killed? Anyone? Anyone? No? Well, how about we try not killing anybody this time. Instead of following the gruesome tradition, Zhuge Liang turned not to his executioners, but to his chefs. He asked the army cooks to slaughter some and horses and roll out some dough. They then made a bunch of buns stuffed with beef, lamb, horse meat, and the like. These buns were made to look like human heads, which is just freaky. And Zhuge Liang dubbed them Man Tou. Now that word has stuck through the ages and is now used to refer to Chinese steamed buns, though the present-day incarnation of what’s called Man Tou typically has no filling inside; it’s just all dough. Today, the Chinese buns that have fillings are called a different name, and they don’t look like human heads.