In Search of the Khutugtu's Monastery: the Site and Its Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Rivers of Mongolia

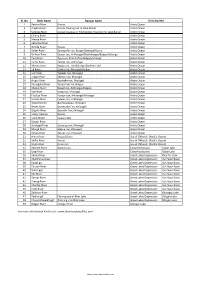

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

Key Sites for Key Sites for Conservation

Directory of Important Bird Areas in Mongolia: KEY SITES FOR CONSERVATION A project of In collaboration with With the support of Printing sponsored by Field surveys supported by Directory of Important Bird Areas in Mongolia: KEY SITES FOR CONSERVATION Editors: Batbayar Nyambayar and Natsagdorj Tseveenmyadag Major contributors: Ayurzana Bold Schagdarsuren Boldbaatar Axel Bräunlich Simba Chan Richard F. A. Grimmett and Andrew W. Tordoff This document is an output of the World Bank study Strengthening the Safeguard of Important Areas of Natural Habitat in North-East Asia,fi nanced by consultant trust funds from the government of Japan Ulaanbaatar, January 2009 An output of: The World Bank study Strengthening the Safeguard of Important Areas of Natural Habitat in North-East Asia,fi nanced by consultant trust funds from the government of Japan Implemented by: BirdLife International, the Wildlife Science and Conservation Center and the Institute of Biology of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences In collaboration with: Ministry of Nature, Environment and Tourism Supporting organisations: WWF Mongolia, WCS Mongolia Program and the National University of Mongolia Editors: Batbayar Nyambayar and Natsagdorj Tseveenmyadag Major contributors: Ayurzana Bold, Schagdarsuren Boldbaatar, Axel Bräunlich, Simba Chan, Richard F. A. Grimmett and Andrew W. Tordoff Maps: Dolgorjav Sanjmyatav, WWF Mongolia Cover illustrations: White-naped Crane Grus vipio, Dalmatian Pelican Pelecanus crispus, Whooper Swans Cygnus cygnus and hunters with Golden Eagles Aquila chrysaetos (Batbayar Nyambayar); Siberian Cranes Grus leucogeranus (Natsagdorj Tseveenmyadag); Saker Falcons Falco cherrug and Yellow-headed Wagtail Motacilla citreola (Gabor Papp). ISBN: 978-99929-0-752-5 Copyright: © BirdLife International 2009. All rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged Suggested citation: Nyambayar, B. -

Place”: Performance, Oral Tradition, and Improvization in the Hidden Temples of Mountain Altai

Oral Tradition, 27/2 (2012): 291-318 Sensing “Place”: Performance, Oral Tradition, and Improvization in the Hidden Temples of Mountain Altai Carole Pegg and Elizaveta Yamaeva Dedicated to Arzhan Mikhailovich Közörökov (1978-2012) 1. Introduction: Altai’s Ear The snow-capped Altai Mountain range runs from southern Siberia in the Russian Federation, southwards through West Mongolia, eastern Kazakhstan, and the Xinjiang autonomous region of Northwest China, before finally coming to rest in Southwest Mongolia. This essay is based on fieldwork undertaken in 2010 in that part of the Altai Mountains that in 1990 became the Republic of Altai, a unit of the Russian Federation.1 The Altaians, known previously as Kalmyks and Oirots, engage in a complex of spiritual beliefs and practices known locally as Ak Jang (“White Way”)2 and in academic literature as Burkhanism. Whether this movement was messianic, nationalist, or spiritual and whether it was a continuation of indigenous beliefs and practices or a syncretic mixture of local beliefs (Altai Jang), Buddhism, Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, and Orthodox Christianity have been argued 1 Dr. Pegg wishes to thank the World Oral Literature Project, University of Cambridge (2010), the Economic and Social Research Council (2003-07), and the British Academy (2002) for funding her field research in Altai, as well as the Gorno-Altaisk State University for facilitating that research. Special thanks go to Irene Aleksandrovna Tozyyakova for her help as research assistant and interpreter. Dr. Pegg is also grateful to the musicians, spiritual specialists, and Sary Bür communities of Altai who shared with her their valuable time. Thanks also go to Danil’ Mamyev, founder of the Üch Engmek (Ethno) Nature Park, and Chagat Almashev, Director of the Foundation for Sustainable Development of Altai (FSDA), who both helped with the practicalities of research. -

Mapuche Pantheon

MAPUCHE PANTHEON The Mapuches believed in two worlds: the natural world, made up of the earth with its people, and a supernatu- ral one which is magical and religious in the sky. The supernatural world is called Wenumapu, and it is a balanced region between the clouds and the universe. It is where gods, spirits and ancestors live. The Anka- wenu was a disorganized and chaotic space next to Wenumapu where evil spirits or Wekufes live. These cause suffering and harm to mankind. CHAU was the creator god of the Mapuche. He was also known as Nguenechèn, Father, the Sun, and Antü. HUEÑAUCA was an evil and fiery spirit who lived in the depths of the Osorno volcano. He produced fire and ruled over a court of beings that could not speak. There was often a male goat protecting the entrance to his cavern. KAI-KAI FILU was the evil sea serpent who carried two of Chau’s rebellious sons within him. Kai-Kai Filu was always planning to take power away from his father the creator. When he got mad he created tidal waves, floods and earth quakes by violently flapping his giant tale. KÜPUKA FUCHA and KÜPUKA KUSHE were the god and goddess of abundance. KUSHE means “witch”. This goddess was both the wife and mother of Chau (Nguenechèn) the creator god. She was also known as Moon, Blue Queen and Queen Maga. NAHUEL was a god in the shape of a tiger. PILLAN was the god of thunder as well as a fire spirit. He protected the elements and humans and was the creator of thunder and lightning. -

New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War

Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issue 16 New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War Translation and Introduction by Sergey Radchenko1 n a freezing November afternoon in Ulaanbaatar China and Russia fell under the Mongolian sword. However, (Ulan Bator), I climbed the Zaisan hill on the south- after being conquered in the 17th century by the Manchus, Oern end of town to survey the bleak landscape below. the land of the Mongols was divided into two parts—called Black smoke from gers—Mongolian felt houses—blanketed “Outer” and “Inner” Mongolia—and reduced to provincial sta- the valley; very little could be discerned beyond the frozen tus. The inhabitants of Outer Mongolia enjoyed much greater Tuul River. Chilling wind reminded me of the cold, harsh autonomy than their compatriots across the border, and after winter ahead. I thought I should have stayed at home after all the collapse of the Qing dynasty, Outer Mongolia asserted its because my pen froze solid, and I could not scribble a thing right to nationhood. Weak and disorganized, the Mongolian on the documents I carried up with me. These were records religious leadership appealed for help from foreign countries, of Mongolia’s perilous moves on the chessboard of giants: including the United States. But the first foreign troops to its strategy of survival between China and the Soviet Union, appear were Russian soldiers under the command of the noto- and its still poorly understood role in Asia’s Cold War. These riously cruel Baron Ungern who rode past the Zaisan hill in the documents were collected from archival depositories and pri- winter of 1921. -

Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe Romanization: KNAB 2012

Institute of the Estonian Language KNAB: Place Names Database 2012-10-11 Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe romanization: KNAB 2012 I. Consonant characters 1 ᦀ ’a 13 ᦌ sa 25 ᦘ pha 37 ᦤ da A 2 ᦁ a 14 ᦍ ya 26 ᦙ ma 38 ᦥ ba A 3 ᦂ k’a 15 ᦎ t’a 27 ᦚ f’a 39 ᦦ kw’a 4 ᦃ kh’a 16 ᦏ th’a 28 ᦛ v’a 40 ᦧ khw’a 5 ᦄ ng’a 17 ᦐ n’a 29 ᦜ l’a 41 ᦨ kwa 6 ᦅ ka 18 ᦑ ta 30 ᦝ fa 42 ᦩ khwa A 7 ᦆ kha 19 ᦒ tha 31 ᦞ va 43 ᦪ sw’a A A 8 ᦇ nga 20 ᦓ na 32 ᦟ la 44 ᦫ swa 9 ᦈ ts’a 21 ᦔ p’a 33 ᦠ h’a 45 ᧞ lae A 10 ᦉ s’a 22 ᦕ ph’a 34 ᦡ d’a 46 ᧟ laew A 11 ᦊ y’a 23 ᦖ m’a 35 ᦢ b’a 12 ᦋ tsa 24 ᦗ pa 36 ᦣ ha A Syllable-final forms of these characters: ᧅ -k, ᧂ -ng, ᧃ -n, ᧄ -m, ᧁ -u, ᧆ -d, ᧇ -b. See also Note D to Table II. II. Vowel characters (ᦀ stands for any consonant character) C 1 ᦀ a 6 ᦀᦴ u 11 ᦀᦹ ue 16 ᦀᦽ oi A 2 ᦰ ( ) 7 ᦵᦀ e 12 ᦵᦀᦲ oe 17 ᦀᦾ awy 3 ᦀᦱ aa 8 ᦶᦀ ae 13 ᦺᦀ ai 18 ᦀᦿ uei 4 ᦀᦲ i 9 ᦷᦀ o 14 ᦀᦻ aai 19 ᦀᧀ oei B D 5 ᦀᦳ ŭ,u 10 ᦀᦸ aw 15 ᦀᦼ ui A Indicates vowel shortness in the following cases: ᦀᦲᦰ ĭ [i], ᦵᦀᦰ ĕ [e], ᦶᦀᦰ ăe [ ∎ ], ᦷᦀᦰ ŏ [o], ᦀᦸᦰ ăw [ ], ᦀᦹᦰ ŭe [ ɯ ], ᦵᦀᦲᦰ ŏe [ ]. -

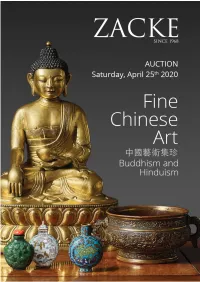

Catazacke 20200425 Bd.Pdf

Provenances Museum Deaccessions The National Museum of the Philippines The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University New York, USA The Monterey Museum of Art, USA The Abrons Arts Center, New York, USA Private Estate and Collection Provenances Justus Blank, Dutch East India Company Georg Weifert (1850-1937), Federal Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia Sir William Roy Hodgson (1892-1958), Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, OBE Jerrold Schecter, The Wall Street Journal Anne Marie Wood (1931-2019), Warwickshire, United Kingdom Brian Lister (19262014), Widdington, United Kingdom Léonce Filatriau (*1875), France S. X. Constantinidi, London, United Kingdom James Henry Taylor, Royal Navy Sub-Lieutenant, HM Naval Base Tamar, Hong Kong Alexandre Iolas (19071987), Greece Anthony du Boulay, Honorary Adviser on Ceramics to the National Trust, United Kingdom, Chairman of the French Porcelain Society Robert Bob Mayer and Beatrice Buddy Cummings Mayer, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago Leslie Gifford Kilborn (18951972), The University of Hong Kong Traudi and Peter Plesch, United Kingdom Reinhold Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria Sir Thomas Jackson (1841-1915), 1st Baronet, United Kingdom Richard Nathanson (d. 2018), United Kingdom Dr. W. D. Franz (1915-2005), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Josette and Théo Schulmann, Paris, France Neil Cole, Toronto, Canada Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald (19021982) Arthur Huc (1854-1932), La Dépêche du Midi, Toulouse, France Dame Eva Turner (18921990), DBE Sir Jeremy Lever KCMG, University -

A Study of the Pantheon Through Time Caitlin Williams

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2018 A Study of the Pantheon Through Time Caitlin Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Caitlin, "A Study of the Pantheon Through Time" (2018). Honors Theses. 1689. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1689 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study of the Pantheon Through Time By Caitlin Williams * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Classics UNION COLLEGE June, 2018 ABSTRACT WILLIAMS, CAITLIN A Study of the Pantheon Through Time. Department of Classics, June, 2018. ADVISOR: Hans-Friedrich Mueller. I analyze the Pantheon, one of the most well-preserVed buildings from antiquity, through time. I start with Agrippa's Pantheon, the original Pantheon that is no longer standing, which was built in 27 or 25 BC. What did it look like originally under Augustus? Why was it built? We then shift to the Pantheon that stands today, Hadrian-Trajan's Pantheon, which was completed around AD 125-128, and represents an example of an architectural reVolution. Was it eVen a temple? We also look at the Pantheon's conversion to a church, which helps explain why it is so well preserVed. -

Tuul River Mongolia

HEALTHY RIVERS FOR ALL Tuul River Basin Report Card • 1 TUUL RIVER MONGOLIA BASIN HEALTH 2019 REPORT CARD Tuul River Basin Report Card • 2 TUUL RIVER BASIN: OVERVIEW The Tuul River headwaters begin in the Lower As of 2018, 1.45 million people were living within Khentii mountains of the Khan Khentii mountain the Tuul River basin, representing 46% of Mongolia’s range (48030’58.9” N, 108014’08.3” E). The river population, and more than 60% of the country’s flows southwest through the capital of Mongolia, GDP. Due to high levels of human migration into Ulaanbaatar, after which it eventually joins the the basin, land use change within the floodplains, Orkhon River in Orkhontuul soum where the Tuul lack of wastewater treatment within settled areas, River Basin ends (48056’55.1” N, 104047’53.2” E). The and gold mining in Zaamar soum of Tuv aimag and Orkhon River then joins the Selenge River to feed Burenkhangai soum of Bulgan aimag, the Tuul River Lake Baikal in the Russian Federation. The catchment has emerged as the most polluted river in Mongolia. area is approximately 50,000 km2, and the river itself These stressors, combined with a growing water is about 720 km long. Ulaanbaatar is approximately demand and changes in precipitation due to global 470 km upstream from where the Tuul River meets warming, have led to a scarcity of water and an the Orkhon River. interruption of river flow during the spring. The Tuul River basin includes a variety of landscapes Although much research has been conducted on the including mountain taiga and forest steppe in water quality and quantity of the Tuul River, there is the upper catchment, and predominantly steppe no uniform or consistent assessment on the state downstream of Ulaanbaatar City. -

World Bank Document

WWF \ ORRI I) fKh K Public Disclosure Authorized AR@ 33100 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized XaTrHH; OCOHamxHMEHCYXBAATAP XaTI'HH OcopHaMxKHMFiH CYXBAATAP Public Disclosure Authorized MOHrOJI YJICbIH IHHHMJI3X YXAAHbI AIAAEMH X3JI 3OXHOJIbIH XYP33JI3H SACRED SITES OF MONGOLIA MOHFOAbIH TAXHAFAT YYA YCHbI CAHFIHHH CYaAP OPWBOH. 3MX3Tr3H 6ojioBcpyyn,K 3p,3M IUHH)CHJIF33HHR TakIi6ap, cyganraar yr4iiac3H XATIFHH OCOPHAMKIHMbIH CYXLAATAP PEXLAKTOP: ,UOKTOP, npo4eccop HI.XYP3JIEAATAP 93,R ,OKTOp m. COHHHBAIP X. B5IMBA)KAB Translation: B.ELBEGZAYA, Sh.GANBYAMBA, J.DUNN and T.LEWIS Ta]iapxa]¶ Acknowledgments: 3H3Xyy HOMbIr X3BJ WJI3X9JA,3J1XHHH BaHK, MoHroJIbIH BypxaH IIaliiHHTHbI TOB This publication has been made possible with the support of the Gandan Tegehilen (MEHIT) /FaHAaH T3r'HRj3H XHiiA/, lj3JIXHHiH BaHK-rowlaHqbIH 3acrHHH ra3pblH Monastery/ Center of Mongolian Buddhists and The World Bank-Netherlands XaMTbIH axnUuaraaHbI xeTeji6ep 60JIoH IHa1IlHH 6a BaiiraJIb XaMraan.nbIH Xo.u6oo Partnership Program, through a contract with the Alliance for Religions and Con- (IIIBXX) , Ij3JIXHHH BaHK 6a WWF (J3nIXHHH BafiraJlb XaMraajiax CaH) xaMTapcaH servation (ARC), and The World Bank-WWF Alliance for Forest Conservation OfiH HeeIgHHr xaMPaaJIax, TorTBoPToH amIHriax XeOTeJi6epHHH XYP33HA WWF and Sustainable Use, through a contract with WWF Mongolia and the assis- (J1A3nXHHH B,airaJlb XaMraaJlax CaH)-HiiH MoHPoJI Aaxb TOBIiOO 33p3r . 6a9JIXHfiyHayj caHxyyraRb Xamraaj1uiaxH CaHy.)-H H Ma OHi~rOp qaXb TOBquiar, T H tance of the following individuals working with these organizations: 6aRryynvmaryy,q caHxyyrHiiH TycjamIvaar y3yyJIC3H 6a 3Arm3p 6akryy:mara, TyyHHfi wJKMITHyyqa, TaiiapxaJi HJI3pXHHJIbe. MEHUIT/Fauda TqasiuAa Xu2i: ,LDizxuiMn Eaw?C For Gandan Monastery: ForARC: EIx xaM6aj,l. THomKaMuq TOHH YHTeH Hamba Lama D. Choijamts Baatar, Bazar )I3A A°OKTop III. -

ASIAN Philosophy of Protected Areas

ASIAN Philosophy of Protected Areas ! ! ! ! ! Asian Philosophy of Protected Areas Prepared by: Amran Hamzah Dylan Jefri Ong Dario Pampanga Centre for Innovative Planning and Development (CiPD) Faculty of Built Environment Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Skudai, Johor, Malaysia October 2013 ! ! ! ! ! Asian Philosophy of Protected Areas Acknowledgement This report has been prepared for the IUCN Biodiversity Conservation Programme, Asia, with the generous financial support of the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. The authors would like to thank both the above agencies for their continuous support through the duration of the research, especially to Scott Perkin, the Head of the IUCN Biodiversity Conservation Programme and Tanya Wattanakorn. Many individuals provided assistance in the form of providing information, comments and suggestions and we are indebted to them. We would like to single out the exceptional contributions given by Nigel Crawhall, Les Clark, Lawal Marafa, Robert Blasiak in giving us constructive comments and suggestions to improve the report. Thanks too to the team from the Centre for Innovative Planning and Development (CIPD), Universiti Teknologi Malaysia for carrying out the fieldwork at Kinabalu Park, Sabah and the subsequent analysis. Sabah Parks kindly provided assistance during our fieldwork and we are grateful to its Director, Mr. Paul Basintal and Mr. Maipol Spait for their continuous help. Finally a big thank you to Yong Jia Yaik and Abdullah Lahat for their technical and editorial assistance. Amran Hamzah Dylan -

An Introduction to Indic Scripts

An Introduction to Indic Scripts Richard Ishida W3C [email protected] HTML version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.html PDF version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.pdf Introduction This paper provides an introduction to the major Indic scripts used on the Indian mainland. Those addressed in this paper include specifically Bengali, Devanagari, Gujarati, Gurmukhi, Kannada, Malayalam, Oriya, Tamil, and Telugu. I have used XHTML encoded in UTF-8 for the base version of this paper. Most of the XHTML file can be viewed if you are running Windows XP with all associated Indic font and rendering support, and the Arial Unicode MS font. For examples that require complex rendering in scripts not yet supported by this configuration, such as Bengali, Oriya, and Malayalam, I have used non- Unicode fonts supplied with Gamma's Unitype. To view all fonts as intended without the above you can view the PDF file whose URL is given above. Although the Indic scripts are often described as similar, there is a large amount of variation at the detailed implementation level. To provide a detailed account of how each Indic script implements particular features on a letter by letter basis would require too much time and space for the task at hand. Nevertheless, despite the detail variations, the basic mechanisms are to a large extent the same, and at the general level there is a great deal of similarity between these scripts. It is certainly possible to structure a discussion of the relevant features along the same lines for each of the scripts in the set.