Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grammatica Et Verba Glamor and Verve

“GippertOVprint” — 2014/4/24 — 22:14 — page 81 —#1 Grammatica et verba Glamor and verve Studies in South Asian, historical, and Indo-European linguistics in honor of Hans Henrich Hock on the occasion of his seventy-fifth birthday edited by Shu-Fen Chen and Benjamin Slade Beech Stave Press Ann Arbor New York • “GippertOVprint” — 2014/4/24 — 22:14 — page 82 —#2 © Beech Stave Press, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Typeset with LATEX using the Galliard typeface designed by Matthew Carter and Greek Old Face by Ralph Hancock. The typeface on the cover is Post Hock by Steve Peter. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Grammatica et verba : glamor and verve : studies in South Asian, historical, and Indo- European linguistics in honor of Hans Henrich Hock on the occasion of his seventy- fifth birthday / edited by Shu-Fen Chen and Benjamin Slade. pages cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN ---- (alk. paper) . Indo-European languages. Lexicography. Historical linguistics. I. Hock, Hans Henrich, - honoree. II. Chen, Shu-Fen, editor of compilation. III. Slade, Ben- jamin, editor of compilation. –dc Printed in the United States of America “GippertOVprint” — 2014/4/24 — 22:14 — page 83 —#3 TableHHHHHH ofHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH ContentsHHHHHHHHHHHH Preface . vii Bibliography of Hans Henrich Hock . ix List of Contributors . xxi , Traces of Archaic Human Language Structure Anvita Abbi in the Great Andamanese Language. , A Study of Punctuation Errors in the Chinese Diamond Sutra Shu-Fen Chen Based on Sanskrit Texts . -

A Practical Sanskrit Introductory

A Practical Sanskrit Intro ductory This print le is available from ftpftpnacaczawiknersktintropsjan Preface This course of fteen lessons is intended to lift the Englishsp eaking studentwho knows nothing of Sanskrit to the level where he can intelligently apply Monier DhatuPat ha Williams dictionary and the to the study of the scriptures The rst ve lessons cover the pronunciation of the basic Sanskrit alphab et Devanagar together with its written form in b oth and transliterated Roman ash cards are included as an aid The notes on pronunciation are largely descriptive based on mouth p osition and eort with similar English Received Pronunciation sounds oered where p ossible The next four lessons describ e vowel emb ellishments to the consonants the principles of conjunct consonants Devanagar and additions to and variations in the alphab et Lessons ten and sandhi eleven present in grid form and explain their principles in sound The next three lessons p enetrate MonierWilliams dictionary through its four levels of alphab etical order and suggest strategies for nding dicult words The artha DhatuPat ha last lesson shows the extraction of the from the and the application of this and the dictionary to the study of the scriptures In addition to the primary course the rst eleven lessons include a B section whichintro duces the student to the principles of sentence structure in this fully inected language Six declension paradigms and class conjugation in the present tense are used with a minimal vo cabulary of nineteen words In the B part of -

The Festvox Indic Frontend for Grapheme-To-Phoneme Conversion

The Festvox Indic Frontend for Grapheme-to-Phoneme Conversion Alok Parlikar, Sunayana Sitaram, Andrew Wilkinson and Alan W Black Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, USA aup, ssitaram, aewilkin, [email protected] Abstract Text-to-Speech (TTS) systems convert text into phonetic pronunciations which are then processed by Acoustic Models. TTS frontends typically include text processing, lexical lookup and Grapheme-to-Phoneme (g2p) conversion stages. This paper describes the design and implementation of the Indic frontend, which provides explicit support for many major Indian languages, along with a unified framework with easy extensibility for other Indian languages. The Indic frontend handles many phenomena common to Indian languages such as schwa deletion, contextual nasalization, and voicing. It also handles multi-script synthesis between various Indian-language scripts and English. We describe experiments comparing the quality of TTS systems built using the Indic frontend to grapheme-based systems. While this frontend was designed keeping TTS in mind, it can also be used as a general g2p system for Automatic Speech Recognition. Keywords: speech synthesis, Indian language resources, pronunciation 1. Introduction in models of the spectrum and the prosody. Another prob- lem with this approach is that since each grapheme maps Intelligible and natural-sounding Text-to-Speech to a single “phoneme” in all contexts, this technique does (TTS) systems exist for a number of languages of the world not work well in the case of languages that have pronun- today. However, for low-resource, high-population lan- ciation ambiguities. We refer to this technique as “Raw guages, such as languages of the Indian subcontinent, there Graphemes.” are very few high-quality TTS systems available. -

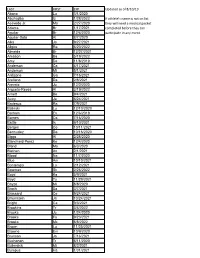

LAST FIRST EXP Updated As of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If Athlete's Name Is Not on List Acevedo Jr

LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If athlete's name is not on list Acevedo Jr. Ma 2/27/2020 they will need a medical packet Adams Br 1/17/2021 completed before they can Aguilar Br 12/6/2020 participate in any event. Aguilar-Soto Al 8/7/2020 Alka Ja 9/27/2021 Allgire Ra 6/20/2022 Almeida Br 12/27/2021 Amason Ba 5/19/2022 Amy De 11/8/2019 Anderson Ca 4/17/2021 Anderson Mi 5/1/2021 Ardizone Ga 7/16/2021 Arellano Da 2/8/2021 Arevalo Ju 12/2/2020 Argueta-Reyes Al 3/19/2022 Arnett Be 9/4/2021 Autry Ja 6/24/2021 Badeaux Ra 7/9/2021 Balinski Lu 12/10/2020 Barham Ev 12/6/2019 Barnes Ca 7/16/2020 Battle Is 9/10/2021 Bergen Co 10/11/2021 Bermudez Da 10/16/2020 Biggs Al 2/28/2020 Blanchard-Perez Ke 12/4/2020 Bland Ma 6/3/2020 Blethen An 2/1/2021 Blood Na 11/7/2020 Blue Am 10/10/2021 Bontempo Lo 2/12/2021 Bowman Sk 2/26/2022 Boyd Ka 5/9/2021 Boyd Ty 11/29/2021 Boyzo Mi 8/8/2020 Brach Sa 3/7/2021 Brassard Ce 9/24/2021 Braunstein Ja 10/24/2021 Bright Ca 9/3/2021 Brookins Tr 3/4/2022 Brooks Ju 1/24/2020 Brooks Fa 9/23/2021 Brooks Mc 8/8/2022 Brown Lu 11/25/2021 Browne Em 10/9/2020 Brunson Jo 7/16/2021 Buchanan Tr 6/11/2020 Bullerdick Mi 8/2/2021 Bumpus Ha 1/31/2021 LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Burch Co 11/7/2020 Burch Ma 9/9/2021 Butler Ga 5/14/2022 Byers Je 6/14/2021 Cain Me 6/20/2021 Cao Tr 11/19/2020 Carlson Be 5/29/2021 Cerda Da 3/9/2021 Ceruto Ri 2/14/2022 Chang Ia 2/19/2021 Channapati Di 10/31/2021 Chao Et 8/20/2021 Chase Em 8/26/2020 Chavez Fr 6/13/2020 Chavez Vi 11/14/2021 Chidambaram Ga 10/13/2019 -

Kharosthi Manuscripts: a Window on Gandharan Buddhism*

KHAROSTHI MANUSCRIPTS: A WINDOW ON GANDHARAN BUDDHISM* Andrew GLASS INTRODUCTION In the present article I offer a sketch of Gandharan Buddhism in the centuries around the turn of the common era by looking at various kinds of evidence which speak to us across the centuries. In doing so I hope to shed a little light on an important stage in the transmission of Buddhism as it spread from India, through Gandhara and Central Asia to China, Korea, and ultimately Japan. In particular, I will focus on the several collections of Kharo~thi manuscripts most of which are quite new to scholarship, the vast majority of these having been discovered only in the past ten years. I will also take a detailed look at the contents of one of these manuscripts in order to illustrate connections with other text collections in Pali and Chinese. Gandharan Buddhism is itself a large topic, which cannot be adequately described within the scope of the present article. I will therefore confine my observations to the period in which the Kharo~thi script was used as a literary medium, that is, from the time of Asoka in the middle of the third century B.C. until about the third century A.D., which I refer to as the Kharo~thi Period. In addition to looking at the new manuscript materials, other forms of evidence such as inscriptions, art and architecture will be touched upon, as they provide many complementary insights into the Buddhist culture of Gandhara. The travel accounts of the Chinese pilgrims * This article is based on a paper presented at Nagoya University on April 22nd 2004. -

ART XVI.—On the Identity of Xandrames and Krananda

447 ART XVI.—On the Identity of Xandrames and Krananda. By EDWARD THOMAS, ESQ. AT the meeting of the Royal Asiatic Society, on the 21st Nov., 1864,1 undertook the task of establishing the identity of the Xandrames of Diodorus Siculus and Quintus Curtius, the undesignated king of the Gangetic provinces of other Classic Authors—with the potentate whose name appears on a very extensive series of local mintages under the bilingual Bactrian and Indo-Pali form of Krananda. With the very open array of optional readings of the name afforded by the Greek, Latin, Arabic, or Persian tran- scriptions, I need scarcely enter upon any vindication for con- centrating the whole cifcle of misnomers in the doubly autho- ritative version the coins have perpetuated: my endeavours will be confined to sustaining the reasonable probability of the contemporaneous existence of Alexander the Great and the Indian Krananda; to exemplifying the singularly appro- priate geographical currency and abundance of the coins themselves; and lastly to recapitulating the curious evidences bearing upon Krananda's individuality, supplied by indi- genous annals, and their strange coincidence with the legends preserved by the conterminous Persian epic and prose writers, occasionally reproduced by Arab translators, who, however, eventually sought more accurate knowledge from purely Indian sources. In the course of this inquiry, I shall be in a position to show, that Krananda was the prominent representative of the regnant fraternity of the " nine Nandas," and his coins, in their symbolic devices, will demonstrate for us, what no written history, home or foreign, has as yet explicitly de- clared, that the Nandas were Buddhists. -

The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes

Portland State University PDXScholar Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Fariborz Maseeh Department of Mathematics Publications and Presentations and Statistics 3-2018 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hu Sun University of Macau Christine Chambris Université de Cergy-Pontoise Judy Sayers Stockholm University Man Keung Siu University of Hong Kong Jason Cooper Weizmann Institute of Science SeeFollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Sun X.H. et al. (2018) The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes. In: Bartolini Bussi M., Sun X. (eds) Building the Foundation: Whole Numbers in the Primary Grades. New ICMI Study Series. Springer, Cham This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Authors Xu Hu Sun, Christine Chambris, Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper, Jean-Luc Dorier, Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued, Eva Thanheiser, Nadia Azrou, Lynn McGarvey, Catherine Houdement, and Lisser Rye Ejersbo This book chapter is available at PDXScholar: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac/253 Chapter 5 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hua Sun , Christine Chambris Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper , Jean-Luc Dorier , Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued , Eva Thanheiser , Nadia Azrou , Lynn McGarvey , Catherine Houdement , and Lisser Rye Ejersbo 5.1 Introduction Mathematics learning and teaching are deeply embedded in history, language and culture (e.g. -

Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe Romanization: KNAB 2012

Institute of the Estonian Language KNAB: Place Names Database 2012-10-11 Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe romanization: KNAB 2012 I. Consonant characters 1 ᦀ ’a 13 ᦌ sa 25 ᦘ pha 37 ᦤ da A 2 ᦁ a 14 ᦍ ya 26 ᦙ ma 38 ᦥ ba A 3 ᦂ k’a 15 ᦎ t’a 27 ᦚ f’a 39 ᦦ kw’a 4 ᦃ kh’a 16 ᦏ th’a 28 ᦛ v’a 40 ᦧ khw’a 5 ᦄ ng’a 17 ᦐ n’a 29 ᦜ l’a 41 ᦨ kwa 6 ᦅ ka 18 ᦑ ta 30 ᦝ fa 42 ᦩ khwa A 7 ᦆ kha 19 ᦒ tha 31 ᦞ va 43 ᦪ sw’a A A 8 ᦇ nga 20 ᦓ na 32 ᦟ la 44 ᦫ swa 9 ᦈ ts’a 21 ᦔ p’a 33 ᦠ h’a 45 ᧞ lae A 10 ᦉ s’a 22 ᦕ ph’a 34 ᦡ d’a 46 ᧟ laew A 11 ᦊ y’a 23 ᦖ m’a 35 ᦢ b’a 12 ᦋ tsa 24 ᦗ pa 36 ᦣ ha A Syllable-final forms of these characters: ᧅ -k, ᧂ -ng, ᧃ -n, ᧄ -m, ᧁ -u, ᧆ -d, ᧇ -b. See also Note D to Table II. II. Vowel characters (ᦀ stands for any consonant character) C 1 ᦀ a 6 ᦀᦴ u 11 ᦀᦹ ue 16 ᦀᦽ oi A 2 ᦰ ( ) 7 ᦵᦀ e 12 ᦵᦀᦲ oe 17 ᦀᦾ awy 3 ᦀᦱ aa 8 ᦶᦀ ae 13 ᦺᦀ ai 18 ᦀᦿ uei 4 ᦀᦲ i 9 ᦷᦀ o 14 ᦀᦻ aai 19 ᦀᧀ oei B D 5 ᦀᦳ ŭ,u 10 ᦀᦸ aw 15 ᦀᦼ ui A Indicates vowel shortness in the following cases: ᦀᦲᦰ ĭ [i], ᦵᦀᦰ ĕ [e], ᦶᦀᦰ ăe [ ∎ ], ᦷᦀᦰ ŏ [o], ᦀᦸᦰ ăw [ ], ᦀᦹᦰ ŭe [ ɯ ], ᦵᦀᦲᦰ ŏe [ ]. -

Sanskrit Alphabet

Sounds Sanskrit Alphabet with sounds with other letters: eg's: Vowels: a* aa kaa short and long ◌ к I ii ◌ ◌ к kii u uu ◌ ◌ к kuu r also shows as a small backwards hook ri* rri* on top when it preceeds a letter (rpa) and a ◌ ◌ down/left bar when comes after (kra) lri lree ◌ ◌ к klri e ai ◌ ◌ к ke o au* ◌ ◌ к kau am: ah ◌ं ◌ः कः kah Consonants: к ka х kha ga gha na Ê ca cha ja jha* na ta tha Ú da dha na* ta tha Ú da dha na pa pha º ba bha ma Semivowels: ya ra la* va Sibilants: sa ш sa sa ha ksa** (**Compound Consonant. See next page) *Modern/ Hindi Versions a Other ऋ r ॠ rr La, Laa (retro) औ au aum (stylized) ◌ silences the vowel, eg: к kam झ jha Numero: ण na (retro) १ ५ ॰ la 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 @ Davidya.ca Page 1 Sounds Numero: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 910 १॰ ॰ १ २ ३ ४ ६ ७ varient: ५ ८ (shoonya eka- dva- tri- catúr- pancha- sás- saptán- astá- návan- dásan- = empty) works like our Arabic numbers @ Davidya.ca Compound Consanants: When 2 or more consonants are together, they blend into a compound letter. The 12 most common: jna/ tra ttagya dya ddhya ksa kta kra hma hna hva examples: for a whole chart, see: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/devanagari_conjuncts.php that page includes a download link but note the site uses the modern form Page 2 Alphabet Devanagari Alphabet : к х Ê Ú Ú º ш @ Davidya.ca Page 3 Pronounce Vowels T pronounce Consonants pronounce Semivowels pronounce 1 a g Another 17 к ka v Kit 42 ya p Yoga 2 aa g fAther 18 х kha v blocKHead -

Indic Loanwords In Tocharian B, Local Markedness, And The Animacy

Indic Loanwords in Tocharian B, Local Markedness, and the Animacy Hierarchy Francesco Burroni and Michael Weiss (Department of Linguistics, Cornell University) A question that is rarely addressed in the literature devoted to Language Contact is: how are nominal forms borrowed when the donor and the recipient language both possess rich inflectional morphology? Can nominal forms be borrowed from and in different cases? What are the decisive factors shaping the borrowing scenario? In this paper, we frame this question from the angle of a case study involving two ancient Indo-European languages: Tocharian and Indic (Sanskrit, Prakrit(s)). Most studies dedicated to the topic of loanwords in Tocharian B (henceforth TB) have focused on borrowings from Iranian (e.g. Tremblay 2005), but little attention has been so far devoted to forms borrowed from Indic, perhaps because they are considered uninteresting. We argue that such forms, however, are of interest for the study of Language Contact. A remarkable feature of Indic borrowings into TB is that a-stems are borrowed in TB as e-stems when denoting animate referents, but as consonant (C-)stems when denoting inanimate referents, a distribution that was noticed long ago by Mironov (1928, following Staёl-Holstein 1910:117 on Uyghur). In the literature, however, one finds no reaction to Mironov’s idea. By means of a systematic study of all the a-stems borrowed from Indic into TB, we argue that the trait [+/- animate] of the referent is, in fact, a very good predictor of the TB shape of the borrowing, e.g. male personal names from Skt. -

The Personal Name Here Is Again Obscure. At

342 THE FIRST ARAMAIC INSCRIPTION FROM INDIA 1. 10 : " his conduct " ? 1. 11 : " and also his sons." 1. 12 : the personal name here is again obscure. At the end of the line are traces of the right-hand side of a letter, which might be samekh or beth; if we accept the former, it is possible to vocalize as Pavira-ram, i.e. Pavira-rdja, corresponding to the Sanskrit Pravira- rdja. The name Pravira is well known in epos, and might well be borne by a real man ; and the change of a sonant to a surd consonant, such as that of j to «, is quite common in the North-West dialects. L. D. BARNETT. THE FIRST ARAMAIC INSCRIPTION FROM INDIA I must thank Mr. F. W. Thomas for his great kindness in sending me the photograph taken by Sir J. H. Marshall, and also Dr. Barnett for letting me see his tracing and transliteration. The facsimile is made from the photo- graph, which is as good as it can be. Unfortunately, on the original, the letters are as white as the rest of the marble, and it was necessary to darken them in order to obtain a photograph. This process inti'oduces an element of uncertainty, since in some cases part of a line may have escaped, and in others an accidental scratch may appear as part of a letter. Hence the following passages are more or less doubtful: line 4, 3PI; 1. 6, Tpfl; 1. 8, "123 and y\; 1. 9, the seventh and ninth letters; 1. 10, ID; 1. -

192. Great Stupa at Sanchi Madhya Pradesh, India. Buddhist, Maurya

192. Great Stupa at Sanchi Madhya Pradesh, India. Buddhist, Maurya, late Sunga Dynasty. c. 300 B.C.E. – 100 C.E. Stone masonry, sandstone on dome The Great Stupa at Sanchi is the oldest stone structure in India[1] and was originally commissioned by the emperor Ashoka the Great in the 3rd century BCE built over the relics of the Buddha It was crowned by the chatra, a parasol-like structure symbolising high rank, which was intended to honour and shelter the relics 54 feet tall and 120 feet in diameter The construction work of this stupa was overseen by Ashoka's wife, Devi herself, who was the daughter of a merchant of Vidisha. Sanchi was also her birthplace as well as the venue of her and Ashoka's wedding. In the 1st century BCE, four elaborately carved toranas (ornamental gateways) and a balustrade encircling the entire structure were added With its many tiers it was a symbol of the dharma, the Wheel of the Law. The dome was set on a high circular drum meant for circumambulation, which could be accessed via a double staircase Built during many different dynasties . An inscription records the gift of one of the top architraves of the Southern Gateway by the artisans of the Satavahana king Satakarni: o "Gift of Ananda, the son of Vasithi, the foreman of the artisans of rajan Siri Satakarni".[ o Although made of stone, they were carved and constructed in the manner of wood and the gateways were covered with narrative sculptures. They showed scenes from the life of the Buddha integrated with everyday events that would be familiar to the onlookers and so make it easier for them to understand the Buddhist creed as relevant to their lives At Sanchi and most other stupas the local population donated money for the embellishment of the stupa to attain spiritual merit.