Civil War Finance: Lessons for Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Public Option in Housing Finance

The Public Option in Housing Finance Adam J. Levitin†* and Susan M. Wachter** The U.S. housing finance system presents a conundrum for the scholar of regulation because it defies description using the traditional regulatory vocabulary of command-and-control, taxation, subsidies, cap-and-trade permits, and litigation. Instead, since the New Deal, the housing finance market has been regulated primarily by government participation in the market through a panoply of institutions. The government’s participation in the market has shaped the nature of the products offered in the market. We term this form of regulation “public option” regulation. This Article presents a case study of this “public option” as a regulatory mode. It explains the public option’s rise as a governmental gap-filling response to market failures. The public option, however, took on a life of its own as the federal government undertook financial innovations that the private market had eschewed, in particular the development of the “American mortgage” — a long-term, fixed-rate fully amortizing mortgage. These innovations were trend-setting and set the tone for entire housing finance market, serving as functional regulation. The public option was never understood as a regulatory system due to its ad hoc nature. As a result, its integrity was not protected. Key parts of the system were privatized without a substitution of alternative regulatory measures. The consequence was a return to the very market failures that led to the public option in the first place, followed by another round of ad hoc public options in housing finance. This history suggests that an † Copyright © 2013 Adam J. -

Economics During the Lincoln Administration

4-15 Economics 1 of 4 A Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy ECONOMICS DURING THE LINCOLN ADMINISTRATION War Debt . Increased by about $2 million per day by 1862 . Secretary of the Treasury Chase originally sought to finance the war exclusively by borrowing money. The high costs forced him to include taxes in that plan as well. Loans covered about 65% of the war debt. With the help of Jay Cooke, a Philadelphia banker, Chase developed a war bond system that raised $3 billion and saw a quarter of middle class Northerners buying war bonds, setting the precedent that would be followed especially in World War II to finance the war. Morrill Tariff Act (1861) . Proposed by Senator Justin S. Morrill of Vermont to block imported goods . Supported by manufacturers, labor, and some commercial farmers . Brought in about $75 million per year (without the Confederate states, this was little more than had been brought in the 1850s) Revenue Act of 1861 . Restored certain excise tax . Levied a 3% tax on personal incomes higher than $800 per year . Income tax first collected in 1862 . First income tax in U. S. history The Legal Tender Act (1862) . Issued $150 million in treasury notes that came to be called greenbacks . Required that these greenbacks be accepted as legal tender for all debts, public and private (except for interest payments on federal bonds and customs duties) . Investors could buy bonds with greenbacks but acquire gold as interest United States Note (Greenback). EarthLink.net. 18 July 2008 <http://home.earthlink.net/~icepick119/page11.html> Revenue Act of 1862 Office of Curriculum & Instruction/Indiana Department of Education 09/08 This document may be duplicated and distributed as needed. -

Download (Pdf)

VOLUME 83 • NUMBER 12 • DECEMBER 1997 FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM, WASHINGTON, D.C. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Joseph R. Coyne, Chairman • S. David Frost • Griffith L. Garwood • Donald L. Kohn • J. Virgil Mattingly, Jr. • Michael J. Prell • Richard Spillenkothen • Edwin M. Truman The Federal Reserve Bulletin is issued monthly under the direction of the staff publications committee. This committee is responsible for opinions expressed except in official statements and signed articles. It is assisted by the Economic Editing Section headed by S. Ellen Dykes, the Graphics Center under the direction of Peter G. Thomas, and Publications Services supervised by Linda C. Kyles. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Table of Contents 947 TREASURY AND FEDERAL RESERVE OPEN formance can improve investor and counterparty MARKET OPERATIONS decisions, thus improving market discipline on banking organizations and other companies, During the third quarter of 1997, the dollar before the Subcommittee on Capital Markets, appreciated 5.0 percent against the Japanese yen Securities and Government Sponsored Enter- and 0.8 percent against the German mark. On a prises of the House Committee on Banking and trade-weighted basis against other Group of Ten Financial Services, October 1, 1997. currencies, the dollar appreciated 1.4 percent. The U.S. monetary authorities did not undertake 96\ Theodore E. Allison, Assistant to the Board of any intervention in the foreign exchange mar- Governors for Federal Reserve System Affairs, kets during the quarter. reports on the Federal Reserve's plans for deal- ing with some new-design $50 notes that 953 STAFF STUDY SUMMARY were imperfectly printed, including the Federal Reserve's view of the quality and quantity of In The Cost of Implementing Consumer Finan- $50 notes currently being produced by the cial Regulations, the authors present results for Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the options U.S. -

RESTORING the LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E

COPYRIGHT © 2017 VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW ASSOCIATION RESTORING THE LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E. Hickman* & Gerald Kerska† Should Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents be eligible for pre-enforcement judicial review? The D.C. Circuit’s 2015 decision in Florida Bankers Ass’n v. U.S. Department of the Treasury puts its interpretation of the Anti-Injunction Act at odds with both general administrative law norms in favor of pre-enforcement review of final agency action and also the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the nearly identical Tax Injunction Act. A 2017 federal district court decision in Chamber of Commerce v. IRS, appealable to the Fifth Circuit, interprets the Anti-Injunction Act differently and could lead to a circuit split regarding pre-enforcement judicial review of Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents. Other cases interpreting the Anti-Injunction Act more generally are fragmented and inconsistent. In an effort to gain greater understanding of the Anti-Injunction Act and its role in tax administration, this Article looks back to the Anti- Injunction Act’s origin in 1867 as part of Civil War–era revenue legislation and the evolution of both tax administrative practices and Anti-Injunction Act jurisprudence since that time. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1684 I. A JURISPRUDENTIAL MESS, AND WHY IT MATTERS ...................... 1688 A. Exploring the Doctrinal Tensions.......................................... 1690 1. Confused Anti-Injunction Act Jurisprudence .................. 1691 2. The Administrative Procedure Act’s Presumption of Reviewability ................................................................... 1704 3. The Tax Injunction Act .................................................... 1707 B. Why the Conflict Matters ....................................................... 1712 * Distinguished McKnight University Professor and Harlan Albert Rogers Professor in Law, University of Minnesota Law School. -

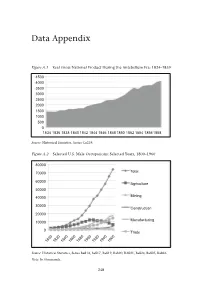

Data Appendix

Data Appendix Figure A.1 Real Gross National Product During the Antebellum Era: 1834–1859 4500 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 1834 1836 1838 1840 1842 1844 1846 1848 1850 1852 1854 18561858 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ca219. Figure A.2 Selected U.S. Male Occupations: Selected Years, 1800–1960 80000 70000 Total 60000 Agriculture 50000 40000 Mining 30000 Construction 20000 Manufacturing 10000 0 Trade 1800 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 Source: Historical Statistics, Series Ba814, Ba817, Ba819, Ba820, BA821, Ba824, Ba825, Ba826. Note: In thousands. 248 Source Source Note Source Figure A.5 Figure A.4 Figure A.3 : ThisistheSchwert’sIndexofCommonStock. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesAa36,Aa46, Aa56. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCh411. : HistoricalStatistics,SeriesCj979. 100000000 150000000 200000000 250000000 300000000 100000 120000 10 12 14 16 50000000 20000 40000 60000 80000 0 2 4 6 8 0 1802 0 U.S. PopulationforSelectedYears:1790–1990 Total NumberofU.S.BusinessFailures:1857–1997 1805 Stock IndexDuringtheAntebellumEra:1802–1870 1857 1790 1830 1860 1890 1920 1950 1990 1808 1863 1869 1811 1875 1814 1881 1817 1887 1820 1893 1823 1899 1826 1905 1829 1911 1832 1917 1835 1923 1838 1929 1841 1935 1941 1844 1947 1847 1953 1850 1959 1853 Total RuralPopulation Total UrbanPopulation Total Population Total 1965 1856 Data Appendix 1971 1859 1977 1862 1983 1865 1989 1995 1868 249 Note Source Note Source Figure A.8 up totheGreatDepression:1869–1929 Figure A.7 250 Source: Figure A.6 : ThisistheIndustrialsIndex. : ThisdataisfromGallman-Kuznetsestimationandin1929dollars. -

The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price Lauren E

Maryland Law Review Volume 65 | Issue 3 Article 3 Decisionmaking and the Limits of Disclosure: The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price Lauren E. Willis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Banking and Finance Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Lauren E. Willis, Decisionmaking and the Limits of Disclosure: The Problem of Predatory Lending: Price, 65 Md. L. Rev. 707 (2006) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol65/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARYLAND LAW REVIEW VOLUME 65 2006 NUMBER 3 © Copyright Maryland Law Review 2006 Articles DECISIONMAKING AND THE LIMITS OF DISCLOSURE: THE PROBLEM OF PREDATORY LENDING: PRICE LAUREN E. WILLIS* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 709 I. PREDATORY LENDING AND THE HOME LOAN MARKET ...... 715 A. The Home Lending Revolution ........................ 715 1. The Twentieth Century Marketplace: Standardized Terms, Limited and Advertised Prices, and Low Risk. 715 2. The Brave New World of ProliferatingProducts, Price, and R isk ........................................ 718 3. Evidence of Predatory Home Lending ............... 729 B. A New Definition of Predatory Lending ................. 735 II. FEDERAL LAW REGULATING THE PRICING OF HOME- SECURED LOANS: DISCLOSURE AS PANACEA ................ 741 A. The Rational Actor Decisionmaker Model ............... 741 B. CurrentFederal Law .................................. 743 C. Even a Rational Actor Could Not Use the Federal Disclosures to Price Shop in Today's Marketplace ....... -

The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed

Economic Quarterly— Volume 100, Number 2— Second Quarter 2014— Pages 159–181 The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed Robert L. Hetzel ilton Friedman (1982, 103) wrote: “In our book on U.S. mon- etary history, Anna Schwartz and I found it possible to use M one sentence to describe the central principle followed by the Federal Reserve System from the time it began operations in 1914 to 1952. That principle, to quote from our book, is: ‘Ifthe ‘money market’ is properly managed so as to avoid the unproductive use of credit and to assure the availability of credit for productive use, then the money stock will take care of itself.’” For Friedman, the reference to “the money stock”was synonymous with “the price level.”1 How did American monetary experience and debate in the 19th century give rise to these “real bills” views as a guide to Fed policy in the pre-World War II period? As distilled in the real bills doctrine, the founders of the Fed under- stood the Federal Reserve System as a decentralized system of reserve depositories that would allow the expansion and contraction of currency and credit based on discounting member-bank paper that originated out of productive activity. By discounting these “real bills,”the short- term loans that …nanced trade and goods in the process of production, policymakers ful…lled their responsibilities as they understood them. That is, they would provide the reserves required to accommodate the “legitimate,” nonspeculative, demands for credit.2 In so doing, they The author acknowledges helpful comments from Huberto Ennis, Motoo Haruta, Gary Richardson, Robert Sharp, Kurt Schuler, Ellis Tallman, and Alexander Wolman. -

Farm Bill Workshop & GOVERNMENT Affairs Meeting

NATIONAL COUNCIL OF FARMER COOPERATIVES 2 0 WASHINGTON 1 7 CONFERENCE JUNE 26-28, 2017 HYATT REGENCY WASHINGTON, DC Farm Bill Workshop & GOVERNMENT aFFAIRS mEETING Farm Bill Workshop: Agenda NCFC Washington Conference Farm Bill Workshop Hyatt Regency Hotel Washington, DC June 26, 2017 AGENDA Columbia A/B Room 7:30 AM Registration Open & Breakfast Served 8:00 AM Welcome & Introductions 8:05 AM Balancing Priorities Against a Challenging Baseline Guest Speaker: Jonathan Coppess Clinical Assistant Professor University of Illinois 8:50 AM Crop Insurance & Risk Management Guest Speaker: Tara Smith Torrey & Associates 9:20 AM Priorities for Commodities, Specialty Crops & Livestock Guest Panelist: Sam Willett National Corn Growers Association Reece Langley National Cotton Council Ben Mosely USA Rice Federation John Hollay National Milk Producers Federation Robert Guenther United Fresh Produce Association Bill Davis National Pork Producers Association Representing the Business Interests of Agriculture 10:45 AM Break 11:00 AM Nutrition – Not a slush fund! Guest Speaker: Julian Baer Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition & Forestry U.S. Senate 11:30 AM Conservation, Energy & Research – Areas for Refocus Guest Panelists: Jason Weller Land O’Lakes, Inc. Former Chief, Natural Resources Conservation Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture Bobby Frederick National Grain & Feed Association Josh Maxwell Committee on Agriculture U.S. House of Representatives John Goldberg Science Based Strategies 12:30 PM Lunch 1:00 PM Trade, Rural Development & Credit – Opportunities -

Entity Classification: the One Hundred-Year Debate

Catholic University Law Review Volume 44 Issue 2 Winter 1995 Article 3 1995 Entity Classification: The One Hundred-Year Debate Patrick E. Hobbs Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Patrick E. Hobbs, Entity Classification: The One Hundred-Year Debate, 44 Cath. U. L. Rev. 437 (1995). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol44/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENTITY CLASSIFICATION: THE ONE HUNDRED-YEAR DEBATE Patrick E. Hobbs* I. Introduction ................................................. 437 II. Evolution of the Tax Definition of the Term "Corporation".. 441 A. The Revenue Act of 1894 ............................... 441 B. The Corporate Excise Tax of 1909 ....................... 452 C. After the Sixteenth Amendment: A Case of Floating Commas and Misplaced Modifiers ....................... 459 D. Developing a Corporate Composite ..................... 468 III. The Failure of the Resemblance Test ........................ 481 A. The Professional Corporation ............................ 481 B. The Limited Partnership ................................. 491 C. The Limited Liability Company .......................... 510 IV . Conclusion .................................................. 518 I. INTRODUCTION One hundred years ago, in the Revenue Act of 1894,1 Congress en- acted our Nation's first peacetime income tax.2 Although the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional within a year of its enactment,3 at least * Associate Professor of Law, Seton Hall University School of Law. B.S., 1982, Se- ton Hall University; J.D., 1985, University of North Carolina; LL.M., 1988, New York Uni- versity. -

FDIC Banking Review, Vol. 17, No. 4

Banking Review 2005 VOLUME 17, NO. 4 The U.S. Federal Financial Regulatory System: Restructuring Federal Bank Regulation (page 1) by Rose Marie Kushmeider Most observers of the U.S. financial regulatory system would agree that if it did not exist, no one would invent it. Most, however, would also admit that the system–despite all its faults–has served both the financial services industry and consumers well. This paper looks at arguments for and against reform in the context of changes taking place within the industry and around the world in other financial regulatory systems. Consolidation in the U.S. Banking Industry: Is the “Long, Strange Trip” About to End? (page 31) by Kenneth D. Jones and Tim Critchfield Consolidation has been an enduring trend in the U.S. banking industry for more than two decades. This article provides an overview of the structural changes that have occurred and explores the empirical research to determine how consolidtion has affected such things as asset concentration, competition, banking efficiency and profitability, shareholder value, and the availability and pricing of banking services. Finally, the authors speculate on how the current forces of change might affect the industy’s structure going forward. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Articles may be reprinted or abstracted if the FDIC Banking Review and author(s) are credited. Please provide the FDIC’s Division of Insurance and Research with a copy of any publications containing reprinted material. Acting Chairman Martin J. Gruenberg Director, Division of Insurance Arthur J. -

Populism, Economic Policies and Central Banking

Populism, Economic Policies and Central Banking Edited by Ernest Gnan and Donato Masciandaro Contributions by Itai Agur • Carola Binder • Cristina Bodea • Claudio Borio • Italo Colantone • Federico Favaretto • Ana Carolina Garriga • Stefan Gerlach • Ernest Gnan 0DVDDNL +LJDVKLMLPD 5\V]DUG .RNRV]F]\ĔVNL -RDQQD 0DFNLHZLF]à\]LDN 1LFROiV (UQHVWR Magud • Donato Masciandaro • Luljeta Minxhozi • Massimo Morelli • Francesco Passarelli • Antonio Spilimbergo • Piero Stanig • Alejandro M. Werner A joint publication with the Bocconi University DQG%$)),&$5(),1 Supported by SUERF – Société SUERF Universitaire Européenne Conference Proceedings de Recherches Financières 2020/1 Populism, Economic Policies and Central Banking POPULISM, ECONOMIC POLICIES AND CENTRAL BANKING Edited by Ernest Gnan and Donato Masciandaro Contributions by Itai Agur, Carola Binder, Cristina Bodea, Claudio Borio, Italo Colantone, Federico Favaretto, Ana Carolina Garriga, Stefan Gerlach, Ernest Gnan, Masaaki Higashijima, Ryszard Kokoszczyński, Joanna Mackiewicz-Łyziak, Nicolás Ernesto Magud, Donato Masciandaro, Luljeta Minxhozi, Massimo Morelli, Francesco Passarelli, Antonio Spilimbergo, Piero Stanig, Alejandro M. Werner A joint publication with the Bocconi University and BAFFI CAREFIN Supported by SUERF – The European Money and Finance Forum Vienna 2020 SUERF Conference Proceedings 2020/1 CIP Populism, Economic Policies and Central Banking Editors: Ernest Gnan and Donato Masciandaro Authors: Itai Agur, Carola Binder, Cristina Bodea, Claudio Borio, Italo Colantone, Ana Carolina Garriga, Stefan Gerlach, Ernest Gnan, Federico Favaretto, Masaaki Higashijima, Ryszard Kokoszczyński, Joanna Mackiewicz-Łyziak, Nicolás Ernesto Magud, Donato Masciandaro, Luljeta Minxhozi, Massimo Morelli, Francesco Passarelli, Antonio Spilimbergo, Piero Stanig, Alejandro M. Werner Keywords: Behavioural economics, Banking policy, Populism, Economic Policy, Central bank Independence, Financial Inequality, Political Economics, Political Economy, Fiscal policy, Populism, Latin America, Institutions. -

Tax Transparency and the Marketplace: a Pathway to State Sustainability

110474 001-130 int NB_43_corr_Ok-Proofs_PG 1_2015-01-09_11:24:08_K Tax Transparency and the Marketplace: A Pathway to State Sustainability Montano Cabezas* This article advances the argument that market to society. It then investigates how more diffuse participants, increasingly concerned about the measurements based on externality assessment 2014 CanLIIDocs 108 sustainability of the social benefits and oppor- could be used to “score” a company’s contribu- tunities derived from the state, are interested tion to society, and how such scoring could affect in how companies contribute to society via both the markets and tax policy. The article con- taxation. The article advocates that companies cludes by reiterating aspirations for tax transpar- should disclose their tax returns for each juris- ency, and by advocating for a new state-business diction in which they operate, in order to give tax paradigm in order to ensure the continued market participants a tool to better understand a viability of the state as a provider of social goods. company’s comprehensive economic contribution L’auteur avance que les acteurs économiques, façon dont la diffusion de mesures tenant de plus en plus préoccupés par la durabilité des compte des externalités peut aider les entreprises opportunités et des avantages sociaux fournis par à évaluer leur contribution sociétale ainsi que l’État, s’intéressent à la façon dont les entreprises l’impact d’une telle diffusion sur les marchés contribuent financièrement à la société grâce et sur la politique fiscale. L’auteur conclut en à l’impôt. L’auteur suggère que les entreprises réitérant ses aspirations pour des politiques devraient divulguer leurs déclarations de fiscales transparentes et en plaidant en faveur revenus dans chacune des juridictions où d’un nouveau paradigme fiscal entre l’État et elles opèrent afin de permettre aux acteurs les entreprises qui vise à assurer la viabilité de économiques de comprendre leur contribution l’État en tant que fournisseur de services sociaux.