Early History[Edit]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Evolutionary Approach for Sorting Algorithms

ORIENTAL JOURNAL OF ISSN: 0974-6471 COMPUTER SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY December 2014, An International Open Free Access, Peer Reviewed Research Journal Vol. 7, No. (3): Published By: Oriental Scientific Publishing Co., India. Pgs. 369-376 www.computerscijournal.org Root to Fruit (2): An Evolutionary Approach for Sorting Algorithms PRAMOD KADAM AND Sachin KADAM BVDU, IMED, Pune, India. (Received: November 10, 2014; Accepted: December 20, 2014) ABstract This paper continues the earlier thought of evolutionary study of sorting problem and sorting algorithms (Root to Fruit (1): An Evolutionary Study of Sorting Problem) [1]and concluded with the chronological list of early pioneers of sorting problem or algorithms. Latter in the study graphical method has been used to present an evolution of sorting problem and sorting algorithm on the time line. Key words: Evolutionary study of sorting, History of sorting Early Sorting algorithms, list of inventors for sorting. IntroDUCTION name and their contribution may skipped from the study. Therefore readers have all the rights to In spite of plentiful literature and research extent this study with the valid proofs. Ultimately in sorting algorithmic domain there is mess our objective behind this research is very much found in documentation as far as credential clear, that to provide strength to the evolutionary concern2. Perhaps this problem found due to lack study of sorting algorithms and shift towards a good of coordination and unavailability of common knowledge base to preserve work of our forebear platform or knowledge base in the same domain. for upcoming generation. Otherwise coming Evolutionary study of sorting algorithm or sorting generation could receive hardly information about problem is foundation of futuristic knowledge sorting problems and syllabi may restrict with some base for sorting problem domain1. -

History of Computer Science from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

History of computer science From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The history of computer science began long before the modern discipline of computer science that emerged in the 20th century, and hinted at in the centuries prior. The progression, from mechanical inventions and mathematical theories towards the modern concepts and machines, formed a major academic field and the basis of a massive worldwide industry.[1] Contents 1 Early history 1.1 Binary logic 1.2 Birth of computer 2 Emergence of a discipline 2.1 Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace 2.2 Alan Turing and the Turing Machine 2.3 Shannon and information theory 2.4 Wiener and cybernetics 2.5 John von Neumann and the von Neumann architecture 3 See also 4 Notes 5 Sources 6 Further reading 7 External links Early history The earliest known as tool for use in computation was the abacus, developed in period 2700–2300 BCE in Sumer . The Sumerians' abacus consisted of a table of successive columns which delimited the successive orders of magnitude of their sexagesimal number system.[2] Its original style of usage was by lines drawn in sand with pebbles . Abaci of a more modern design are still used as calculation tools today.[3] The Antikythera mechanism is believed to be the earliest known mechanical analog computer.[4] It was designed to calculate astronomical positions. It was discovered in 1901 in the Antikythera wreck off the Greek island of Antikythera, between Kythera and Crete, and has been dated to c. 100 BCE. Technological artifacts of similar complexity did not reappear until the 14th century, when mechanical astronomical clocks appeared in Europe.[5] Mechanical analog computing devices appeared a thousand years later in the medieval Islamic world. -

Alan Turingturing –– Computercomputer Designerdesigner

AlanAlan TuringTuring –– ComputerComputer DesignerDesigner Brian E. Carpenter with input from Robert W. Doran The University of Auckland May 2012 Turing, the theoretician ● Turing is widely regarded as a pure mathematician. After all, he was a B-star Wrangler (in the same year as Maurice Wilkes) ● “It is possible to invent a single machine which can be used to compute any computable sequence. If this machine U is supplied with the tape on the beginning of which is written the string of quintuples separated by semicolons of some computing machine M, then U will compute the same sequence as M.” (1937) ● So how was he able to write Proposals for development in the Mathematics Division of an Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) by the end of 1945? 2 Let’s read that carefully ● “It is possible to inventinvent a single machinemachine which can be used to compute any computable sequence. If this machinemachine U is supplied with the tapetape on the beginning of which is writtenwritten the string of quintuples separated by semicolons of some computing machinemachine M, then U will compute the same sequence as M.” ● The founding statement of computability theory was written in entirely physical terms. 3 What would it take? ● A tape on which you can write, read and erase symbols. ● Poulsen demonstrated magnetic wire recording in 1898. ● A way of storing symbols and performing simple logic. ● Eccles & Jordan patented the multivibrator trigger circuit (flip- flop) in 1919. ● Rossi invented the coincidence circuit (AND gate) in 1930. ● Building U in 1937 would have been only slightly more bizarre than building a differential analyser with Meccano. -

The History of Computing in the History of Technology

The History of Computing in the History of Technology Michael S. Mahoney Program in History of Science Princeton University, Princeton, NJ (Annals of the History of Computing 10(1988), 113-125) After surveying the current state of the literature in the history of computing, this paper discusses some of the major issues addressed by recent work in the history of technology. It suggests aspects of the development of computing which are pertinent to those issues and hence for which that recent work could provide models of historical analysis. As a new scientific technology with unique features, computing in turn can provide new perspectives on the history of technology. Introduction record-keeping by a new industry of data processing. As a primary vehicle of Since World War II 'information' has emerged communication over both space and t ime, it as a fundamental scientific and technological has come to form the core of modern concept applied to phenomena ranging from information technolo gy. What the black holes to DNA, from the organization of English-speaking world refers to as "computer cells to the processes of human thought, and science" is known to the rest of western from the management of corporations to the Europe as informatique (or Informatik or allocation of global resources. In addition to informatica). Much of the concern over reshaping established disciplines, it has information as a commodity and as a natural stimulated the formation of a panoply of new resource derives from the computer and from subjects and areas of inquiry concerned with computer-based communications technolo gy. -

Alan Turing's Automatic Computing Engine

5 Turing and the computer B. Jack Copeland and Diane Proudfoot The Turing machine In his first major publication, ‘On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem’ (1936), Turing introduced his abstract Turing machines.1 (Turing referred to these simply as ‘computing machines’— the American logician Alonzo Church dubbed them ‘Turing machines’.2) ‘On Computable Numbers’ pioneered the idea essential to the modern computer—the concept of controlling a computing machine’s operations by means of a program of coded instructions stored in the machine’s memory. This work had a profound influence on the development in the 1940s of the electronic stored-program digital computer—an influence often neglected or denied by historians of the computer. A Turing machine is an abstract conceptual model. It consists of a scanner and a limitless memory-tape. The tape is divided into squares, each of which may be blank or may bear a single symbol (‘0’or‘1’, for example, or some other symbol taken from a finite alphabet). The scanner moves back and forth through the memory, examining one square at a time (the ‘scanned square’). It reads the symbols on the tape and writes further symbols. The tape is both the memory and the vehicle for input and output. The tape may also contain a program of instructions. (Although the tape itself is limitless—Turing’s aim was to show that there are tasks that Turing machines cannot perform, even given unlimited working memory and unlimited time—any input inscribed on the tape must consist of a finite number of symbols.) A Turing machine has a small repertoire of basic operations: move left one square, move right one square, print, and change state. -

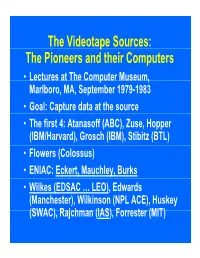

P the Pioneers and Their Computers

The Videotape Sources: The Pioneers and their Computers • Lectures at The Compp,uter Museum, Marlboro, MA, September 1979-1983 • Goal: Capture data at the source • The first 4: Atanasoff (ABC), Zuse, Hopper (IBM/Harvard), Grosch (IBM), Stibitz (BTL) • Flowers (Colossus) • ENIAC: Eckert, Mauchley, Burks • Wilkes (EDSAC … LEO), Edwards (Manchester), Wilkinson (NPL ACE), Huskey (SWAC), Rajchman (IAS), Forrester (MIT) What did it feel like then? • What were th e comput ers? • Why did their inventors build them? • What materials (technology) did they build from? • What were their speed and memory size specs? • How did they work? • How were they used or programmed? • What were they used for? • What did each contribute to future computing? • What were the by-products? and alumni/ae? The “classic” five boxes of a stored ppgrogram dig ital comp uter Memory M Central Input Output Control I O CC Central Arithmetic CA How was programming done before programming languages and O/Ss? • ENIAC was programmed by routing control pulse cables f ormi ng th e “ program count er” • Clippinger and von Neumann made “function codes” for the tables of ENIAC • Kilburn at Manchester ran the first 17 word program • Wilkes, Wheeler, and Gill wrote the first book on programmiidbBbbIiSiing, reprinted by Babbage Institute Series • Parallel versus Serial • Pre-programming languages and operating systems • Big idea: compatibility for program investment – EDSAC was transferred to Leo – The IAS Computers built at Universities Time Line of First Computers Year 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 ••••• BTL ---------o o o o Zuse ----------------o Atanasoff ------------------o IBM ASCC,SSEC ------------o-----------o >CPC ENIAC ?--------------o EDVAC s------------------o UNIVAC I IAS --?s------------o Colossus -------?---?----o Manchester ?--------o ?>Ferranti EDSAC ?-----------o ?>Leo ACE ?--------------o ?>DEUCE Whirl wi nd SEAC & SWAC ENIAC Project Time Line & Descendants IBM 701, Philco S2000, ERA.. -

Gsoc 2018 Project Proposal

GSoC 2018 Project Proposal Description: Implement the project idea sorting algorithms benchmark and implementation (2018) Applicant Information: Name: Kefan Yang Country of Residence: Canada University: Simon Fraser University Year of Study: Third year Major: Computing Science Self Introduction: I am Kefan Yang, a third-year computing science student from Simon Fraser University, Canada. I have rich experience as a full-stack web developer, so I am familiar with different kinds of database, such as PostgreSQL, MySQL and MongoDB. I have a much better understand of database system other than how to use it. In the database course I took in the university, I implemented a simple SQL database. It supports basic SQL statements like select, insert, delete and update, and uses a B+ tree to index the records by default. The size of each node in the B+ tree is set the disk block size to maximize performance of disk operation. Also, 1 several kinds of merging algorithms are used to perform a cross table query. More details about this database project can be found here. Additionally, I have very solid foundation of basic algorithms and data structure. I’ve participated in division 1 contest of 2017 ACM-ICPC Pacific Northwest Regionals as a representative of Simon Fraser University, which clearly shows my talents in understanding and applying different kinds of algorithms. I believe the contest experience will be a big help for this project. Benefits to the PostgreSQL Community: Sorting routine is an important part of many modules in PostgreSQL. Currently, PostgreSQL is using median-of-three quicksort introduced by Bentley and Mcllroy in 1993 [1], which is somewhat outdated. -

Software Studies: a Lexicon, Edited by Matthew Fuller, 2008

fuller_jkt.qxd 4/11/08 7:13 AM Page 1 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• S •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••new media/cultural studies ••••software studies •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• O ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• F software studies\ a lexicon ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• T edited by matthew fuller Matthew Fuller is David Gee Reader in ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• This collection of short expository, critical, Digital Media at the Centre for Cultural ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• W and speculative texts offers a field guide Studies, Goldsmiths College, University of to the cultural, political, social, and aes- London. He is the author of Media ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• thetic impact of software. Computing and Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and A digital media are essential to the way we Technoculture (MIT Press, 2005) and ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• work and live, and much has been said Behind the Blip: Essays on the Culture of ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• -

John W. Mauchly Papers Ms

John W. Mauchly papers Ms. Coll. 925 Finding aid prepared by Holly Mengel. Last updated on April 27, 2020. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2015 September 9 John W. Mauchly papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 8 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................8 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 10 Series I. Youth, education, and early career......................................................................................... 10 Series II. Moore School of Electrical Engineering, University of Pennsylvania................................. -

Alan Turing 1 Alan Turing

Alan Turing 1 Alan Turing Alan Turing Turing at the time of his election to Fellowship of the Royal Society. Born Alan Mathison Turing 23 June 1912 Maida Vale, London, England, United Kingdom Died 7 June 1954 (aged 41) Wilmslow, Cheshire, England, United Kingdom Residence United Kingdom Nationality British Fields Mathematics, Cryptanalysis, Computer science Institutions University of Cambridge Government Code and Cypher School National Physical Laboratory University of Manchester Alma mater King's College, Cambridge Princeton University Doctoral advisor Alonzo Church Doctoral students Robin Gandy Known for Halting problem Turing machine Cryptanalysis of the Enigma Automatic Computing Engine Turing Award Turing test Turing patterns Notable awards Officer of the Order of the British Empire Fellow of the Royal Society Alan Mathison Turing, OBE, FRS ( /ˈtjʊərɪŋ/ TEWR-ing; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954), was a British mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst, and computer scientist. He was highly influential in the development of computer science, giving a formalisation of the concepts of "algorithm" and "computation" with the Turing machine, which can be considered a model of a general purpose computer.[1][2][3] Turing is widely considered to be the father of computer science and artificial intelligence.[4] During World War II, Turing worked for the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park, Britain's codebreaking centre. For a time he was head of Hut 8, the section responsible for German naval cryptanalysis. He devised a number of techniques for breaking German ciphers, including the method of the bombe, an electromechanical machine that could find settings for the Enigma machine. -

Alan Turing's Other Universal Machine

viewpoints VDOI:10.1145/2209249.2209277 Martin Campbell-Kelly Historical Reflections Alan Turing’s Other Universal Machine Reflections on the Turing ACE computer and its influence. LL COMPUTER SCIENTISTS know about the Univer- sal Turing Machine, the theoretical construct the British genius Alan Turing Adescribed in his famous 1936 paper on the Entscheidungsproblem (the halting problem). The Turing Machine is one of the foundation stones of theoreti- cal computer science. Much less well known is the practical stored program computer he proposed after the war in February 1946. The computer was called the ACE—Automatic Comput- ing Engine—a name intended to evoke the spirit of Charles Babbage, the pio- neer of computing machines in the previous century. Almost all post-war electronic com- puters were, and still are, based on the famous EDVAC Report written by John von Neumann in June 1945 on behalf The Pilot ACE, May 1950. Jim Wilkinson (center right) and Donald Davies (right). of the computer group at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering at the roles. Computers were in the air and of one, and over the next few months University of Pennsylvania. Von Neu- universities at Manchester, Cam- he evolved the design of the ACE. His mann was very familiar with Turing’s bridge, and elsewhere established report was formally presented to the 1936 Entscheidungsproblem paper. In electronic computer projects. Out- NPL’s executive committee in Febru- 1937, Turing was a research assistant side the academic sphere, in Lon- ary 1946. at the Institute for Advanced Study at don, the National Physical Laboratory Although the ACE drew heavily on Princeton University, where von Neu- (NPL—Britain’s equivalent of the Na- the EDVAC Report, it had many novel mann was a professor of mathematics. -

David Link There Must Be an Angel on the Beginnings of the Arithmetics Of

david link There Must Be an Angel On the Beginnings of the Arithmetics of Rays From August 1953 to May 1954 strange love-letters appeared on the notice board of Manchester University’s Computer Department:1 “darling sweetheart you are my avid fellow feeling. my affection curiously clings to your passionate wish. my liking yearns for your heart. you are my wistful sympathy: my tender liking. yours beautifully m.u.c.”2 The acronym “M.U.C.” stood for “Manchester University Computer”, the ear- liest electronic, programmable, and universal calculating machine; the fully functional prototype was completed in June 1948.3 One of the very first software developers, Christopher Strachey (1916–1975), had used the built-in random generator of the Ferranti Mark I, the first industrially produced computer of this kind, to generate texts that are intended to express and arouse emotions. The 1 T. William Olle, personal communication, 21 February 2006: “I do remember a copy of the Strachey love-letter being put on the notice board and that must have been after August 1953 and probably prior to May 1954 (the date of Alan Turing’s death).” 2 Christopher Strachey, The “thinking” machine. Encounter. Literature, Arts, Politics 13 (1954): 25–31, p. 26. 3 Frederic C. Williams and Tom Kilburn, Electronic digital computers. Nature 162 (1948): 487. By “computing” and “calculating” I mean here and in the following in general the processing of data. Var- ious machines are claimed to be the “first” computer, but all others lack one of the properties men- tioned. The “ABC”, developed by John V.