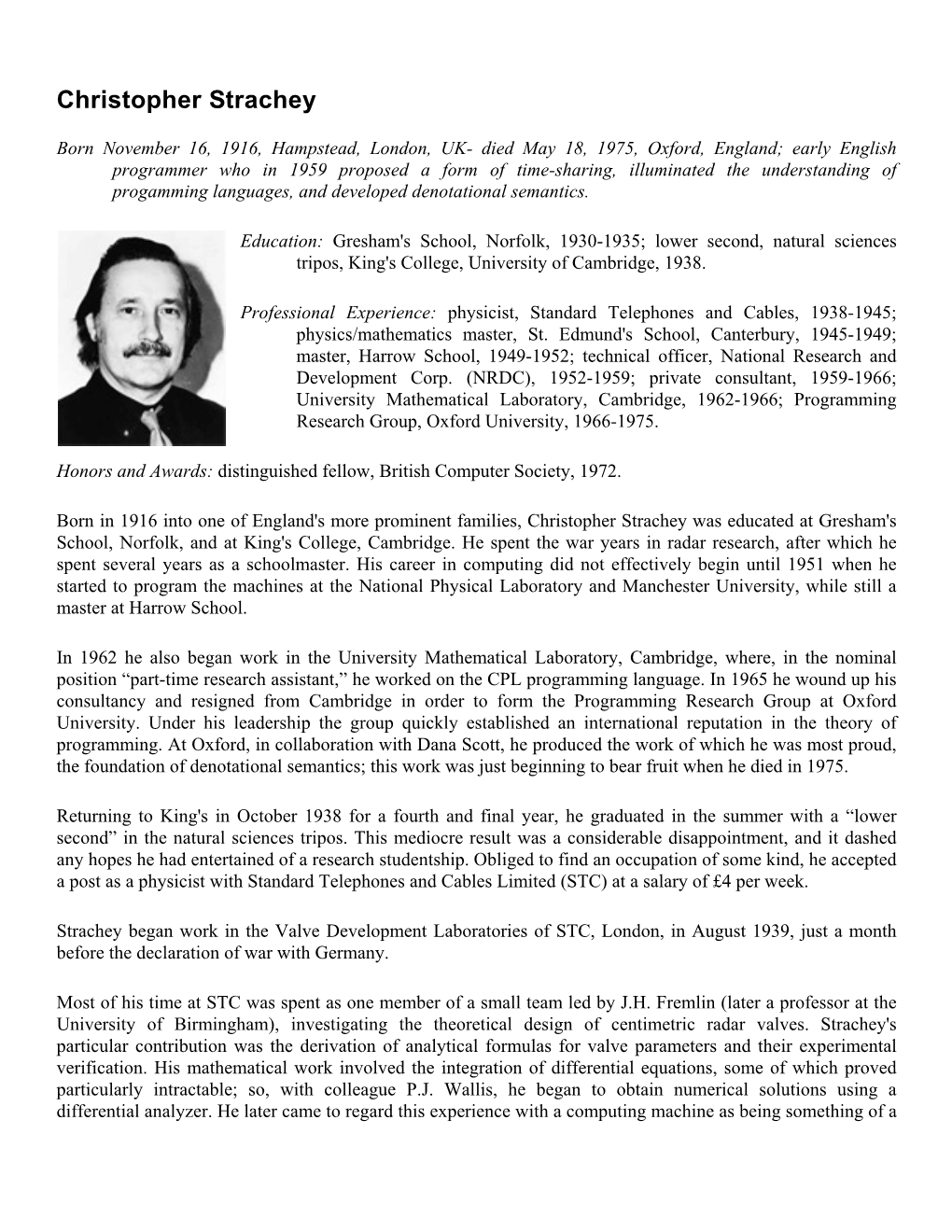

Christopher Strachey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Computer Science from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

History of computer science From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The history of computer science began long before the modern discipline of computer science that emerged in the 20th century, and hinted at in the centuries prior. The progression, from mechanical inventions and mathematical theories towards the modern concepts and machines, formed a major academic field and the basis of a massive worldwide industry.[1] Contents 1 Early history 1.1 Binary logic 1.2 Birth of computer 2 Emergence of a discipline 2.1 Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace 2.2 Alan Turing and the Turing Machine 2.3 Shannon and information theory 2.4 Wiener and cybernetics 2.5 John von Neumann and the von Neumann architecture 3 See also 4 Notes 5 Sources 6 Further reading 7 External links Early history The earliest known as tool for use in computation was the abacus, developed in period 2700–2300 BCE in Sumer . The Sumerians' abacus consisted of a table of successive columns which delimited the successive orders of magnitude of their sexagesimal number system.[2] Its original style of usage was by lines drawn in sand with pebbles . Abaci of a more modern design are still used as calculation tools today.[3] The Antikythera mechanism is believed to be the earliest known mechanical analog computer.[4] It was designed to calculate astronomical positions. It was discovered in 1901 in the Antikythera wreck off the Greek island of Antikythera, between Kythera and Crete, and has been dated to c. 100 BCE. Technological artifacts of similar complexity did not reappear until the 14th century, when mechanical astronomical clocks appeared in Europe.[5] Mechanical analog computing devices appeared a thousand years later in the medieval Islamic world. -

Part I Background

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19746-5 - Transitions and Trees: An Introduction to Structural Operational Semantics Hans Huttel Excerpt More information PART I BACKGROUND © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19746-5 - Transitions and Trees: An Introduction to Structural Operational Semantics Hans Huttel Excerpt More information 1 A question of semantics The goal of this chapter is to give the reader a glimpse of the applications and problem areas that have motivated and to this day continue to inspire research in the important area of computer science known as programming language semantics. 1.1 Semantics is the study of meaning Programming language semantics is the study of mathematical models of and methods for describing and reasoning about the behaviour of programs. The word semantics has Greek roots1 and was first used in linguistics. Here, one distinguishes among syntax, the study of the structure of lan- guages, semantics, the study of meaning, and pragmatics, the study of the use of language. In computer science we make a similar distinction between syntax and se- mantics. The languages that we are interested in are programming languages in a very general sense. The ‘meaning’ of a program is its behaviour, and for this reason programming language semantics is the part of programming language theory devoted to the study of program behaviour. Programming language semantics is concerned only with purely internal aspects of program behaviour, namely what happens within a running pro- gram. Program semantics does not claim to be able to address other aspects of program behaviour – e.g. -

Computer Conservation Society

Computer Conservation Society Aims and objectives The Computer Conservation Society (CCS) is a co-operative venture between the British Computer Society, the Science Museum of London and the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester. The CCS was constituted in September 1989 as a Specialist Group of the British Computer Society (BCS). It is thus covered by the Royal Charter and charitable status of the BCS. The aims of the CCS are to Promote the conservation of historic computers and to identify existing computers which may need to be archived in the future Develop awareness of the importance of historic computers Encourage research on historic computers and their impact on society Membership is open to anyone interested in computer conservation and the history of computing. The CCS is funded and supported by voluntary subscriptions from members, a grant from the BCS, fees from corporate membership, do- nations, and by the free use of Science Museum facilities. Some charges may be made for publications and attendance at seminars and conferences. There are a number of active Working Parties on specific computer restorations and early computer technologies and software. Younger peo- ple are especially encouraged to take part in order to achieve skills transfer. Resurrection The Bulletin of the Computer Conservation Society ISSN 0958 - 7403 Number 30 Spring 2003 Contents Generous BCS Support for Bombe Rebuild Project Ernest Morris, Chairman 2 AGM 2 News Round-Up 3 Society Activity 6 CCS Collection Policy 11 DAP snippets Brian M Russell 12 CCS Web Site Information 12 British Computer Corporation | a 1956 Venture Hugh McGregor Ross 13 Edsger Dijkstra remembered Brian Shearing 22 Deciphering Ancient Floppy Discs Kevin Murrell 26 The ICL Archive Hamish Carmichael 28 Forthcoming Events 31 Generous BCS Support for Bombe Rebuild Project Ernest Morris, Chairman CCS members will be familiar with the good progress of the Bombe re- build from the regular reports in Resurrection by John Harper, the project manager. -

The Standard Model for Programming Languages: the Birth of A

The Standard Model for Programming Languages: The Birth of a Mathematical Theory of Computation Simone Martini Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Bologna, Italy INRIA, Sophia-Antipolis, Valbonne, France http://www.cs.unibo.it/~martini [email protected] Abstract Despite the insight of some of the pioneers (Turing, von Neumann, Curry, Böhm), programming the early computers was a matter of fiddling with small architecture-dependent details. Only in the sixties some form of “mathematical program development” will be in the agenda of some of the most influential players of that time. A “Mathematical Theory of Computation” is the name chosen by John McCarthy for his approach, which uses a class of recursively computable functions as an (extensional) model of a class of programs. It is the beginning of that grand endeavour to present programming as a mathematical activity, and reasoning on programs as a form of mathematical logic. An important part of this process is the standard model of programming languages – the informal assumption that the meaning of programs should be understood on an abstract machine with unbounded resources, and with true arithmetic. We present some crucial moments of this story, concluding with the emergence, in the seventies, of the need of more “intensional” semantics, like the sequential algorithms on concrete data structures. The paper is a small step of a larger project – reflecting and tracing the interaction between mathematical logic and programming (languages), identifying some -

The London University Atlas

The London University Atlas: A talk given at the Atlas 50th Anniversary Symposium on 5th December 2012. Dik Leatherdale. London >> Manchester London University was, indeed still is, a HUGE organisation even by the standards of this place. It’s a collegiate university the individual colleges spread across the capital from Queen Mary College in the east end to the baroque splendour of Royal Holloway in leafy Egham built, you may be interested to learn, upon the proceeds of Victorian patent medicines hardly any of which had any beneficial effect whatsoever. In the “build it yourself” era, two of the colleges took the plunge. At Imperial College, Keith Tocher, Sid Michaelson and Tony Brooker constructed the “Imperial College Computing Engine” using relays. With the benefit of hindsight, this looks like a dead end in development. But Imperial weren’t the only team to put their faith in relay technology. Neither were they the last. Yet amazingly, the legacy of ICCE lived on because of a chance lunchtime conversation years later between Tom Kilburn and Tony Brooker, the Atlas adder logical design was derived from that of ICCE. Over in the unlikely surroundings of Birkbeck College, Andrew Booth was building a series of low cost, low performance machines. His ambition was to build computers cheap enough for every college to be able to afford one. You might say he invented the minicomputer a decade before anybody noticed. His designs were taken up by the British Tabulating Machine company and became the ICT 1200 series; for a while the most popular computer in the UK. -

Alan Turingturing –– Computercomputer Designerdesigner

AlanAlan TuringTuring –– ComputerComputer DesignerDesigner Brian E. Carpenter with input from Robert W. Doran The University of Auckland May 2012 Turing, the theoretician ● Turing is widely regarded as a pure mathematician. After all, he was a B-star Wrangler (in the same year as Maurice Wilkes) ● “It is possible to invent a single machine which can be used to compute any computable sequence. If this machine U is supplied with the tape on the beginning of which is written the string of quintuples separated by semicolons of some computing machine M, then U will compute the same sequence as M.” (1937) ● So how was he able to write Proposals for development in the Mathematics Division of an Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) by the end of 1945? 2 Let’s read that carefully ● “It is possible to inventinvent a single machinemachine which can be used to compute any computable sequence. If this machinemachine U is supplied with the tapetape on the beginning of which is writtenwritten the string of quintuples separated by semicolons of some computing machinemachine M, then U will compute the same sequence as M.” ● The founding statement of computability theory was written in entirely physical terms. 3 What would it take? ● A tape on which you can write, read and erase symbols. ● Poulsen demonstrated magnetic wire recording in 1898. ● A way of storing symbols and performing simple logic. ● Eccles & Jordan patented the multivibrator trigger circuit (flip- flop) in 1919. ● Rossi invented the coincidence circuit (AND gate) in 1930. ● Building U in 1937 would have been only slightly more bizarre than building a differential analyser with Meccano. -

Current Issue of FACS FACTS

Issue 2021-2 July 2021 FACS A C T S The Newsletter of the Formal Aspects of Computing Science (FACS) Specialist Group ISSN 0950-1231 FACS FACTS Issue 2021-2 July 2021 About FACS FACTS FACS FACTS (ISSN: 0950-1231) is the newsletter of the BCS Specialist Group on Formal Aspects of Computing Science (FACS). FACS FACTS is distributed in electronic form to all FACS members. Submissions to FACS FACTS are always welcome. Please visit the newsletter area of the BCS FACS website for further details at: https://www.bcs.org/membership/member-communities/facs-formal-aspects- of-computing-science-group/newsletters/ Back issues of FACS FACTS are available for download from: https://www.bcs.org/membership/member-communities/facs-formal-aspects- of-computing-science-group/newsletters/back-issues-of-facs-facts/ The FACS FACTS Team Newsletter Editors Tim Denvir [email protected] Brian Monahan [email protected] Editorial Team: Jonathan Bowen, John Cooke, Tim Denvir, Brian Monahan, Margaret West. Contributors to this issue: Jonathan Bowen, Andrew Johnstone, Keith Lines, Brian Monahan, John Tucker, Glynn Winskel BCS-FACS websites BCS: http://www.bcs-facs.org LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/2427579/ Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/pages/BCS-FACS/120243984688255 Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BCS-FACS If you have any questions about BCS-FACS, please send these to Jonathan Bowen at [email protected]. 2 FACS FACTS Issue 2021-2 July 2021 Editorial Dear readers, Welcome to the 2021-2 issue of the FACS FACTS Newsletter. A theme for this issue is suggested by the thought that it is just over 50 years since the birth of Domain Theory1. -

The Birth of a Mathematical Theory of Computation

The Standard Model for Programming Languages: The Birth of a Mathematical Theory of Computation Simone Martini Universit`adi Bologna and INRIA Sophia-Antipolis Bologna, 27 November 2020 Happy birthday, Maurizio! 1 / 58 This workshop: Recent Developments of the Design and Implementation of Programming Languages Well, not so recent: we go back exactly 60 years! It's more a revisionist's tale. 2 / 58 This workshop: Recent Developments of the Design and Implementation of Programming Languages Well, not so recent: we go back exactly 60 years! It's more a revisionist's tale. 3 / 58 viewpoints VDOI:10.1145/2542504 Thomas Haigh Historical Reflections HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF LOGIC, 2015 Actually, Turing Vol. 36, No. 3, 205–228, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01445340.2015.1082050 Did Not Invent Edgar G. Daylight the Computer Separating the origins of computer science and technology.Towards a Historical Notion of ‘Turing—the Father of Computer Science’ viewpoints HE 100TH ANNIVERSARY of the birth of Alan Turing was cel- EDGAR G. DAYLIGHT ebrated in 2012. The com- viewpointsputing community threw its Utrecht University, The Netherlands biggest ever birthday party. [email protected]:10.1145/2658985V TMajor events were organized around the world, including conferences or festi- vals in Princeton, Cambridge, Manches- Viewpoint Received 14 January 2015 Accepted 3 March 2015 ter, and Israel. There was a concert in Seattle and an opera in Finland. Dutch In the popular imagination, the relevance of Turing’s theoretical ideas to people producing actual machines was and French researchers built small Tur- Why Did Computer ing Machines out of Lego Mindstorms significant and appreciated by everybody involved in computing from the moment he published his 1936 paper kits. -

Alan Turing's Automatic Computing Engine

5 Turing and the computer B. Jack Copeland and Diane Proudfoot The Turing machine In his first major publication, ‘On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem’ (1936), Turing introduced his abstract Turing machines.1 (Turing referred to these simply as ‘computing machines’— the American logician Alonzo Church dubbed them ‘Turing machines’.2) ‘On Computable Numbers’ pioneered the idea essential to the modern computer—the concept of controlling a computing machine’s operations by means of a program of coded instructions stored in the machine’s memory. This work had a profound influence on the development in the 1940s of the electronic stored-program digital computer—an influence often neglected or denied by historians of the computer. A Turing machine is an abstract conceptual model. It consists of a scanner and a limitless memory-tape. The tape is divided into squares, each of which may be blank or may bear a single symbol (‘0’or‘1’, for example, or some other symbol taken from a finite alphabet). The scanner moves back and forth through the memory, examining one square at a time (the ‘scanned square’). It reads the symbols on the tape and writes further symbols. The tape is both the memory and the vehicle for input and output. The tape may also contain a program of instructions. (Although the tape itself is limitless—Turing’s aim was to show that there are tasks that Turing machines cannot perform, even given unlimited working memory and unlimited time—any input inscribed on the tape must consist of a finite number of symbols.) A Turing machine has a small repertoire of basic operations: move left one square, move right one square, print, and change state. -

The Discoveries of Continuations

LISP AND SYMBOLIC COMPUTATION: An InternationM JournM, 6, 233-248, 1993 @ 1993 Kluwer Academic Publishers - Manufactured in The Nett~eriands The Discoveries of Continuations JOHN C. REYNOLDS ( [email protected] ) School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213-3890 Keywords: Semantics, Continuation, Continuation-Passing Style Abstract. We give a brief account of the discoveries of continuations and related con- cepts by A. van Vv'ijngaarden, A. W. Mazurkiewicz, F. L. Morris, C. P. Wadsworth. J. H. Morris, M. J. Fischer, and S. K. Abdali. In the early history of continuations, basic concepts were independently discovered an extraordinary number of times. This was due less to poor communication among computer scientists than to the rich variety of set- tings in which continuations were found useful: They underlie a method of program transformation (into continuation-passing style), a style of def- initionM interpreter (defining one language by an interpreter written in another language), and a style of denotational semantics (in the sense of Scott and Strachey). In each of these settings, by representing "the mean- ing of the rest of the program" as a function or procedure, continnations provide an elegant description of a variety of language constructs, including call by value and goto statements. 1. The Background In the early 1960%, the appearance of Algol 60 [32, 33] inspired a fi~rment of research on the implementation and formal definition of programming languages. Several aspects of this research were critical precursors of the discovery of continuations. The ability in Algol 60 to jump out of blocks, or even procedure bod- ies, forced implementors to realize that the representation of a label must include a reference to an environment. -

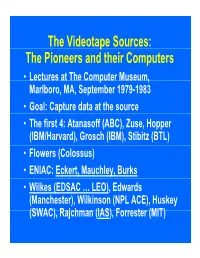

P the Pioneers and Their Computers

The Videotape Sources: The Pioneers and their Computers • Lectures at The Compp,uter Museum, Marlboro, MA, September 1979-1983 • Goal: Capture data at the source • The first 4: Atanasoff (ABC), Zuse, Hopper (IBM/Harvard), Grosch (IBM), Stibitz (BTL) • Flowers (Colossus) • ENIAC: Eckert, Mauchley, Burks • Wilkes (EDSAC … LEO), Edwards (Manchester), Wilkinson (NPL ACE), Huskey (SWAC), Rajchman (IAS), Forrester (MIT) What did it feel like then? • What were th e comput ers? • Why did their inventors build them? • What materials (technology) did they build from? • What were their speed and memory size specs? • How did they work? • How were they used or programmed? • What were they used for? • What did each contribute to future computing? • What were the by-products? and alumni/ae? The “classic” five boxes of a stored ppgrogram dig ital comp uter Memory M Central Input Output Control I O CC Central Arithmetic CA How was programming done before programming languages and O/Ss? • ENIAC was programmed by routing control pulse cables f ormi ng th e “ program count er” • Clippinger and von Neumann made “function codes” for the tables of ENIAC • Kilburn at Manchester ran the first 17 word program • Wilkes, Wheeler, and Gill wrote the first book on programmiidbBbbIiSiing, reprinted by Babbage Institute Series • Parallel versus Serial • Pre-programming languages and operating systems • Big idea: compatibility for program investment – EDSAC was transferred to Leo – The IAS Computers built at Universities Time Line of First Computers Year 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 ••••• BTL ---------o o o o Zuse ----------------o Atanasoff ------------------o IBM ASCC,SSEC ------------o-----------o >CPC ENIAC ?--------------o EDVAC s------------------o UNIVAC I IAS --?s------------o Colossus -------?---?----o Manchester ?--------o ?>Ferranti EDSAC ?-----------o ?>Leo ACE ?--------------o ?>DEUCE Whirl wi nd SEAC & SWAC ENIAC Project Time Line & Descendants IBM 701, Philco S2000, ERA.. -

Chiasmic Rhetoric: Alan Turing Between Bodies and Words Patricia Fancher Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 8-2014 Chiasmic Rhetoric: Alan Turing Between Bodies and Words Patricia Fancher Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Fancher, Patricia, "Chiasmic Rhetoric: Alan Turing Between Bodies and Words" (2014). All Dissertations. 1285. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1285 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHIASMIC RHETORIC: ALAN TURING BETWEEN BODIES AND WORDS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorate of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Patricia Fancher August 2014 Accepted by: Dr. Steven B. Katz, Committee Chair Dr. Diane Perpich Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. D. Travers Scott DISSERTATION ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzes the life and writing of inventor and scientist Alan Turing in order to define and theorize chiasmic relations between bodies and texts. Chiasmic rhetoric, as I develop throughout the dissertation, is the dynamic processes between materials and discourses that interact to construct powerful rhetorical effect, shape bodies, and also compose new knowledges. Throughout the dissertation, I develop chiasmic rhetoric as intersecting bodies and discourse, dynamic and productive, and potentially destabilizing. Turing is an unusual figure for research on bodily rhetoric and embodied knowledge. He is often associated with disembodied knowledge and as his inventions are said to move intelligence towards greater abstraction and away from human bodies.