Appendix E Lexico-Semantic Associations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Chapter 1 Introduction As a Chinese Buddhist in Malaysia, I Have Been

Chapter 1 Introduction As a Chinese Buddhist in Malaysia, I have been unconsciously entangled in a historical process of the making of modern Buddhism. There was a Chinese temple beside my house in Penang, Malaysia. The main deity was likely a deified imperial court officer, though no historical record documented his origin. A mosque serenely resided along the main street approximately 50 meters from my house. At the end of the street was a Hindu temple decorated with colorful statues. Less than five minutes’ walk from my house was a Buddhist association in a two-storey terrace. During my childhood, the Chinese temple was a playground. My friends and I respected the deities worshipped there but sometimes innocently stole sweets and fruits donated by worshippers as offerings. Each year, three major religious events were organized by the temple committee: the end of the first lunar month marked the spring celebration of a deity in the temple; the seventh lunar month was the Hungry Ghost Festival; and the eighth month honored, She Fu Da Ren, the temple deity’s birthday. The temple was busy throughout the year. Neighbors gathered there to chat about national politics and local gossip. The traditional Chinese temple was thus deeply rooted in the community. In terms of religious intimacy with different nearby temples, the Chinese temple ranked first, followed by the Hindu temple and finally, the mosque, which had a psychological distant demarcated by racial boundaries. I accompanied my mother several times to the Hindu temple. Once, I asked her why she prayed to a Hindu deity. -

A 1. Vbl. Par. 1St. Pers. Sg. Past & Present

A A 1. vbl. par. 1st. pers. sg. past & present - I - A peiki, I refuse, I won't, I can't. A ninayua kiweva vagagi. I am in two minds about a thing. A gisi waga si laya. I see the sails of the canoes. (The pronoun yaegu I, needs not to be expressed but for emphasis, being understood from the verbal particle.) 2. Abrev. of AMA. A-ma-tau-na? Which this man? 3. changes into E in dipthongues AI? EL? E. Paila, peila, pela. Wa valu- in village - We la valu - in his village. Ama toia, Ametoia, whence. Amenana, Which woman? Changes into I, sg. latu (son) pl. Litu -- vagi, to do, ku vigaki. Changes into O, i vitulaki - i vituloki wa- O . Changes into U, sg. tamala, father, - Pl. tumisia. sg. tabula gd.-father, pl. tubula. Ama what, amu, in amu ku toia? Where did you come from? N.B. several words beginning with A will be found among the KA 4. inverj. of disgust, disappointment. 5. Ambeisa wolaula? How Long? [see page 1, backside] ageva, or kageva small, fine shell disks. (beads in Motu) ago exclaims Alas! Agou! (pain, distress) agu Adj. poss. 1st. pers. sg. expressing near possession. See Grammar. Placed before the the thing possessed. Corresponds to gu, which is suffixed to the thing possessed. According to the classes of the nouns in Melanesian languages. See in the Grammar differences in Boyova. Memo: The other possess. are kagu for food, and ula for remove possession, both placed before the things possessed. Dabegu, my dress or dresses, - the ones I am wearing. -

BOOK of ABSTRACTS June 28 to July 2, 2021 15Th ICAL 2021 WELCOME

15TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON AUSTRONESIAN LINGUISTICS BOOK OF ABSTRACTS June 28 to July 2, 2021 15th ICAL 2021 WELCOME The Austronesian languages are a family of languages widely dispersed throughout the islands of The name Austronesian comes from Latin auster ICAL The 15-ICAL wan, Philippines 15th ICAL 2021 ORGANIZERS Department of Asian Studies Sinophone Borderlands CONTACTS: [email protected] [email protected] 15th ICAL 2021 PROGRAMME Monday, June 28 8:30–9:00 WELCOME 9:00–10:00 EARLY CAREER PLENARY | Victoria Chen et al | CHANNEL 1 Is Malayo-Polynesian a primary branch of Austronesian? A view from morphosyntax 10:00–10:30 COFFEE BREAK | CHANNEL 3 CHANNEL 1 CHANNEL 2 S2: S1: 10:30-11:00 Owen Edwards and Charles Grimes Yoshimi Miyake A preliminary description of Belitung Malay languages of eastern Indonesia and Timor-Leste Atsuko Kanda Utsumi and Sri Budi Lestari 11:00-11:30 Luis Ximenes Santos Language Use and Language Attitude of Kemak dialects in Timor-Leste Ethnic groups in Indonesia 11:30-11:30 Yunus Sulistyono Kristina Gallego Linking oral history and historical linguistics: Reconstructing population dynamics, The case of Alorese in east Indonesia agentivity, and dominance: 150 years of language contact and change in Babuyan Claro, Philippines 12:00–12:30 COFFEE BREAK | CHANNEL 3 12:30–13:30 PLENARY | Olinda Lucas and Catharina Williams-van Klinken | CHANNEL 1 Modern poetry in Tetun Dili CHANNEL 1 CHANNEL -

SASC Archive June 21 2021

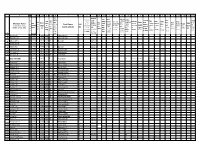

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z AA AB AC AD Cur Season Southpor Meb Primary Anv. Lord Other G Past Gold t/ Syd to Immed. Hon Lengt Last Boat Regt/ Howe Syd. Hob.- Director Vice Rear Hon. Chair e Joi Hon typ: Medal - Kelly Gold sources: Com Past Rac Hon h in Year Ann. Year Aust years Skip. (First & Comm Comm Racing Hon Member Name n n Life & HL LM Boat Name Sail Name Cup Island Coast 100bk, Comm. Sec. Capt. Joined in Year & Day (C=crew Last Year mod. (Years (Years Sec Tres FT or Non Memb. Racing d Rep Life LMA (First Name Win Visits Race 125bk, (Years (Years (Years in Start Yr (sail # added) No (Years in (Comm (Years (Years in Open (Version: June 21, 2021) SASC Ann. OM IM - use to Div. Reg. on yacht Anv on in in in office) e Yr Mem (Year) (C=Crew (C=crew enced in Office) ers in ? trace name (ex Jubilee shown) Office) in Office) boat r Rep. b. AM (div. on yacht on yacht Regat, Board) Office) office) Office) & Cent. in 1962) office) class ACM changes) win.) shown) shown) Trove 1 CRW Plate HB) 2 Franklin G M 2005 2009 2011 Shambles(2) 2 3 Franklin J M M 2005 2009 2011 Shambles(2) 2 1993 HT Sir M 1920 1954 2016 LM 7 4 Albert A F Norn(7) 1995 HT 5 Dietrich E M M 1878 1971 1896 7 1878-89 1883-89 1878-81 1993 HT Albert R O M 1997 1999 2020 OM 7 6 Norn(7) 1995 HT 7 Lorrimer L C M 1997 2012 2020 OM Barranoa(7) 7 2020-?? 2020-? 8 Lorrimer M M 2019 2012 2020 OM Barranoa(7) 7 9 Barclay F A M 1946 1954 2002 LM Sulaire(8) 8 1926-28 Gale E C (Cliff) M 1910 1921 HL Wendy(9) 9 1952 D2 HB 1925-50 1948-50 1938-46 1925-26 10 1947-48 11 -

Swahili-English Dictionary, the First New Lexical Work for English Speakers

S W AHILI-E N GLISH DICTIONARY Charles W. Rechenbach Assisted by Angelica Wanjinu Gesuga Leslie R. Leinone Harold M. Onyango Josiah Florence G. Kuipers Bureau of Special Research in Modern Languages The Catholic University of Americ a Prei Washington. B. C. 20017 1967 INTRODUCTION The compilers of this Swahili-English dictionary, the first new lexical work for English speakers in many years, hope that they are offering to students and translators a more reliable and certainly a more up-to-date working tool than any previously available. They trust that it will prove to be of value to libraries, researchers, scholars, and governmental and commercial agencies alike, whose in- terests and concerns will benefit from a better understanding and closer communication with peoples of Africa. The Swahili language (Kisuiahili) is a Bantu language spoken by perhaps as many as forty mil- lion people throughout a large part of East and Central Africa. It is, however, a native or 'first' lan- guage only in a nnitp restricted area consisting of the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba and the oppo- site coast, roughly from Dar es Salaam to Mombasa, Outside this relatively small territory, elsewhere in Kenya, in Tanzania (formerly Tanganyika), Copyright © 1968 and to a lesser degree in Uganda, in the Republic of the Congo, and in other fringe regions hard to delimit, Swahili is a lingua franca of long standing, a 'second' (or 'third' or 'fourth') language enjoy- ing a reasonably well accepted status as a supra-tribal or supra-regional medium of communication. THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA PRESS, INC. -

Papers in Pidgin and Creole Linguistics No. 5

Papers in pidgin and creole linguistics No.5 Mühlhäusler, P. editor. Papers in Pidgin and Creole Linguistics No. 5. A-91, v + 213 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1998. DOI:10.15144/PL-A91.cover ©1998 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurrn EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), Thomas E. Dutton, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at the Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financedlargely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. Publications in Series A, B and C and textbooks in Series D are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise who are normally not members of the editorial board. To date Pacific Linguistics has published over 400 volumes in four series: -Series A: Occasional Papers; collections of shorter papers, usually on a single topic or area. -

Bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages

Appendix B bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages Languages are constantly changing. As they grow and evolve, they can branch off or con- verge. Many languages are known by more than one name, or have alternate spellings. Some languages may be affected by political change. Even linguists differ in their defini- tions of language. While it is impossible to ascertain exactly how many languages exist on Earth, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., lists 6,809 living languages worldwide. The following list was adapted from The World Factbook 2002, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., and the Directory of Languages Spoken by Students of Limited English Proficiency in New York State Programs. What may seem like a language omission or oversight may be a difference in spelling or variation on the name. The list below may not be complete or all-inclusive; however, much effort went into making it as accurate as possible. Afghanistan Southern Pashto, Eastern Farsi, Uzbek, Turkmen, Brahui, Balochi, Hazaragi Albania Tosk Albanian, Gheg Albanian, Macedo-Romanian, Greek, Vlax Romani Algeria Arabic (official), French, Kabyle, Chaouia American Samoa Samoan, English Andorra Catalán (official), French, Spanish Angola Portuguese (official), Umbundu, Nyemba, Nyaneka, Loanda-Mbundu, Luchazi, Kongo, Chokwe Anguilla English (official), Anguillan Creole English Antigua and Barbuda English (official), Antigua Creole English, Barbuda Creole English Argentina Spanish (official), Pampa, English, Italian, German, French, Guaraní, Araucano, Quechua Armenia Armenian, Russian, North Azerbaijani -

World Languages Using Latin Script

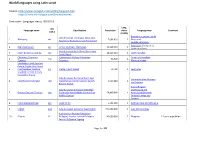

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

Clinton Independent, VOL

Clinton Independent, VOL. XXVII.—NO. 40. ST. JOHNS, MICH.. THURSDAY MORNING, JUNE 29. 1893. WHOLE NO -1393. Spectacles and Eye Glasses at almost — Wool. 16 to ‘JO cents. personal . Portland. She will attend the Ypsi K—yo e'a Near Feed Burn. \ wholesale prices at Krepps. DeWitt A —The most vivid Are scene ever at lanti Normal next year. —Portland Re Having purchased the old Anstey Celebration in St. Johns I Co.’s. Eyes tested free. tempted. at Newton Hall, July 3. Herman Goette spent Sunday in Pon view, House property. In St. Johns, have coo- time. vetted It into a commodious, conven The celebrated $1.00 Spectacles at —Born to Mr. and Mrs. C. E. Chapin, Geo. Muuro. who has beau sorely Mrs. U. V. Weedeu spent last Tues ient and safe Boarding aud Feed Barn, Allison’s. June 27, 1868, a son and heir. afflicted witli inflammatory rheumatism where the public may find clean food —The bcauti ful grounds of Mr. John day with friends In Ovid. during the last two weeks, was out yes for their animals and careful, compe HOME MATTERS. Hicks are being further ornamented by II. J. Patterson returned from the terday for the first time since the visita tent and gentlemanly attendants. A waiting room for ladies while their tbe addltiou of flagstone walks. World’s Fair last Monday. tion of his affliction. Riwv INm. Mias Pauline Adams, who has hones are being not in readiness, h —The boy Bence was convicted for Mrs. Mary Hogan, mother of Mrs. F. been provided. Prioes as low as the —“Uncle Jason. -

Monguor; Sketch Grammar of the Karlong Variety

SKETCH GRAMMAR OF THE KARLONG VARIETY OF MONGGHUL, AND DIALECTAL SURVEY OF MONGGHUL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS DECEMBER 2007 By Burgel R.M. Faehndrich Dissertation Committee: Alexander Vovin, Chairperson Robert Blust Kenneth Rehg David Stampe Virginia Bennett Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3302132 Copyright 2007 by Faehndrich, Burgel R.M. All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3302132 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. © 2007, Burgel R.M. Faehndrich iii Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The number of people who helped me in the course of my research, providing language information, translation, advice, and practical support is too great for me to list everyone individually. -

The Spirit of Minerva: Notes on a Border Dispute in the Pacific

The Spirit of Minerva: Notes on a Border Dispute in the Pacific Elisapeci Samanunu Waqanivala Abstract This paper examines the territorial dispute between Tonga and Fiji over Minerva Reef – an atoll located in the Pacific Ocean to the south of both countries. The dispute escalated in mid-2011 when Fiji destroyed navigational beacons erected by Tonga on the reef. This paper traces the history of the dispute and explores the positions of Tonga, Fiji and other parties on the question of who owns Minerva. The paper argues that in order to understand the dynamics of the dispute, it is vital to take into account the indigenous histories of both Tonga and Fiji. These must be considered alongside the rise of British influence in the Pacific in the late nineteenth century, various developments in the United States and, finally, the adoption of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea in the 1970s. All of these factors, the paper argues, contributed to shifts in indigenous understandings of ocean boundaries and affected the parties’ positions in the dispute. Introduction This paper examines the dispute over Minerva Reef between Tonga and Fiji. This border dispute escalated in mid-2011 when Fiji destroyed the navigational beacons erected by Tonga on Minerva Reef as a security and safety measure to aid mariners, ships and yachters sailing near the area. The 1887 Tonga Proclamation was revisited in 1972 by the King of Tonga when he took his royal entourage to Minerva Reef. At the ceremony, the King declared that Minerva Reef belonged to Tonga. The 2011 standoff between Tonga and Fiji was triggered when Roko Ului Mara (also known as Lieutenant Colonel Ratu Tevita Mara), a senior Fiji military officer, escaped sedition charges but was rescued by a Tongan vessel in Minerva Reef. -

Earlywatercraft – a Global Perspective of Invention and Development

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289239067 Proposal of the Global Initiative: EarlyWatercraft – A global perspective of invention and development Book · January 2016 CITATIONS READS 0 6,788 1 author: Miran Erič Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia 44 PUBLICATIONS 87 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Visual language View project Underwater documentation methodology View project All content following this page was uploaded by Miran Erič on 06 September 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. GLOBAL INITIATIVE: Early Watercraft – A global perspective of invention and development Proposal of the Initiative (Edited by: Ronald Bockius and Miran Eriˇcwith Ambassadors) Vrhnika, Slovenia 19th - 23rd of April 2015 GLOBAL INITIATIVE: Early Watercraft – A global perspective of invention and development Figure 1: Symbolic meaning of the official EWA logotype Idria lace represent water net and connecting of all nation around the world Inner green round drawing representing our planet Earth Outer red round drawing represent the oldest and most important human invention Early Watercraft Initiative is the short name of the global initiative ”Early Watercraft - a global perspective of invention and development” Red colour of the name is the symbolic meaning of the oldest clay red pigment iron oxide used by humankind Early Watercraft – A global perspective of invention