Документ Microsoft Word

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use of Classification Algorithms for the Ice Jams Forecasting Problem

E3S Web of Conferences 163, 02008 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202016302008 IV Vinogradov Conference Use of classification algorithms for the ice jams forecasting problem Natalia Semenova1*, Alexey Sazonov1,2, Inna Krylenko1,2,andNatalia Frolova1 1 Lomonosov Moscow State University, GSP-1, Leninskie Gory, 119991, Moscow, Russia 2 Water Problems Institute of the Russian Academy of Science, Gubkina st., 3, 119333, Moscow, Russia Abstract. In the research the prediction of occurrence of ice jam based on the K Nearest Neighbor method was considered by example of the city of Velikiy Ustyug, located at the confluence of the Sukhona and Yug Rivers. A forecast accuracy of 82% was achieved based on selected most significant hydrological and meteorological features. 1 Introduction Floods gain a lead among natural disasters both in terms of area of distribution and damage caused for Russia. Flooding can be caused by snow cover melting, a large amount of precipitation, the effects of surges, a breakthrough of a dam, etc. For northern rivers, including rivers of the European part of Russia, ice jams often cause floods. The goal of this research is developing a methodology for predicting the occurrence of ice jam based on the machine learning method. The place of confluence of the Sukhona and Yug Rivers, where the city of Velikiy Ustyug is located, was chosen as the object of study. The probability of the ice jams formation in this area is 43.5% according to statistics. Their occurrence leads to an increase of water level and flooding of residential and utility buildings. 2 Data and methods Over the past two decades, there has been a huge leap in the development of computer technology and machine learning, which has allowed the application of various machine learning algorithms to a large number of applied problems, including the prediction of flood characteristics. -

Doi 10.23859/2587-8344-2019-3-1-2 Удк 94 (470.12).083

RESEARCH http://en.hpchsu.ru DOI 10.23859/2587-8344-2019-3-1-2 УДК 94 (470.12).083 Коновалов Федор Яковлевич Кандидат исторических наук, доцент, Научно-издательский центр «Древности Севера» (Вологда, Россия) [email protected] Konovalov Fedor Candidate of Historical Sciences, Associate Professor, Scientific and Publishing Centre ‘Antiquities of the North’ (Vologda, Russia) [email protected] Секретная агентура провинциальных губернских жандармских управлений в начале XX в. (на материалах Вологодского губернского жандармского управления)*1 Secret Agency of the Provincial Gendarmerie at the Beginning of the 20th Century (on the Materials of the Vologda Provincial Gendarme Department) Аннотация. Эффективная деятельность политического сыска царской России в начале XX в. была невозможна без использования секретной агентуры как главного источника ин- формации о противниках режима. Это было осознано как на уровне руководства Департа- мента полиции, так и органов, ведущих розыскную работу на местах, – губернских жандарм- ских управлений (ГЖУ). В статье рассматривается деятельность Вологодского ГЖУ по соз- данию сети осведомителей в рядах революционных групп и ссыльных на территории губер- нии, оценивается количественный и качественный состав данной сети. Результатом данной работы стало почти полное пресечение всяких попыток активности в рядах противников ца- * 1Для цитирования: Коновалов Ф.Я. Секретная агентура провинциальных губернских жандармских управлений в начале XX в. (на материалах Вологодского губернского жан- дармского управления // Historia Provinciae – Журнал региональной истории. 2019. Т. 3. № 1. С. 86–145. DOI: 10.23859/2587-8344-2019-3-1-2 For citation: Konovalov, F. Secret Agency of the Provincial Gendarmerie at the Beginning of the 20th Century (on the Materials of the Vologda Provincial Gendarme Department). Historia Provinciae – The Journal of Regional History, vol. -

The Periglacial Climate and Environment in Northern Eurasia

ARTICLE IN PRESS Quaternary Science Reviews 23 (2004) 1333–1357 The periglacial climate andenvironment in northern Eurasia during the Last Glaciation Hans W. Hubbertena,*, Andrei Andreeva, Valery I. Astakhovb, Igor Demidovc, Julian A. Dowdeswelld, Mona Henriksene, Christian Hjortf, Michael Houmark-Nielseng, Martin Jakobssonh, Svetlana Kuzminai, Eiliv Larsenj, Juha Pekka Lunkkak, AstridLys a(j, Jan Mangerude, Per Moller. f, Matti Saarnistol, Lutz Schirrmeistera, Andrei V. Sherm, Christine Siegerta, Martin J. Siegertn, John Inge Svendseno a Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), Telegrafenberg A43, Potsdam D-14473, Germany b Geological Faculty, St. Petersburg University, Universitetskaya 7/9, St. Petersburg 199034, Russian Federation c Institute of Geology, Karelian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Pushkinskaya 11, Petrozavodsk 125610, Russian Federation d Scott Polar Research Institute and Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CBZ IER, UK e Department of Earth Science, University of Bergen, Allegt.! 41, Bergen N-5007, Norway f Quaternary Science, Department of Geology, Lund University, Geocenter II, Solvegatan. 12, Lund Sweden g Geological Institute, University of Copenhagen, Øster Voldgade 10, Copenhagen DK-1350, Denmark h Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, Chase Ocean Engineering Lab, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH 03824, USA i Paleontological Institute, RAS, Profsoyuznaya ul., 123, Moscow 117868, Russia j Geological Survey of Norway, PO Box 3006 Lade, Trondheim N-7002, Norway -

Nepcon CB Public Summary Report V1.4 Main Audit Sokol Timber

NEPCon Evaluation of “Sokol Timber Company” Joint-Stock Company Compliance with the SBP Framework: Public Summary Report Main (Initial) Audit www.sbp-cert.org Focusing on sustainable sourcing solutions Completed in accordance with the CB Public Summary Report Template Version 1.4 For further information on the SBP Framework and to view the full set of documentation see www.sbp-cert.org Document history Version 1.0: published 26 March 2015 Version 1.1: published 30 January 2018 Version 1.2: published 4 April 2018 Version 1.3: published 10 May 2018 Version 1.4: published 16 August 2018 © Copyright The Sustainable Biomass Program Limited 2018 NEPCon Evaluation of “Sokol Timber Company” Joint-Stock Company: Public Summary Report, Main (Initial) Audit Page ii Focusing on sustainable sourcing solutions Table of Contents 1 Overview 2 Scope of the evaluation and SBP certificate 3 Specific objective 4 SBP Standards utilised 4.1 SBP Standards utilised 4.2 SBP-endorsed Regional Risk Assessment 5 Description of Company, Supply Base and Forest Management 5.1 Description of Company 5.2 Description of Company’s Supply Base 5.3 Detailed description of Supply Base 5.4 Chain of Custody system 6 Evaluation process 6.1 Timing of evaluation activities 6.2 Description of evaluation activities 6.3 Process for consultation with stakeholders 7 Results 7.1 Main strengths and weaknesses 7.2 Rigour of Supply Base Evaluation 7.3 Compilation of data on Greenhouse Gas emissions 7.4 Competency of involved personnel 7.5 Stakeholder feedback 7.6 Preconditions 8 Review -

Atlas of High Conservation Value Areas, and Analysis of Gaps and Representativeness of the Protected Area Network in Northwest R

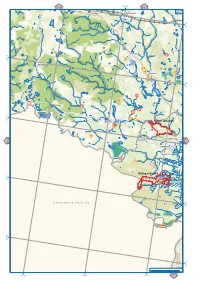

34°40' 216 217 Chudtsy Efimovsky 237 59°30' 59°20' Anisimovo Loshchinka River Somino Tushemelka River 59°20' Chagoda River Golovkovo Ostnitsy Spirovo 59°10' Klimovo Padun zakaznik Smordomsky 238 Puchkino 236 Ushakovo Ignashino Rattsa zakaznik 59°0' Rattsa River N O V G O R O D R E G I O N 59°0' 58°50' °50' 58 0369 км 34°20' 34°40' 35°0' 251 35°0' 35°20' 217 218 Glubotskoye Belaya Velga 238 protected mire protected mire Podgornoye Zaborye 59°30' Duplishche protected mire Smorodinka Volkhovo zakaznik protected mire Lid River °30' 59 Klopinino Mountain Stone protected mire (Kamennaya Gora) nature monument 59°20' BABAEVO Turgosh Vnina River °20' 59 Chadogoshchensky zakaznik Seredka 239 Pervomaisky 237 Planned nature monument Chagoda CHAGODA River and Pes River shores Gorkovvskoye protected mire Klavdinsky zakaznik SAZONOVO 59°10' Vnina Zalozno Staroye Ogarevo Chagodoshcha River Bortnikovo Kabozha Pustyn 59°0' Lake Chaikino nature monument Izbouishchi Zubovo Privorot Mishino °0' Pokrovskoye 59 Dolotskoye Kishkino Makhovo Novaya Planned nature monument Remenevo Kobozha / Anishino Chernoozersky Babushkino Malakhovskoye protected mire Kobozha River Shadrino Kotovo protected Chikusovo Kobozha mire zakazhik 58°50' Malakhovskoye / Kobozha 0369 protected mire км 35°20' 251 35°40' 36°0' 252 36°0' 36°20' 36°40' 218 219 239 Duplishche protected mire Kharinsky Lake Bolshoe-Volkovo zakaznik nature monument Planned nature monument Linden Alley 59°30' Pine forest Sudsky, °30' nature monument 59 Klyuchi zakaznik BABAEVO абаево Great Mosses Maza River 59°20' -

Interdisciplinary and Comparative Methodologies

The Retrospective Methods Network Newsletter Interdisciplinary and Comparative Methodologies № 14 Exploring Circum-Baltic Cultures and Beyond Guest Editors: Joonas Ahola and Kendra Willson Published by Folklore Studies / Department of Cultures University of Helsinki, Helsinki 1 RMN Newsletter is a medium of contact and communication for members of the Retrospective Methods Network (RMN). The RMN is an open network which can include anyone who wishes to share in its focus. It is united by an interest in the problems, approaches, strategies and limitations related to considering some aspect of culture in one period through evidence from another, later period. Such comparisons range from investigating historical relationships to the utility of analogical parallels, and from comparisons across centuries to developing working models for the more immediate traditions behind limited sources. RMN Newsletter sets out to provide a venue and emergent discourse space in which individual scholars can discuss and engage in vital cross- disciplinary dialogue, present reports and announcements of their own current activities, and where information about events, projects and institutions is made available. RMN Newsletter is edited by Frog, Helen F. Leslie-Jacobsen, Joseph S. Hopkins, Robert Guyker and Simon Nygaard, published by: Folklore Studies / Department of Cultures University of Helsinki PO Box 59 (Unioninkatu 38 C 217) 00014 University of Helsinki Finland The open-access electronic edition of this publication is available on-line at: https://www.helsinki.fi/en/networks/retrospective-methods-network Interdisciplinary and Comparative Methodologies: Exploring Circum-Baltic Cultures and Beyond is a special issue organized and edited by Frog, Joonas Ahola and Kendra Willson. © 2019 RMN Newsletter; authors retain rights to reproduce their own works and to grant permission for the reproductions of those works. -

Monuments of Church Architecture in Belozersk: Late Sixteenth to the Early Nineteenth Centuries

russian history 44 (2017) 260-297 brill.com/ruhi Monuments of Church Architecture in Belozersk: Late Sixteenth to the Early Nineteenth Centuries William Craft Brumfield Professor of Slavic Studies and Sizeler Professor of Jewish Studies, Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies, Tulane University, New Orleans [email protected] Abstract The history of the community associated with the White Lake (Beloe Ozero) is a rich one. This article covers a brief overview of the developing community from medieval through modern times, and then focuses the majority of its attention on the church ar- chitecture of Belozersk. This rich tradition of material culture increases our knowledge about medieval and early modern Rus’ and Russia. Keywords Beloozero – Belozersk – Russian Architecture – Church Architecture The origins and early location of Belozersk (now a regional town in the center of Vologda oblast’) are subject to discussion, but it is uncontestably one of the oldest recorded settlements among the eastern Slavs. “Beloozero” is mentioned in the Primary Chronicle (or Chronicle of Bygone Years; Povest’ vremennykh let) under the year 862 as one of the five towns granted to the Varangian brothers Riurik, Sineus and Truvor, invited (according to the chronicle) to rule over the eastern Slavs in what was then called Rus’.1 1 The Chronicle text in contemporary Russian translation is as follows: “B гoд 6370 (862). И изгнaли вapягoв зa мope, и нe дaли им дaни, и нaчaли caми coбoй влaдeть, и нe былo cpeди ниx пpaвды, и вcтaл poд нa poд, и былa у ниx уcoбицa, и cтaли вoeвaть дpуг c дpугoм. И cкaзaли: «Пoищeм caми ceбe князя, кoтopый бы влaдeл нaми и pядил пo pяду и пo зaкoну». -

Trends in Population Change and the Sustainable Socio-Economic Development of Cities in North-West Russia

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE BALTIC REGION TRENDS IN POPULATION CHANGE AND THE SUSTAINABLE SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF CITIES IN NORTH-WEST RUSSIA A. A. Anokhin K. D. Shelest M. A. Tikhonova Saint Petersburg State University Received 21 November 2018 7—9 Universitetskaya emb., Saint Petersburg, Russia, 199034 doi: 10.5922/2079-8555-2019-4-3 © Anokhin A. A., Shelest K. D., Tikhonova M. A., 2019 The Northwestern Federal District is a Russian macro-region that is a unique example of a model region. It accounts for 10 % of the country’s total area and 9.5 % of its population. This article aims to trace the patterns of city distribution across the region, to assess the conditions of differently populated cities and towns, and to identify sustainability trends in their socio-economic development. Population change is a reliable indicator of the competitiveness of a city. As a rule, a growing city performs well economically and has a favourable investment climate and high-paid jobs. The analysis revealed that population change occurred at different rates across the federal district in 2002—2017. A result of uneven socio-economic development, this irregularity became more serious as globalisation and open market advanced. The study links the causes and features of growth-related differences to the administrative status, location, and economic specialisation of northwestern cities. The migration behaviour of the population and the geoeconomic position are shown to be the main indicators of the sustainable development of a city. Keywords: cities, urban population, Northwestern Federal District, city classification, population, city sustainability Introduction When studying the urban population distribution and its dynamics over the past decades, it is necessary to take into account the territorial heterogeneity of To cite this article: Anokhin, A. -

Maps -- by Region Or Country -- Eastern Hemisphere -- Europe

G5702 EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5702 Alps see G6035+ .B3 Baltic Sea .B4 Baltic Shield .C3 Carpathian Mountains .C6 Coasts/Continental shelf .G4 Genoa, Gulf of .G7 Great Alföld .P9 Pyrenees .R5 Rhine River .S3 Scheldt River .T5 Tisza River 1971 G5722 WESTERN EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL G5722 FEATURES, ETC. .A7 Ardennes .A9 Autoroute E10 .F5 Flanders .G3 Gaul .M3 Meuse River 1972 G5741.S BRITISH ISLES. HISTORY G5741.S .S1 General .S2 To 1066 .S3 Medieval period, 1066-1485 .S33 Norman period, 1066-1154 .S35 Plantagenets, 1154-1399 .S37 15th century .S4 Modern period, 1485- .S45 16th century: Tudors, 1485-1603 .S5 17th century: Stuarts, 1603-1714 .S53 Commonwealth and protectorate, 1660-1688 .S54 18th century .S55 19th century .S6 20th century .S65 World War I .S7 World War II 1973 G5742 BRITISH ISLES. GREAT BRITAIN. REGIONS, G5742 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .C6 Continental shelf .I6 Irish Sea .N3 National Cycle Network 1974 G5752 ENGLAND. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5752 .A3 Aire River .A42 Akeman Street .A43 Alde River .A7 Arun River .A75 Ashby Canal .A77 Ashdown Forest .A83 Avon, River [Gloucestershire-Avon] .A85 Avon, River [Leicestershire-Gloucestershire] .A87 Axholme, Isle of .A9 Aylesbury, Vale of .B3 Barnstaple Bay .B35 Basingstoke Canal .B36 Bassenthwaite Lake .B38 Baugh Fell .B385 Beachy Head .B386 Belvoir, Vale of .B387 Bere, Forest of .B39 Berkeley, Vale of .B4 Berkshire Downs .B42 Beult, River .B43 Bignor Hill .B44 Birmingham and Fazeley Canal .B45 Black Country .B48 Black Hill .B49 Blackdown Hills .B493 Blackmoor [Moor] .B495 Blackmoor Vale .B5 Bleaklow Hill .B54 Blenheim Park .B6 Bodmin Moor .B64 Border Forest Park .B66 Bourne Valley .B68 Bowland, Forest of .B7 Breckland .B715 Bredon Hill .B717 Brendon Hills .B72 Bridgewater Canal .B723 Bridgwater Bay .B724 Bridlington Bay .B725 Bristol Channel .B73 Broads, The .B76 Brown Clee Hill .B8 Burnham Beeches .B84 Burntwick Island .C34 Cam, River .C37 Cannock Chase .C38 Canvey Island [Island] 1975 G5752 ENGLAND. -

Departure City City Of Delivery Region Delivery Delivery Time

Cost of Estimated Departure city city of delivery Region delivery delivery time Moscow Ababurovo Moscow 655 1 Moscow Abaza The Republic of Khakassia 1401 6 Moscow Abakan The Republic of Khakassia 722 2 Moscow Abbakumova Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Abdrakhmanovo Republic of Tatarstan 682 on request Moscow Abdreevo Ulyanovsk region 1360 5 Moscow Abdulov Ulyanovsk region 1360 5 Moscow Abinsk Krasnodar region 682 3 Moscow Abramovka Ulyanovsk region 1360 5 Moscow Abramovskikh Sverdlovsk region 1360 1 Moscow Abramtsevo Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Abramtzevo (Dmitrovsky reg) Moscow region 1360 3 Moscow Abrau Durso Krasnodar region 682 1 Moscow Avvakumova Tver region 655 5 Moscow Avdotyino Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Avdotyino (Stupinsky reg) Moscow region 1360 1 Averkieva Moscow Moscow region 1360 2 (Pavlovsky Posadskiy reg) Aviation workers Moscow Moscow region 1360 1 (Odintsovskiy-one) Moscow aviators Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Aviation Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Aviation Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Motorist Arhangelsk region 655 1 Moscow avtopoligone Moscow region 1360 3 Moscow Autoroute Moscow region 655 1 Moscow agarin Moscow region 655 1 Moscow Agarin (Stupinsky reg) Moscow region 1360 1 Moscow Agafonov Moscow region 655 1 Moscow AGAFONOVA (Odintsovskiy-one) Moscow region 1360 1 Moscow Agashkino Moscow region 655 5 Moscow Ageevka Oryol Region 655 1 Moscow Agidel Republic of Bashkortostan 1360 3 Moscow Agha Krasnodar region 682 3 Moscow Agrarnik Tver region 1306 6 Moscow agricultural Republic of Crimea 682 4 Moscow agrogorodok Moscow region -

Download This Article in PDF Format

E3S Web of Conferences 266, 08011 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202126608011 TOPICAL ISSUES 2021 Ensuring environmental safety of the Baltic Sea basin E.E. Smirnova, L.D. Tokareva Department of Technosphere Safety, St. Petersburg State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering, St. Petersburg, Russia Abstract:The Baltic Sea is not only important for transport, but for a long time it has been supplying people with seafood. In 1998, the Government of the Russian Federation adopted Decree N 1202 “On approval of the 1992 Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Region”, according to which Russia approved the Helsinki Convention and its obligations. However, the threat of eutrophication has become urgent for the Baltic Sea basin and Northwest region due to the increased concentration of phosphorus and nitrogen in wastewater. This article studies the methods of dephosphation of wastewater using industrial waste. 1 Introduction The main topic of the article is to show the possibility of using industrial waste as reagents to optimize the water treatment system of rivers flowing into the Baltic Sea and water reservoirs of the Northwest-region (including part of the water system of the Vologda Region associated with the Baltic basin) in order to bring the quality of wastewater to the international requirements established for the Baltic Sea. These measures will help to improve the environmental situation in the sphere of waste processing and thereby ensure an acceptable degree of trophicity of the reservoirs. As far as self-purification processes in rivers and seas cannot provide complete recovery from wastewater pollution, the problem of removing phosphorus-containing compounds from wastewater and purifying wastewater is of great importance [1-3]. -

Combined Dendrochronological and Radiocarbon Dating of Three Russian Icons from the 15Th–17Th Century

G Model DENDRO-25341; No. of Pages 9 ARTICLE IN PRESS Dendrochronologia xxx (2015) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Dendrochronologia journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dendro Combined dendrochronological and radiocarbon dating of three Russian icons from the 15th–17th century a,∗ a b,c Vladimir Matskovsky , Andrey Dolgikh , Konstantin Voronin a Institute of Geography RAS, 119017, Staromonetniy pereulok 29, Moscow, Russia b Institute of Archaeology RAS, 117036, Dmitryɑ Ulyanovɑ st. 19, Moscow, Russia c Stolichnoe Archaeological Bureau, 119121, Iljinka st. 4, office 226, Moscow, Russia a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Dendrochronology is usually the only method of precise dating of unsigned art objects made on or of Received 10 June 2015 wood. It has a long history of application in Europe, however in Russia such an approach is still at an Received in revised form 9 October 2015 infant stage, despite its cultural importance. Here we present the results of dendrochronological and Accepted 12 October 2015 radiocarbon accelerated mass spectrometry (AMS) dating of three medieval icons from the 15th–17th Available online xxx century that originate from the North of European Russia and are painted on wooden panels made from Scots pines. For each icon the wooden panels were dendrochronologically studied and five to six AMS Keywords: dates were made. Two icons were successfully dendro-dated whereas one failed to be reliably cross-dated Icons Wiggle-matching with the existing master tree-ring chronologies, but was dated by radiocarbon wiggle-matching.