2 Van Der Tuuk's Collection of Batak Manuscripts in Leiden University Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:2011.02128V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Nov 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4203/arxiv-2011-02128v1-cs-cl-4-nov-2020-234203.webp)

Arxiv:2011.02128V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Nov 2020

Cross-Lingual Machine Speech Chain for Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, and Bataks Speech Recognition and Synthesis Sashi Novitasari1, Andros Tjandra1, Sakriani Sakti1;2, Satoshi Nakamura1;2 1Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Japan 2RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project AIP, Japan fsashi.novitasari.si3, tjandra.ai6, ssakti,[email protected] Abstract Even though over seven hundred ethnic languages are spoken in Indonesia, the available technology remains limited that could support communication within indigenous communities as well as with people outside the villages. As a result, indigenous communities still face isolation due to cultural barriers; languages continue to disappear. To accelerate communication, speech-to-speech translation (S2ST) technology is one approach that can overcome language barriers. However, S2ST systems require machine translation (MT), speech recognition (ASR), and synthesis (TTS) that rely heavily on supervised training and a broad set of language resources that can be difficult to collect from ethnic communities. Recently, a machine speech chain mechanism was proposed to enable ASR and TTS to assist each other in semi-supervised learning. The framework was initially implemented only for monolingual languages. In this study, we focus on developing speech recognition and synthesis for these Indonesian ethnic languages: Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, and Bataks. We first separately train ASR and TTS of standard Indonesian in supervised training. We then develop ASR and TTS of ethnic languages by utilizing Indonesian ASR and TTS in a cross-lingual machine speech chain framework with only text or only speech data removing the need for paired speech-text data of those ethnic languages. Keywords: Indonesian ethnic languages, cross-lingual approach, machine speech chain, speech recognition and synthesis. -

The Structure of the Toba Batak Conversation Hilman

Singapore THE STRUCTURE OF THE TOBA BATAK CONVERSATIONS Hilman Pardede, Padang Sidempuan, May 25, 1960. He graduated from PressInternational English Program of North Sumatera THE STRUCTURE University in 1987. In the year of 1992 he took Magister Program in IKIP Malang, OF THE TOBA BATAK then he went to Doctoral Program in linguistics at North Sumatera University CONVERSATION in the year of 2007. In 2008, he attended a Sandwich Program in Aurbun THEBATAK CONVERSATION TOBA OF University, Alabama, USA. In 2010, he was a speaker in the International Seminar in Trang, Thailand. He presented a paper entitled “Adjecancy Pair in Toba STRUCTURE THE Batak”. HILMAN PARDEDE This book is about the structure of the Toba Batak Conversations. The structures are categorized as interaction and linguistics. The interaction structures are restricted to adjacency pairs and turn-taking, and the linguistic structure to phonological, grammatical and semantic completion point. There are some negative cases in the structure of Toba Batak conversations. These negative cases result from the Conversation HILMAN PARDEDE Analysis (CA) as a tool used to explain the interaction and linguistic structure in Toba Batak phenomena. ISBN: Singapore International Presss Singapore International Press 2012 THE STRUCTURE OF THE TOBA BATAK CONVERSATIONS Hilman Pardede Singapore International Press 2012 THE STRUCTURE OF THE TOBA BATAK CONVERSATIONS By Hilman Pardede, Ph.D A Lecturer in English Language Teaching for Universitas HKBP Nommensen Pematangsiantar – Medan, Indonesia @Hilman Pardede, Ph.D ISBN: First Edition 2012 Singapore Do not circulate this book or any part of it in any binding or form by means of any equipment without any legal permission from Hilman Pardede, Ph.D! Prodeo et Patricia 2 For Lissa Donna Manurung and Claudia Benedita Pardede 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my deep gratitude to all those who lent their assistance and advice in the preparation and publication of this book. -

Problematic Approach to English Learning and Teaching: a Case in Indonesia

English Language Teaching; Vol. 8, No. 3; 2015 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Problematic Approach to English Learning and Teaching: A Case in Indonesia Himpun Panggabean1 1 Universitas Methodist Indonesia, Medan, Indonesia Correspondence: Himpun Panggabean, Universitas Methodist Indonesia, Medan, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 29, 2014 Accepted: November 30, 2014 Online Published: February 13, 2015 doi:10.5539/elt.v8n3p35 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n3p35 Abstract This article deals with problematic approach to English learning and teaching due to misleading conception on the nature of English and on the process of acquiring it as well as the clues to the issues. The clues are: Firstly, English is not more difficult than any other languages, including Indonesian language, Bahasa Indonesia (Note 1). Secondly, there are two approaches that need considering in English instruction, grammar free and strict grammar approaches. The former is highly recommended for early age instruction and beginners whereas the latter is recommended for instruction for specific purposes. However the two approaches should collaborate and their applications should be based on needs analysis. Thirdly, Conflicting conception on whether L1 and L2 are the same processes should not deter the strategy of how language is acquired naturally. When proper conception on the nature of English is attained and it is approached properly, English subject is not burdensome and needs not be eliminated from Primary School curriculum, and there is no need to reduce time allotment for the subject in Senior High School as stipulated in Indonesian English curriculum amendment. -

World Directory of Minorities

World Directory of Minorities Asia and Oceania MRG Directory –> Indonesia –> Batak Print Page Close Window Batak Profile The 6 million or so Bataks (Indonesia Census, 2000) belong to one of about seven ethnic groups (Alas- Kluet, Angkola, Dairi, Karo, Mandailing, Simalungun and Toba) inhabiting the interior of Sumatera Utara Province south of Aceh. Their languages are within their own branch of Sumatran languages, part of the Austronesian family, and most of them live in the highlands, especially around Lake Toba, to the west of Medan. Mainly Christians (though a small percentage are Muslim), the Batak are organized along patriarchal group lines known as marga. This group owns land and does not permit marriage within it. The marga has proved to be a flexible social unit. Batak who resettle in urban areas, such as Medan and Jakarta, draw on marga affiliations for financial support and political alliances, reinforcing their ethnic identity. Historical context Indigenous minorities who have long inhabited the highlands of north-central Sumatra, the Bataks have lived in relative geographic isolation throughout much of history, though there are historical references to them going back to the thirteenth century. Their fighting traditions, and their reputation as cannibals, probably also helped to reinforce their relative isolation. This began to change in earnest at the start of the nineteenth century when the Bataks and the neighbouring Minangkabau minority – already Islamized – were involved in a series of conflicts. Some Bataks, such as the Mandailing, Angkola and Karo, began to convert, often then calling themselves Malay. The Dutch themselves were relatively late arrivals here, with the first Dutch missionaries only being sent from 1850, and the Bataks themselves only being completely subdued after what is sometimes referred to as the Batak war of 1872–94. -

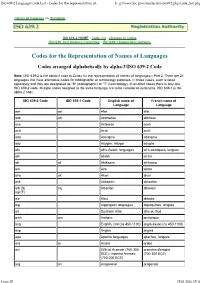

ISO 639-2 Language Code Lis

ISO 639-2 Language Code List - Codes for the representation of... h p://www.loc.gov/standards/iso639-2/php/code_list.php Library of Congress >> Standards IS0 639-2 HOME - Code List - Changes to Codes ISO 639 Joint Advisory Committee - ISO 639-1 Registration Authority Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages Codes arranged alphabetically by alpha-3/ISO 639-2 Code Note: ISO 639-2 is the alpha-3 code in Codes for the representation of names of languages-- Part 2. There are 21 languages that have alternative codes for bibliographic or terminology purposes. In those cases, each is listed separately and they are designated as "B" (bibliographic) or "T" (terminology). In all other cases there is only one ISO 639-2 code. Multiple codes assigned to the same language are to be considered synonyms. ISO 639-1 is the alpha-2 code. ISO 639-2 Code ISO 639-1 Code English name of French name of Language Language aar aa Afar afar abk ab Abkhazian abkhaze ace Achinese aceh ach Acoli acoli ada Adangme adangme ady Adyghe; Adygei adyghé afa Afro-Asiatic languages afro-asiatiques, langues afh Afrihili afrihili afr af Afrikaans afrikaans ain Ainu aïnou aka ak Akan akan akk Akkadian akkadien alb (B) sq Albanian albanais sqi (T) ale Aleut aléoute alg Algonquian languages algonquines, langues alt Southern Altai altai du Sud amh am Amharic amharique ang English, Old (ca.450-1100) anglo-saxon (ca.450-1100) anp Angika angika apa Apache languages apaches, langues ara ar Arabic arabe arc Official Aramaic (700-300 araméen d'empire BCE); Imperial Aramaic (700-300 BCE) (700-300 BCE) arg an Aragonese aragonais 1 von 15 15.01.2010 15:16 ISO 639-2 Language Code List - Codes for the representation of.. -

Me and Toba a Childhood World in a Batak Memoir*

ME AND TOBA A CHILDHOOD WORLD IN A BATAK MEMOIR* Susan Rodgers In many ethnic cultures in Indonesia the time spent growing up is often thought of as a period when individuals move beyond a supposedly incomplete, not fully human state of infancy toward a more orderly time of "truly human" adulthood. Babies are typically viewed as considerably less than full persons, and childhood is the time they become completely human: through learning the adat ("local custom"), by coming to discern and interact appropriately with the various types of kinspeople and social classes around them, and— perhaps most centrally— by learning to speak the local language. A writer’s memoirs of his childhood often subtly detail this fundamental process of becoming human while recording the more mundane experiences of growing up. Given this framework, autobiographical accounts in Indonesia often bear on much larger cultural issues. For youngsters in late colonial times growing up also often meant "becoming a Javanese" or "becoming a Toba Batak" or whatever the local society happened to be. In accord with this, young children were not really full Javanese or Toba, although they lived in those societies. They were joined in this unfinished state by foreigners, the insane, and those outside adat and local speech conventions. A proper childhood worked as a door into full Javanese—ness or Toba-ness. Childhood memoirs often narrate an author’s passage through such a transition. Dr. H. Ruslan Abdulgani, formerly minister of information and minister of foreign affairs as well as Indonesia’s ambassador to the UN, includes a passage in his auto biography that expertly weaves together all these themes of maturation, personhood, speech, etiquette, and ethnic "completeness." The first chapter of Ms autobiography is entitled "My Childhood World"* 1 and portrays the bustling, socially variegated kampung (neighborhood, in this case) called Plampitan in Surabaya where Ms family lived. -

INDO 93 0 1337870193 1 32.Pdf (802.5Kb)

How I Learned Batak: Studying the Angkola Batak Language in 1970s New O rder Indonesia Susan Rodgers1 How were "local languages" and "local cultures" constituted during the New Order? How was the visiting anthropologist construed during the Soeharto regime? How were anthropology and "culture" itself imagined in New Order times by diverse parties engaged in these profoundly politicized (if veiled) narrative discourses? John Pemberton's findings about New Order cultural imaginaries set out in his On the Subject of "Java"2 provide macro-level insight and excellent historical grounding for beginning to answer these questions, as Pemberton focuses on constructions of so- called traditions revolving around the royal court of Surakarta. This present essay offers an autobiographical, experiential parallel to Pemberton's work by setting out my memories of working with a seventy-six-year-old retired schoolteacher who taught me the Angkola Batak language in 1974 as part of my first term of fieldwork in Sipirok, South Tapanuli, North Sumatra. My teacher's pedagogies and language ideology were shaped by Dutch colonial visions of language and learning; his way of presenting his home language to me as a brilliant, civilizing gift was also animated by his discomfort and skepticism with the New Order government's negative stereotypes about so-called 1 Indonesian language and literature specialist Professor Sylvia Tiwon of the University of California- Berkeley first suggested to me that I write about my Batak language learning experiences. Without her suggestion, I would not have launched into this essay. English professor Helen Whall of Holy Cross gave early drafts a careful reading, for which I am deeply grateful. -

Language Contact, Maintenance and Loss: a Sociolinguistic Study on Linguistic Consequences of Ethnicity and Nationalism in Indonesia

LANGUAGE CONTACT, MAINTENANCE AND LOSS: A SOCIOLINGUISTIC STUDY ON LINGUISTIC CONSEQUENCES OF ETHNICITY AND NATIONALISM IN INDONESIA THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF IN LINGUISTICS %^ By RAHMADSYAH RANGKUTI Enrolment No. Z-4751 Under the Supervision of Prof. S. Imtiaz Hasnain T DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2005 ^,aO^ */«.«/,^ T6712 Dr. S. IMTIAZ HASNAIN /fe^V Department Of Linguistics (Professor) rY^rT^l^l Aligarh Muslim University .; Aligarh 202002 INDIA Dated:A3/p//o5: C^^RTITICAT^ I hereby certify that the thesis entitled "Language Contact, Maintenance and Loss: A Sociolinguistic Study on Linguistic Consequences of Ethnicity and Nationalism in Indonesia" submitted by Mr. Rahmadsyah Rangkuti for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics has been completed under my supervision. It is further certified that the thesis submitted by him is his original work and to the best of my knowledge this work has not been submitted earlier anywhere. Prof. S. Imtiaz Hasnain Supervisor ACKNOWLEDGMENT Honestly speaking, the work on the present study could not have been undertaken and completed without the help, guidance, supervision and support of a number of people, and therefore I wish to express my appreciation and gratitude to all of them. First, I would like to express my special gratitude to my supervisor Dr. S. Imtiaz Hasnain, Professor in Sociolinguistics, Department of Linguistics, Aligarh Muslim University, for the guidance, supervision and fatherly advice during writing of this study. My gratitude is also extended to Prof. Mirza Khalil Beg, Chairman of Department of Linguistics, AMU, and Prof. A. -

U. Kozok on Writing the Not-To-Be-Read; Literature and Literacy in a Pre-Colonial Tribal Society

U. Kozok On writing the not-to-be-read; Literature and literacy in a pre-colonial tribal society In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 156 (2000), no: 1, Leiden, 33-55 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 11:05:45AM via free access ULI KOZOK On Writing the Not-To-Be-Read Literature and Literacy in a Pre-Colonial 'Tribal' Society Introduction To date, there have been no attempts to define the significance, function and spread of literacy in Batak society, nor any study that places the Batak case in a wider Indonesian or Southeast Asian perspective. This article is intended as an attempt to fill in this obvious gap in current scholarship, drawing mainly on two sources: data from the 1920 and 1930 colonial censuses, and informa- tion from the Batak manuscript tradition. The different Batak ethnic groups are distinguished not only culturally but also linguistically. All six Batak groups belong to a single language group, which can be divided into at least two subgroups of mutually unin- telligible languages. The closely related languages of the Mandailing, Angkóla, and Toba represent the southern subgroup, while the languages of the Karo, Pakpak and the small non-Batak people of Alas (Southeast Aceh) represent the northern group. The language of the Simalungun, though often regarded as a subgroup by itself, is obviously an earlier offspring of the southern branch of the Batak languages (Adelaar 1981). Prior to the arrival of the German Mission and the Dutch Colonial Government in the second half of the nineteenth century and the early twen- tieth century, the Batak, especially the two larger ethnic groups, the Toba and the Karo, with which this article is mainly concerned, were a tribal society, bound together by kinship ties and lacking a marked social stratification. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright A GRAMMAR OF NIAS SELATAN Lea Brown A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of University of Sydney 2001 Except where otherwise acknowledged, this thesis represents the original research of the author Lea Brown (Pamela Leanne Brown) University of Sydney 2001 ______________________ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A funny thing happened on my way from doing my B.A. at Melbourne Uni to the rest of my life: I went to a seminar given by Bill Foley in which he described some of his adventures during field work in PNG. -

Reconstructionand Sub-Grouping of Batak Languages

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 18, Issue 6 (Nov. - Dec. 2013), PP 35-55 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Reconstructionand Sub-grouping of Batak Languages Himpun Panggabean1, Robert Sibarani2, Dwi Widayati3, Namsyah Hot Hasibuan4 1Universitas Methodist Indonesia, Medan, Indonesia, 2Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia,3Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia, 4Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia Abstract:This article contains a report of research into reconstruction and sub-grouping of Batak languages (BLs) composed of Toba language (TL), Simalungun language (SL), Pakpak Dairi language (PDL), Angkola language (AL), Karo language (KL), and Mandailing language (ML) spoken in North Sumatera, Indonesia.The research problems cover the sound correspondences, proto-phonemes, and sub-grouping of BLs. The data are the utterances of the native speakers of BLsbeing recorded in IPA Kiel transcription and are analysed with comparative method. The analysis shows that sound correspondence sets in BLs are of two types, namely the sets resulted from linear inheritance and the setsfrom sound innovation.Based on the correspondence sets, proto-phonemes are reconstructed and BLs are sub-grouped.The analysis also shows that BLs can be classified into three sub-groups, namely TL-AL-ML, PDL-KL, and SL. Keywords: Batak languages, sound correspondences, proto-phonemes, reconstruction, sub-grouping. I. Introduction Languages keep changing. The changes of languages occur regularly and recognizably and can be seen in genetically related languages called sister languages. Schleicher (1871) in McManiset al. (1987:265) proposed the Family Tree Theory assuming that languages change in regular, recognizable ways (the Regularity Hypothesis) and that because of this, similarities between languages are due to genetic relationship between those languages (the Relatedness Hypothesis). -

The Development and Challenges of Indonesian Language As an Academic Language

THE DEVELOPMENT AND CHALLENGES OF INDONESIAN LANGUAGE AS AN ACADEMIC LANGUAGE Burhanuddin Arafah Faculty of Letters Hasanuddin University, Indonesia E-mail Address: [email protected] Abstract This paper discusses two major issues, i.e. the development of Indonesian language or Bahasa Indonesia (BI) and the challenges faced by BI to be an academic language as a means for developing science and enhancing the intellectuality of Indonesian people. BI symbolizes the culture of nation which has an extraordinary historical development. BI had been used as a lingua franca known as the Malay language since the period of Srivijayan Empire. BI grew and developed as a language of struggle in the colonial period and used to unify the archipelago’s diverse ethnic, cultural, and language groups into one nation. BI was then elevated to the status of official language based on the 1945 Cconstitution. Then, a number of agencies (e.g. the language center) were formed to deal with language planning with responsibilities for standardisation and modernisation of BI in order to satisfy all communication purposes including scientific communication of academic community. However, the effort to place BI as a modern and prestigious academic language is hindered by negative attitudes of Indonesian people and competition with foreign languages that have positioned BI to survive or to be ignored. Therefore, this situation requires a serious thought and an effective action to elevate the status of BI to be a reliable language for scientific and academic usage. This is possible to do when all level of educational institutions, as the agent of science and technology development, would like to change their perception that mastering a foreign language, especially English is the only way to get the access to the development of science and technology since all important resorces of science are in English.